A few years ago, a Clint character, Robert Kincaid, wandered Madison County, Iowa for National Geographic, shooting rustic bridges for a feature article, and met lonely housewife Meryl Streep in the movie adapted from the Robert James Waller weepie The Bridges of Madison County. Acknowledging that your webmaster is more likely to encounter muggers than Meryl in Central Park, FNY has endeavored to capture the nearly 40 ornate bridges that sprang from Olmsted and Vaux’ genius when building Central Park nearly 150 years ago.

When you wander Central Park, the first thing you have to remember is that no matter how ‘natural’ it looks, it’s an entirely artificial construction and that nothing has been left to chance by its builders, Calvert Vaux and Frederick Law Olmsted. The pair won a competition to design a large park in Manhattan with their “Greensward” design in 1858. The land for Central Park had already been bought by 1853.

The design called for three specific types of roadways for the park: footpaths, carriageways, and bridle paths, and to make traffic that much easier and to eliminate any awkward congress among the three, a series of bridges and arches were planned. At first only seven bridges, two tunnels and masonry bridges and a footbridge were to be built. That number eventually swelled to nearly 40 arches and bridges.

In an age when architects were sure to make their creations as ornate and conspicuous as possible, Olmsted and Vaux seemed to make certain that their Central Park bridges and arches were treasures to be sought out and savored once they were found. They always seem to be around a bend or hidden behind the trees–until the moment when you stumble on them, and then you are rewarded with some of the most unostentatious yet subtly magnificent views the park has to offer.

The bridges and arches of Central Park pretty much fall into two classes: bridges made from brick, stone or rock, and castiron bridges. Calvert Vaux did the bulk of the bridge designs, with assistance from architect Jacob Wrey Mould on the castiron bridges, which are the oldest such bridges in America.

Part 1: South of the Reservoir

To enable Forgotten Fans to visit all the Central Park bridges, which should take three to four hours of walking, we’ll start with the bridges near the Metropolitan Museum at 5th Avenue and 80th Street, travel south, west, north with a few detours, then east and then northwest again, finishing up at 110th Street and Central Park West. I’ll use the Central Park Reservoir as a dividing line. We will do those arches north of the Reservoir in Part Two.

Recommended: a good map of Central Park, which can be found in the Barnes & Noble Complete Illustrated Map and Guidebook to Central Park. Few guides, though, show all the bridges; the only one I know about is the hard-to-find Bridges of Central Park by Henry Hope Reed, Robert McGee and Esther Mipaas, as part of the Arcadia Images of America series.

Shall we go?…

![]()

Location: under West Drive, south of The Obelisk and west of Metropolitan Museum. Built: 1861-1863 by Vaux and Mould

Greywacke Arch is the only arch in Central Park that is named for the material with which it is built. “Greywacke” is a variety of sandstone obtained from the Hudson River Valley.

| Detail of the trefoil design that distinguishes the stone work on Greywacke Arch. |

The pointed arch is called “Saracenic”, which is a horseshoe arch pointed at the top. Some Spanish and Middle Eastern architecture takes this form.

Like many Central Park arches, it had fallen into disrepair; it was restored from 1983-85.

![]()

Location: along park path just west of 5th Avenue and 79th Street. Built: 1862 by Vaux

Constructed of New Brunswick sandstone, Glade Arch is another of Calvert Vaux’ older central Park bridges. It suffered rather more deterioration over the years from tree roots, crumbling and graffitists. Finally, after a large part of the balustrades (fence posts) were wiped out by a snow plow in 1980, a complete renovation was completed the next year.

The abutments on either side of Glade Arch feature sunken quatrefoils (four-lobed decorations)

From Glade Arch take the path that forks off to the right that leads to the Boathouse and Central Park Lake. You will soon be in sight of…

![]()

Location: along park path under East Drive near the Boathouse and Central Park Lake. Built: 1862 by Vaux and Mould

In architectural lingo, “trefoil” means a design featuring 3 lobes, like a shamrock. Consequently, ‘quatrefoil’ and ‘cinquefoil’ mean designs featuring 4 and 5 lobes.

It’s easy to see, then, how Trefoil Arch got its name. It also features quatrefoil designs flanking the arch.

Trefoil Arch has the distinction of being the only archway in Central Park featuring a different design on each side.

