The name Boerum pops up a couple of times in the Brooklyn gazzeteer (a map, for those of you in … ah, I won’t finish that joke, I’ll get in trouble). As with so many other somewhat foreign-sounding names in NYC, it commemorates a Dutch colonial family: Willem Jacobse Van Boerum immigrated to New Amsterdam in 1649, and his great grandson Simon Boerum owned a large amount of land south of what is now downtown Brooklyn in the years prior to the Revolutionary War. Boerum Place and the community of Boerum Hill (the hill was leveled long ago) commemorates him, and there’s a Boerum Street in East Williamsburg. Boerum Hill is one of a few distinct neighborhoods in a tightly packed region that also includes the communities of Gowanus and Cobble Hill. I took a walk in November 2009 in Boerum Hill, which includes a couple of landmarked blocks along Pacific, Dean and Bergen Streets, as well as its main north-south arteries, Nevins, Bond and Hoyt Streets.

When you get off the IRT at the Nevins Street station (2, 3, 4, 5) you find yourself on a stretch of Flatbush Avenue that is lined with tall office buildings but is yet something of a no-man’s land between the bustling Fulton Mall and Park Slope, which is heralded by the 45-story Williamsburg Bank tower (once the House of Pain — filled with dentists and oral surgeons, but now condo-ized as One Hanson Place). This was once a haberdashers’, or men’s clothing, shoes and hats, row but they disappeared during the 1960s, leaving something of a vacuum that has yet to be filled. The tallest building with the arched entrance in the center is the former Pioneer Warehouse.

My pal, tour guide and urban explorer Moses Gates, just sent me a featured page on his All City New York showing the Willie’s observation deck and historic signage, which he had obtained on a trip in 2005 with former Satanslaundromatter Mike Epstein. Quite some time ago, the deck was open to the public, but the deck and roof now belong to a not-yet-sold condo unit, which has some kind of view.

More: Willy’s Peak [Shane Perez]

While the banded-masonry building with the large arched entrance at the SE corner of Flatbush and Nevins Street is impressive as is, albeit giving an aura of faded glory, it was once a great deal more showy — the tower, now cut back to just 7 stories, was once 17 stories/225 feet tall and boasted a clock tower! It was built in 1893by men’s clothier Smith, Gray and Co. to replace an earlier 1888 clock tower that had fallen onto the Fulton Street el.

Smith, Gray went bankrupt in 1914 and the building has been home to mixed uses ever since then; pawnshops, pool halls and cafeterias have occupied the first and second floors. The clock tower was demolished in the 1940s and the building was cut back to its present 7-story height, and the shortened tower is now nearly vacant. The NY Times’

Christopher Gray: “It is, like the Roman Colosseum in Lord Byron’s play Manfred, ‘a noble wreck in ruinous perfection.’ ” A cast-iron Smith, Gray building on Brooklyn’s Broadway in Williamsburg has been landmarked but not this one.

We’ll turn to Christopher Gray again for an explanation of the transcendent 16 Nevins, an Alpine chalet-type building constructed inn 1922: The restaurateur Joseph J. Sartori had the architect Arthur Starin create a startling surprise of rough stucco, heavy roof tile, mock half-timbering and ingenious decorative elements. The $40,000 facade, designed in 1922, is a picturesque feast, quite appropriate for Sartori, whose well-known restaurant, Joe’s, was a prime meeting place for political and civic figures.

That’s right: here on Nevins Street you could indeed “eat at Joe’s.” The cat silhouette on the chimney is a nice touch.

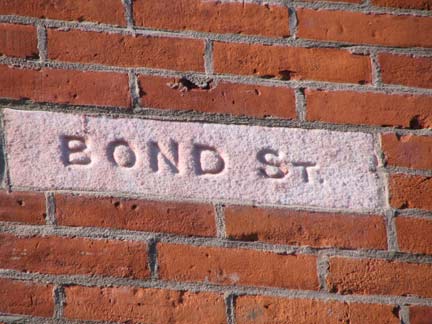

The Hoyt and Nevins families were early (1800s) landowners in the area and when two major north-south streets were cut through they were given their names. I can’t find an origin for Bond Street, between Hoyt and Nevins, though Bond Street (Old Bond and New Bond) is a major shopping street in Mayfair, London, England; Brooklyn’s Bond Street was so named by 1855 and perhaps was influenced by the London counterpart.

