October 4, 1969. The Mets beat the Atlanta Braves in Atlanta 9-5, beginning a ‘miraculous’ postseason run for the Amazin’s in which they won 7 of 8 games against the NL West Champion Braves and AL Champion Baltimore Orioles, winning the World Series. While the USA had put two astronauts on the moon in July, the war in Vietnam continued to drag on with no resolution in sight. Incumbent NYC mayor John Lindsay, running as an independent, faced an uphill battle against Democratic and Republican opponents. It was also the day that the 81-year-old Myrtle Avenue El ended service.

The Swingin’ Sixties, and the Fab Fifties, for that matter, saw a gradual decline in the NYC transit system after ridership peaks in the 1940s. The system would continue a slide into dangerous conditions, with overall deterioration increasing and burgeoning crime. It seemed the city was giving up on mass transit as more and more els shut down and no new subway lines were built to replace them; by 1969 all of Manhattan’s great el trunk lines, the 2nd, 3rd, 6th and 9th Avenue els, had long disappeared.

The Transit Authority wasn’t done eliminating els, either; the demise of the Myrtle was soon followed by the razing of the last vestige of the Third Avenue El in the Bronx in 1973; the Culver Shuttle (really the northern end of the Culver El, the line’s connector to Brooklyn’s old Fifth Avenue El) in 1975; and the eastern end of the Jamaica el (the eastern end of Brooklyn’s Broadway el) in 1978; replacement service to Parsons Blvd. and Archer Avenue would not begin until a decade later. The 2nd and 3rd Avenue Els were never replaced; Myrtle Avenue service was paralelled, but never really duplicated, by the IND GG train and the B54 bus.

In its original incarnation, opening to fares on April 10, 1888 the Myrtle Avenue el ran from Johnson and Adams Streets downtown south and then east along Myrtle Avenue to Grand Avenue, south to Brooklyn’s Lexington Avenue, then east to Brooklyn’s Broadway, joining the Broadway el there. Later that year, on September 1st, the Myrtle was extended west to a Washington Street terminal adjoining the Brooklyn Bridge. Connections to Manhattan were made on June 18th, 1898 when the line crossed the Brooklyn Bridge (along with Brooklyn’s 5th Avenue El line) to a Park Row terminal. The Brooklyn Bridge crossing remained in service until March 5, 1944.

On its eastern end, the Myrtle Avenue el was extended along Myrtle Avenue from Lexington Avenue to the Broadway el on April 27, 1889. Further extensions were later made to Wyckoff Avenue and the line attained its greatest length when an extension was made to Lutheran (now All Faiths) Cemetery on Metropolitan Avenue in 1906, annexing an old surface steam railroad line. That stretch was converted to an el under the Dual Contracts arrangement in 1915 along a separate right of way, a common arrangement in other cities (especially Chicago) but rare in NYC.

The Lex

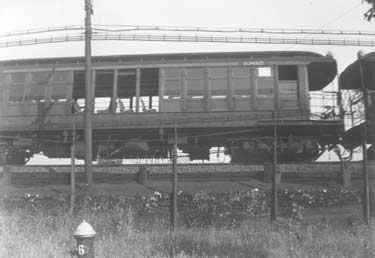

The Myrtle was not the first el in Brooklyn. That honor goes to the Lexington Avenue el, which ran from Fulton Ferry to East New York, opening in 1885 and running along Lexington Avenue in Bedford-Stuyvesant for its entire length until the line was closed in October 1950. The Lex has a fascinating and complicated history. Above left, from the 1930s or 40s, a photo of one of the gated wooden cars the line employed.NYCSubway.org

RIGHT: amazingly some of the support pillars for the old Lex are still in place at the NE corner of Grand and Lexington Avenues, where the line made an L-turn. The pillars are embedded in a brick building likely constructed just after the el was torn down.