The “western” side of Trefoil closest to the Lake has a round archway instead of a trefoil, and plain voussoirs (blocks that make up the arch) instead of the floral patterns found in the “eastern” trefoiled side.

Scenes from the Jack Lemmon classic “The Out Of Towners,” one of the most anti-New York movies ever made, were filmed at Trefoil.

Continue along the path close to the Lake and you will soon see the massive Bethesda Fountain, which is fronted by the largest and grandest of all Central Park arches…

![]()

Location: north end of the Mall in front of Bethesda Fountain and Central Park Lake, carries Terrace Drive connecting East and West Drives. Built: 1859 -1863 by Vaux and Mould. Made mostly of sandstone and granite.

Calvert Vaux was, according to legend, inspired by the Orangerie at the Palace of Versailles in Paris because the designs of both spaces are similar.

Hidden under the arches are colorful tiles on the ceiling made by the Minton Company of Stoke-on-Trent, England. Many of them have been removed for restoration.

By the 1970s, Bethesda Terrace was severely deteriorated but careful work has gradually restored it to its old glory.

Stairway on west side of Terrace Bridge

Though Versailles may have been its inspiration, the real genius of the Terrace Bridge lies in its detail work, executed by Jacob Wrey Mould. A flamboyant personage, he was disliked by many of his contemporaries, but he brought a whimsical personality to much of his work. Nowhere is this more in evidence in Central Park than in these stone carvings that line the grand staircases that descend to the fountain.

Carvings depicting nature, farming, and the seasons, executed in the mid-19th Century, show how much New York City of that time was still very mindful of agriculture and the land. There were still many farms on Manhattan itself in the mid-19th Century; Central Park’s Sheep Meadow had sheep.

Mould may have been a bird fancier since so many of the reliefs are of avian subjects. Fish and game appear as well. Even beekeepers aren’t left out.

Reflecting how much religion played a part of life in those days, a Bible and a lamp are shown. A relief depicting harvest time shows a grinning jack o’lantern.

Mould’s decorative designs can’t go unmentioned either; although they aren’t representative of game, fish or fowl they look alive, just the same.

For our next bridge, walk along the Lake northeast of Bethesda Terrace….

![]()

Location: spans the Lake northeast of Bethesda Terrace. Built: 1859 -1862 by Vaux and Mould, with ironwork by Janes, Kirtland & Co. (which also did the ironwork for Washington’s Capitol Building). Made of cast iron.

Bow Bridge was one of the seven original cast iron bridges built in Central Park during the years 1859-1875. Two of the originals were destroyed when Robert Moses became Parks Commissioner: Spur Rock Arch and Outset Arch, which took Center Drive over the bridle path, fell victim to auto traffic priorities (which, as we know, always takes priority in NYC).

Bow Bridge, having fallen into disrepair, was renovated in 1974 and again in 1998.

You can’t see them, but cannonballs are set in the base of the north end of the bridge to allow expansion during temperature changes.

Nellie, the dog, would like to decorate one of Bow Bridge’s balustrades. She didn’t. The railing features Gothic cinquefoils and interlaced spiral designs. Large vases originally decorated the balustrades.

Bow Bridge has appeared in many movies and TV shows, such as 1966’s Blindfold with Rock Hudson and Claudia Cardinale.

Double back from Bow Bridge, cross in front of Bethesda Terrace and proceed south on The Mall. At the statue of FitzGreene Halleck, turn left and follow the park path. You will soon reach…

![]()

Location: takes East Drive over park path east of the Mall west of about 67th Street. Built: 1861 by Vaux and Mould, with iron railing by J.B. & W.W. Cornell Iron Works. Made of sandstone and brick.

Some of the blocks on the arch, including the keystone, are vermiculated–they have designs cut in them resembling worm tracks.

Through the arch is a statue of Balto, the lead sled dog who transported diphtheria serum across Alaska in the winter of 1925.

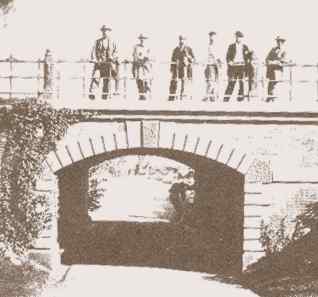

Architects of Central Park stand on Willowdell Arch, 1862. Calvert Vaux is third from left, while Frederick Law Olmsted is on the right and Jacob Wrey Mould is second from right.

