My first memories of Williamsburg came during ages 14-17, when our high school bowling team (on our way to getting whomped by St. Francis Prep and Xaverian) would pile into a Dodge van and trundle up Kent Avenue on our way to the lanes (in a deserted section of Greenpoint at Humboldt and Moultrie Streets). In those days, Kent was rather more bustling than it is now; it still had railyards, and the Domino sugar factory and Schaefer brewery were still quite active (Schaefer would close for good in 1976, when I was 19). It is now the site of a real estate development with water views.

In subsequent years I would bike up Kent or Bedford, marveling at the demarcation line along aptly-named Division Avenue between Hasidic and Hispanic. Williamsburg is large as Brooklyn neighborhoods go, stretching all the way from Flushing Avenue north to McCarren Park north and south, and from the East River/Wallabout Channel east to Union Avenue, where East Williamsburg begins. In those years, the 1970s, Williamsburg was bleak indeed but through all of that had a busy Polish enclave centered on Bedford Avenue in the “North” streets, Hispanic in the “South” streets and Hasidic between Flushing and Division Avenues.

These sunbleached “Northside” signs preceded Williamsburg’s ‘makeover’ in the mid-1990s.

These sunbleached “Northside” signs preceded Williamsburg’s ‘makeover’ in the mid-1990s.

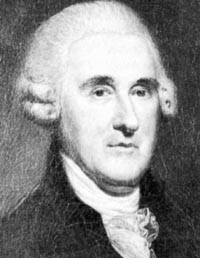

Williamsburg was first settled by Europeans in 1638 when the Dutch West India Company purchased the region from the Canarsee Indians. As Dutch farms faded away or coalesced into small hamlets or villages throughout the 18th century, a community finally emerged and in 1792, wealthy Manhattanite Richard Woodhull purchased property, later hring Colonel Jonathan Williams to construct as street grid and subdivide properties; Woodhull named the community for the colonel. Urbanization, though, wouldn’t follow until the late 1820s, as by then ferries brought in settlers from Manhattan and the new Brooklyn and Newtown Plank Road (today’s Flushing Avenue) and the Williamsburgh and Jamaica Turnpike (Metropolitan Avenue) were built in the first few years of the 1800s. The opening of the Erie Canal in 1825 helped to greatly increase area commerce; by about 1850 it was a city of about 35,000, and in 1855 it was annexed by the City of Brooklyn. A full concise Williamsburg history can be found in Brian Merlis’ Brooklyn’s Williamsburg(h).

The Lost Signers of the Declaration of Independence

Throughout New York City, entire neighborhoods have streets named from one theme. In Baychester in the Bronx, all the streets are named for former NYC mayors. Rosebank, Staten Island, has a small posse of streets named for classical composers. A relatively new neighborhood in Staten Island developed in the 1970s features 1960s astronauts’ names, with lanes named for Gus Grissom, Deke Slayton, Alan Shepard, Wally Schirra and others; strangely enough there’s no Glenn, but a Glen Road.

Williamsburg’s in the club as well: most of the streets are named for signers of the Declaration of Independence. Not every signer is represented, but most are. Ben Franklin, George Clymer, George Taylor, James Wilson, John Morton, and George Ross of Pennsylvania; Caesar Rodney of Delaware; William Hooper, George Hewes and John Penn of North Carolina; Edward Rutledge, Thomas Heyward Jr., Thomas Lynch Jr., and Arthur Middleton of South Carolina; George Walton of Georgia; Elbridge Gerry of Massachusetts; Josiah Bartlett, Matthew Thornton and William Whipple of New Hampshire; Stephen Hopkins and William Ellery of Rhode Island; Richard Stockton and John Hart of New Jersey; George Wythe, Richard Henry Lee (or Francis Lightfoot Lee), and Benjamin Harrison of Virginia… all have named streets in Williamsburg or Bedford-Stuyvesant named for them. John Adams, John Hancock, Francis Lewis, Thomas Jefferson, and Charles Carroll have named streets in other Brooklyn neighborhoods.

Some are missing: Rush Street (Benjamin Rush of Pennsylvania) was lost to urban renewal in the 1970s…Gwinnett Street (Button Gwinnett of Georgia) was absorbed by Lorimer Street in the 1800s; and then there’s McKean Street, named for Thomas McKean of Pennsylvania…

Of course, there never was a McKean Street. The street is actually named Keap Street; a long-ago administrator or mapmaker mistook a handwritten transcription as being “Thomas M. Keap”, and not being a student of history (to be fair, can you name more than five signers of the Declaration?) misnamed the street, which has never been renamed.

