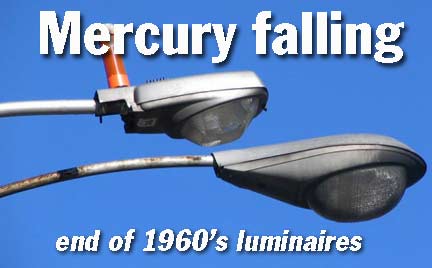

In 1963, the life of a 6-year-old lamppost enthusiast changed irrevocably: the cast iron Type 24M “Corvington” poles that had dominated the streets of Bay Ridge disappeared seemingly overnight, with mostly all of them replaced by streamlined aluminum poles with octagonal shafts. Most of the shafts were topped by straightarm masts, some by cobra-necked ones, and the masts were nearly almost always completed by one of two luminaires that gave off a strange, otherworldly (to my 5-year old eyes that were used to the soft white incandescent glow) whitish-green glow produced by mercury vapor.

The new era had begun.

The stage was set for the great Luminaire Rivalry of the 1960s.

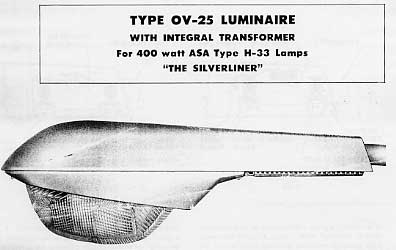

LEFT: General Electric M 400 –“I’m here to light the streets”. RIGHT: Westinghouse Silverliner OV-25 —

“Howdy folks!”

(Thanks to Rick Duskiewicz for providing clean GE and Westinghouse logos.)

By the thousands they came, beginning in 1960 and spreading out over New York City’s over-9000 streets. The new “cobrahead” luminaires, so-called because, viewed from underneath, they resembled a cobra’s flared cowl, were a novel replacement for 1920s-1950s schemes that mostly featured “teardrop,” “gumball” or cuplight” lumes that pointed directly down at the street they were illuminating. These new models featured new wiring that connected them horizontally to their masts, making for a new, streamlined profile. They couldn’t be easily atached to the old castiron posts, hastening their temporary demise. (New ornate iron posts with teardrop lumes featuring modern ultra-bright sodium started appearing around 1980.)

I noted with interest in 1963 as the GE M400s spread up Bay Ridge’s Sixth Avenue, Fort Hamilton Parkway and most side streets, while Fourth and Fifth Avenues received Westy Silverliners. (Of course it wasn’t till many years later until I knew what companies produced them, and my 5-year-old head didn’t assign them names.) I did, however, notice a distinct difference in mien and attitude between the two competing models. And I had a favorite.

The General Electric M400, it seemed, was the more dour of the two, had more of a businesslike air, yet was rather more sincere than its less serious counterpart. Meanwhile, the Westy Silverliner was more raffish, more jaunty, and even bore something of a resemblance, at least in attitude, to a favored cartoon character of mine, Bugs Bunny. The feeling was rather more frivolous and fun-loving. Yet, you didn’t quite trust it to keep the streets lit as its rival, the GE M400, would.

Was my anthropomorphization of these two streetlight luminaires all that unusual? As a kid, I made out all letters of thealphabet to be male, except for “F”, “P”, “S” and “Y,” and all numerical digits to be male, except “2” and “4.” Before we get too much further into Oliver Sacks territory, I’d like to mention that there seemed, at this time in American manufacturing, an inclination to give many inanimate objects a human-looking “face”; just look at automobile models of the 1950s, or these General Motors “fishbowl” buses that first saw service in NYC in 1960, about the same time our luminaires first showed up.

Was my anthropomorphization of these two streetlight luminaires all that unusual? As a kid, I made out all letters of thealphabet to be male, except for “F”, “P”, “S” and “Y,” and all numerical digits to be male, except “2” and “4.” Before we get too much further into Oliver Sacks territory, I’d like to mention that there seemed, at this time in American manufacturing, an inclination to give many inanimate objects a human-looking “face”; just look at automobile models of the 1950s, or these General Motors “fishbowl” buses that first saw service in NYC in 1960, about the same time our luminaires first showed up.

And I wasn’t alone. Lamppost king Jeff Saltzman dubbed the GE M400 the “Disgusted” (and its later incarnation, the M400A2, the “Doubtful“) and the Westy OV-25 the “Cheerful” and he came to these charactrizations quite independently from me.

(Jeff and his new family have decamped to North Carolina, leaving me to be the king of NYC streetlight webmasters.)

