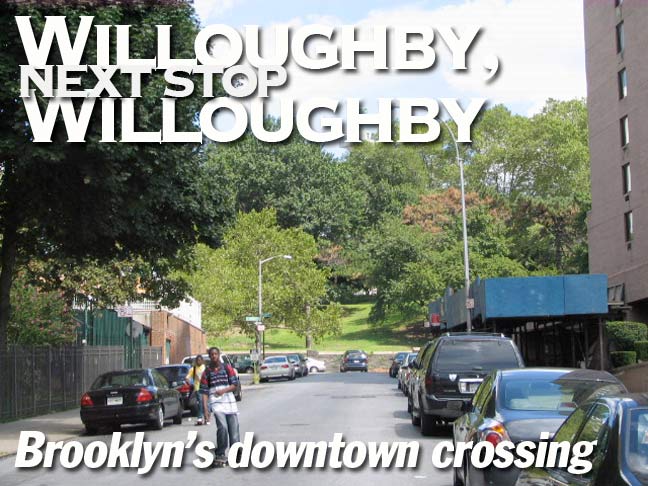

Heaven, as XTC has told us, is paved with broken glass. That means that as a resident of New York City, I’ll feel right at home if I ever get there. Today we’ll take a walk on downtown Brooklyn’s Willoughby Street, which shares the title of main business street along with Fulton Street, the big kahuna, and Livingston. All three of them have, so far, resisted the relentless call of upscale development that has swamped nearby Cobble Hill and DUMBO, and these streets blissfully still support the cheap sneakers, hair braiding and fast food joints they always have. Walking down Willoughby will also reveal some architectural secrets and marvels, as well as hints of a vanished neighborhood.

Willoughby Street runs east from the junction of Fulton and Adams Streets east to Fort Greene Park. The expansion of Adams Street into a multi-lane behemoth in the 1950s as part of the construction of Cadman Plaza cost Willoughby Street a few house numbers at its western end.

At left we see one of the unique alarm call boxes that was installed as part of Fulton Mall in the late 1970s. Totally unique ‘street furniture’ such as light poles, street signs and stoplights were installed, along with a narrowing of the road and restrictions on auto traffic (some of this can be seen on FNY’s “Dis-en-Gaged” page, so-called for the old Gage and Tollner restaurant on Fulton Street, which had recently closed when the page was written).

The bike rack looked like one of the stylized ones that Talking Head David Byrne was installing in Manhattan and Brooklyn in the summer of 2008, though I’m not sure this is actually one of them.

The first address on Willoughby is #15, labelled “Brooklyn Edison Company” on 1920s Belcher Hyde maps, but now apparently home to courts and offices. It’s a stately building if a bit drab. RIGHT: Willoughby between Adams and Pearl Streets has been closed for a public plaza, but it’s one of the more desultory ones I’ve seen.

I have not shined my own shoes in years. Neither have I had them shined by anyone else. As a rule I wear black sneakers that, from a distance, can be mistaken for real shoes. For funerals, interviews, and weddings, I have real shoes, but they are worn so infrequently that I dust them before wearing, and that’s all I have to do. I shared that because, well, take a look at the representative shoe on this shoeshine guy’s awning. I haven’t seen a shoe like that worn by anyone under 70 for quite awhile now.

Western Willoughby is thick with junk food shops. Your Wendy’s, your White Castle, your Blimpie. Word comes this week (in September 2008) that one of my favorite haunts, Burritoville, has gone kaput, and that’s too bad. The Burritoville on West 23rd and 8th Avenue was more or less the Forgotten NY office when I was away from Little Neck. I discovered it when I worked for the World’s Biggest Store, and while that chapter in the Forgottencareer is best, well, forgotten, that’s one of the few good things that came out of it. And now, pffft. Blimpie is also getting tougher and tougher to find — the two locales in midtown I frequented are gone. Blimpie beats Subway by 1000%, since at Subway there’s strict portion control. At Blimpie, they pile on almost to Jewish deli levels. I’m convinced the downfall of Burritoville can be traced to Mayor Bloomberg’s quest to have us all swallowing tofu and broccoli. Now, since your webmaster is coming off a particularly nasty stomach flu, who knows, the Billionaire may have a point. All I can tell you is, I tried sushi once and spat it out immediately. It tasted and smelled like raw fish.

That Wendy’s has been there an insanely long time. I got one of their triple decker burgers there back in 1978. A la recherche du junk perdu. Next door, though, that Automat, or the remains of it, has been there an insanely longer time.

