FIRST of all, we’ll get Houston Street’s derivation, and its unusual pronunciation, out of the way: The street from the Hudson River to Bedford had acquired its name by 1803, when Texas general, senator and governor Sam Houston (1793-1863) was ten years old. Couldn’t be him. Other accounts have the name derived from the Dutch termhuystujn (“garden house”) from the Bleecker family gardens, on which the street was laid out.

Most likely, though, Houston Street is named for a congressman from Georgia, William Houstoun, who married Mary Bayard: her father Nicholas owned the land in Greenwich Village through which he cut the street in the early 1800s, naming it for his son-in-law. Houstoun spelled his name with that extra ‘u’ and likely pronounced his name Howstoon or Howston. Over time the extra letter fell out while the pronunciation remained.

If you’re looking for a Manhattan street named for a Texas general, though, look no further than Worth Street, named for General William Jenkins Worth, a Mexican war hero buried on 5th Avenue and 25th Street; Fort Worth, Texas, also bears his name.

Google Map: Houston Street

(best seen from Firefox)

Houston Street begins at West Street, running along the Hudson River, now part of the redesigned Joe DiMaggio Parkway, though few signs identify the parkway as being named for the Yankee Clipper. Pier 40, its entrance seen here, has become an important recreational facility in park-poor southern Manhattan, with batting cages, driving ranges, kayaking, football, rugby and more.

Houston Street cheats a bit in order to reach West Street: it must pass under a building called the St. John’s Center. It passes a UPS maintenance facility between Washington and Greenwich Streets. Greenwich Street marks the original Hudson Street shoreline, and so it is not perfectly straight: it winds slightly, especially as it reaches western Greenwich Village.

St. John’s Center is actually the southern end of the old West Side Elevated Railroad (aka the High Line) and the name St. John’s Center actually goes back to the 19th Century: it remembers the former St. John’s Chapel of Trinity Church, which stood on nearby Varick Street until it was razed in 1918. The church is also recalled in the suubway station mosaics at the IRT Canal Street station at Varick.

Railroad.net has the whole story on the West Side Improvement. Thanks to the many Forgotten Fans who supplied the link.

375 Hudson Street, home of the Saatchi and Saatchi global ad agency at Hudson and Houston, with its hundreds of windows wrapping around curved edges, echoes the earlier Starrett-Lehigh Building further uptown.

This was also one of the first buildings to employ retro-style sidewalk lampposts when it was built in the late 1980s. The city has sort of appropriated them since then, adding traffic signs.

Between Hudson and Varick Streets, Houston Street shows us the face it once owned all the way to the East River. As we’ll see later, a street widening project turned Houston into a 6-lane behemoth, but it once was a cobbled lane like this for its entire length.

In 2005 Martin’s Bar and Grill certainly had had a presence on Houston just west of Varick for quite a few decades, but by then its “wall dog” ad, vintage 1940s neon sign, and sledgehammer and seashells in the window are all that were left.

[by 2012 the painted ad was still there, but everything else had gone]

Film Forum was founded in 1970 and moved to its present location at 209 West Houston (between Varick and 6th Avenue) in 1989. It’s the kind of theatre you can find only in a major metropolitan area like NYC since it plays American classics, cult films and foreign releases as well. In just the past 2 years your webmaster has caught Sweet Smell of Success; Eyes Without a Face, a French horror film about a mad plastic surgeon; In The Realms of the Unreal, Jessica Yu’s documentary about artist Henry Darger‘s illustrated treatise, which he wrote for 60 years about androgynous children fighting forces of evil; and Donkey Skin, a fractured fairy tale starring Catherine Deneuve.

Gilda Radner (1946-1989) was a charter member in 1975 of the original Not-Ready-For-Prime-Time Players, the first and arguably best comedy team from Saturday Night Live; her characters, still fondly remembered today, included Emily Littella and Roseann Rosannadanna (based on real-life 1970s WABC news anchor Roseanne Scamardella).

Six years after Miss Radner’s death from ovarian cancer, an organization named in her memory, Gilda’s Club, was set up as a support group for those living with cancer and their friends and loved ones. The NYC branch can be found at 195 West Houston Street.