My preference was always for the Westy OV-25. It seemed more welcoming, and yes, more cheerful. And, it seemed to be the underdog. There was no way to do a count but it seemed that the Department of Transportation simply used more GE M400s. (Perhaps they picked up on its subtle “old reliable” characterization.) And, the Westy seemed to hang out in my favorite parts of town, like Coney Island.

General Electric M400

General Electric has been a player in the consumer electrics business since 1890 when the firm was formed by Thomas Edison as an amalgamation of his various companies. GE was selling electric fans by the mid 1890s and developed street lighting shortly thereafter. In the first few decades all of its street lighting models were teardrop incandescents, but at the dawn of the Fab Fifties came a major development…

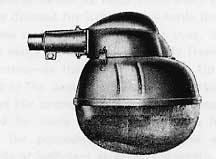

LEFT: The first of the major mercury lamps, the GE 109 arrived in 1948, and reflected the USA’s ongoing move to automobile traffic and away from the railroad, even though the USA’s interstate expressway system was just then getting underway. Promotional materials describe it as suitable for “a) high-speed expressways; b) interurban freeways, heavy traffic; c) main urban traffic arteries; d) business streets with 2-3 story buildings; e) complex interchange areas; f) bridges and viaducts.” Much was made of its “distinct modern appearance: in an age when most city streets still had their ornate cast iron posts from decades before.

A major player in many big cities (they could still be seen on Beacon Street in Boston well into the 1980s), the GE 109 really didn’t become a major element in NYC with the exception of one street: the Avenue of the Americas, where they teamed up with then-new octagonal shafts and distinctive medallions containing every flag of the Americas. The GE109s only lasted on 6th Avenue for the better part of a decade, however, and were replaced in the early 1960s with a mishmosh of GE M400s and Westy OV-25s, until 1968 when the avenue got the first of the new GE M400A2’s, ushering in the era of the bright, intense sodium lamps, which dominate today. (image from 1951 GE catalog)

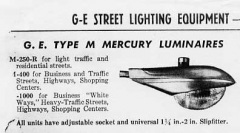

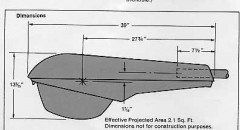

RIGHT: 1959 was the year that the GE M400 arrived. It was accompanied by a “condensed” version, the GE M250R, which never masde its way to NYC streets (though I recall heavy use in the New York capital district area). The M250’supdated successor, which quite resembled it though with a sodium light, was produced from 1970 to 1985 and remains NYC’s title-holder for most frequent luminaire at the present.

For “personality” however, these new GE lumes just can’t compete with the GE M400, the Droopy of the streetlighting world.

(image from 1961 GE catalog)

Also noted in the catalog was the massive GE M1000, which resembled the M400’s older brother you wouldn’t want to mess with. The M400s cost a cheap $189 for a 120/240 volt model and $171 for just 240 volts, and of course, all were 400 watts: the M number referred to voltage in the GE series.

While GE M400s are increasingly rare in NYC these days, they pop up now and then and do have a stronghold or two…

I had to shoot straight into a strong June sun to snag this GE at 110th Street and 69th Avenue in Forest Hills.

LEFT: Storms gather over a GM400 citadel, Brookville Boulevard, in Rosedale, Queens. These GEs were replaced in 2010 by the new 2009 version of the GE M400.

RIGHT: A lone GE at Fort Schuyler, Bronx.

It’s a lamppost maven’s axiom that styles long outmoded can sometimes be found underneath overpasses and elevated trains. A GE M400 lurks on McDonald Avenue north of Avenue X.

As multimillion-dollar condos rise near Greenpoint, Brooklyn’s McCarren Park, the nouveau urban hotspot (where your webmaster had an apartment with one electric outlet and a bathtub in the kitchen in 1982) a lone GE M400 overlooks the changing scene, and remembers the scuzz of the past.

In busy Chelsea, you’ll find a pair of GE M400’s the Department of Transportation forgot to remove many years ago when this stretch of 9th Avenue received a set of M2 guy-wired stoplight/cobra neck combos.

Alongside, we see its replacement…the newest incarnation of the Westy OV-25 (from 1979)! Oh, the ignominy! At right (22nd) the GE is worse for wear and has lost its glass reflector disk and most of its inner wiring. Its replacement in this case is American Electric’s 115 model.

Westinghouse OV-25

It’s fitting that GE’s chief rival in illuminating NYC streets should come from the firm originated by George Westinghouse (1846-1914) –Thomas Edison’s first great rival. George Westinghouse’s career in invention began in 1881 when he perfected an automatic electric block signal designed to slow down and stop trains using compressed air. Purchasing patent rights from Nikola Tesla he championed alternating electric current, in opposition to Edison’s direct current, and went on to develop a practical means of transmitting natural gas to heat homes and businesses.