A left turn along a park path after crossing the transverse road leads you to…

![]()

Location: supports the 65th Street Transverse Road near 5th Avenue and the Central Park Zoo. Built: 1859-1860 by Vaux. Made of pale olive New Brunswick sandstone.

Denesmouth Arch has quatrefoil designs on the balustrades. It used to feature four ornate castiron lampposts, three of which were stolen; the 4th is in safekeeping somewhere. The arch is located near The Dene, a knoll between 5th Avenue and East Drive above 65th Street. It is the only Central Park arch made completely of sandstone.

Nearby, don’t miss the Delacorte Musical Clock Tower, featuring a bronze menagerie that plays a tune every half hour.

Return to East Drive and walk toward Grand Army Plaza…

![]()

Guard shoos people away as work proceeds under Greengap in summer 2001.

Location: supports East Drive over a walkway between the Zoo and Wollman Rink. Built: 1861 by Vaux and Mould.

Originally, Greengap Arch took the drive over a bridle path leading to Scholars Gate at Grand Army Plaza.

In 2001, the path under Greengap Arch was closed due to reconstruction of the area surrounding Central Park Pond.

Original detail on the balustrade posts has survived.

A few yards south on East Drive can be found…

![]()

Location: takes East Drive over park path near The Pond. Built: 1873 by Vaux. Made of granite.

Inscope Arch is actually one of the “newer” arches in Central Park. It was built a good ten years after most of the other ones!

The archway is Tuscan, i.e. the outside arch comes to a point at the top, and is round at the bottom.

Inscope has a considerable foundation because it was built on a swamp. It has timber sub-flooring.

Walk on the path under Inscope and continue on for a few yards.

![]()

Location: takes park path over The Pond.. Built: 1896 by Howard & Caudwell. Made of Manhattan schist.

Overlooks, on the west, Hallett Nature Sanctuary and the north, Wollman Rink, and has always been a favorite spot for photographers. The present Gapstow replaced the original wood and cast iron structure built by Vaux in 1874.

The Plaza Hotel, at right, is featured in this view from Gapstow Bridge

On East Drive, reverse your course and take a park path through the Dairy (which at one time did indeed dispense fresh milk to city kids at a time when not all milk was pasteurized). Directly ahead you will see…

![]()

Location: takes park path under Center Drive leading to The Carousel. Built: 1861 by Vaux and Mould. Made of pressed brick with granite trim.

Location: takes park path under Center Drive leading to The Carousel. Built: 1861 by Vaux and Mould. Made of pressed brick with granite trim.

Playmates Arch, along with the Dairy, the Carousel, the Zoo and the Chess & Checkers House, is in a part of Central Park once formally designated as the Children’s District. Its distinctive yellow and red bricks and beige voussoir blocks gave it the nickname “tri-colored arch.”

Playmates Arch has one side of its original railing remaining; the other side is a reasonable facsimile from 1989.

Walk south along Center Drive and soon you will reach…

![]()

Location: takes Center Drive over park path at about 63rd Street. Built: 1860 by Vaux and Mould. Made of red brick and New England sandstone.

The path under Driprock Arch used to be a bridle path.

An osage orange tree, rare in the Northeast U.S., can be seen near the arch.

As you continue south on Center Drive, follow it to the right, as it curves around Central Park’s southern edge. At Seventh Avenue you will arrive at…

![]()

Location: takes Center Drive over park path leading to Artisan’s Gate at 7th Avenue. Built:1862 by Vaux and Mould. Made of granite (from a quarry in Seal Harbor, Maine) and red brick.

Dipway Arch is rather important in that it allows pedestrians to bypass Center Drive, which is busy with cars during the week.

Dipway’s granite has a distinctive two-tone bluish color that’s offset by its red brick underpass. Its original cast-iron railings are intact. Like many Central Park arches, the underpass gets waterlogged after a rain.

The underpass used to feature benches, but these are long gone.

A cast iron bridge, Spur Rock Arch, was formerly along the path directly through Driprock, but it was destroyed by Robert Moses in 1938 so Heckscher Playground could be expanded.

After sojourning at Driprock, continue along Center Drive. As it makes a turn north (and you ease off to the right) it turns into West Drive. Just past Columbus Circle, you will see…

![]()

Location: takes West Drive over park path just east of 61st Street.Built: 1860-1862 by Vaux. Made of gneiss and New England sandstone.