Kent Avenue

Kent is one of Brooklyn’s oddly-shaped avenues. It begins without fanfare on DeKalb Avenue just a couple blocks east of Pratt Institute and is just another side street on the border of Clinton Hill and Bedford-Stuyvesant, until it reaches the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway at about Penn Street. It skirts the eastern end of the Brooklyn Navy Yard, offering tantalizing glimpses of the busy industry and former shipbuilding activity inside, and then curves along the shoreline of the East River (as do the other major avenues of Williamsburg’s street grid) before changing its name to Franklin Street without fanfare in Greenpoint (Franklin was built as a turnpike to Queens by Brooklyn and Queens developer Neziah Bliss).

The King of All Buildings seems to loom more precipitously along battered Kent Avenue than in any other “outer-borough” locale. Only in Laurel Hill-West Maspeth, where it looms above cemeteries, or perhaps the New Jersey Meadowlands, where it rises above the horizon abruptly, does the Empire State Building clearly display its size better than here, though it can be glimpsed from any NYC neighborhood (only a better telephoto lens prevents me from demonstrating that). However, Kent Avenue’s view of the 1931 masterpiece, seen here from an auto pound, will likely be severely compromised.

The King of All Buildings seems to loom more precipitously along battered Kent Avenue than in any other “outer-borough” locale. Only in Laurel Hill-West Maspeth, where it looms above cemeteries, or perhaps the New Jersey Meadowlands, where it rises above the horizon abruptly, does the Empire State Building clearly display its size better than here, though it can be glimpsed from any NYC neighborhood (only a better telephoto lens prevents me from demonstrating that). However, Kent Avenue’s view of the 1931 masterpiece, seen here from an auto pound, will likely be severely compromised.

New York’s waterfront history shows that it has mostly been closed to the public throughout the centuries. New York was once a great port city and the maritime trades as well as heavy industry have always dominated NYC’s waterside areas, with the notable exceptions along Brooklyn and Queens’ south shores. In the 1880s, developers such as the Long Island’s Rail Road magnate Austin Corbin and others built grand exclusive hotels in the Coney Island and Manhattan Beach areas to take advantage of the waterside breezes. In the early 2000s, a parallel situation is arising as developers have grand plans for Williamsburg’s waterfront.

Dozens of blocks along Kent Avenue have been recently rezoned for residential development. A massive residential development, “The Edge” will soon be built where these empty lots are (seen here in early 2005) featuring 1000 units and parking for 1000 cars. The developers also promise a waterfront esplanade with a recreational and “water taxi” pier.

Whatever happens, these views of Manhattan from Kent Avenue will soon be rendered utterly changed.

There has been a great dealof water taxi discussion over the past decade, quite naturally in this city surrounded by water. But the concept, except for the Staten Island Ferry, has never really taken off.

Strictly speaking “The Edge” will be built from North 5 to North 7 Streets, on top of the Cross Harbor Railroad, whose tracks, engines and boxcars had been in evidence here as recently as the early 1990s. Very little of Williamsburgh’s railroad history remains: passenger service once ran from the East River and connected with what became the Long Island Rail Road in Queens. Service ended between Williamsburg and Bushwick by the 1880s, but even now, the Bushwick LIRR branch is open for freight, and freight service persisted on the Evergreen Branch until the mid-20th Century. But evidence of rail can be seen only in these tracks crossing Kent Avenue at about North 5th.

When “The Edge” gets built. Kent Avenue, mostly silent for many years, will be bustling again. The Domino Sugar plant, seen in shadow at right, is also ripe for condo-ization after closing in 2005.

These area residents’ pleas for the area zoning to remain unchanged were unheeded. As early as 1998,Williamsburg residents feared that the area would change.

The jury’s out on The Edge. When it’s built will all Williamsburgers get to experience the shoreline, or just the well-heeled residents? That’s a question they’re asking on Furman Street, too, as they get ready to build a park from Atlantic Avenue all the way to Empire-Fulton Ferry State Park, with the price tag being the inclusion of, you got it, high rise waterside buildings. Clearly development is called for on Kent Avenue as well as Atlantic Terminal (which has been in development one way or another since 1986!)…but the scale is all wrong. Developers stopped building for the middle class long ago; these days it’s a throw-in in larger luxury developments. Your webmaster and those in his wage bracket get the crumbs from the table.

Grand Street

Grand Street/Grand Avenue stretches through Williamsburg, East Williamsburg, Maspeth, and Elmhurst from the East River to Queens Boulevard’s junction with Broadway (Broadway of Queens, that is). Many of Brooklyn, or Brooklyn and Queens’ longest streets begin in Williamsburg, such as Grand, Metropolitan Avenue and (Brooklyn’s) Broadway.

Grand Street from Kent Avenue, 1995.

