Despite the fact that ForgottenTours 24 (in April 2006) and 29 (in April 2007) have taken place in Green-Wood Cemetery (and there are likely more tours upcoming) I have yet to write a definitive FNY page on the vast enclave, probably because it would take multiple pages to do it justice — the sheer details, combined with the interesting and unusual personages entombed here, make it a fairly daunting task. I myself would love to wind up here but the plots are going for over $5000 these days. Of course you would be there for hundreds of years until NYC is finally under water, or Putin or one of his successors attacks, or something.

For years, Green-Wood Cemetery was called just plain Greenwood Cemetery, on most maps, anyway, and though officially, it’s always been Green-Wood, the hyphen has begun to make more inroads of late. I think old-fashioned spellings are fairly pretentious — no-one spells “to-day” or “to-morrow” anymore, except for effect. I suppose, though, that Green-Wood, which turns 170 years old in 2008, has earned the right to spell its name any way they want. In fact, on their website, it’s “The Green-Wood Cemetery,” thank you.

When in the cemetery, wander the hills and meandering roads and sit by the still ponds where benches are provided. The cemetery has heavily wooded regions, and wide-open plains where the wind can howl on fall and winter days. There are many hills, but none that will be exhausting to climb. Mausoleums hold a particular interest for me: if you stroll up and peer through the window that often appears in a mausoleum door, you will often observe a small, exquisitely-designed stained glass window with, more often than not, a religious theme.

Today I wasn’t going into Green-Wood, even though Richard Upjohn’s massive brownstone arch at the main gate at 5th Avenue and 25th Streetwith its massive carvings depicting Biblical scenes and its nests of squawking parrots beckon anyone who wanders past.

No. Today, on one of the hottest days in July, I am instead going to walk all around the cemetery without going in.

Why circumnavigate Green-Wood? I wanted to see the neighborhoods that touch on it, note their similarities, note their differences and see how the cemetery’s presence has affected them. I like it that Greenwood Heights, Sunset Park, Borough Park, Kensington, Windsor Terrace, and Park Slope, despite being disparate, far-flung neighborhoods, all can claim Green-Wood Cemetery as their own (I am similarly fascinated by the fact that two states, Missouri and Tennessee, border on eight others; Green-Wood is the Missouri or Tennessee of Brooklyn.)

So here we begin at 5th Avenue and 25th, the cemetery’s main entrance. Green-Wood was Brooklyn’s first major public recreational space, opening to the public in 1842 (Prospect Park would not follow until 1867) and as such, it used to be a major transportation hub. A horsecar line instituted by Charles Gunther began service from here to Bath Beach Junction in 1864 — and after conversion to steam railroads, electric railroads and finally elevated service, it’s today’s BMT West End Line, currently plied by the D and M trains.

At present 5th Avenue, which runs along Green-Wood’s western flank from 24th to 36th Streets, is being torn up and new sewer pipes put in. The sight of this gave me a slight hint of nostalgia as I recalled 5th Avenue was similarly torn up along the route of the B63 bus during my high school years in the Super 70s.

We already have a building of historic importance and beauty right off the bat, at 5th and 25th — the McGovern-Weir Florist greenhouse. James Weir opened the floral business with plant nurseries and greenhouses in the Yellow Hook in what is now Bay Ridge in the 1850s. After a yellow fever epidemic struck the area, taking a heavy toll, Weir proposed renaming Yellow Hook as Bay Ridge, since it was built along a hill facing Upper New York Bay. The region formally approved the name change in 1853. According to legend, the Weir greenhouse, sporting a wrought-iron “Weir” at the top (with the added-on McGovern latter-day partner’s name) originally appeared in the St. Louis, MO World’s Fair in 1904. 40 years later, Vicente Minnelli directed his future wife Judy Garland in the movie musical set at the fair, Meet Me In St. Louis, much remembered for the melancholy hit “Have Yourself a Merry Little Christmas.”

Yale Frames and the Staplex Company (777 5th Avenue) were staples of your webmaster’s view out the B63 windows as the GM fishbowl buses rattled down 5th Avenue in the 1970s, and they’re still there today. As you’d probably expect Staplex makes automatic electric staplers but also high volume, asbestos & lead air sampling equipment

Continuing south along 5th Avenue, on either side of 30th Street opposite the cemetery we see the back yards of a group of homes, seemingly turned away from the cemetery as if fearing it. These are a pair of private courts named Woodrow (the south side of 30th) and Roosevelt (the north side). A little bird told me (and I’ll try to get the link later) that the two courts were constructed in 1922 and the homes originally sold for between $6,950 and $7,500. What’s that in today’s money?