Livingston Street parallels the Fulton Mall before running into Flatbush Avenue, and is a major business street in its own right. This building at the NW corner of Nevins and Livingston has attractive terra cotta accents.

The Willie is framed perfectly looking east on Schermerhorn Street from Nevins. Brothers Peter and Abraham Schermerhorn were early 1800s merchants in downtown Brooklyn; when Green-Wood Cemetery was instituted in 1838 much of the land was purchased from them. Abraham’s daughter married into the Astor family. The correct pronunciation is Sker-mer-horn, though many Brooklynites have had trouble with it, saying Skrimmer-horn instead. Until recently the stretch was rather nondescript, but high rises have started sprouting on it of late.

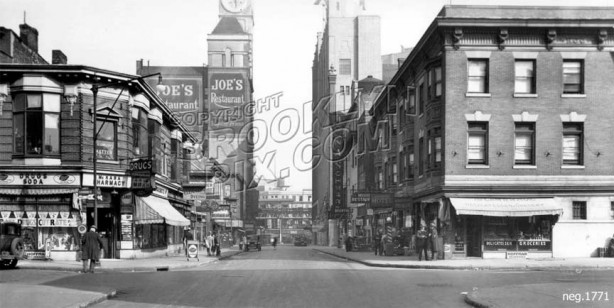

Nevins Street, looking north from Schermerhorn, 1929. The buildings in the foreground were torn down decades ago, but Joe’s and the Smith, Gray clock tower are visible in the background. brooklynpix

The handsome brick building at 50 Nevins Street (at State Street) is home to the Institute for Community Living and Broooklyn Psychosocial Rehabilitation Institute, treatment and residential programs for people with mental illness. Until I’m crazy enough, I’ll admire the building from the outside with its impressive arched entrance, window lintels, and masoned plaque explaining that Fort Masonic formerly stood here, one of the many fortifications erected in NYC in anticipation of a British invasion during the War of 1812. The tablet was placed on the centennial of the fort’s institution when the building was constructed.

It was one of a line of defenses including Fort Green (near the site of, but not the same as, the Fort Greene built during the Revolutionary War), Fort Cummings (DeKalb Avenue and Bond Street), Fort Swift (Atlantic Avenue and Court Street). Details on these 1812 fortifications at the link above.

None of these old forts has left any trace — but a War of 1812 blockhouse still stands in Central Park.

Nevins Street, looking north from State Street. A new tower has replaced the Smith, Gray clock tower — one of many new high rise apartment buildings going up on Flatbush Avenue extension. The street sign at right honors a couple that helped revive State Street from the moribund condition that had enveloped it after crime increased exponentially of the 1960s. They moved into a townhouse at 420 State in 1973; they were killed in a gas explosion there in 2000.

@ State Street and Nevins. One of the few remaining curved-mast lampposts remaining in NYC; looking east on State Street toward the bank tower.

I’d like to know more about this carriage house on the east side of Nevins between State Street and Atlantic Avenue. It has been renovated recently, that changed its previously bright white paint scheme to brown. RIGHT: 87 and 89 Nevins, between Atlantic and Pacific. Very interesting front rooms behind 30 windowpanes, from the looks of things.

Nevins and Pacific. This is the edge of the Boerum Hill Landmarked District, which I didn’t have time to investigate much — it’s a small area comprising Pacific between Bond and Nevins, Dean between Hoyt and Nevins, and Bergen between Hoyt and Bond, with parts of Bond and Hoyt thrown in. You can read all about it in the 1973 Landmarks Preservation Commission report. Right: Nevins Street chiseled sign, hanging in there.

Nevins between Baltic and Butler. A hopeful sign; the Gowanus Canal Pumping Station building (constructed 1911); and the Wyckoff Gardens housing project, located between Nevins and 3rd Avenue and Wyckoff Street and Baltic. The project is relatively new — built in 1966.

(In my humble opinion) Boerum Hill’s projects, Wyckoff Gardens and Gowanus Houses (see below) now serve as a check to gentrification, keeping the really big money out. I believe Red Hook Houses has also had the same effect in that neighborhood. In Fort Greene, the Ingersoll and Walt Whitman Houses also were a barrier for many years, but their presence has not stopped the high rise proliferation along Flatbush Avenue Extension or the upscaling of Fort Greene.

