BY SERGEY KADINSKY

Contributor to Forgotten NY

Queens is a borough of many boulevards. Some define the borough, while others stretch for only a few blocks, stubs of once-grand plans that never came to fruition. Astoria’s Berrian Boulevard is one such example. When Queens was mapped out into a uniform grid in the early 1920s, this road was supposed to mark the borough’s improved northern shore. Instead of bays and inlets, a straightened shoreline between Astoria and Flushing would be lined by this boulevard. But the construction of power plants, a sewage treatment plant, and an airport, kept that plan from becoming reality. Still, the boulevard’s name has history, hearkening back to a local landowning family and an island that has since been fused to the mainland.

Anyone who has walked Steinway Street is familiar with its shopping district and Middle Eastern food, but its northern end is empty, with only the humming of the power plant to keep a company for a lone pedestrian.

The northern shore is out of view, blocked by the sewage treatment plant. While the shoreline of Manhattan is ringed by a bike trail, most of the Queens shoreline is restricted to the public.

Civil liberties are put to a test because security cameras are everywhere, as are signs prohibiting photography. Looking westward, a power plant frames the boulevard.

How it All Began

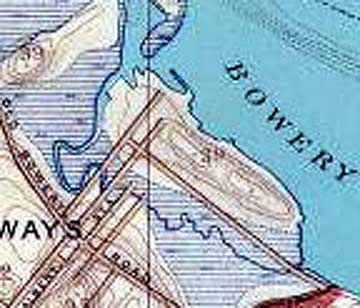

This 1891 Julius Bien topographic map of Queens shows the largely undeveloped landscape of the northern shore. The boulevard’s namesake island sits just off the coast. Like The Bowery of Manhattan, Bowery Bay also took its name from the Dutch term bouwerij, or farm. Today, there is still one colonial-period farmhouse standing near its shore, but more on this later. Another Dutch name on the map is Rikers Island, which was later expanded with landfill to form the nation’s largest urban prison complex. Lawrence Point later became a power plant campus, and Sanford Point briefly served as an amusement district before being swallowed up by LaGuardia Airport.

Closer detail shows a second island, created during high tides. Luyster Island was also named after a Dutch colonial family. The island’s main road is today’s 19th Avenue.

The first European settler here was Hendrick Harmensen in 1638. He was killed by local natives in 1643. His widow remarried, and the island was briefly called Houwclicken (Dowry Island). The deacons of the Dutch Reformed Church bought the farm before 1654, to establish maintenance for their poor, hence it was called “Armen” or “Poor Bowery.” That’s how Bowery Bay got its name.

About 1688, the church sold its farm to Pieter Cornelissen Luyster, who lent his name to the Dowry Island and Luyster Creek.

The Island Disappears

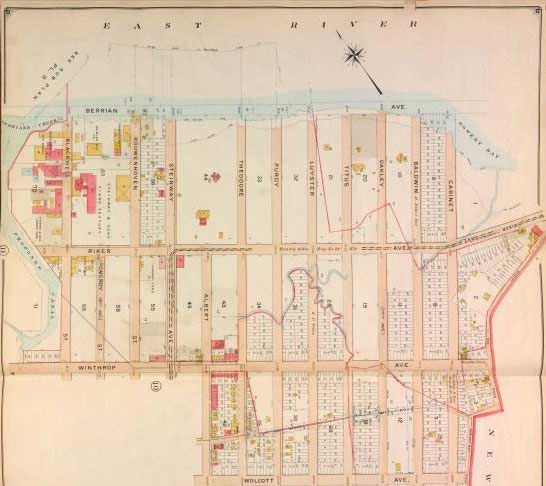

This 1891 property map has the unspoiled topography above delineated into a street grid. The western end of Luyster’s Creek is straightened into a canal, while the rest of it appears buried by street grid. The pink-colored campus on the former island’s western edge is the Steinway piano manufacturer, which remains there today. Along the shoreline, Berrian Boulevard is proposed as the northern limit of development. The two-block wide property between Steinway and Theodore Street is the Steinway Mansion.

