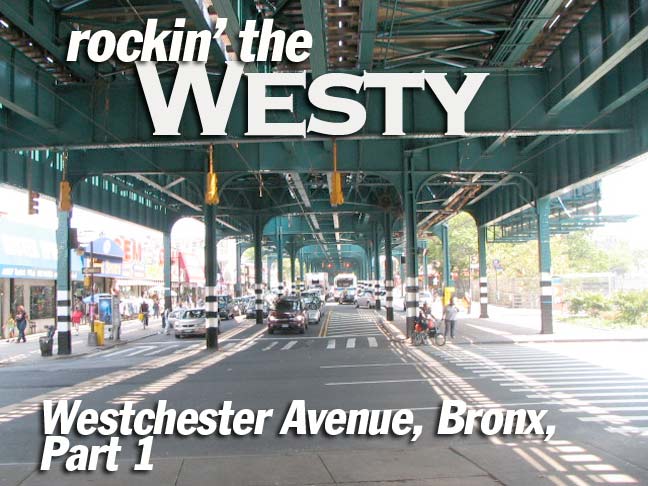

I love els. From Brooklyn’s New Utrecht Ave., Livonia Avenue, Broadway of Brooklyn (Manhattan’s Broadway is elled too) to Queens’ Liberty and Jamaica Avenues, Roosevelt Avenue and Queens Boulevard (that el is all shot and ready to go on a future piece) despite the noise and crowds, els hold a fascination for me…Forgotten artifacts seem to be more often found beneath them; ancient streetlighting, for example. I hadn’t greatly explored the Bronx’ great el expanses, Jerome Avenue, White Plains Road, and Westchester Avenue, until now; a two-part walk down Westchester Avenue, which goes for about 4 miles from The Hub to Pelham Bay Park, is the beginning of such explorations.

Westchester Avenue is a very old road; according to the late great Bronx historian John McNamara in History in Asphalt, it was first traced in the colonial era as a path from the Morris family estate to the town of Westchester, whose seat is now called Westchester Square (see below). Until 1874 all of the Bronx was floated in Westchester County; it became part of NYC in sections, with most of the Bronx west of the Bronx River annexed that year, east of the Bronx River in 1895 (City Island the following year). The whole territory became the Borough of the Bronx when Greater New York was created in 1898, and finally, the Bronx became a county on its own in 1914.

Westchester Avenue was graded from Coles’ Boston Road (now Third Avenue) to the town of Westchester in 1867, when it was known as the Southern Westchester Turnpike (to differentiate it from Westchester Turnpike proper, now followed in great part by US Route 1). Sometime before the turn of the century, as the area gradually urbanized, the name was changed to Westchester Avenue.

East Westchester

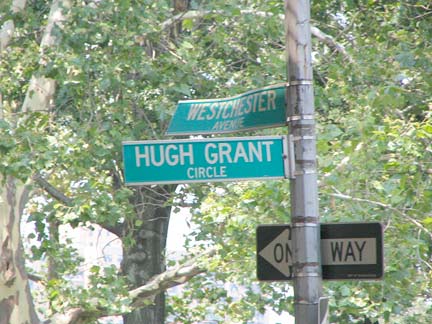

I’m covering Westchester Avenue sort of in reverse, walking its eastern section from Hugh Grant Circle (where it meets White Plains Road and the Cross Bronx expressway) east and northeast to Pelham Bay Park. I will cover Westchester Avenue from The Hub to Hugh Grant Circle sometime soon.

Hugh Grant Circle was not named for the cheeky British actor of Four Weddings and a Funeral and Bridget Jones’ Diary fame, but rather a NYC mayor between 1889-1892; he was the youngest mayor in NYC history, taking office at age 31, and the first Roman Catholic NYC mayor. Just why the circle was named for him in 1904, though, is not clearly understood, because citing his opposition to NY State’s intervention in city matters, he opposed the creation of The Bronx’ two biggest parks, Van Cortlandt and Pelham Bay.

Hugh Grant Circle was not named for the cheeky British actor of Four Weddings and a Funeral and Bridget Jones’ Diary fame, but rather a NYC mayor between 1889-1892; he was the youngest mayor in NYC history, taking office at age 31, and the first Roman Catholic NYC mayor. Just why the circle was named for him in 1904, though, is not clearly understood, because citing his opposition to NY State’s intervention in city matters, he opposed the creation of The Bronx’ two biggest parks, Van Cortlandt and Pelham Bay.

