CONTINUED FROM CREAKY ALLEYS PART 1

Before testing our courage and skulking around some more of lower Manhattan’s rare extant alleys, I thought we should pay tribute to a pair that are no longer with us….

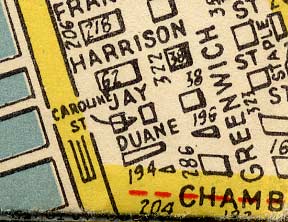

Caroline Street was a short lane running from Duane north to Jay between West and Washington. It was eliminated in 1970 when Independence Plaza and Manhattan Community College were planned for the site. The street is now covered by the school, which was finally completed in 1983; the campus’s Fiterman Hall was damaged on 9/11/01 and awaits rebuilding.

Curiously, Caroline Street formerly began at a small inlet called the Duane Street Basin and extended as far as Harrison Street. It was cut back to only one block by the mid-1800s, however, and was finally bulldozed in 1970. Map: Hagstrom, 1946

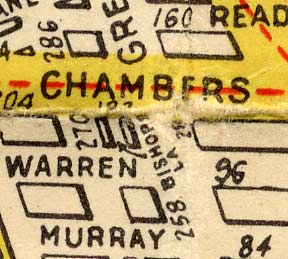

Bishops Lane was a one-block alley running from Warren north to Chambers just west of Greenwich Street. It, too, was eliminated about 1970 in the wholesale demolition of what was once theWashington Market area in favor of the massive World Trade Center and to its north, Independence Plaza.

1969 view of Bishops Lane (sliver at lower right) and Chambers Street (foreground) from Danny Lyon’s excellent Destruction Of Lower Manhattan, which chronicles the demolition of this lost Manhattan neighborhood from 1967-1970. The Woolworth Building presides over the scene.

The entire route of the former Bishops Lane is now completely covered by PS 234, which was built in 1988 by Richard Dattner.

The AIA Guide to NYC:

“A fanciful mix of eclectic architectural elements drawn in the architect’s imagination from the daydreams of kids who study here: watchtowers, sentry boxes, walled courtyards, arches from Historic Williamsburg, and Buck Rogers classroom wings.”

Now that we’ve waked the dead, let’s move on to the living, shall we. There are a couple other short lanes in Tribeca that look pretty much the same as they always have, and probably always will–as long as they are permitted to exist. When I first heard of them, several years ago, I thought both were named for household implements…Staple Street and Collister Street.

Staple Street

Staple Street, two blocks long from Duane north to Harrison just west of Hudson, turns up on maps as early as 1805, but when it received its name is unclear. Possibly, the name comes from the “staple” goods, such as wood or metals, traded in the vicinity. Long after the street was named, this part of Tribeca became a dairy “staple” center, with butter and egg wholesalers. It was originally a private road on which fronted blacksmithies and horseshoers that preferred to remain off the main routes.

Just as Saturn’s moon, Mimas, carries a crater that looks like it’s about a full eighth its size, and former planet and present planetoid Pluto has a moon, Charon, that is about half its size, so too does Staple Street boast a feature that is wildly disproportional to its modest two block length. I refer of course to the magnificent footbridge that crosses it north of Jay Street.

It’s a magnificent windowed arch that spans two brick buildings on each side of the street. As Oliver Allen explains inTales of Old Tribeca, the bridge dates to the early 1900s and in fact is a relic of a branch of New York Hospital.

In the early 1800s New York Hospital opened an emergency ambulance service at 160 Chambers, a couple of blocks south of here, known as the House of Relief. While NYH moved uptown twice (now it’s New York-Presbyterian at 1st Avenue and East 68th Street), it maintained the House of relief downtown and built a large building that can still be sen at 67 Hudson Street, as well as a separate building serving as a laundry (picture above). Both buildings were connected by the footbridge. A relic of NYH connection can be seen by the terra cotta shield on the laundry building…quite reminiscent of the Heins and LaFarge subway identification plaques that date from the same era!