1830s-1840s townhouses on Houston between Varick and Sixth Avenue

At Sixth Avenue Houston Street becomes a six-lane monster, accepting eastbound traffic from Sixth Avenue. Westbound traffic is funneled onto West Houston as well as into the heart of Greenwich Village via Bedford Street. In the 1960s, a third street, to be named Verrazano Street, was due to be cut through to 7th Avenue South, but the plan was defeated. Houston was originally a regular two-lane street but was widened in the 1930s when the IND subway was built beneath it.

Oddly, Houston Street was widened by tearing down houses on its south side between Sixth Avenue and Lafayette Street, but then on its north side between Lafayette Street and Avenue D.

You’re not supposed to call it 6th Avenue, you know.

6th Avenue has a rather involved history. It has been extended both northward (in the mid 1800s, above Central Park) and southward (in 1928, for the IND subway) and has been renamed twice!

In 1945, Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia renamed Sixth Avenue along its entire length south of Central Park “Avenue of the Americas.” Some histories indicate it was done in honor of the new Organization of American States, but the OAS didn’t have a charter until 1948.

When new lampposts were installed along the AOTA in the late 1950s, they came equipped with medallions depicting every country then involved in the Organization, including Cuba, which had not yet succumbed to the Castro revolution.

A street renovation project in the early 1990s removed most of those poles, though two clutches of them, and their rusting medallions, can still be found on the AOTA between Canal and West 4th Streets, and again for a couple of blocks either side of West 57th.

These devices, known as bell bollards, can be found on a couple of cross streets along Houston. They were installed by the NYC Parks Department in 1998 to help keep pedestrians and traffic in their place: if a vehicle comes too close to the median, it will hit the bollard and slide off the bell and back into the street without damaging the vehicle or anyone walking across the median.

In the 1960s an iron fence was installed along the median, but a succession of accidents made quick work of it and most of the fence was gone by the 1990s and all of it by the 2000s.

St. Anthony of Padua Church, 155 Sullivan Street, was dedicated in 1888 and originally couldn’t be seen from Houston Street, until its widening in the 1930s.

Storefont Venus De Milo

Some building fronts the street wideners didn’t get: Sullivan Street, left and Thompson, with distinctive fire escapes, at right.

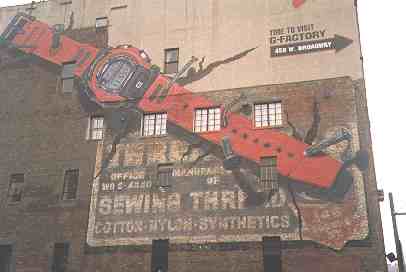

Well, hello there. The south side of Houston from Lafayette Street west has been plastered with gigantic ad billboards; there must have been a technological breakthrough since 2000 or so that has made them affordable to produce. They replace older “wall dog” ads: this one on Thompson had some latterday artwork appended by 1998, when the photo was taken.

Time Landscape, at West Houston and LaGuardia Place, was conceived by artist Alan Sonfist in 1965 and was placed here in 1978. It employs native New York State plants to show NYC as it was before European colonists began arriving in the 1500s.

It’s generally fenced-off to the public, though your camera will fit through the bars or the flowers poke through them.

The hidden Picasso: a reproduction of Pablo Picasso‘s Bust of Sylvette can be found on a demapped portion of Wooster Street just north of Houston on the New York University Silver Towers. Picasso’s original was done in 1934: this is a 1970 enlargement by Norwegian sculptor Carl Nesjär, who was commissioned by architect I. M. Pei.

Christo, who wrapped Central Park in February 2005, wrapped Sylvette in 1972.

This part of Wooster Street, demapped in the late 1960s for the construction of Silver Towers, was given a modern red brick pavement, which hasn’t been replaced for a few years.