![]() This Hagstrom NYC transit map produced in 1956 shows the Myrtle as it was between March 5, 1944, when Brooklyn Bridge service was eliminated, to October 4, 1969. The line’s western terminal was Bridge-Jay, where a transfer to the IND Jay Street station (today, A,C and F trains stop there) was available. The eastern terminal, then as now, was Metropolitan Avenue.

This Hagstrom NYC transit map produced in 1956 shows the Myrtle as it was between March 5, 1944, when Brooklyn Bridge service was eliminated, to October 4, 1969. The line’s western terminal was Bridge-Jay, where a transfer to the IND Jay Street station (today, A,C and F trains stop there) was available. The eastern terminal, then as now, was Metropolitan Avenue.

It’s interesting to note that when all BMT routes got letter designations in 1967, the Myrtle received MJ (for Myrtle-Jay). However the Q-Type el cars running on the line were unable to display roll signs, so the cars were never so marked. A further refinement in BMT-IND nomenclature eliminated two-letter names in 1978.

By 1953 the stops on the Myrtle were: Bridge-Jay, Navy Street, Vanderbilt, Washington, Franklin, Nostrand, Tompkins, Sumner, Broadway, Central, Knickerbocker, Wyckoff, Seneca, Forest, Fresh Pond Road, and Metrropolitan Avenues. A Grand Avenue stop (between Washington and Franklin) was closed in 1953, likely as a result of the razing of the old Lex el. After 1969, all stops west of Broadway were eliminated.

The Myrtle lives on between Broadway and Metropolitan Avenue. A connection was made between the Broadway and Myrtle els in July 1914, enabling Myrtle el trains to enter Manhattan via the Williamsburg Bridge; this is essentially the route the M train follows today. Unusually, the connection is not a flying junction in which the cross track is bridged over; the tracks merely cross atop the el, quite rare in the NYC transit system. Myrtle Avenue continues to be enshrouded between Broadway and Wyckoff Avenue, where a transfer is available to the Canarsie BMT (L train).

The Q-Types

The Q-Types, so called because they were previously used on the Flushing Line from Queensboro Plaza to the World’s Fair in 1939, were the line’s workhorses from mid-1958 through the end of service in 1969. They replaced gated cars, which had run on the 5th Avenue El, Culver El and Lex El; some went back to as early as 1906! The Qs were the last cars whose bodies were wooden and the last cars in the NYC transit system that had once used gated car platforms. The Myrtle el west of Broadway had never been reinforced to allow steel cars to run on it, as was mandated during the Dual Contracts.photos: Times Newsweekly, where you can read more info about the Q-types

The Q-Types transferred to the Myrtle were originally gated as well (above left). They underwent considerable modifications for their Flushing Line run, with the end gates and side panels removed. Ceiling fans were still used in this era of no transit sytem air conditioning.

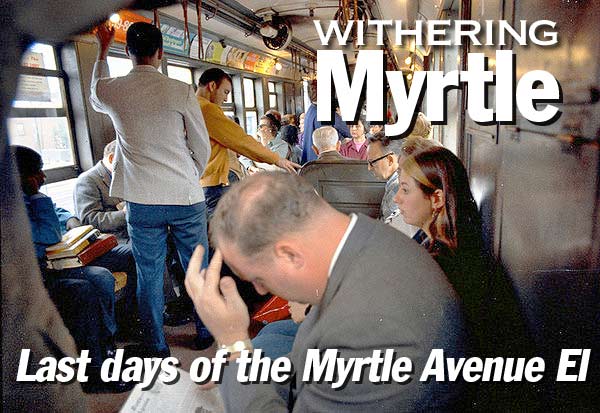

Evening rush hour on the Myrtle El, 1969. Most of these folks are headed to NE Brooklyn or SW Queens and have likely transferred at Jay Street from IND trains originating in Manhattan.

The “thank you” sign on the window at right likely refers to the imminent shutdown of the line. To get home, many of these people will have to use the then-GG IND Crosstown Local through Fort Greene, Bed-Stuy and Greenpoint, or use the Nassau Street local (J,M) over the Williamsburg Bridge.