In Tales of Old Tribeca Allen mentioned a fashion designer who made his home in 67 Hudson, now condominiums, who also had his offices in the old laundry building. His commute was a walk on the footbridge!

The famed footbridge isn’t Staple Street’s only architectural attraction. Once you pass under the bridge and head toward Harrison Street, ahead of you looms the Queen Anne-Romanesque New York Mercantile Exchange Building, built by Thomas Jackson in 1884.

“The Merc” began as The Butter and Cheese Exchange of New York in 1872 (note the two dates on the building) and in 1882 was already trading in excess of $100 million yearly in dairy produce when it expanded its purview to include groceries and foodstuffs of all types. The Merc began trading precious metals in the 1950s, and petroleum in the 1970s. It moved to the World Trade Center in 1976. Presently NYMEX operates from its headquarters in the World Financial Center where it is the world’s leading energy and precious metals trading exchange. The original building became home to condominiums in 1987.

Collister Street

A street very similar to Staple Street in length and width is Collister Street, which also similarly runs just west of Hudson Street for two blocks between Beach and Laight, crossing Hubert.

It is named after Thomas Collister, sexton of Trinity Church from 1793-1794 and again in 1797. Many, if not most, of the street names in the Lower West Side and Tribeca have a Trinity Church connection of some kind

There aren’t as many architectural highlights on Collister as there are on Staple, but there is this former American Express stables right), which I go on about on this ForgottenSlice page.

Franklin Place

While the rest of NYC is notoriously free of alleys (didn’t used to be, but the vast majority have been built on over the years) Tribeca stilll has a handful. Here’s picturesque Franklin Place, which runs for a block from Franklin Street north to White just west of Broadway. Most of NYC’s extant alleys began as service lanes or faced stables; I’m not sure what Franklin Place’s original purpose was, but we see that it unusually has smaller Belgian blocks than are used elsewhere in NYC, and, over the (at least) century and a half the alley has been here, the blocks have been worn down to the uneven consistency of cobblestones.

So who still uses floppies? Since I got my first IMac in 2002, I haven’t — either at home or at work. I use some software called Fetch to transfer files, or barring that, I use CD Rom disks. In a drawer somewhere I have some 5″ floppies, and somewhere else, a U-Matic videotape. You know what though, I still use a VCR and VHS tapes, and a cassette deck and tapes. At this point, it’s awkward to transfer this stuff to MP3’s, so I’m sticking with what I have there. I haven’t bought a CD for some time; I was getting new music from ITunes until I unsuccessfully attempted to install Tiger on my 2002 IMac last year (2006). Mistake. I haven’t been able to buy anything from ITunes since (with what my machine calls a keychain problem), which getting a new machine this fall should remedy, now that Apple has moved on to the new cat, Leopard. And Tiger in 2011! They’re running out of big cats.

Like Staple and Collister Streets, Franklin Place can boast a formidable building at its northern end. This, on White Street is one of Tribeca’s legion of cast-iron front buildings, which proudly advertises its completion date on its fleur-de-lis topped pediment. They won’t make ’em like this any more, kids!

At Franklin Street and Franklin Place, a rather unusual twin-bracketed wall lamp.

Walk down White Street and take a look at Civic Center Synagogue at 49 White, which is an avant garde creation that seems to mock its cast iron neighbors (it resembles a lightbulb cut in half), and then to 77 White, which used to be the Mudd Club: you will find a plaque there commemorating it.

Milligan Place

Moving north into Greenwich Village, we find a pair of odd lanes with a literary pedigree, Milligan and Patchin Places. In the mid-1800s a Samuel Milligan owned the property located at today’s 6th Avenue and West 10th Street, and built 4 townhouses surrounding a triangle-shaped plaza, to house Basque waiters at a 5th Avenue hotel. Eugene O’Neill once occupied one of them on Milligan Place.