Unusual building, Grand Street east of Kent Avenue, former North Side bank, then Manufacturer’s Hanover (or Handover, as Ralph Kiner would say). Name that truck!

Grand Street was opened in 1812 by Williamsburg landowners James Hazard and partner Thomas Morrell from the East River to about the present location of Roebling Street. It was most likely named for Manhattan’s Grand Street, since the partners opened a ferry service between the two Grand Streets. (A ferry also operated between Manhattan and Brooklyn’s two Fulton Streets for the better part of two hundred years, ending in 1924.)

Rough and ready Grand Ferry Park, at Grand Street and the East River, marks the site of Morrell’s Landing, where the ferry arrived from Manhattan. (Richard Woodhull and David Dunham also ran ferry service to Manhattan from Williamsburg in the early 19th Century.) This ferry remained in operation until 1918; with the Williamsburg Bridge opening in 1903, ferry customers dwindled in number. New developments along the water edge in the early 2000s herald a new ferry era, but will it catch on?

Driggs Avenue

Like Kent Avenue, Driggs Avenue follows a convoluted route. It begins at Meeker and Morgan Avenues west and southwest in East Williamsburg, through Greenpoint, cuts through McCarren Park then through Williamsburgh’s heart to Division Avenue. The southbound B61 bus, which runs from Long Island City through Greenpoint, Williamsburg, Fort Greene, downtown, Cobble Hill and Red Hook, runs along Driggs. The street was named for Edmund Driggs, the last Williamsburg village president before its incorporation as a city.

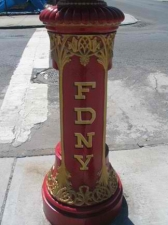

On Driggs Avenue you’ll find the city’s handsomest nonfunctional fire alarm box (many were turned off and disconnected during the Giuliani administration. I detect the handiwork of aspiring firefighter Dave Herman here, whose City Reliquary, a must-see Williamsburg attraction, just keeps on growing, just having acquired new quarters at 370 Metropolitan Avenue. It seems fitting that there’s a decorated firebox here, since Driggs, among other things, was the Williamsburg City Fire Insurance Company president.

Louis Jacobs and Son, on Driggs across the street from the Reliquary fire alarm, has been acquired by Queen City Paper of Erlanger, Kentucky, which, it would seem, is near Cincinnati. Not sure if Jacobs and its old signs will continue operations from here.

This ‘storefront’ on Driggs near North 7th is just a block away from Williamsburg’s heart, at the BMT L line station at Bedford Avenue, yet it is far, far away from Williamsburg’s present scene that migrated from the Lower East Side in the mid-1990s, as clubs, restaurants and boutiques took root, and young professionals followed. It seems like a ghost. Was it a bar or social club? The object on the right, which once held a red, white and blue barber pole sign, is the clue that at one time, it was a barber shop. It’s fuzzy on this photo, but the door is numbered 338 – Driggs Avenue’s old numbering system. The numbers on this block are otherwise in the 500s.

North

Time was, most of Williamsburg’s streets were numbered. North and South streets, which run roughly east to west, use Grand Street as the meridian, with North 1st to 15th north of Grand, and South 1st to South 11th Streets south of Grand. However, Williamsburg’s main routes, Kent Avenue, Wythe Avenue, Berry Street, Bedford Avenue, Driggs Avenue, Roebling Street, Havemeyer Street, Marcy Avenue, and Rodney, Keap, Hooper and Hewes Streets, were also numbered from 1st to 12th Streets. Formerly Williamsburg had intersections like 4th and North 4th Street (a chiseled sign on Bedford and North 4th, above the former Clovis Press, earlier the former Downer’s Pharmacy, will attest) and so on. The streets were given names after Williamsburg was annexed to Brooklyn in 1855 to avoid duplicating older numbered streets.

Though Queens is often accused of having a confusing numbered street system, consider Brooklyn’s: its oldest group of numbered streets, which originated in the City of Brooklyn before it was consolidated with NYC in 1898, begins with 1st Street in Park Slope and ends in 101st Street in Bay Ridge; an intersecting numbered avenue system begins with 1st Avenue in Sunset Park and ends with 28th Avenue in Bath Beach. But it doesn’t end there. After other towns in Kings County such as New Utrecht, Gravesend, Flatbush and Flatlands were annexed to Brooklyn in the late 1800s, it was considered more expedient to give any new streets that were built there either letters or numbers; hence we have East 1st to East 108th east of McDonald (formerly Gravesend) Avenue, and West 1st to West 37th Streets west of McDonald.