Note the zip code ad upper right. Zips had been introduced in the early 1960s, but they were enough of a novelty that the Post Office was still urging their use in 1969. I can’t seem to make out the rest of the ads.

Note that with this seating arrangement, passengers faced each other in close quarters, handy when people entered in 2s, 3s and 4s, but otherwise, the no-eye contact rule applied!

Your webmaster is far, far away from a fashion maven (except when it comes to Forgotten NY apparel) but the three ladies on the right approximated my mother’s look at the time, and they’re likely in their low 50s. Women in their low 50s, at least many of them, look a lot younger than that these days. Many of the men wear topcoats, jackets, ties and hats, though hats had begun to be absent from heads increasingly in the 1960s. By the end of the Super 70s, most hats that men wore were toques in the winter and baseball caps other times of year. Before this, ah, heads off to an uninformed fashion tangent, we’ll get back to the el….

Nearly empty Q-type in the final days of its Myrtle career. Some Qs can still be found at the MTA Transit Museum in Brooklyn. In 1969, graffiti was not yet a big factor on the trains, but vandalism certainly was; by this time most lines, with a couple exceptions, had switched to cars with plastic benches. The wicker and foam seats seen here were regularly attacked by switchblade-armed malcontents.

Heating units under the seats got quite warm indeed, which was quite welcome on those winter days when cold wind gusts invaded the trains when the doors opened. I don’t know if the Myrtle retained the potbelly stoves other el lines had by 1969.

Along the Myrtle El

Let’s make one more run along the Myrtle El with a fantastic set of photos graciously allowed to appear on FNY by ForgottenFan Pat Cullinan Jr., from his personal collection…some scenes here are of a Myrtle Avenue that is long gone…

No shortage of bars and liquor stores along Myrtle Avenue; there are two in this shot alone.

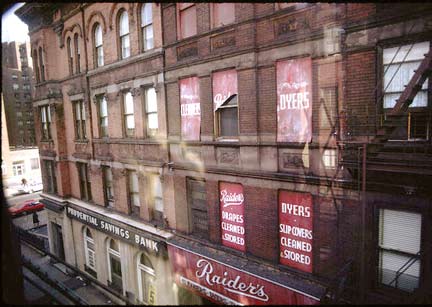

Plenty of buildings adjoining the el had painted signs to attract the captive audience.

NY Telephone Building, 101 Willoughby Street

When the trains rumble past, make sure you’re not doing anything you don’t want people to see.

Venezia & Sons Firestone service station. That’s a scene from a classic sculpture or painting, no? Forgotten Fans, help me out, again.

ForgottenFan Paul Gianakos: The statue atop the Venezia Tire Company is taken from the old Fisk Tire Company ads that ran in the 1920s, 30s, and on up probably. They show a sleepy little boy in his sleeper holding a candlestick in one hand and a tire slung over one shoulder. The ad copy says: “Time to re-tire.”

Very clever. Fisk is still in business and I am running a set of them on one of my cars. No complaints.

In 1917 the Fisk Tire Company of Chicopee Falls, Massachusetts, challenged Norman Rockwell to do a series of advertising paintings for Fisk Tires. The company was producing rubber tires for automobiles and bycicles and did extensive advertising in several magazines. The slogan “Time to re-tire” was very popular and caught the fancy of Mr. Rockwells sense of humor. The series that he did for the Fisk Company was among the most popular. The Fisk Bicycle Tire advertisements appeared in American Boy from 1817 to 1919. The company started a bicycle club which was extremely popular among young boys, and Mr. Rockwell’s ad of kids on bikes increased in its popularity. chuquimata

Fisk was purchased by Uniroyal, and what a rival symbol was doing here is unclear!