They were ripping up the street at Willoughby and Jay for some reason; sewer replacement, most likely. On Jay between Willoughby and Fulton, there’s a string of buildings from different periods. Scattered around downtown Brooklyn are the occasional Tudor-type fronts. The building on the corner has been homogenized fairly recently but must have been quite grand in its day. (For evidence of that, take a look at the frieze over the dor in front of the “jewelry” awning — that’s evidence of the original construction.)

Upper left: former MTA headquarters, from 1950 till just recently; NYC transit now operates from 374 Madison Avenue in Midtown and from a large, ugly (IMO) building at Smith and Schermerhorn Streets. The building was constructed directly above the busy Jay Street station, which serves both the 6th and 8th Avenue IND lines and is the only station where you can walk across the platform between the A/C and F trains. The Jay Street station has a roll gate on the southbound track where the MTA’s ‘money trains’ delivered cash and tokens to MTA HQ. The money trains were discontinued in 2006, with the MTA now using armored cars.

Above right, left. On the NE corner building, a gynecologist, decked out in a tuxedo, is offering to check your breasts.

In the background is the venerable City of Brooklyn Fire Headquarters, designed in 1892 by architect Frank Freeman, an example of the Chicago School of Romanesque Revival style. its chief practitioner was Louis Sullivan, who mentored my favorite architect, Frank Lloyd Wright.

It’s a NYC tradition that temporary lightposts are constructed with flimsy, pyramidical wooden bases, many held down by sandbags, topped by a thin pipe ending in whatever luminaire is in vogue at the time. When I was a kid, you saw there with curving “crescent moon” lumes lit by incandescent bulbs. Good to see the tradition continues.

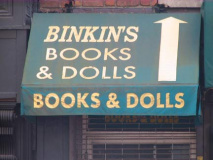

The very Irishness of Kevin Barry’s Bar & Grill is sort of incongruous on Willoughby Street, where I assume I’m the only even partial Irishman for miles. Perhaps they bus them in (paddy wagons?). Leaving that aside, I’ll direct your attention instead to next door, where we have Binkin’s Books & Dolls. This conjures all sort of images into my perhaps too-feverish mind. You know what… it’s a fact that too few Americans read in this short-attention-span society, and just about every possible method has been attempted to get people in the reading habit. But there’s one way that hasn’t been tried. Yes, I am talking about sex. Imagine a library where the librarians are dressed like Hooters girls. Or in bikinis. Or whatever turns you on. The libraries and bookshops would be packed. And that, I hope, is the idea that Mr. Binkin is perusing.

Outdated sign at Jay Street subway station for ?Helen Keller Services for the Blind, named for the famed ?author and lecturer (1880-1968) who lost her sight and hearing before age two. The institution changed its name in 1985, and Lawrence Street, above the station, is named Helen Keller Place.

Telephone Building

The most beautiful building on Willoughby Street is also one of Brooklyn’s most gorgeous.

This Beaux Arts edifice, on the north side of Willoughby between Lawrence and Bridge, used to be the New York and New Jersey Telephone Company Building, built in 1898. What architect Rudolph. I. Daus cleverly did is to carve telephones all over the building, the old-fashioned 1898 type, when you had to have the operator put the call through for you.

The building’s rounded corner makes it appear to be sailing up Willoughby Street like a magnificent ocean-going vessel. The building contains many cartouches (scroll-like ornaments) and arched windows just below the roof, and a porthole window is accentuated by a portrait of Mercury, the Roman messenger god. Architectural exuberance at its best, and architectural exuberance is never irrational.

The Other Telephone Building

One good telephone headquarters deserves another, and in 1931 NY Telephone followed up the Beaux Arts stylings of the Daus building with the Art Deco vertical lines of Ralph Walker, considered the father of the Art Deco skyscraper.

Walker made the bricks ‘ripple’ on the exterior both by creating subtle differences in the colors and also “rippling” the bricks, with slightly uneven surface that is especially noticeable when the sun shines on it from an angle.

The building has recently been converted to luxury residences known as BellTel Lofts. Buyers and prospective buyers have their own blog.

LEFT: Donuts and check cashing, Willoughby and Bridge Streets. RIGHT: 4 Metrotech Center, Willoughby and Duffield Streets, JP Morgan Chase, was constructed to harmonize with the older BellTel building.

A peek north on Duffield Street, named for one of the first doctors in Brooklyn Village in the colonial era (family heiress Margareta Duffield married dry goods enterpreneur Samuel Willoughby, who later founded Brooklyn Bank) reveals the twin spires of the The Catholic Church of St. Boniface Under the Supervision of St. Philip Neri. The church was built in 1872 and designed by renowned 19th Century ecclesiastical architect Patrick Keely.