The second of Houston Street’s three great independent movie palaces, the Angelika, has been found since 1995 on the ground floor of McKim, Mead and White’s grand Cable Building, which powered Manhattan’s cable cars in the late 1890s and early 1900s. Yes, Manhattan once had an extensive system of cable cars rivalling San Francisco’s. The building housed the enormous machinery that was necessary to run the cars in Manhattan as far north as 36th Street. The cable rails were converted to electricity in the early 1900s, and largely elimiated by buses by the 1940s.

More Cable Building pictures at nyc-architecture.com

The southwest corner of Broadway and West Houston for many years featured an art installation, called “The Wall” consisting of a few dozen aquamarine girders poking out of a blank wall. It was installed in 1972 by artist Forrest Myers. The building owner sued to have it removed in 2003 so he could sell the ad space, but there was nothing there by mid-2005.

All was well by 2011, though.

East Houston’s first building, a new glass-walled incongruity, doesn’t fit in well with the rest of the architecture in the area.

Broadway is the dividing line between East and West streets north to 8th Street, where 5th Avenue assumes those duties.

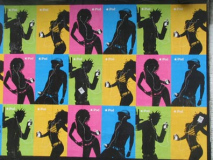

The stretch of East Houston between Broadway and Lafayette Street has always been wide open, with a dearth of tall buildings, which gives advertisers a large canvas to go crazy with ads. This is what NYC advertising looked like in the summer of 2005, when these photos were taken. A word about the iPod, shown lower right: recorded music, and the machines we use to play it, has always been sold as a communal experience: everyone grooved to the same stuff, promoting universal harmony and peace, etc. Top 40 radio could play all genres. No more, though: everyone has their own music and everyone dances alone.

The crown jewel of Houston Street, as far as your webmaster is concerned, is the Puck Building, a Romanesque revival red bricked masterpiece at Lafayette, built from 1884-1892 by architect Albert Wagner. The publishers of the satirical magazine Puck, named for the Shakespearian character from A Midsummer Night’s Dream, had offices here until the 1920s, when the magazine was absorbed by the New York Journal-American. The building was restored from stem to stern in 1995. In the 60s and 70s, this corner was Squeegie Man Central.

Not one but two gilded Pucks can be found here, a smaller one above the Lafayette Street entrance by German sculptor Henry Baerer, and a much larger one at the corner of Mulberry and Houston by Casper Buberl.

A stroll around to the back of the Puck Building on a tiny service alley called Jersey Street reveals old-fashioned shutters of various shapes on all the windows. Not much sun gets through here to make the shutters practical, but apparently the building once had much more exposure.

We now arrive at the Bowery, an ancient road that is desperately trying to upgrade, with luxury condos rapidly replacing the flophouses. At the southeast corner of Houston we have one of the Bowery’s then-longstanding businesses, Adams Restaurant Supplies. As shown on my Bowery page, the ancient throughfare assumes many guises in its march from Chinatown north to Cooper Square, from jewelry to lighting to kitchen supplies. It will always be remembered as a bastion of flophouses and dead-end dives that grew out of a much earlier incarnation as a street full of bars and theatres, but the Bowery’s days as boulevard of despair are receding quickly now.

I encountered McGurk’s Suicide Hall in its funeral shroud in June 2005. The former dive, home to a prostitute’s suicide craze in the 1890s giving the building its sobriquet, was razed the next month. This may be the last picture taken of the old place. A new complex called the Avalon now occupies the site.

The Liz Christy Community Garden was planted in an empty lot at the northwest corner of Bowery and Houston by Christy and her organization, the Green Guerillas, in 1973. It currently is behind a locked gate, though the GGs hope to get it open again sometime in 2005. (It reopened in 2007.)

Looks like somebody remembers theMC5. The politically-themed Detroit 60s group has re-formed around guitarist Wayne Kramer (singer Rob Tyner passed away in 1991 and lead guitar player Fred Smith in 1994) and has been playing some shows in Brooklyn.

East of the Bowery Houston Street serves as the boundary line between the Lower East Side and the East Village, and informally, the boundary between the “named” streets and the “numbered” streets; 1st and 2nd Avenues begin their uninterrupted journey north to the Harlem River here. Above: the beginning of 2nd Avenue at the former Church of All Nations and Cuando Community Center.