Hugh Grant Circle skirts the southwestern edge of Parkchester, a housing project constructed in 1942 by the Metropolitan Life Insurance Company. Met Life provided Parkchester with a rather whimsical style. While the tall seven and twelve-story buildings appear somewhat monolithic when viewed from afar, a walk around the complex reveals the friendly face Parkchester presents: its generous employment of colorful, playful terra-cotta statues and sculpture.

ABOVE: Parkchester’s main street, Metropolitan Avenue

At Grant Circle and the Cross Bronx Expressway is the monolithically Deco Emigrant Savings Bank, originally Dollar Savings Bank. Dollar originated in 1892, acquired Dry Dock savings Bank in 1983 to form Dollar Dry Dock, and was acquired by Emigrant Savings in 1995.

Note the symbol above the door: it depicts the Morgan Silver Dollar, minted between 1878 and 1904 and again briefly in 1921. It was known as the Morgan dollar for its designer George T. Morgan. The dollars were minted at Philadelphia, New Orleans, Carson City, NV, Denver and San Francisco.

Though the Parks Department promotes Hugh Grant Circle as a park on its online listing, this is really the only green part of the circle; most of it is taken up by the cavernous concrete elevated Parkchester station of the IRT #6 (Lexington Avenue line). Underneath the el, there’s a newsstand (that hides its handsome handlettered sign off to the side) and parking for MTA vehicles. This ought to be the transit gateway to the eastern Bronx; in my opinion, the MTA is missing the boat by not spiffing it up and constructing an inviting plaza here. I suppose the el and what drips off of it are the main impediments to that notion, though.

Westchester Avenue, looking east from the Cross Bronx Expressway Parkchester is one of 3 concrete-clad el stations on the #6 el between Whitlock Avenue and Pelham Bay Park. This was the end of the line for a few months in 1920; as el construction pushed east, the final station, Pelham Bay Park, opened December 10 of that year. When the Cross Bronx Expressway was built in the mid-1950s, the pillars were extended deeper on concrete stanchions. The station was originally known as East 177th Street, a wide boulevard replaced by the Cross Bronx.

Westchester Avenue is the only street in NYC that is home to two separate elevated lines. The IRT White Plains road el serving #2 and #5 lines runs along the avenue between Third Avenue and Southern Boulevard, and the IRT Pelham Line serving the #6 line joins it at Whitlock Avenue and runs all the way out to Pelham Bay Park. Two short stretches of Westchester Avenue see daylight: between Third and Brook Avenue and again between Southern Boulevard and Whitlock Avenue, a grand total of about 7 blocks.

Circle Theater, a couple of doors down from the old Dollar Savings Bank, is now a Lucille Roberts salon of sweat. When Donald Gilligan first shot the Circle in 1999 for a FNY page, some of its old facade was still intact. The theatre stopped showing films in 1985.

Grant Square is where Westchester Avenue and White Plains Road intersect the Cross Bronx Expressway, and here you will find what’s possibly the last of the hundreds of original light posts installed when the roadway was constructed between 1948-1962 — one of the very few curved-mast, cylindrical shaft NYC lampposts remaining. Like other NYC lampposts, it is date-stamped; this one from 1954.

The Cross Bronx Expressway was one of transit czar Robert Moses’ most difficult and controversial projects.

NYCRoads: The 8.3-mile-long, six-lane Cross Bronx Expressway, which runs through the heart of the South Bronx, was perhaps the most challenging of the expressway projects. Constructing the expressway required blasting through ridges, crossing valleys and redirecting rivers, while causing minimal disruption to the apartment buildings that topped the ridges in the area of Grand Concourse. Furthermore, the expressway had to cross 113 streets, seven expressways and parkways (either completed or under construction), one subway line, five elevated lines, three commuter rail lines, and hundreds of utility, water and sewer lines. None of these lifelines could be disrupted during construction of the Cross Bronx Expressway. According to expressway designer Ernest Clark, constructing the seven-mile road was “always measured in inches and tenths of inches.” Rock was blasted and chiseled out from supporting girders so carefully that construction crews “took the stuff out with a teaspoon.”

And: The route of “Section 3” would displace numerous residents in the East Tremont and Morris Heights neighborhoods. Specifically, 159 apartment buildings would have to be demolished, displacing 1,530 families. An alternative route was available in the area of Crotona Park that would have reduced the number of families that would have to be displaced. Moses rejected the alternative plan, despite its support from the East Tremont Neighborhood Association.