The Myrtle Avenue El predated the Flatbush Avenue Extension by nearly 20 years; the extension was built in 1909, connecting the new Manhattan Bridge to Flatbush Avenue, which until then originated at the intersection of Fulton and Nevins Streets. To accommodate the 6-lane boulevard, the Myrtle El was placed on a steel viaduct that spanned the new road so traffic would not be impeded by pillars. In the Brooklyn Eagle photo above, taken in the Roaring 20s, many of the buildings have vanished from the current scene…except for the clock tower at right on Gold Street, still in use today as a warehouse.

In 1969, we see the clock tower still holding forth. It has undergone a lot of paint jobs since then, including a bright yellow version in the 1980s. The Howard Clothes neon sign further up Flatbush has lost all its letters but one.

Flatbush Extension looking south. When I visited the same corner 30 years later (below) I found a sign for an Oldsmobile dealer still there. The sign and the building it was on have since been razed. In BOTH pictures, “Goetz” is a ghost ad!

One thing you notice in these nearly 40-year-old pictures is that cars, and not just Olds, looked like boxes on wheels then.

Church of St. Michael and St. Edward (one saint per tower, supposes your webmaster), St. Edwards Street north of Myrtle, was built in 1902 by architect John Deery as St. Edward Church. Its claim to fame regarding the Myrtle Avenue El is that you can still see the el when you enter! The church replaced its altar in 1972 with a new one built with a few of the old girders spared when the Myrtle Avenue El was demolished.

Fort Greene Park. From the Forgottenbook: Fort Greene Park forms a 30-acre quadrilateral of green between DeKalb and Myrtle Avenues on the north and south, St. Edward Street and Brooklyn Hospital on the west, and Washington Park on the east. It is named for a fort built in 1776 at what is now the park’s central summit by General Nathaniel Greene (1742-1786). The fort, originally named Ft. Putnam, aided in George Washington’s retreat after his defeat in the Battle of Brooklyn in 1776, and was reactivated during 1812 when a British attack was anticipated.

Walt Whitman, editing the Brooklyn Daily Eagle from 1846 to 1848, pressed for a public park in the area, and in 1847, Washington Park, named for the President, began development. Whitman lived nearby, at 99 Ryerson Street in a building that is still standing, and it’s not surprising he wanted a park near his home.

Washington Park was designed by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, the architects who went on to develop Central and Prospect Parks. It was officially opened in 1850; in 1897 the park was renamed for Fort Greene. By then the area had become a handsome residential neighborhood. The two-block stretch of Cumberland Street lining Fort Greene Park’s eastern side is still called Washington Park.

During the Revolutionary War, the British anchored eleven prison ships in Wallabout Bay (the body of water west of Williamsburg) and subjected American prisoners of war to deprivations and torture during the years 1776-1783. More than 11,000 died in the ships.

There were early monuments to those who became known as the “prison ship martyrs”: some of the remains were buried in the vicinity of the Navy Yard in 1808 and interred in Washington Park in 1873. The current monument, a 148-ft. Doric column, was designed by McKim, Mead and White (the firm that would later design Pennsylvania Station) and dedicated by William Howard Taft, then President Teddy Roosevelt’s Secretary of War, in 1908. The monument originally featured a staircase and elevator to its summit, where there was a lighted brasier and observation deck. The elevator was broken by the 1930s and was finally removed in the 1970s. The Prison Ship Martyrs Monument, however, remains one of Brooklyn’s more striking landmarks, visible from any part of the neighborhood. The remains of the prison ship martyrs are interred under the monument.