The Temporary Nothing

“So when I come in the Mall, and then I start to roam, you wouldn’t think it’s a store, you would think it’s my home.” –Biz Markie

In late 2008, there was a big empty space in the odd-shaped lot defined by Willoughby Street, DeKalb Avenue, Albee Square and Fleet Street. This is the former locale of the Albee Square Mall (photo below right), which held forth here between 1979 and 2007. The site’s new owners plan to build a giant residential complex, City Point, consisting of close to 1000 units, plus a million square feet of retail space (including another Target, a few blocks away from the one at Atlantic Avenue) and 125,000 sq. feet of office space. Since the economy was in near-ruin in late 2008, we’ll have to see if there’s any delay in these grand plans.

Until anything is built here, the empty lot vouchsafes fine views of several Brooklyn landmarks, including the Dime Savings Bank dome. From FNY’s Albee Square page:

The Dime is an Ionic-columned neo-Classical palace built between 1906 and 1908 by architects Mowbray and Uffinger. The interior is one of Brooklyn’s most magnificent indoor spaces: the central dome is defined indoors by a ring of twelve marble Corinthian columns crowned, at the top, by gilded representations of the obverse and reverse of the “Mercury” Dime. Since “Mercury” dimes were issued between 1916 and 1945 these must have been added sometime after the bank was opened in 1908.

We can also see the giant Williamsburg Bank tower, Brooklyn’s tallest, just recently unshrouded from construction that converted it from the House of Pain (it was filled with the offices of oral surgeons; your webmaster has been treated there) to the House of Gain, as it now boasts deluxe condominiums.

Probably the landmark shown here that had the most impact on my life, though, was the Dime Savings Bank neon sign and clock/thermometer, which can be seen for much of Flatbush Avenue. Whenever I would get off the B45 bus taking me to high school, I would see it shining forth, as did all the surrounding motorists. Perhaps it will be turned on again someday.

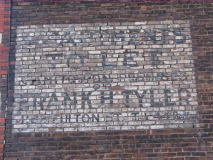

A look at a parking lot at Willoughby and Albee Square, empty on this Saturday, reveals a very old painted ad for Frank H. Tyler, realtor, and a very old phone number: 44 Bedford.

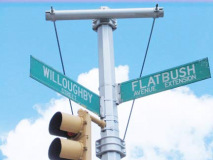

There hasn’t always been a Flatbush Avenue here. It’s a relatively late addition: Flatbush Avenue Extension, along with the Manhattan Bridge it serves as the approach ramp, are both celebrating their centennial.

The Extension through much of its history has been lined with factries and auto body/collision shops; this is the province of pedal to the metal traffic. In recent years, though, a number of tall condo towers have sprung up as the area changes character.

The NYC Department of Health has been here since the 1920s, but this building looks like 1950s streamline.

Here’s a 1929 Belcher Hyde map of the area including property lines. No other Brooklyn neighborhood’s map has changed as much as Downtown Brooklyn’s over the last 80 years. Discussing streets alone, Lafayette Street, Bolivar Street, Debevoise Place and Hudson Avenue have disappeared (swallowed by University Towers and the Long Island University campus). For a comprehensive look at what Downtown Brooklyn streets are no longer there, see FNY’s Street Necrology.

Brownstoner: Built as rental housing in the late ’50s for Long Island University faculty and staff, University Towers, three sixteen story apartment buildings on 5.5 acres, was converted to a moderate-income cooperative in 1989. The units look enticing, at least on their website.

While part of the Long Island University campus consists of the inimitable Brooklyn Paramount Theatre on DeKalb Avenue and Flatbush Avenue Extension, LIU also constructed some ugly, monolithic buildings in the 1980s that shout: “Bureaucracy.”

Above right: slanting Fleet Street is a remnant of the area’s old street plan. LEFT: this walkway between Willoughby and the FAE was once open to traffic as University Place; before that, it was called Debevoise Place.

The Last Mohican

The stretch of Willoughby past the University Towers between Fleet Street and Ashland Place contains Brooklyn’s last remaining “humpbacked” street sign, designed to show both the street you’re on and the cross street. We can also use this sign to determine a lost cross street as well.

Willoughby Street was formerly crossed by Hudson Avenue here. The north-south avenue now exists only in two short pieces for a few blocks in Vinegar Hill and a one-block stretch Downtown beteen DeKalb Avenue and Fulton Street. It was carved up by the construction of Farragut Houses, Ingersoll Houses, University Towers and LIU.