[this building, along with the rest of the block, was razed in 2011]

Irreplaceable Artifacts has been forced to vacate its long-time perch at 2nd Avenue and Houston, leaving behind a scene reminiscent of the last days of Pompeii. See that “WB” ironwork? It’s originally from the Williamsburg Bridge, removed during its recent renovations; someone should really take care of that object. Accounts say the MTA has acquired the property to build an entrance for the Second Avenue Subway, which has been in planning for about eighty years.

MTA Touts Second Avenue Subway … in 1972

At the 1st Avenue end of the 2nd Avenue IND station you’ll meet Allen Houston, the oft-injured Knicks guard.

OK, I know he spells his name Allan Houston. And, he pronounces it like the general.

The Yonah Shimmel Knish Bakery is a longtime Houston Street tenant between Forsyth and Eldridge, emblematic of the old Jewish dominace of the Lower East Side, but development here is now rampant: for how much longer will it be here?

A few doors down is Sunshine Cinemas, the third and newest of Houston Street’s three great independent movie palaces. It opened as a vaudeville house in the 1890s and as Sunshine Cinemas in 2001.

Mural by Chico at Eldridge and Houston, since covered.

I’m not sure if this Chico from further east on Houston has survived.

Beaux-Arts front east of Eldridge.

Joel Russ opened a pickled herring shop on Orchard Street in 1914. According to Historic Restaurants and Shops of New York, Russ had an irascible, argumentative personality, not an asset in the retail biz, so he put his three personable daughters to work behind the counter. The business evolved into a gourmet seafood deliacies emporium, still with a vintage 1940s neon sign. One of the daughters’ sons, Mark Federman, runs the shop now.

Katz’s Deli at Ludlow and Houston has been sending salamis to boys in the Army since 1888. It features another classic neon sign in front as well as decades old painted signs on the side. The deli was founded by the Iceland family; the Katz brothers bought into it in the early 1900s. All the food is prepared on premises, but actually getting to it is a bit confounding; confusion reigns on the food line, where you pick up a ticket first. The shop has served four Presidents, who presumably didn’t have to bother with the tickets, as well as Billy Crystal and Meg Ryan; Meg pretended to be engaged in a pleasurable activity during a movie scene filmed here.

But what is a “Wurst Fabric” sign doing here? It is an American transliteration for a Yiddish term for homemade sausage.

The nearby Knitting Factory (formerly on Houston) was once a knitting factory, Arlene’s Grocery was once a grocery owned by an Arlene, and the Mercury Lounge, on 217 Houston between Ludlow and Essex was once a servant’s residence to the nearby Astor Mansion, Garfein’s Restuaurant, and later a tombstone retailer; the interior of the rock club has preserved mementoes of that incarnation, as well as the storefront sign, redolent of stone carving.

It’s not just another block of luxury apartments:Michael Rosen’s 13-story “Red Square” at East Houston and Avenue A has been open since 1989 and features a statue of Vladimir Lenin, defiant in the post-Soviet age, and a misnumbered “Askew” clock.

KISS, largely a NYC band, was lauded at Nice Guy Eddie’s on Avenue A and Houston. Eddie’s closed in early 2012.

Former Provident Loan Society of New York, southeast corner Houston and Essex

The Manhattan Bridge is framed amid Suffolk Street as seen from Houston.

The artist may have been to Co-op City, since that’s the only place you can get a NYC green-and-white street sign with Albert Einstein‘s name on it (Einstein Loop)

A pair of venerable buildings, at Clinton Street (above) and Avenue C (Loisaida Avenue) . Does the Angelica Deli know about Angelika Film Center several blocks to the west? …

Gustave Hartman Square, Avenue D and Houston, is named for a 1930s Municipal Court Justice and philanthropist, according to Sanna Feirstein’sNaming New York.

Ignacio’s serves Latin-American delicacies noted on its sign, some of which are displayed in its window.