Milligan Place is accessed from a usually locked gate on 6th Avenue; these two shots give you an idea how narrow. There’s a stenciled “Milligan Pl.” sign, and a wrought iron sign above the gate. The original access was from the now vanished Skinner Road, which was later straightened and became Christopher Street.

Patchin Place

Around the corner on West 10th Street, we find the cul-de-sac known as Patchin Place, named for Samuel Milligan’s surveyor, Aaron Patchin, who some say became his son-in-law. It actually predates Milligan Place by a couple of years, and its homes were originally worker housing, as was Milligan’s.

Patchin Place also became a literary enclave of sorts, and at various times was home to e.e.cummings (#4, at left), as well as Theodore Dreiser and Djuna Barnes

MacDougal Alley

MacDougal Alley, a cul de sac off its namesake steet just off West 8th Street, was built in the mid-1800s as a mews serving the well-to-do homes along Washington Square Park North, which is just a block to the south. The term “mews” refers to a short lane where horses are stabled. Sebastian Deckker, in his excellent Mews Style that describes many of London’s attractive mewses, describes the word’s origin:

The term “mews” first appears in connection with the Royal Mews when it was originally situated at Charing Cross…This was where the royal falcons were formally “mewed” or left to shed their plumage. After a fire in 1537 destroyed his stables in Bloomsbury, Henry VIII turned the Royal Mews into the Royal Stables. The birds were evicted and, after some enlargement and reorganisation, the horses, together with the itinerant stable staff and grooms, were installed in their new residence. This new generic term of stables and coach-houses being referred to as “mews” came to be known in the seventeenth century, increasing in popularity for the next two hundred and fifty years.

MacDougal Street and Alley take their names from General Alexander MacDougal (1733-1786) a founder of the Sons of Liberty and first president of the Bank of New York.

MacDougal Alley has been home to fashionable residences for over a century. Prior to that it had been called a “dirty, foul-smelling court,” given over to “back-alley gamblers and the rougher element.” Sculptor Philip Triebel restored a stable in the mews for a private residence, and began a trend that has radiated to other short Greenwich Village lanes.

Around 1902, he leased 6 MacDougal Alley, installed skylights and a giant north window, and moved in with his family. The Sun called it “the most unique studio in town,” filled with artifacts and lit by a skylight latticed “in the old mission style.”

Triebel talked up the idea and was soon joined by Henry Kirke Bush-Brown, Daniel Chester French, James E. Fraser and other sculptors and artists. In 1906, The Craftsman magazine noted the cozy, familial air that still distinguishes the little Greenwich Village street: “in the summertime the doors of the studios are thrown open, and the artists’ wives take their chairs on the clean, cemented court, while the children play in perfect safety around them.” Christopher Gray, NYTimes, December 11, 1994

Washington Mews

Washington Mews, the only such lane in NYC officially known as a “mews,” once served the same purpose MacDougal Alley did: to access stables of dwellings along Washington Square Park North. The Belgian-blocked lane shares a history with Sailors Sung Harbor in Staten Island: it was once part of Captain Richard Randall’s farm. When the heirless Randall left the home to the City on the proviso that it a home for elderly and/or disabled sailors be built there, the city found the parcel too small for that purpose, and purchased farmland in northern Staten Island where the enclave, now a museum, exists today. The city leased Randall’s original farm and used the proceeds to build the Staten Island complex, which opened in 1833. The stables were replaced by dwellings by the late 1910s, when the auto displaced Dobbin as the city’s primary means of transport. Over the years, the stables served the families of tobacco magnate Pierre Lorillard and later, residences were occupied by sculptor Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney and your webmaster’s favorite painter, Edward Hopper. You can find it between 5th Avenue and university Place just north of Washington Square Park.

Beginning in 1916 architects Maynicke & Franke added stucco and decorative tiles, some of which remains today.

RIGHT: Looking toward 5th Avenue we see #1 Fifth Avenue, at 29 stories the tallest building in Greenwich Village. It was built in 1929 by architects Helmle & Corbett with Sugarman & Berger. For many years, a restaurant on the first floor, also called One Fifth Avenue, was decorated with Art Deco remnants rescued from the Cunard Liner SS Caronia.