A driveway on the University Towers campus was built over its former route. What would become the Fifth Avenue El also traveled over Hudson Avenue between the Myrtle Avenue El and Flatbush Avenue from 1888 until 1940.

DOT, spare this sign! I’ve noticed that after I feature a nonstandard sign on FNY, it invariably is removed. It would be a shame if this last in-situ humpbacked sign were removed.

Update: Google Street View confirms this sign had been removed by September 2014

Raymond Street Jail

Wide Ashland Place runs from the Williamsburgh Bank Building at Flatbush Avenue and Hanson Place north to Myrtle Avenue and Navy Street. Its former name was Raymond Street; perhaps the name was changed so that memories of the now-vanished Raymond Street Jail, which stood at the Se corner of Ashland Place and Willoughby from 1838-1963, could be expunged.

The Brooklyn City Prison, as it was then known, was not taken over officially by the Department of Correction until January 1, 1908 and in the Official Report for the Department of Correction for 1908, we find the following description of the institution at the time:

Males were confined in dark, smelling cells with no light whatever, except that furnished from a flicker of a candle, a luxury to be enjoyed by those who had the means to procure this and at an exhorbitant price. The odor arising from the cells was almost unbearable.

In the female’s prison, some eighty years ago, the conditions were largely the same. — History of Detention in Brooklyn

Fort Greene Park

The east end of Willoughby Street is in sight, at Fort Greene Park. The 30-acre quadrilateral is located between DeKalb and Myrtle Avenues on the north and south, St. Edward Street and Brooklyn Hospital on the west, and Washington Park (as Cumberland Street is called here) on the east.

It is named for a fort built in 1776 at what is now the parkís central summit by General Nathaniel Greene (1742-1786). The fort, originally named Ft. Putnam, aided in George Washington’s retreat after his defeat in the Battle of Brooklyn in 1776, and was reactivated during 1812 when a British attack was anticipated.

Walt Whitman, editing the Brooklyn Daily Eagle from 1846 to 1848, pressed for a public park in the area, and in 1847, Washington Park, named for the President, began development. Whitman lived nearby, at 99 Ryerson Street in a building that still standing, and it’s not surprising he wanted a park near his home.

Washington Park was designed by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux, the architects who went on to develop Central and Prospect Parks. It was officially opened in 1850; in 1897 the park was renamed for Fort Greene, which by then had become a handsome residential neighborhood. The two-block stretch of Cumberland Street lining Fort Greene Park’s eastern side is still called Washington Park.

During the Revolutionary War, the British anchored eleven prison ships in Wallabout Bay (the body of water west of Williamsburg) and subjected American prisoners of war to deprivations and torture during the years 1776-1783. More than 11,000 died in the ships.

There were early monuments to those who became known as the “prison ship martyrs”: some of the remains were buried in the vicinity of the Navy Yard in 1808 and interred in Washington Park in 1873.

The current monument, a 148-ft. Doric column (one of the world’s largest), was designed by McKim, Mead and White (the firm that would later design Pennsylvania Station) and dedicated by William Howard Taft, then President Teddy Roosevelt’s Secretary of War, in 1908. The monument originally featured a staircase and elevator to its summit, where there was a lighted brasier and observation deck. The elevator was broken by the 1930s and was finally removed in the 1970s. The Prison Ship Martyrs Monument, however, remains one of Brooklyn’s more striking landmarks, visible from any part of the neighborhood especially in winter. The remains of the prison ship martyrs are interred under the monument.

As of the summer of 2008 the monument remained inaccessible to the public because of ongoing renovations (which, by the sign posted on the fence, were supposed to be completed in mid-2007). When/if the renos are completed, the brazier will be relit; four bronze eagles that originally were positioned on 4 points around the monument plaza will be restored; the stairs and crypt will be cleaned and renovated; and the monument will be strategically lit at night.

The Doric-columned Fort Greene Park Visitors’ Center echoes the monument’s single column; it, too, was designed by McKim, Mead and White.

Willoughby resumes on the east side of Fort Greene Park, but this is Willoughby Avenue, and Clinton Hill, the neighborhood we’re in now, is way too big to tack onto the end of this FNY page!

2 comments

[…] If you are on a budget consider the free weekend shuttle which usually departs from Jay St at Willoughby St after every 20 […]

[…] This one actually broke my heart a little bit, because when I was doing my initial research, I found a picture of it on the Forgotten NY website. […]

Comments are closed.