We note PS 188, on the north side of East Houston between Avenue D and the FDR Drive, since it preserves tiny, one-block Manhattan Street as a service alley. Manhattan Street has been demapped, and a much-longer Manhattan Street in uptown Manhattanville has since been renamed West 125th Street and then Martin Luther King Boulevard. Fear not, there’s still a Manhattan Avenue (on the Upper West Side) and in Brooklyn, in Williamsburg and Greenpoint. Could you picture Manhattan with a Brooklyn, Bronx, Queens or Staten Island Avenues?

East Houston ends with a traffic circle and simple ramps to the East River (FDR) Drive that look much the same as they did when first constructed, with the Williamsburg Bridge forming a backdrop on the south

In the end, there’s always baseball.

Photographed: June 16, 2005; written, July 10-11, 2005. Thanks to William Hohauser for additional information.

15 comments

Your comment on the photo of the de-mapped piece of Wooster St. says that it got a red-brick pavement, but that’s not correct. It’s all Belgian block.

My Dad owned Garfein’s Restaurant where the Mercury Lounge is now….

I have pictures of the exterior and interior and an ad from the Jewish newspaper, the Forwards, announcing its opening in June1925.

It was a dairy restaurant and very busy with local customers!

I have a wedding photo of my grandparents along with their invitation–they were married at Garfein’s in 1926. I’d love to see whatever photos you have… 🙂

Hi, I’m doing a project on forgotten New York places and what’s become of them and I would love to include your father’s restaurant. Would you be willing to share those photos with me?

I’d love to see the pictures of Garfein’s. I just found my parents’ wedding certificate. They were married there in 1938. Is this online?

My parents’ wedding celebration was at Garfein’s in November 1942. I found receipts and a menu for the event that my mother had saved. Dinner for 14 couples was $59.50. However the banquet facility was at 10-12 Avenue A, where Union Market is now.

That’s the address on my grandparents’ wedding invitation. They were married there in 1926!

RIP Billy’s Antiques & Props and Billy’s neighbor the giant mural. We have patronized and enjoyed these two NYC originals for many decades; Houston Street from Bowery to Elizabeth will never be the same. I have dozens of photos (on Poloroid, 35mm slide, film and digital) of the great mural (there is an ominous scaffold in front of it at the moment) and wonder if anyone or any place has a comprehensive library of the murals?

Nonetheless Houston is still one of the greatest streets.

Many thanks for the great short article, I was looking for specifics such as this, going to have a look at the other posts.

The wrought iron shutters on the Puck Building (and other neighborhood former factories) were not to keep out the sun, as you suggest.

Rather, it was to prevent glass from shattering during loft fires and injuring people. It seems a bit overkill. I was told that the shutter-requirement was made law in the early decade of the 20th century by an alderman, who later went to prison for corruption. Could this code requirement be one reason?

But the code requirement still persists. When I added a bedroom on my roof in SoHo recently, still zoned for manufacturing, I had to install wire-mesh windows. The architect said it was to prevent the glass from shattering and exploding outward.

The shutters on the Puck Building (and other former SoHo manufacturing buildings) were not to keep out light, but was to prevent the glass from shattering and exploding outwards, injuring people, during loft fires.

“Wurst Fabric” is a misspelling of “Wurstfabrik”, German for “sausage factory”. Not quite so charming in English.

Many years ago, when they were building University Village, I worked for my father , who had a manufacturing plant on Prince St., across from the post office at the Corner of Greene St. Many times i worked at night and very large rats would scamper around the loft. Exterminators were constantly there leaving poisons of some sort. Frequently when these rats died, the order lingered for weeks. I don’t know how

the daytime employees could stand the smell.

What will become of the rat infestations after the current Covid 19 ends.

Any information on the Kiwi Bar on East Houston, 1960’s. It catered to merchant marines when their ship was in port. Fun dive, good hamburgers, lively dark bar a few steps down from

the street.

I worked in Yonah Schimmel’s on Houston occasionally during the mid to late 80’s – that neighborhood was crazy 24/7 back then! The place was always full of “interesting characters” during those days – back when Sasha (Alex) was the cook, and “Shelly Keitz” the owner. They also had another shop on the upper east side back then – catacorner to Gimbels on Lex.

I had my daughter stop by there recently, and sadly, some of my favorites are no longer made there.