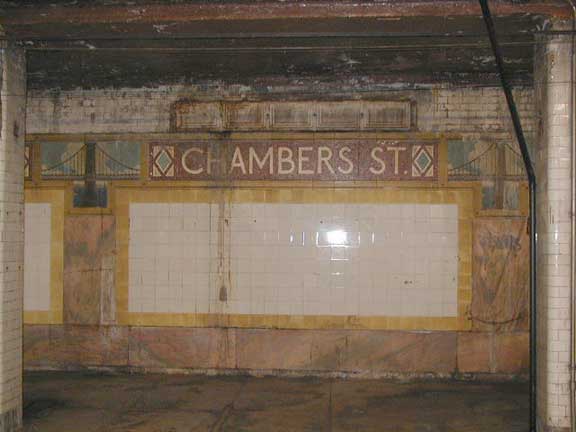

BMT Chambers Street uptown platform, November 2003

That’s harsh, but the truth hurts sometimes.

In many ways, the NYC subway system and the transportation network of which it is a part is set to make a renaissance in the next decade. A new Second Avenue Subway is supposed to break ground; expansions of the Flushing Line and Long Island Railroad are being discussed; a new “transit hub” will rise on Broadway and Fulton Street; a new Atlantic Avenue LIRR terminal is rising in Brooklyn; and there are plans to rebuild Penn Station in the Farley Post Office Building on 33rd Street between 8th and 9th Avenues. New cars have already been put into service on the BMT and LIRR, and the old R-33/36 Redbirds will be officially retired this week (November 2003). Crime and equipment breakdowns have been vastly reduced since their nadir in the 1970s. And still…

Remember the scene in Beneath The Planet of the Apes when astronaut Brent and Nova are searching for Charlton Heston? They leave Ape City, enter the Forbidden Zone, and find a wrecked Queensboro Plaza next to the New York Stock Exchange (this is the movies, remember), as well as a flock of dangerous telepathic mutants.

Remember the scene in Beneath The Planet of the Apes when astronaut Brent and Nova are searching for Charlton Heston? They leave Ape City, enter the Forbidden Zone, and find a wrecked Queensboro Plaza next to the New York Stock Exchange (this is the movies, remember), as well as a flock of dangerous telepathic mutants.

I was riveted to my seat in the now-closed Bay Ridge Harbor Theater in 1970 as Heston blew up earth in the final scene, and had marveled at the impressive, for the time, special effects in showing a destroyed NYC transit system. It was my first encounter with a cinematic dystopia (I hadn’t yet seen On the Beach, and Heston hadn’t made The Omega Man yet.) It made a real impression. You can experience the same conditions, sort of, in a busy subway station in downtown Manhattan.

It wasn’t till the 1980s when I started riding NYC subway lines that weren’t the ones I regularly rode to go to school or work. Even now, I hadn’t spent much time with the J train, which runs from Broad Street across the Willliamsburgh Bridge, down Brooklyn’s Broadway out to Jamaica in Queens. And it’s the line’s Chambers Street station, whose uptown platform is largely unchanged for at least six decades, that I still believe fervently is the true face of the NYC subway system. And don’t forget, I’m a mass transit supporter.

When the Chambers Street station was built in 1913, it served as a terminal for trains arriving from the Williamsburgh Bridge. In 1915 it started hosting trains from the Manhattan Bridge as well.

Its original name tablets (featuring the diamond motif Brooklyn Rapid Transit and later, Brooklyn-Manhattan Transit, the BMT used in station nomenclature) can still be found on the abandoned eastern platform.

The walls have pink marble accents as well as large, T-shaped plaques depicting the Brooklyn Bridge.

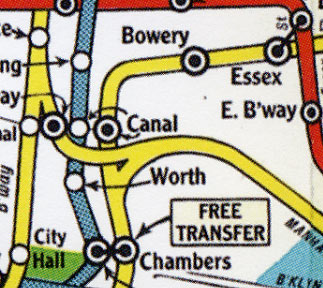

This 1956 Hagstrom subway map shows the BMT in yellow and the IRT in blue. Here you can see a depiction of the BMT turning south off the Manhattan Bridge to Chambers Street. (The IRT Lexington Avenue station Worth Street was closed in 1962.)

It’s hard to remember now, but Chambers Street actually used to handle trains coming off the Manhattan Bridge. Two tracks on the south side of the Manhattan Bridge, now used by the various lines connecting the BMT Broadway and Fourth Avenue or Brighton lines (in 2003, the N, Q, W) used to instead turn south and enter Chambers Street from the north. Sea Beach line trains ran from Chambers Street to Coney Island at first, then trains from the Brighton, 4th Avenue and West End lines.

After a new tunnel was constructed in 1967, Chambers Street service over the Manhattan Bridge was abandoned, and Sixth Avenue line service entered the Manhattan Bridge. However, tracks from Chambers Street still lead north from the station toward the bridge.

A lost chapter in the Chambers Street story is that it also served as a terminal for the Long Island Railroad. From 1913 to 1917, LIRR/BRT trains ran from Chambers Street out to the Rockaways, using today’s Jamaica line and a ramp to the LIRR Atlantic and Rockaway Branches; crossbeams under the el on Fulton Street in East New York are all that remains of this service.

Plans to connect the Chambers Street station to el service on the Brooklyn Bridge were on the books before construction of the station started, and the ceiling of the station was built especially high to accommodate such a connection, but it remained unbuilt.

However, the deterioration of the eastern Chambers Street platform had begun long before the 1967 Manhattan Bridge service change. 1931 saw the completion of the so-called Nassau Street Loop, an extension of the line south along Nassau Street and a connection with the BMT Broadway Line’s Montague Street tunnel. This enabled trains to loop both ways through lower Manhattan using the tunnel and the Manhattan Bridge.

After the Nassau Street line was finished in 1931 the eastern platform at Chambers Street was closed, as well as the center platform; a station mezzanine is now in the basement of the Municipal Building, and there are also some closed staircases.

So, for at least seven decades, there has been little or no maintenance on the eastern Chambers street platform, and even in large stretches of the platforms that are still in use.

The Nassau Street-Jamaica line spends little time in Manhattan. It services Williamsburg, Bushwick, East New York, Cypress Hills, Woodhaven and Jamaica, and it is the MTA’s gateway to these neighborhoods, some thriving, some rebuilding and some still stuck in a depressed condition. Can it be that the MTA has deferred maintenance on this line because it doesn’t serve Manhattan primarily?

In 2001, the line performed yeoman duty after the Broadway BMT was shut down after the terrorist attack J trains picked up the slack for the R and N, using the Montague tunnel to travel all the way to Bay Ridge. Briefly, the J was the longest local in the system.

Presently, the MTA is rebuilding the Canal Street station along the line, which is a busy transfer station with the Broadway BMT and Lexington Avenue IRT. The nearby Bowery station has gotten a paint job, which sadly has compromised many of its original station signage. Yet, Chambers Street has remained largely off the MTA’s radar, which is odd, considering that City Hall is close by.

Can it be, despite all the new polish and new toys the MTA has acquired in recent years, that the BMT Chambers Street station shows us the true face of what the subways actually are? It does give us pause to consider what all stations would look like, if careful, regular maintenance is not done.

For a comprehensive look at Chambers Street, including many more photos, see…

nycsubway.org Chambers Street page

Joe Brennan’s Chambers Street page

Harry Beck’s nycrail.com Chambers Street page

Thanks to Forgotten NY webhost Paul Matus for help with this page.

11/2/03