Though residential opposition failed to dissuade Moses from his original route fro the Cross Bronx, it was successful in getting him to reroute the Brooklyn Queens Expressway in the mid-1950s from a path that would have bisected Brooklyn Heights to a more workable waterfront route, and in the mid-1960s, the Lower Manhattan Expressway that would have run across Tribeca was finally cancelled in 1972.

Just past the Cross Bronx, Westchester Avenue moves into the neighborhood of Unionport. McNamara is silent on the origin of this name, though it may have to do with its location on the west bank of Westchester Creek. Unionport Road still runs as a main route from adjoining Castle Hill through Parkchester to Bronx Park. Castle Hill was named for a slight elevation noticed by 17th-Century Dutch explorer Adrian Block, who thought it resembled a castle.

These very old buildings likely predate the el’s construction in 1920; 2030 Westchester (above) likely once had an expansive lawn.

The Church of St. Helena on Olmstead Avenue likely took over this nearly windowless wood structure: could it have been a granary or storeroom of some kind?

I liked the lightning bolts above the letters on the Castle Hill Electrical Supply Corp. (A few of them have fallen off over the decades).

A. Hupfels Sons Beer, Jos. Wagner’s Scheutzen, Westchester and Castle Hill Avenue. “Scheutzen” can be translated as “shooters” — could this once have been a shooting range?

ForgottenFan Danny Siegel: The sign on the side of the building @ Westchester and Castle Hill Avenue actually reads Jos. Wagner’s Schuetzen Park. My business, Varsity Army & Navy has been in this building since 1938 on the Castle Hill side. We still have the original sign from our remodel in 1953. My understanding is that it used to be a beer garden at least until Prohibition. There is still evidence of the concrete patio that used to have tables and chairs in the back. It was the bar that was in the movie, The Pope of Greenwich Village. It closed about a year after the movie was filmed there.

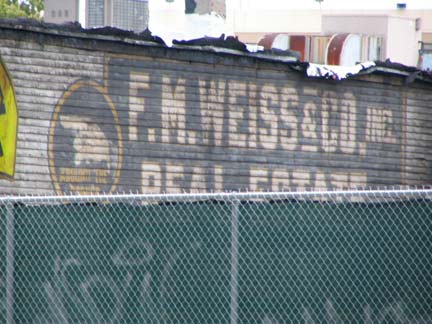

Rumor has it that there used to be a bowling alley in the basement, but I can’t find any remnant of it down there. The Westchester Square Plumbing Supply was a pet store in the 1930-1940 range that sold pigeons according to my father. The old sign that you saw in Westchester Square behind the fence that reads FM Weiss [see below] only became visible this past winter after a terrible fire that resulted in the entire building being demolished. There are some great old houses on all the side streets along Westchester Ave from Castle Hill to Westchester Square including two old wooden schoolhouses from the 1800’s (see building marked St. Helena’s above).

[Hupfel’s Brewery] was located on St. Ann’s Avenue from E. 158th to E. 160th, the vaults extending back into the hillside of Eagle Avenue. A few old-timers swore the caverns tunneled under St. Ann’s Avenue as well. The original brewery was owned by an Xavier Grant, who sold it to a Mr. Schilling. In 1863, Anton Huepfel [spelled this way] bought the brewery and it passed to his 2 stepsons who had taken his name. They were Adolph and John. The partnership dissolved in 1883, and Adolph became the sole owner. He had 2 sons and 2 daughters, the elder son studying brewery and bacteriology in Berlin and Copenhagen. This was Adolph G. Hupfel (he americanized the name) who later adapted the brewery to a mushroom plantation during Prohibition. The family plot of this brewing family is adjoining those of the Eichler and Kolb families (two other noted Brewery owners) in Woodlawn Cemetery. John McNamara, via House Of The Ferret Antiques

“New Gumball” lamp with newly installed fire alarm light at Castle Hill Avenue.

Crossroads Tabernacle, Castle Hill Avenue between Westchester and Lyon Avenues, was once the RKO Castle Hill Theatre, as architectural elements illustrate. According to Cinematreasures comments, it was constructed in 1927 by architect William Shary. Here it is as it appeared in 1940 when “Buck Benny Rides Again” was the feature presentation, and a 1953 view after it joined RKO.

(Forgive me if those links don’t work in the future — for some reason, they seem to change or are taken down rather frequently.)

According to the comments, Jerry Lewis, the Three Stooges and DJ Clay Cole of the American Bandstand-ish Clay Cole Show (1962-68) all appeared at the Castle Hill. Here’s Cole in Twist Around The Clock.