But it doesn’t end there either. When Sea Gate, a private development, was built at the western end of Coney Island at Norton’s Point in the early 20th Century, it was decided to continue the “West” numbering system, beginning at 37th and extending to 51st. They’re not called “West” streets, however; instead, they’re “Beach” 37th to 51st.

There’s a set of “Bay” streets in Bath Beach southwest of 86th Street that begin with Bay 7th and end with Bay 54th. Why begin with Bay 7th? They formerly began with Bay 1st, but Bay 1st through Bay 5th (which were likely on drawing boards but never constructed) were eliminated by the construction of the Dyker Beach Golf Course in the early 20th Century. Why not just begin with Bay 1st, anyway? Too easy! By the way, there is no Bay 9th, 12th, 15th, 18th, 21st, 24th, 27th, 30th, 33rd, 36th, 39th, 42nd, or 45th streets, either; they are replaced by 15th through 27th Avenues.

That’s not all. Brighton Beach has an incredibly complicated maze of alleys, walkways and paths, all of which used to bear names, but each is now called “Brighton” something-or-other, with Brighton 1st Lane, Path, Place, Road, Street, Terrace, and Walk, and so on, up to Brighton 15th whatever.

We’re just getting started. Canarsie has a set of “Flatlands” 1st to 10th Streets between East 105th and 108th Streets on its eastern end, and “Paerdegat” 1st to 15th Streets between Paerdegat Avenue North and East 80th on the western end.

That’s not all, either. Cobble Hill has 1st through 4th Places between Smith and Henry Streets. And, there’s a West 9th Street that runs from Smith to Columbia that is, well west of 9th Street proper.

I digress.

St. Francis Prep, now a neighbor of your webmaster in fab Flushing, occupied the building on the right, now Boricua College, on 186 North 6th between 1952 and 1974.

Mid-to-late 1800s building with fish scale exterior is near an industrial wonderland on North 6th. Both are just doors away from one of the hottest rock clubs in NYC, northsix.

Cork company building, North 7th; (right) diner sign, Bedford Avenue

A different fish scale house on North 5th has been individualized by its owner or a tenant.

Most homes in Greenpoint and Williamsburg, at least on the side streets, have been clad with aluminum siding. My favorites, like this one, haven’t.

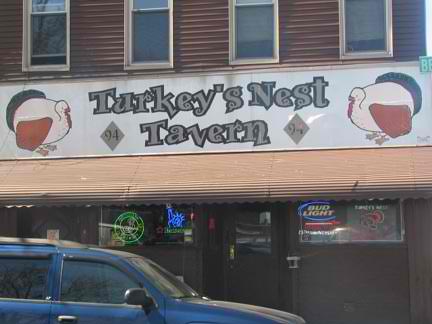

Turkey’s Nest, Bedford and North 12th, Williamsburg’s last dive, or one of the last. Your webmaster was drinking here one day when he ran into Ken Pomaski from school.

Turkey’s Nest, Bedford and North 12th, Williamsburg’s last dive, or one of the last. Your webmaster was drinking here one day when he ran into Ken Pomaski from school.

Who he hadn’t seen for 20 years.

Teddy’s Bar and Grill, Berry and North 8th Streets, has been here under one ownership or another since 1889; it was opened by the Peter Doelger family, whose name can still be seen in the stained-glass window. Teddy Prusik owned it in the 1980s, and his name is still there. One of Peter Doelger’s granddaughters was Mae West.

Teddy’s Bar and Grill, Berry and North 8th Streets, has been here under one ownership or another since 1889; it was opened by the Peter Doelger family, whose name can still be seen in the stained-glass window. Teddy Prusik owned it in the 1980s, and his name is still there. One of Peter Doelger’s granddaughters was Mae West.

Your webmaster once had a blind date here; she wasn’t much interested (what else is new) but Teddy’s was terrific.

Brooklyn’s, and Williamsburg’s, history is widely associated with the brewing industry as there were dozens here from the 19th Century through the late 20th; brewery barons built grand mansions along Bushwick Avenue. There’s still one here, though: Brooklyn Brewery on North 11th near Wythe. It’s been here since 1996 (and in business since 1989) and on Saturday, there are free tours, where you get free beer. I will repeat, free beer.

(I’m told that free beer has been canceled. Happy hour on Fridays has been added.)

We’re just getting started with Williamsburg; there’s just too much for one page and eventually, there will likely be three or four.

SOURCES:

Brooklyn By Name, Leonard Benardo and Jennifer Weiss, NYU Press 2006

BUY this book at Amazon.COM

Brooklyn’s Williamsburg(h), City Within a City, Brian Merlis, Brooklyn Editions/Israelowitz Publishing 2005

BUY this book at Amazon.COM

Photos taken throughout 2005; page completed July 29, 2006

©2006 Midnight Fish