Up until a couple of years ago, Anna Huntington’s Joan of Arc statue on Riverside Drive and West 93rd Street was the only one depicting a historic female personality.

And, up until a couple of days ago, I thought it still was*. I was rolling past Frederick Douglass Boulevard and West 122nd Street, where they meet St. Nicholas Avenue, a couple of days ago in a bus and spotted what you see above, and the following day returned and got a better look. The statue depicts Underground Railroad figure Harriet Ross Tubman, the first formal memorial in the city dedicated to her (although Brooklyn’s Fulton Street has been subtitled Harriet Tubman Boulevard for most of its length).

*A statue of Eleanor Roosevelt is tucked away at Riverside Drive and West 72nd Street; Golda Meir is in the Garment District; and Gertrude Stein is in Bryant Park

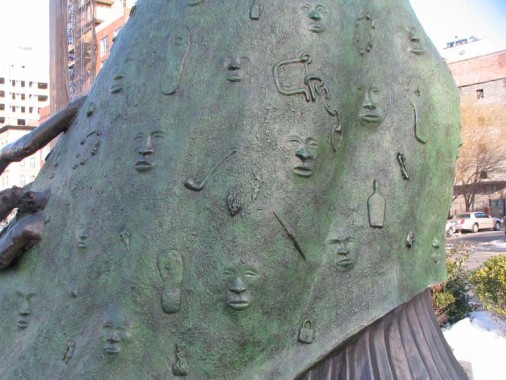

The statue, by sculptor Alison Saar, subtitled “Swing Low,” was dedicated on November 13, 2008 and features a newly lanscaped triangle that includes plantings from both New York and Tubman’s home state of Maryland. The back of the sculpture depicts stylized roots that are being pulled form the ground by Tubman’s resolute stride.

Born into slavery in Bucktown, Maryland, Tubman escaped her own chains in 1849 to find safe haven in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. She did so through the underground railroad, an elaborate and secret series of houses, tunnels, and roads set up by abolitionists and former slaves. “When I found I had crossed the [Mason-Dixon] line, I looked at my hands to see if I were the same person, ” Tubman later wrote. “. . . the sun came like gold through the tree and over the field and I felt like I was in heaven.” She would spend the rest of her life helping other slaves escape to freedom.

Her early life as a slave had been filled with abuse; at the age of 13, when she attempted to save another slave from punishment, she was struck in the head with a two-pound iron weight. She would suffer periodic blackouts from the injury for the rest of her life.

After her escape, Tubman worked as a maid in Philadelphia and joined the large and active abolitionist group in the city. In 1850, after Congress passed the Fugitive Slave Act, making it illegal to help a runaway slave, Tubman decided to join the Underground Railroad. Her first expedition took place in 1851, when she managed to thread her way through the backwoods to Baltimore and return to the North with her sister and her sister’s children. From that time until the onset of the Civil War, Tubman traveled to the South about 18 times and helped close to 300 slaves escape. In 1857, Tubman led her parents to freedom in Auburn, New York, which became her home as well.

Tubman was never caught and never lost a slave to the Southern militia, and as her reputation grew, so too did the desire among Southerners to put a stop to her activities; rewards for her capture once totaled about $40,000. During the Civil War, Tubman served as a nurse, scout, and sometime-spy for the Union army, mainly in South Carolina. She also took part in a military campaign that resulted in the rescue of 756 slaves and destroyed millions of dollars’ worth of enemy property.

After the war, Tubman returned to Auburn and continued her involvement in social issues, including the women’s rights movement. In 1908, she established a home in Auburn for elderly and indigent blacks that later became known as the Harriet Tubman Home. She died on March 10, 1913, at the approximate age of 93. Civil War Home

Saar depicted anonymous faces of those aided by Tubman and the Underground Railroad (inspired by African masks), along with symbols of the destroyed system of slavery such as broken chains and locks.

The only complaint I would have with the statue was Saar’s decision to depict Tubman’s eyes without pupils, which makes her look anonymous.

In the 1980s, 8th Avenue north of West 110th Street was renamed for orator, abolitionist and author Frederick Douglass. Few reminders of the former name remain, with the exception being the 8th Avenue Deli opposite the Tubman Memorial.

Frederick Douglass, writing a letter in support of a biography of Harriet Tubman in 1868:

You ask for what you do not need when you call upon me for a word of commendation. I need such words from you far more than you can need them from me, especially where your superior labors and devotion to the cause of the lately enslaved of our land are known as I know them. The difference between us is very marked. Most that I have done and suffered in the service of our cause has been in public, and I have received much encouragement at every step of the way. You, on the other hand, have labored in a private way. I have wrought in the day — you in the night… The midnight sky and the silent stars have been the witnesses of your devotion to freedom and of your heroism. Excepting John Brown — of sacred memory — I know of no one who has willingly encountered more perils and hardships to serve our enslaved people than you have.

Page completed February 17, 2010