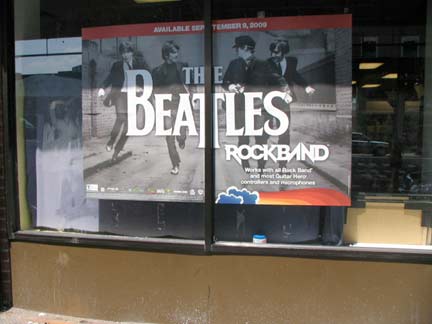

The Fab Four somehow missed the Castle Hill Theatre during their NYC visits, but they’re making their umpteenth comeback with a video game in the fall of 2009.

NYC vent

Westchester Square Plumbing Supply, Westchester and Glebe Avenues. There’s a big half dome at the roof, indicating some ostentatiousness — the building was a big deal at one time, perhaps a bank. It has been saddled with a clashing remake at the street level. “Glebe” sounds like a water bird, but the term actually refers to an area of land belonging to a beniface, or land grant given as a reward for services rendered, in Roman Catholic and Anglican tradition. Originally, St. Peter’s Episcopal Church granted 20 acres to Rev. John Bartow to remain as pastor in 1702. Glebe Avenue follows the course of the now-buried Indian Brook.

St. Peter’s Church

From the ForgottenBook: St. Peter’s Episcopal Church was built in 1856 by Leopold Eidlitz when this was an isolated country village along the South Westchester Turnpike, and then rebuilt by the architect’s son, Cyrus, after a fire in 1877. St. Peter’s has existed as a parish since 1693 and is the third church to exist on this site. The old St. Peter’s Parish House, now no longer standing, actually served very briefly as New York State Capitol in the 1790s when a plague forced lawmakers away from lower Manhattan (Albany was named state capitol in 1797). St. Peter’s churchyard contains many graves dating back to the early 1700s. Foster Hall, facing Westchester Avenue in the cemetery, was built by Leopold Eidlitz in 1868 and is currently used as a community theater.

Removed bluestone sidewalk slabs outside St. Peter’s churchyard.

Foster Hall is the home of the 82-seat Center Stage Community Playhouse. It is one of the oldest in the brough; since 1969 it has presented productions such as Cabaret, Damn Yankees and Hair. Though it only does three plays a year, it has been forced to stage a fund drive in 2009; response has been positive.

Directly across Westchester Avenue from St. Peter’s, the Civil War-era Thomas Bible Funeral Home was replaced recently by a flock of Fedders-style multifamily buildings.

St. Peter’s Churchyard

St. Peter’s graveyard contains some stones dating back to the era of the original St. Peter’s constructed in 1693. I didn’t find any quite that old but there are several from the 1700s remaining here.

Gravestones before 1800 were usually slender, square sandstone or slate slabs. Between 1830 and 1860, more elaborate sculptured stones of white marble were used. These stones were and are subject to growths of obscuring and damaging lichen and moss. From 1860 to 1880, gravestones tended to be square, massive marble stones of elaborate shapes or with decorative, ornate sculptures. The period between 1880 and 1910 brought the use of soft grey granite for gravestones. Unfortunately this type of stone was extremely subject to weathering. Spirited Ghost Hunting

Ironically the oldest stones here at St. Peter’s — and any older cemetery — are much easier to read because the sandstone has held up so well across the centuries. The marble and granite stones have weathered too greatly in some cases to be read.

ForgottenFan Eric Weaver: Most degradation of tombstones is due to acid rain. Most acid rain in New York comes from coal fired electric power plants in the Ohio River valley. Limestone and marble are most susceptible to acid. Granite also weathers from the acid. An example is the granite Cleopatra’s Needle in Central Park that has suffered greatly in the 150 years in New York compared to the 3500 years in Egypt. Sandstone holds up much better to acid rain.

Owen Dolan and The Chair

Westchester Square was originally the town center of Westchester and was in Westchester County. Here Westchester Avenue meets the Bronx’ longest street, East Tremont Avenue. Strangely enough when the area was settled by the Dutch in the early 1600s it was called Oostdorp, or East Village — east of New Amsterdam. When the British took command it was situated west of the New England colonies and so became Westchester. It was the site of a Revolutionary War battle in which patriots held off attacking British, allowing General Washington to maneuver a strategic retreat.