Learning that they were built in 1922 solved one mystery — Roosevelt Court is named for Teddy, though FDR was already well-known, since he was by 1922 a New York State Senator, Secretary of the Navy, and had run unsucessfully for Vice-President in 1920 as James Cox’s running mate, losing to the Warren G. Harding – Calvin Coolidge ticket.

A remaining mystery is why Woodrow Court is so-called; why not Wilson Court? There was not previously a Wilson Court on the Brooklyn atlas.

Though Greenwood-Heightsers have attempted to change the zoning to beat the developers, high-rise buildings have begun to sprout along Green-Wood Cemetery’s western and northern edges. Oddly, the terraces on the Fedders Special-writ-large on the right face up and down 5th Avenue, instead of the eastern view…

…which provides a fine view of the cemetery’s Sylvan Water along with one of the hillier vistas, scattered with monuments and mausolea.

At 5th Avenue and 32nd Street we see one of the previous generation of NYC bus shelters. There has always been an emphasis on glass on these things. The glass attracts miscreants the way grandma pizza attracts your webmaster. At left, the Hopper-esque scene (except, of course, for the honkin’ gas-guzzler in the front yard) shows some old two-story brick apartment units, comparable in age to Roosevelt and Woodrow Courts.

5th Avenue runs over two bridges — one here, over a cemetery entrance road that begins at 4th Avenue and 34th Street, and the other over the Long Island Rail Road Bay Ridge Branch and the Sea Beach (N train) tracks south of 64th Street.

Union Depot

So, which building do you like better? The present-day Jackie Gleason Bus Depot, built in 1988, or the structure it replaced, the 1890 Union Depot, which served the Brooklyn, Bath and West End Railroad (today’s D and M trains) and the Culver (today’s F train)? I thought so.

The Union Depot became a subway/el car and bus inspection shop in about 1917 and served that role until 1984, when it was demolished. The much sparer Jackie Gleason Depot was built in 1988, named for the Brooklyn comic whose perhaps most beloved character was Brooklyn Bus driver Ralph Kramden.

Union Depot photos: Art Huneke

The Gleason, one of the major depots in NYC, serves the B8, B9, B11, B16, B23, B35, B37, B61, B63, B65, B67, B68, B69, B70, B71, B75 and B77 lines, serving western and central Brooklyn from Bay Ridge to Crown Heights. There is also a small museum fleet including a 1948 GM and 1956 Mack — the green and white buses I rode on in my youth.

Turning southeast now along 36th Street see see a large mausoleum in the distance belonging to a W. Syms.

The Cemetery has an incredibly lengthy fence running along its entire exterior, and all the fenceposts bear this motif I call the Cabbageheads, since the ornaments resemble that vegetable. Most of the fence is black; this is likely a primary coat.

The 36th-38th Street Subway Yard (the entrance gate seen here above right) is primarily used for storage and maintenance of work trains and non-revenue service vehicles (The Coney Island Yards, further south, is one of the largest subway car maintenance sheds in the world.)

It is also a former trolley car barn, and we see a remaining trolley pole here on 36th Street, now used as a signpost. 39th Street was formerly a major trolley route, as many lines converged on the Brooklyn waterfront bringing workers to maritime concerns there, as well as ferries to Manhattan.

To walk around Green-Wood Cemetery you take a brief zigzag down a one-block stretch of 7th Avenue, which puts in a cameo appearance here and is in fact built on an overpass over the 36th-38th Street Yard.

The Cemetery itself is the fortunate byproduct of a national finanicial panic (if not outright depression) in 1837, when real estate prices dropped dramatically. That made parcels of land in Kings County much more affordable and plots owned by longstanding county families such as the Wyckoffs, Deans, Sacketts, Schermerhorns, and Bergens, whose names survive today on Brooklyn street signs, were purchased by the City of Brooklyn, which had the later task of wrangling a new street grid around its borders. Therefore, as we’ll see, the Cemetery has a very irregular boundary — think of the Fenway Park outfield, which has to bend and curve to the will of the Back Bay street layout.

The Cemetery continues along 37th Street from 7th Avenue to Fort Hamilton Parkway — an isolated stretch and a main auto toute as a chief connector between Sunset Park and Borough Park in this area. 37th Street is also isolated by the presence of the BMT yard on its southern flank.