In the 1940s Westinghouse, the company, developed the AK-10 luminaire, commonly referred to as the “cuplight.” The model swiftly began to dominate NYC streets as it took over cast-iron and octagonal poles alike from previous bell and gumball lumes: it was wildly adaptable and could hold both incandescent bulbs and mercury lights. It still has pockets of strength in Nassau County: q.v. photo left, a parking lot in Westbury.

It was molded to present an optimistic, sunny appearance, much like its “mercurial” successors would.

(photo: Jeff Saltzman)

The Westy OV-25 was introduced in 1957 (the year your webmaster was introduced), which means it might well have been the very first “cobrahead” luminaire; in any case it was the first in common use. It didn’t get its coming-out party in NYC, however, until about 1960 (I wish I could pinpoint when excatly the M400s and OV25s first appeared in NYC, but the person in the DOT who can answer that question is either retired or gone by now.)

The Westy OV-25 was introduced in 1957 (the year your webmaster was introduced), which means it might well have been the very first “cobrahead” luminaire; in any case it was the first in common use. It didn’t get its coming-out party in NYC, however, until about 1960 (I wish I could pinpoint when excatly the M400s and OV25s first appeared in NYC, but the person in the DOT who can answer that question is either retired or gone by now.)

1961 Westinghouse brochure

The OV-25 has gone through two distinct incarnations….

The first OV25 was produced between 1957 and 1963 and featured two doors (the openings repairmen used to reach the wiring) as well as the photocontrol (the regulator that turned on the lamp at dusk) set forward on the chassis. These are now quite rare at least within the five boroughs, which is why I am using photo left, shot in California by Silverliner Guy, who agrees with me that these are the coolest lamppost luminaires of all time.

CENTER: on a Throgs Neck Expressway (Bronx) service road by Jeff Saltzman.

The OV25s were accompanied by lumes of lower wattage, the OV 12 and OV 15. With the exception of a couple streets in Glen Oaks, Queens, which have OV15s, they never caught on in NYC like their bigger cousin.

RIGHT: Stillwell Avenue and Avenue T, Brooklyn

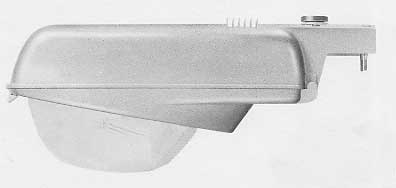

In 1965 came the Great Photocontrol Shift, as the new OV25s moved it toward the back of the chassis, rounded the lines and, if anything, made a great original design even better. There was also one, not two, openings to the inside wiring. These lumes were produced by Westinghouse until 1982 when the line was sold to Cooper Lighting, which [apparently] still produces them in Canada. Oddly, these new OV25s could be outfited with sodium bulbs, and a few did pop up here and there, but he practice never caught on, and newer models from GE, Westy, Thomas & Betts/American Electric and many other manufacturers would make the high-intensity sodium lamps that began to light NYC on a wide scale beginning in 1972.

Parks are often a prime venue to find outmoded lumes as a walk around Madison Square proves. Two Westy OV25s, second edition, survive here.

Westy Silverliners in Jackson Heights, Queens, and Yonkers, NY

Today the Silverliners are quite scarce indeed in New York, but just cross the northern border to Yonkers, and you’re in OV25 heaven: they swarm there! As a rule in the 5 boroughs, though, they are there because the DOT has not gotten around to removing them.

In 1979 yet another OV25 incarnation arrived from Westinghouse, this one completely sodium-friendly. This one can be seen on hundreds if not thousands of NYC lampposts today, inclusing one on 9th Avenue pictured above.

In 1979 yet another OV25 incarnation arrived from Westinghouse, this one completely sodium-friendly. This one can be seen on hundreds if not thousands of NYC lampposts today, inclusing one on 9th Avenue pictured above.

1979 Westinghouse brochure

Hoboken, NJ remains a stronghold of mercury lumes, with a Westy OV-15 and GE M400, illustrating its greenish-white light.

And One More

At the dawn of the mercury era in the Swingin’ 60s, a third luminaire appeared in very select situations: parks, expressways, service roads. It never caught on (I’ve never discovered the manufacturer) and one lone specimen remains, off Jewel Avenue at the southern end of Flushing Meadows-Corona Park. (Its partner is a de-glassed OV25.)

2/19/06