The “Seat” in Westchester Square is one no one is allowed to sit in. David Saunders‘ sculpture was installed here in 1987 opposite the Huntington Free Library; under the chair is a sculpted dictionary open to an entry on the birds of North America. “Seat” was created in Saunders’ studio in Greenwich Village and cast at the Art Foundry in Santa Fe, NM.

Nearby, the Owen Dolan Recreation Center recalls an area educator who spoke at a dedication of a World War I memorial. After Dolan finished the speech, he promptly had a heart attack and dropped dead.

The Westchester Square area preserves some aged buildings as well as some old painted ads. Note the Flemish-style stepped building on the corner photo left and the F.M. Weiss real estate sign (see above).

Cooper Street, an unmarked dead end just north of Tremont. A ramp leads from the Pelham el to the massive Westchester Yards, where trains plying the #6 are serviced. Beyond the yards in the distance is the Bronx’ Hospital Row along Williamsbridge Road, where you will find Montefiore and Calvary Hospitals.

Just before Westchester Avenue crosses Westchester Creek and the Hutchinson River Parkway, it forms another triangle with East Tremont Avenue. Here you will find a large painted sign advertising a tattoo parlor, a rusted lamppost classic from 1954 and a Little League field. The interestingly named Tan Place was renamed Little League Place in 1984. The old name is thought to recall a teamster named Timothy A. Naughton, or was so named because it meets the two long avenues at a tangent.

Middletown

After crossing the creek Westchester Avenue enters Middletown, so named perhaps because it was midway from the village of Westchester to the Pelham Bridge. The adjoining Stinardtown, just to Middletown’s northeast, was wiped out when Pelham Bay Park was created in the mid-1800s.

A couple of typical-for-this-part-of-town houses, and an almost preternaturally smooth-exteriored office building at Mulford Avenue.

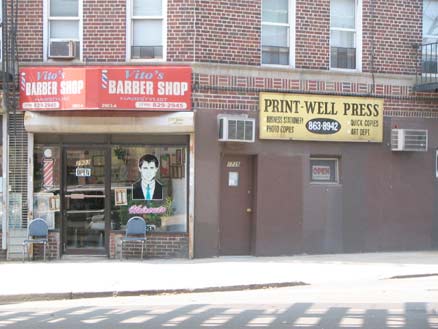

An awning sign and ad at Pilgrim Avenue. The Print-Well Press sign is at least a few decades old but still does the job after all these years with black on yellow type. It can’t be older than the 1960s because that is when they started phasing out the lettered telephone exchanges; this one is all numbers.

Underside, Buhre Avenue platform. The fare control areas of a number of el stations preserve the wood planking on the floors.

Middletown has two clusters of “theme” streets: “colonial,” as in Pilgrim, Plymouth, Mayflower, Puritan, and Bradford, and “electrical research”: Edison, Watt, Ampere, Ohm, Research, Radio Drive. The latter were inspired by land donated to the city by Isaac Leopold Rice (1850-1915), chess champion and president of the Electric Storage Battery Company; his wife Julia was organizer of the Society for the Suppression of Unnecessary Noise, which successfully elicited the support of Mark Twain.

Middletown veterans are listed in alphabetical order on this war memorial at Westchester, Hobart and Buhre Avenues. However, which war is unclear at least on the memorial itself.

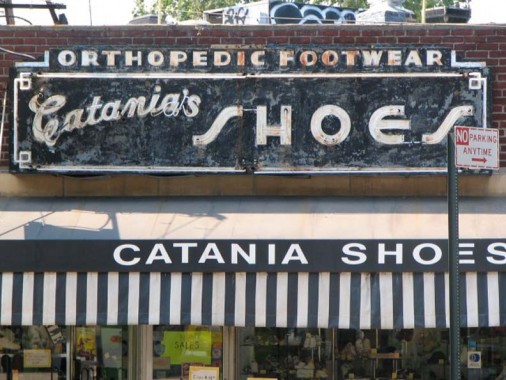

I hadn’t noticed this terrific Fab Forties-era neon sign for Catania’s Shoes on Westchester near Hobart before. Is it recently uncovered? Does the neon work at night?

Unusually, the corner of Hobart and Westchester was named for its honoree while he was still alive. Michael Crescenzo Triangle was named for the president of the Pelham Bay Taxpayers and Civic Association in 1993; he passed away at age 91 in 2008. Until the mid-1980s all Bronx street signs were blue and white like this, but they were changed to green and white due to regulations changes from the federal government.