Greyshot Arch (not to be confused with Greywacke Arch, above) was an early Calvert Vaux design.

Greyshot features distinctive styled fleurs-de-lis on the balustrades (fencing).

Do not return immediately to West Drive … continue along the path beneath Greyshot Arch because you have a treat in store for you.

![]()

Location: takes park path over bridle path near Heckscher Playground. Built: 1861 by J.B. and W.W. Cornell Ironworks. Made of cast iron, steel and wood.

One of Central Park’s few remaining cast iron bridges, Pine Bank Arch (its official name, though it’s more properly a bridge) was in dire straits by 1984, so rusty it was about to crumble. That’s when a costly and painstaking restoration was mounted. Parts that had fallen off had to be fabricated, old paint and rust had to be scraped off and the old concrete deck replaced with a wooden walkway. The result is one of Central Park’s true drawing cards, if you’re an ornamental bridge fan.

Greyshot Arch can be seen from Pine Bank. This is the closest that two Central Park bridges or arches approach each other.

Walk along the bridle path under Pine Bank Arch, and as you again approach West Drive, you will arrive at…

![]()

Location: takes West Drive over bridle path near West 64th St. Built: 1860-1862 by Vaux. Made of sandstone and brownstone.

Featuring quatrefoil cutouts on the balustrades, Dalehead looks much the way it did when first opened over 140 years ago.

The east and south parts of Central Park were the first to be opened, and they are also the parts of the park where bridges and arches are most numerous. From here on out, there’s quite a bit of space between bridges.

Our next arch lies about eight blocks to the north. Follow West Drive to 72nd Street…

![]()

Location: takes 72nd Street over bridle path to west Drive near Strawberry Fields. Built: 1862 by Vaux. Made of Manhattan schist.

One of Central Park’s “natural” arches. Calvert Vaux’ aim was to build a natural-setting bridge instead of one using brick and mortar. The bridge has brick supports, but these are concealed by boulders, shrubs and trees.

Riftstone is one of the least-seen arches in the park, since most pedestrian and auto traffic crosses on it on 72nd Street on its way into the park. The bridle path beneath it is relatively bereft of equines…er, there’s not many riders on it, so not many know about it.

Follow the bridle path five blocks north and at 77th Street you will see…

![]()

Location: takes 77th Street over bridle path to West Drive at Naturalists’ Gate. Built: 1890; architect: Josiah Cleveland Cady. Made of gneiss.

Though it is over 110 years old, Eaglevale Bridge is actually one of the newer arches in Central Park. It carries the 77th Street access road over the bridle path and what was once Ladies’ Pond (reserved for ladies-only ice skating in the 1890s. Why ladies only? To put skates on, women had to expose their ankles and Peeping Toms abounded), before Robert Moses filled it in in 1936 and replaced it with a playground. Even today, the water, which lurks underground, floods the area after a heavy rain.

Near the Central Park Lake you will find three bridges close together. Follow the 77th Street access road to West Drive and continue north and you will walk on…

![]()

Location: takes West Drive over an arm of The Lake near the American Museum of Natural History. Built: 1860 by Vaux. Made of sandstone, cast stone, schist and greywacke.

Named for its two bays, or balconies, that feature seating for weary park walkers on hot days. Balcony Bridge provides one of Central Park’s most scenic views over The Lake toward Central Park South and 5th Avenue to the east. The presence of balconies on the east but not west sides makes Balcony Bridge asymmetrical, a distinction shared by only Trefoil Arch (see above).

Quatrefoil cutouts on the balconies complete the scene.

Follow the park path trailing off from the east side of West Drive toward The Lake and you will soon come upon…

![]()

Location: takes park path over an arm of The Lake, Bank Rock Bay, near the American Museum of Natural History. Built: 1860 by Vaux. Made of white oak with wooden floorboards, and steel.

Bank Rock Bridge was originally known as Oak Bridge and had cast iron balustrades and yellow pine floorboards. It was rebuilt along utilitarian lines in 1982.

In 2009 the Central Park Conservancy, using using historic photographs, archival records, and Vaux’s original drawings, rebuilt Oak/Bank Rock Bridge to close to its original appearance.

Compare it to what it looked like between 1982 and 2009:

We are now entering the Ramble, one of Central Park’s quietest, most natural spots. It isn’t natural at all; every square inch was planned by Olmsted and Vaux.