Glimpsed behind the heavily barbed-wired security fence of the BMT Yard (vandalism would follow as night follows day if the protections were not there) we can see a pair of former R33 World’s Fair IRT cars now devoted to maintenance work: Car No. 9340, still bearing its old Redbird plumage, and Car No. 9038, now canary yellow in its new role as work car No. RD428. [Here it is at the Coney Island Yards complex.]

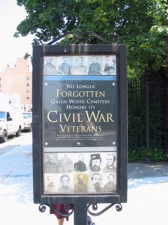

Meanwhile we continue to roll past Green-Wood, and past the distinctive marker of war veteran Charles John Kostenbader.

A plant bearing large pods (Forgotten horticulturalists, fill me in here) as well as a couple bottles of Merlot in the grass. Good thing Miles Raymond isn’t here.

Wisteria, I’m told. Don’t eat the pods.

A Slight Detour

9th Avenue is the only street that 37th Street encounters between 7th Avenue and Fort Hamilton Parkway, and since there are a couple interesting items here I made a one-block detour to Heffernan Square, actually a triangle where 9th Avenue, New Utrecht Avenue, and 39th Street meet.

The stretch seen above left is the only sun-splashed stretch of New Utrecht Avenue, since the West End line rises from its cut in the BMT yard above the avenue beginning at 40th Street and shadows the avenue all the way to 86th Street.

The other two photos above depict the West End Line 9th Avenue BMT stationhouse, one of many in southern Brooklyn. Most such are along the Sea Beach Line (N train) that runs primarily in an open cut. All are constructed from light yellowish brick with terra cotta trim; note that the colors here seem to be iridescent blue and green. Neglect by both the MTA and subway riders has left most of these stations in decrepit condition.

Livin’ in the USA. A pair of billboards at 9th Avenue and New Utrecht Avenue.

In the Super 70s, here at 9th Avenue and 37th Street, my father and I were amused to find here on the cemetery fence a diamond-shaped Dead End sign, right in front of the cemetery. Har-de-har har! It has been replaced since by the diamond sign with the reflector lights seen here. This is far from a dead end, since turning left will bring you to Sunset Park, while turning right will get you to Borough Park and roads leaning to Linden Boulevard, Ocean Parkway and other main routes.

A distinctive um… aroma met my nostrils as far back as 7th Avenue and here I discovered its source, two trailers packed with refuse; from the looks of things they had been here for awhile. I’ll remind you that this was one of the hottest days in July. The trailers were parked right on top of the bike lane, which, in other parts of town, is marked with thick green stripes and stenciled artwork. Here, a worn white line suffices.

Facing the scows are a pair of massive mausolea, the one at right belonging to Hubert T. Parson. “Googling” him produces this result:

The untimely and unexpected death of Frank Woolworth left a vacuum at the top of the mighty F. W. Woolworth Co. His brother, Charles Sumner Woolworth, would not accept the presidency, but each of the surviving pioneers – Fred M. Kirby, Earle P. Charlton was a Vice-President. Only seven years after the merger, any one of them would have been contentious choice with one part of the organisation or another. In the end a compromise candidate was agreed – Hubert T. Parson.

Hubert Parson was employed as an accountant by Frank Woolworth in 1892. He was a canny financial manager and one of very few people that Woolworth took any notice of. He famously once challenged Woolworth saying “You control every expense in the stores, challenging those store managers who do not put enough stamps on their letters to Executive Office. Yet you carry unbanked cheques around in your pockets for weeks at a time. Isn’t it true”, he asked Frank, “that if I dropped a nickel out of your office window here on the top floor of the world’s tallest skyscraper, you would run down to the street to pick up?” “Yes, of course” replied the Chief. “Well that is how much interest you lose every minute those cheques are not in the bank!”

Little wonder Woolworth made him the first Treasurer (“FD” in today’s language) of the merged company he had helped to set up. And in 1916 Parson was promoted to General Manager and Vice-President. Under his financial management each of the founders had become fabulously wealthy, and Parson himself had amassed a small fortune. Not even Parson himself had considered the possibility that he might succeed Frank Woolworth – but when the Board finally put the subject to the vote, he was elected unanimously. Napoleon’s desk, the palatial office atop the Woolworth Building, and the destiny of the world’s largest chain store were suddenly thrust upon him. Hubert Parson himself takes up the story, from his first General Letter to All Stores as their new President… [Woolworth Virtual Museum]

We’re halfway around Green-Wood! Continue on Part 2…