West on Butler now. There’s a brick building on the north side of the street, with the usual architectural flourishes that were commonly provided in the late 18th and early 20th Centuries, marked “The Rogers Memorial” and the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals symbol of an angel preventing a cartman from whipping a horse. The organization was founded by Henry Burghin 1866 (Burgh is interred in nearby Green-Wood Cemetery). In addition, a now-concrete filled horse trough marked “Presented to the ASPCA by Edith Bowdoin 1913” sits in front of the building. Three such troughs donated by Miss Bowdoin remain in NYC: here; in the traffic island at Northern Boulevard and Linden Place in Flushing, Queens; and (the only one still fulfilling its purpose) at 5th Avenue and East 60th Street, Central Park. Miss Bowdoin, in a letter to the New York Times May 1st, 1907, wrote:

“The [ASPCA] … hopes and expects to obtain the permission of the Art Commission to erect a large number of simple, inexpensive drinking troughs in the most congested sections of the city where they are most needed… It does not seem possible that the animal-loving people of New york will fail to respond liberally to this appeal on behalf of the faithful animal from which mankind derives so many benefits.”

More on the ASPCA’s early days:

Although the ASPCA’s early efforts focused on horses and livestock, the society worked for cats and dogs, too. Some cases were prosecuted. As published in the ASPCA’s first annual report in 1867, David Heath was sentenced to ten days in prison for beating a cat to death. Upon hearing the verdict, “he remarked that the arresting officer ought to be disemboweled,” at which point a $25 fine was added to his punishment.

Canines seemed to be most cruelly exploited as prize fighters. As the headline in an article appearing in the Long Island Star, December 8, 1876, read, “Two Bull Dogs Chew Each Other Up.” Attended by prominent betting men, the $1,000 championship fight lasted nearly four hours.

The ASPCA waged an all-out war on the day’s most famous “sportsman,” Kit Burns; on one occasion evoking high drama, Bergh dropped through a skylight into Burns’ pit. The battle was frequently frustrating, as judges read the law regarding dog fighting quite narrowly, making it almost impossible to convict someone unless they had been caught setting the dogs at each other or instigating the fight. ASPCA

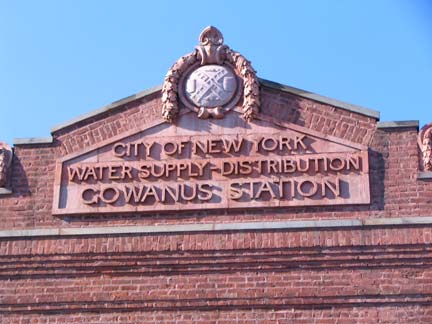

Gowanus Canal ends at Butler Street, and this is the location of its water filtration and pumping station. From FNY’sGowanus Canal page:

As far back as the 1880s the Gowanus Canal had become the cloaca of Brooklyn, filled with industrial waste, garbage and sewer outflow. Engineers reached a partial solution by 1911, when a flushing tunnel was dug from the head of the canal at Butler Street (above) southwest to Buttermilk Channel. At the pumping station a steam-powered propeller forced water out of the canal and expelled it into the channel, and cleaner water was admitted into the canal.

Things went, while not literally swimmingly, well enough for a few decades, though the Gowanus Canal would never remind anyone of Venice. The Buttermilk Channel (named because currents would cause milk to change to butter on boats moored there, supposedly) was not the place to deposit raw sewage, which would still find its way into the canal. The flushing tunnel stopped working altogether in the 1960s and it would be fully three decades before it would be repaired; Gowanus Canal became just as foul as before. Typhoid and cholera germs were found in it, prompting the construction of a Red Hook waste water treatment plant eventually constructed in the Brooklyn Navy Yard.

At last, though, the flush pump was repaired in May 1999–after 2000 tons of contaminated mud was dredged from the canal — and the Gowanus is on the (excruciatingly slow) way to cleanliness and wildlife has returned to its waters.