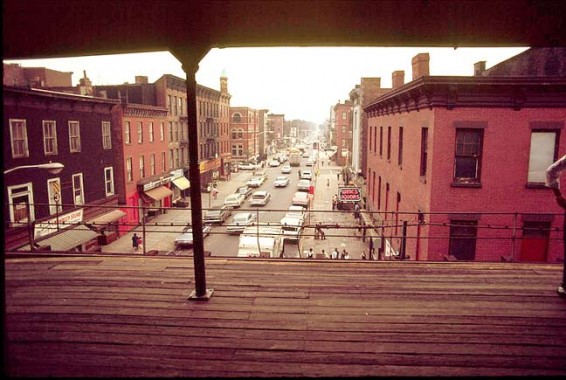

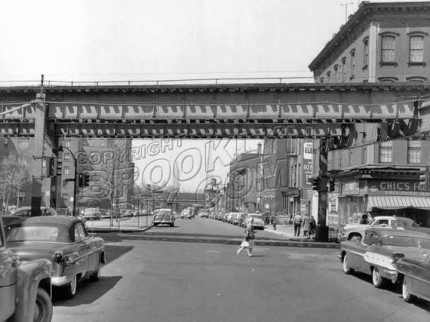

Under the El. We are looking west along Myrtle Avenue some time after 1944 (that year the Raymond Ingersoll Houses, right, were built). Everything on the left side of the photo was torn down when the University Towers Houses were built some years later. The trolley tracks were used by trolley lines #15 and #54, with the #15 accessing via Navy Street (left). Both lines were out of business and replaced by buses by 1951.Brooklynpix.com

Under the El. We are looking west along Myrtle Avenue some time after 1944 (that year the Raymond Ingersoll Houses, right, were built). Everything on the left side of the photo was torn down when the University Towers Houses were built some years later. The trolley tracks were used by trolley lines #15 and #54, with the #15 accessing via Navy Street (left). Both lines were out of business and replaced by buses by 1951.Brooklynpix.com

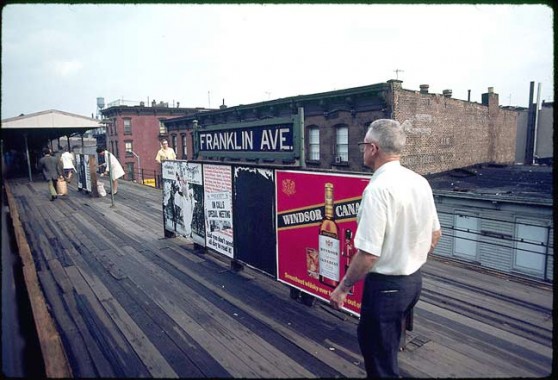

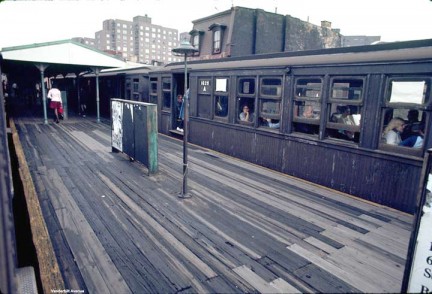

Above and below, Franklin Avenue station area, 1969. Till the end of service, the Myrtle el retained its wood plank station platforms and station signs with white lettering on blue enamel.

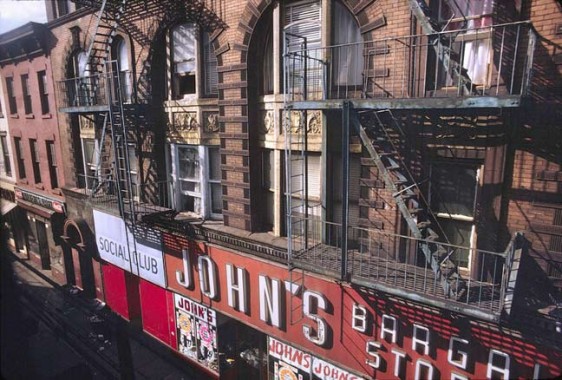

John’s Bargain Store — with its big red sign and white lettering — was once a nearly ubiquitous presence in the New York metropolitan area, particularly in low-income sections. It grazed the low end of retailing, relying on paying cheap rent for locations few other retailers wanted, as well as on buying merchandise that could be startlingly inexpensive, often because the manufacturer had overestimated demand.