The Bronx has a number of streets that turn up where you wouldn’t expect them. While Morris Park Avenue runs through its titular neighborhood, there used to be a second section that ran for a few blocks in the Pelham Bay-Middletown area. It’s unknown why this section, formerly known as Liberty St. and Alice Avenue, was renamed Morris Park Avenue. In any case, in 1968 Morris Park Avenue became St. Theresa Avenue in honor of the parish it runs past. St. Theresa was founded in 1927 and the existing, modern church dates to 1970.

In the Roaring Twenties, Pelham Bay was far from the heavily populated, suburban neighborhood it is today. Indeed, the Bronx itself had only recently seceded from Westchester County and become part of New York City. Farmland covered much of what we now know as Mulford, Mayflower, Pilgrim and Wilkinson Avenues. Where now prominently stands 1950 Hutchinson River Parkway was a water-logged swamp with a meadow and dirt road running through it. One house stood where Hutchinson River Parkway now meets St.Theresa Avenue. A chicken market occupied the area where Mulford Avenue meets Wilkinson Avenue and the area between Pilgrim Avenue and Mayflower Avenue hosted goat farms. St. Theresa Parish

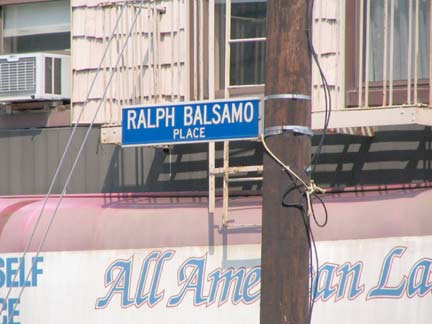

Here’s a first… a blue and white sign honoring a gangster?

One of the 29 people arrested yesterday [Feb. 23, 2006] is Ralph Balsamo, a Genovese soldier known as the Undertaker because his day job was running a Bronx funeral parlor where the crime family was said to have held many meetings, prosecutors said. According to the charges, Mr. Balsamo also ran a major cocaine distribution network in the Bronx and Westchester. One of his top managers, Mr. Garcia said, was a Genovese operative, Michael Londonio, 29, who was killed on Dec. 6 in a shootout with two state troopers at his home in Throgs Neck, the Bronx. New York Times, February 24, 2006 And later… A co-defendant, Ralph Balsamo, who was the head of the Hunts Point crime gang and a member of the Genovese crime family, had earlier pleaded guilty to enterprise corruption. Known as the “Undertaker” because his day job involved running a Bronx funeral parlor, Balsamo was sentenced to between 21/2 and 71/2 years in prison, and fined $50,000. [John] Caggiano worked as Balsamo’s lieutenant in the Hunts Point gambling enterprise, authorizing and supervising gambling activities. Caggiano’s father-in-law is Dominick “Quiet Dom” Cirillo, the former acting boss of the Genovese crime family, according to the district attorney’s office. Mafia Today, August 27, 2008

So, is that “the” Ralph Balsamo on the street sign?

Turns out that the Ralph Balsamo on the street sign is the mobster’s father. I put that question to the office of City Councilman James Vacca.

His deputy chief of staff Bret Nolan Collazzi wrote me: [The] honorary street sign refers to the elder Ralph Balsamo, former owner of the funeral home and (to Jimmyís knowledge) not a suspected criminal figure. The street naming predates Jimmyís time in the Council (and the sonís indictment) by 15 to 20 years. I know it probably looks strange now to those who are familiar with allegations against the son, but the father was a longtime figure in the community and itís common to honor merchants who have such a big impact on so many people. I wonder if there’s precedent elsewhere in the city for something like this.

Indeed.

Both the el and Westchester Avenue take a number of twists and turns approaching Pelham Bay Park including here at Wilkinson Avenue. This section of Westchester Avenue is the “newest” — it was extended from Westchester Square to Pelham Bay Park in 1917, probably as a roadway under the el, which was completed in 1920 (in Queens, Roosevelt Avenue is an extension of Greenpoint Avenue built along with the el in 1917).

These orange fire alarm lamps are being attritted out in favor of the red cylinder seen at the top of the luminaire.

Westchester Avenue comes to an end at Bruckner Boulevard, where you will find Sophie’s Diner, the Pelham Bay Park el terminal, and Bronx’ largest park, Pelham Bay Park at over 2700 acres in size. Among the feaures located therein are the 1933 Bronx Victory Column, Glover’s Rock, Split Rock, the Thomas Pell Wildlife Sanctuary and the Pell Mansion. Take an online tour at NYC Parks.

9/6/09