Grove Court

An old property line in the West Village causes three streets, Grove, Barrow and Morton, to make midblock curves. Along Grove Street’s bend, you will find a surprise: a gated enclave conatining several ivied, red-bricked buildings called Grove Court.

The alley was built between 1848 and 1852 by Samuel Cocks, a grocer at 18 Grove, who decided to build housing for tradesmen and laborers that would make excellent customers for his grocery. In fact one of the old names for Grove Court was Mixed Ale Alley.

Picturesque Grove Court was the setting for O. Henry’s story “The Last Leaf” about an ailing young woman and a failing artist. It was filmed for the 1952 movie O. Henry’s Full House.

In 1999 I was let in by a resident and got rare views, for nonresidents, in front of one of the townhouses.

Grove Court is not the only example of hidden “back houses” in the Village. They are rather common in the neighborhood but their existence is known to few but their owners, who access them via extremely narrow passages.

Few New York residents know the location of its hidden houses better than Patricia Mason, (then) vice president of the William B. May Company, the real estate firm. When asked to define the special quality of hidden houses, Mrs. Mason said, ”The most astonishing thing about them is that you cannot imagine them until you have seen them.”

She likes to take people to her own house on Morton Street. Next door is an exceptionally fine Greek Revival dwelling of three stories above a high English basement. To its right is an iron gate. From her garden there is a view of two handsome brick houses standing side by side. Completely shielded from the street, they inhabit an island of trees, shrubs and flowers. Indeed one cannot imagine them until one has seen them.

In his superb essay, ”Here is New York,” E.B. White wrote: ”On any person who desires such queer prizes, New York will bestow the gift of loneliness and the gift of privacy.” For those living in its hidden houses, the gift is always the latter one. David Lowe, NYTimes, September 17, 1981

Extra Place

Extra Place, on East 1st Street just east of the Bowery, has existed in one form or another since about 1800, when landowner Philip Minthorne divided his 110-acre farm equally among his four sons and five daughters. A tiny parcel was left over, which became Extra Place.

Developers Avalon Chrystie LES, who have already created many large new residences in the East Village along the Bowery and its side streets, according to Curbed“hopes to transform a long-neglected alleyway called Extra Place into ‘a slice of the Left Bank, a pedestrian mall lined with interesting boutiques and cafes.'”

(RIGHT) a look at Extra Place in 1978. At one time the alley led to the back door of Hilly Kristal’s CBGB, which fronted at Bowery and Bleecker. The club closed in 2006, and Kristal passed away the following year. Bob Mulero

Freeman Alley

It is, perhaps, Manhattan’s narrowest dead-end and until a few years ago, the borough’s most unknown alley. Yet in recent years, Freeman Alley, on Rivington between Bowery and Chrystie Street whose presence was all but unsuspected for years, has become a hotbed of sorts. The name may be derived from early 19th Century surveyor Uzal Freeman, who lived in the vicinity and perhaps may have laid it out.

It’s just a crack between buildings, really. But a reward of sorts await those who follow it all the way to the end, about the length of a football field.

Down a dark, shadowy alley just off Bowery, the handsome, scruffy-faced men and understatedly glamorous women of the Lower East Side gather to drink wine, crowding around antique wood tables. Worn plank floors and painted cement walls, fit with moose, elk and other assorted taxidermy, give the place a quirky edge, as do the tattooed, waifish servers, who are also professional and expedient. NYC Search

The place is called, quite logically, Freeman’s and like Chumley’s, is unmarked, since it doesn’t need to be. Freeman’s once apparently refused admittance to President Bush’s twin daughters.

At Rivington and Freeman we find Freemans Sporting Club, a combined haberdasher and barber (you read that right). It is a creation of Freeman’s founders.

As Freeman Alley has become more trafficked it has attracted a number of street artists. Whose “pieces” are these?

photographed August 2007; page completed October 28, 2007