The looming presence of the Gowanus Houses, complete with water tanks that look like observation towers, have not deterred new construction from coming to nearby Warren Street just off Bond. Actually I don’t mind the new metal and glass-fronted condos — only when they appear on blocks otherwise dominated by 1890s-1910s brick townhouses that they in no way resemble.

On Bond between Wyckoff and Pacific, you will find some of the well-kept attached brick townhouses that earned Boerum Hill its LPC designation. Most were built between 1853-1870. You’ll also find a free-standing frame house or two, such as 143 Bond (lower left).

Building on Bond, a corner restaurant/pub at Pacific Street, is emblematic of the recent trend to not mark, or mark very inconspicuously, the name of the establishment (here, it’s on the chalkboard).Chumley’s, the rebuilding former speakeasy in Greenwich Village, began the trend several decades ago.

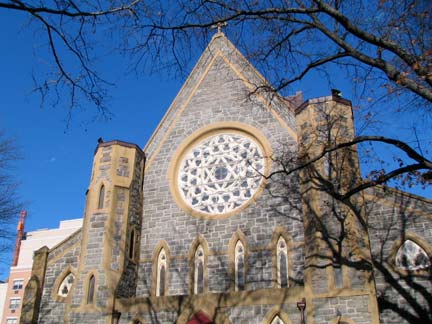

Two vintage houses of worship line up near each other on Atlantic Avenue at Bond Street: On the left, the Belorussian Autocephalic Orthodox Church, originally St. Peter’s Episcopal (1902) and on the right, originally the Swedish Pilgrims’ Evangelical Church (1903) now House of the Lord Church, ministered by the occasionally controversial Rev. Herbert Daughtry.

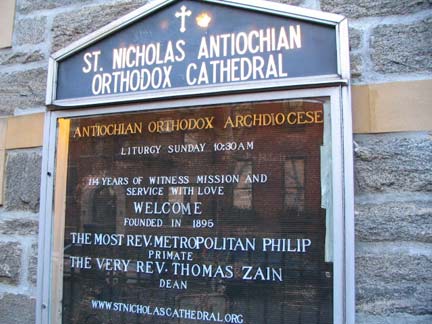

The ashlar-walled St. Nicholas Antiochan Orthodox Cathedral, State Street just west of Bond. If you think that’s a mouthful you should hear it in Greek. The Cathedral was built in 1895.

Behind the church’s parking lot, fronting on Bond, is what must be Brooklyn’s biggest brick wall unsullied by a window. This thing is impressive.

Between State Street and Fulton, Bond Street is pretty boring, except for the looming awesomeness of the original Brooklyn Dime Savings Bank at 9 DeKalb Avenue. From FNY’s Albee Square page:

The Dime is an Ionic-columned neo-Classical palace built between 1906 and 1908 by architects Mowbray and Uffinger. The interior is one of Brooklyn’s most magnificent indoor spaces: the central dome is defined indoors by a ring of twelve marble Corinthian columns crowned, at the top, by gilded representations of the obverse and reverse of the “Mercury” Dime. Since “Mercury” dimes were issued between 1916 and 1945 these must have been added sometime after the bank was opened in 1908.

The Albee Square Mall, which had been built in 1977 to replace the previous occupant of the space at DeKalb Avenue and Fulton Street, the Albee Square Theatre (you can see both at the above link) has given way to a hole in the ground in 2009, as the foundation is prepared for a new skyscraper, a mixed-use retail/residential/office building. Until it actually goes up, a view of three other gargantuas can be had from Fulton and Bond: 4 Metrotech Center, the Oro (cleverly named because it’s on Gold Street) and the riveting (and literally riveted) Toren Condo at Myrtle Avenue and Flatbush Extension. I couldn’t resist another shot of the Dime. It was recently Washington Mutual — I wonder what bank is there now.

Liebmann Building, Fulton and Hoyt Streets, constructed 1888; other three: the magnificent Wechsler Brothers Block a.k.a Offerman Building; the ground floor is being reconstructed yet again (for the previous appearance see FNY’s Fulton Street page) constructed by Lauritzen and Voss 1890-1891. Though the building is marked “Offerman Building” above the second floor, stylized H’s also appear on the sides.