Before proceeding into the Ramble to see our next Arch, look to your left after crossing Bank Rock Bridge.

This is the first in a series of small wooden bridges placed over small streams in Central Park. It is known as Gill Bridge because it crosses the Gill, a stream trailing from The Lake. It has been destroyed by vandals a good many times through the years, but the Central Park Conservancy keeps rebuilding it. It is made of natural timber and has been given back its original contorted branches.

Don’t cross Gill Bridge, but proceed straight ahead, into the Ramble. Before you is…

![]()

Location: in the heart of The Ramble. Accessed by path leading from Bank Rock Bridge. Built: 1863 by Vaux. Made of rock-face ashlar.

Ramble Arch has the distinction of being the narrowest of Central Park’s arches, with its opening measuring only 5 feet across.

Henry Hope Reed, in Bridges of Central Park::

This rough stone structure would seem to have been inspired by some neo-classic landscape in which people dance about the ruins of antiquity overgrown with vines and grasses.

Once passing through Ramble Arch, you can either explore the shady hills and winding paths of The Ramble, including the ruins of the nearby Cave (though they are now fenced off) or backtrack onto West Drive, and proceed north about five blocks to our next Arch…

![]()

Location: takes West Drive over bridle path at about 82nd Street.Built: 1860-1861 by Vaux. Made of Maine granite and sandstone with cast iron railings.

This part of Central Park was originally landscaped to evoke winter, with evergreens planted on each side of the arch.

In the 1990s cast iron railings were installed to approximate the originals, which had been replaced with cheap metal piping and chain links.

Vault is lined with red and white brick in a cross pattern.

After leaving Winterdale Arch, we’ll take a side trip along the roadway that skirts the southern edge of the Reservoir to see two bridges that have survived decades of decay and then renewal.

Proceed along the bridle path and walk north till you get to the next Transverse drive. Then take the bridle path to the right. Before long you will reach Southwest Reservoir Arch….

… in THE BRIDGES OF CENTRAL PARK PART 2.

7/2/2001; revised 2012

8 comments

What a great guide to these beautiful bridges. I noticed a typo in Part 1. You say the Greywacke Arch goes under West Drive and it should say East Drive. Thanks for the beautiful pictures and great guide.

Question:

Where is the bridge (pedestrian tunnel) that was used in the final scene of the movie “They Might Be Giants”?

I am going to Central Park for the first time soon and would love to stand in that tunnel.

kwennerberg@gmail.com

The ending of “They Might Be Giants” was filmed on the pedestrian path leading up to Trefoil Arch. We know they’re approaching the arch from the east side, because the other side has a different design.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nse8jE_Mb8I

One of my favorite movies of all time, even though almost nobody gets it.

I am a NYC history buff with a passion of hidden gem. This is the website I was looking for. Thank you very much!

The following article suggests it refers to the Driprock bridge, of Philadelphia brick and New Brunswick sandstone:

The New York Herald, June 24, 1860, Page 5

…. We now enter the Park. The first thing we meet is a board having these words painted thereon: – “Temporary road – carriages can pass this way.” But the board was so placed that it might be difficult to tell which was the read indicated. A barricade of rails was stretched along the drive, but there seemed to be a side entrance, and a young man on horseback, thinking that must be the “temporary road,” went through there; he tried it, but found that, laving proceeded about a sixteenth of a mile, he had to turn back, aa his path was blocked up with another lot of rails. With no good grace he tried another direction, which although it led somewhat out of the way proved to be more satisfactory. The cause of the blockade of the drive is the construction of a bridge over the bridle road, running from the back of the arsenal along the edge of the lower lake, and thence onward to the other side of the Park. This bridge Is likely to be a very noble structure, and is being built of the best Philadelphia brick and New Brunswick free stone. The style of architecture is somewhat after the Italian, and the upper part will be composed of one hundred and twenty balusters, besides ornamental panel work. The arch will be twenty-five feet span by about twenty feet in height, and ono hundred and six feet from out to out. The bridge is being built by contract, by Messrs Stewart & Howell.

We got engaged on Pine Bank Bridge and I am going to name all of the tables at our wedding breakfast after the bridges of central park, This is a great guide, and just what I was looking for! Thank you!

Did I miss Gothic Bridge..?

..amazing thanks!