March 21st, 2004: About thirty Forgotten Fans met in (extremely) windy Jamaica, Queens and toured a 4-acre, 350-year old cemetery and an over 250-year old mansion in the geographic center of Queens.

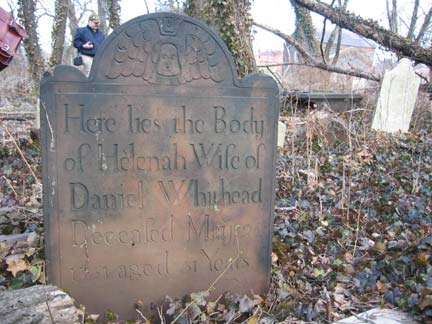

Cate Ludlam, president of the Prospect Cemetery Association, shows off a hand-lettered tombstone from 1728. Cate has been involved with the cemetery, in which is interred several of her ancestors, for about fifteen years.

Weed-strewn Prospect Cemetery dates to the early-to-mid 1600s (some accounts have 1640, others 1668). The Association has to beat back both weeds and vandals in attempting to maintain the Cemetery in presentable condition.

Forgotten Fans tour the front, or “newer” part of the cemetery, facing 159th Street on the York College campus. The older part of the cemetery is the heavier-wooded area, seen in the background at right, in which the oldest stones are to be found. The cemetery was originally arranged along the banks of the now-vanished Beaver Pond, whose name is remembered in the twisting Beaver Road (which once ran along the pond) and Jamaica itself; “Jamaica” is Algonquin Indian for “beaver.”

The Chapel of the Sisters was built in the 1860s and commemorates the builder’s three daughters, who passed away at a young age. The builder’s name was Nicholas Ludlam, an ancestor of Cate’s. While the chapel’s interior is still awaiting enough funds for renovation, its exterior has been stabilized and is in no danger of collapse.

In the 17th and 18th Centuries, prominent citizens were often interred in the very church in which they worshipped. In that era, pews were often sold or rented. Less prominent or poorer people were buried in the churchyard in the 1600s and early 1700s.

The chapel’s interior is dotted with epigrams such as this one, “I will ransom them from the power of the grave.” Note that it’s on both the wood and the marble.

The Long Island Rail Road (Rail Road is two words) runs along the northern edge of Prospect Cemetery. It’s a historic artifact in itself, having incorporated in 1834, though the elevated portion in this area was built in 1930, replacing a surface line.

According to Cate Ludlam, aficionados can tell both the date and, in some cases, the stone carver, by what style ornament was used at the top of the stone. Earlier stones, from the 1600s and very early 1700s, often used a skull-and-crossbones motif, while later graves, from the early to late 1700s, used angel heads with two wings. If the interred was a Mason, Masonic symbols like builder’s tools and hourglasses could be employed. On this one, note the use of the “long s” in “deceased.” This orthography vanished shortly after the revolutionary War.

Cate told us she had been searching for this stone for some time. Elias Baylis, a blind churchman from Jamaica, was imprisoned by the British in a ship (perhaps the infamous HMS Jersey); in 1776 he was released, only to collapse and die in the arms of his daughter while “crossing Brooklyn Ferry.” His story is carved on his stone, which now lies rudely unnoticed.

You’re encouraged to visit the Prospect Cemetery Association’s website (linked above) and do what you can to help the cemetery’s comeback. You can contact Cate at CateL@aol.com.

Forgotten NY’s Prospect Cemetery page

New York Times reporter Robert F. Worth (with pad and pen) was along and wrote a story in the March 22, 2004 edition.

This is actually the original Prospect Cemetery gate on Beaver Road.

Are we really in Jamaica? Yes, we are. The Rufus King Mansion, more properly, King Manor, stands on Jamaica Avenue and 153rd Street. It was originally built in 1730 along the main route to Brooklyn Ferry at the foot of today’s Fulton Street. In 1805, Rufus King, who was born in what is now Maine but was then part of Massachusetts, bought and expanded the property to its present appearance. A bona fide Founding Father, he was a youthful representative at the Continental Congress from 1784-1786, a US Senator from New York in 1789, a Minister (Ambassador) to Great Britain from 1796-1803 (where he impressed the still-hostile Brits after the close of the Revolutionary War), a US Senator again from 1813 to 1825, and ran unsuccessfully for President as a Federalist against James Monroe in 1816.

King, an ardent opponent of slavery, argued: “I have yet to learn that one man can make a slave of another and if one man cannot do so, no number of individuals have any better right to do it.”

The manor’s rooms are painted in rich colors typical of the period when he was in residence. Above is the parlor in which he greeted guests. The pianoforte on the right was King’s own.

All above photos by Mike Epstein, Christina Wilkinson and Harry Cohen.

Forgotten Fans gather at King Mansion.