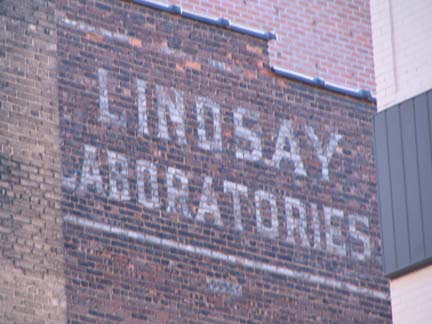

Heading south again, this time on Hoyt, the aggressively Deco 1929 Abraham & Straus, now Macy’s department store facade at Livingston. A&S, founded in 1865 and folded into Macy’s in the 1990s, was/is an amalgamation of 8 different buildings between Hoyt Street, Gallatin Place, and Fulton and Livingston Streets. Also on Livingston, you’ll find ghost wall dog ads for several now-forgotten enterprises.

The rather forbidding entrance to the IND Hoyt/Schermerhorn A, C, G lines rests below what used to be Loesser’s Department Store, and “L” signs can still be found within. Note the new bike lane/bike parking area in front.

Though Schermerhorn Street is now reinventing itself as rich condo heaven, I hope the crack de …ah, hot sheets palace the Prince Hotel will survive to meet the needs of various area residents.

While Victory, at Hoyt and State (note the name on the chalk board a la Building at Bond, above) boasts a classic chrome exterior, it’s not a diner in the true sense — there’s only room for about 5-10 to sit inside, and the menu is limited to breakfast items, coffee, empanadas (stuffed pastries) and sandwiches. They have earned good reviews and have been a mainstay for several years.

I know little about 75A and 75B Hoyt, between State and Atlantic, other than the building is quite old and I enjoyed the magenta and yellow treatments on the front doors.

148 Hoyt Street at Bergen, one of Boerum Hill’s masterpieces. According to the Boerum Hill LPC designation report, it was constructed in 1851 and underwent renovations in 1881 that gave it its present appearance. The windows that face out over the street are known as oriels.

The Brooklyn Inn, which occupies the first floor, has been there for a few decades and boasts an oak bar dating from the 1870s. Its manager, Jason Furlani, has been famously touchy with bloggers such as Curbed’s Lockhart Steele [Eater]. The Inn was locked the day I went past, but Brooklyn The Borough will show you the interior.

Late day sun hits these two-story brick buildings just right on Hoyt between Douglass and DeGraw.

The imposing Italian Renaissance 421 DeGraw Street used to be the elementary school attached to St. Agnes Church (see below). It was converted into a 90-unit apartment building in 1999 — it had been vacant for 12 years before that.

St. Agnes Roman Catholic Church, Hoyt and Sackett Streets, was dedicated in 1888 by Brooklyn’s Bishop John Laughlin. Among the biggest Catholic churches in Brooklyn, its medieval Gothic Newark stone gargoyled tower is 130 feet tall and the nave is 174 feet in length. 20 stained glass windows, imported from Munich, Germany, depict the life of St. Agnes of Rome.

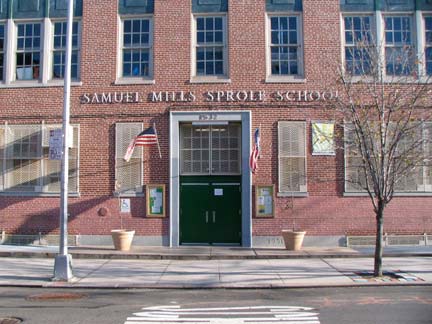

PS 32, the Samuel Mills Sprole School on Hoyt between Sackett and Union, was built in 1951,replacing an older building on the same spot. Sprole was principal of PS 32 between 1873 and 1905.

Treading dangerously into Carroll Gardens territory, #327-333 Hoyt (above left, 327 and 329) were built in 1869, the oldest houses in the district, which has also received LPC designation. I wonder if the street signs on the side of the building are the originals.

Looking down Carroll Street we see the venerable Carroll Street Bridge (1889) and the spires of St. Francis Xavier and Old first Reformed Churches (seen in greater detail on FNY’s Carroll Street Slice).

Carroll Street, looking toward a row of 1874 brownstones on Hoyt.

Time to kick it in the head and take the F train back, but Carroll Gardens is on the radar for a future FNY profile.

12/14/09