”Give us your mistakes and we’ll make them pay,” was a company slogan. A company maxim was that the best places for stores were areas with few new automobiles but many used baby strollers.

At its peak in the mid-1960’s, John’s had 527 stores along the Eastern Seaboard and in Puerto Rico.

”Our plan is to blanket the United States with John’s units and to ultimately have more stores in operation in this country than Woolworth’s,” Mr. Cohen said in an interview with Women’s Wear Daily in 1964.

A Woolworth spokesman had said, ”We wish them luck.” [Full story, New York Times, 2002]

From the platform, looking south. Note at far left on the 2nd photo: a ghost ad for Quaker Oats.

Looking north at Nostrand Avenue (above) and Tompkins Avenue (below)

Carlton Avenue crosses Myrtle Avenue, early 1960s. The Walt Whitman Houses can be seen at left.Brooklynpix.com

When the announcement came that the Myrtle was shutting down, photographers began to populate the platforms. Tripods are verboten in the trains these days, and all subway photographers are regarded with suspicion by the MTA and NYPD.

LEFT: Note the ad for Mario Procaccino (1912-1995). He was the Democratic candidate for mayor in the 1969 election; Staten Island’s John Marchi defeated incumbent mayor John Lindsay in the Republican primary. But the major party candidates split the vote, allowing Lindsay to obtain a second term. Marchi went on to complete 50 years in elected office (matching Emanuel Celler‘s record, but I’m dating myself), retiring in 2006.

Raider’s Dyers

Renken’s Milk plant, Classon Avenue

The Renken’s buildings are still there at Myrtle Avenue, Emerson Place, and Classon Avenue. above and right: Gary Fonville

In 1912 Martin Renken of the M.H. Renken dairy companybought the whole block, and in 1923, constructed a bank of industrial loft buildings along Classon that became 202, 204, 206 and 208 respectively. The buildings haven’t been fundamentally changed since they were first designed and built by Brooklyn architecture firm Koch and Wagner, all yellow brick and wood shutters and windows that don’t open.

While the upper floors were used for pasteurization and bottling, the ground floor of 206 was used as a stable for horse-drawn carriages; a few years later, the stable was converted into a loading dock. The Classon buildings were one section of a three-part complex that also included 131-137 Emerson Place, built in 1924, and the main office at 574 Myrtle Avenue, built in 1918. Susie Cagle

What will happen with the Renken Dairy? Luxury apartments. Why even ask?

Here’s one of the ancient Q cars, 1625A to be precise, awaiting the signal to proceed at the Vanderbilt Avenue station. It was pretty warm out, and on those cars you could open the windows. Once again, the platform was splintering wooden planks and it was illuminated at night by sparse incandescent bulbs (the ones not broken, that is.)

Interesting tableau here, with what must have been a country house now surrounded by 3-story taxpayers. There’s a Cadet Dog Food sign (and yes, dog food was still called Dog Food back in 1969) a clip joint in the literal sense, and a little girl in a red coat. This reminds me of a scene in Schindler’s List, but I hope this little girl is alive and well these days.

What remains

Not a whole lot, though an entire disused section can be found atop the Broadway-Myrtle station (J, L and M trains.)

Myrtle Avenue, looking east from Flatbush Avenue Extension

The el once rattled past Cascade Laundry, Myrtle and Marcy Avenues

These buildings, certain to be razed if they haven’t already been, date to the days of the el. South side of Myrtle east of Flatbush.

An unused section of the el still covers Myrtle Avenue from Broadway west to Lewis Avenue. Hang around long enough and you might hear the echo of a passing train, or a platform conversation.

Joe Testagrose Myrtle Avenue El album

Flatbush Avenue Myrtle Avenue El Trestle comes down

1969 video of the last days of el service:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eDxFyLIlvi4#t=1886

Page completed December 9, 2007

©2007 FNY