There was a time when the northern shore of Queens was the western extension of Long Island’s Gold Coast, lined with summer mansions of the rich and famous. The upper East river was often labeled by mapmakers as part of Long Island Sound. On the eastern edge of the map, another pink building is the Lent-Riker-Smith farm, which gives its name to old Riker Avenue. After the grid was assigned numbers, it became 19th Avenue.

North of Ditmars Boulevard, the landscape was mostly flat marshlands, with a few hilltops poking up. These hilltops were crowned with mansions and summer homes, overlooking the bend in the East River.

The Steinway Mansion

The most important historic structure in this area is the Steinway Mansion, a lone dwelling on a hilltop, surrounded on all sides by industry. To an unaware visitor, the patch of green amid industry could be reminiscent of actor Chevy Chase’s 1991 visit to Valkenvania, but it is more of a curiosity than a menace.

As the neighborhood industrialized, the estate was divided and auctioned off. While all local streets were widened and hills flattened, the Steinway property kept its pre-industrial charm.

Tailor shop owner Jack Halberian, an Armenian immigrant from Turkey, bought the mansion for $45,000. His son Michael is the current owner. With age, Halberian is finding it more costly to keep the landmark house in shape, and is currently seeking a buyer for the 27-room home, either as a residence or a public museum. During Halberian’s stewardship, the home received a billiard room, basement bar, and a Roman bath.

Built in 1858 as a summer home for downtown Manhattan optician Benjamin Pike Jr, the Italianate-style home took on a collection of globes, telescopes, and similar visual aids. He died in this home in 1864. Within a decade, local manufacturer William Steinway bought it, and his family lived here until 1926.

In October 2010 City Councilman Peter Vallone and Michael Halberian hosted an open house for potential buyers and anyone else interested in the history of the Steinway Mansion.

“I have asked the mayor to come here personally to take a tour of the house,” Vallone said. “If we gain support from the city, then we can build a foundation to make this amazing home into a museum or a major neighborhood resource.” As visitors gathered on the front lawn, Bob Singleton of the Greater Astoria Historical Society (above), spoke about the history of the home and the significance of William Steinway to Astoria.

“Steinway helped to build this town and make it what it is today,” Singleton said.

Guests viewed every room of the 12,285-square-foot mansion which features original ornate moldings and coffered ceilings, six original wood-burning fireplaces, original plank hardwood floors, four full bathrooms, a half-bathroom and five bedrooms. Basement accommodations include a recreation area complete with English pub, billiard room, sauna and Jacuzzi.

The centerpiece of the home, built in 1858 by Benjamin T. Pike Jr., an optician who died in the house in 1864, is the library that Halberian has filled with antique books that cover the history of New York and Queens. Queens Gazette; photos : Jason Antos

Steinway brought his factory to Astoria in 1870, seeking to escape the labor unrest of lower Manhattan. Countering the labor organizers, he sweetened the deal for his workers by building a 400-acre neighborhood for them. To this day, the majority of Steinway’s employees live in the neighborhood. And the company? So far, there are no signs of any overseas move by Steinway. On the right above, an old fire alarm signal graces the pole across the street from Steinway.

A part of Astoria, many maps and locals dub this sub-neighborhood as Steinway, because it was built by the piano maker.

This map from Greater Astoria Historical Society shows an outline of Steinway. Berrian’s Island would later be fused to the mainland, its name transferred to the proposed shoreline boulevard. The curvy Bowery Bay Road continues to defy the grid as today’s 20th Road.

The islands of Wards and Randalls have been fused together by landfill since the early 1960s, but the island park continues to use two names. The city never decided which of the two names should be dropped from the map.

Luyster’s Creek

Fed by storm sewers and ringed by power plants, Luyster’s Creek is blissfully empty. With security all around, there are no boats in this stream, and hardly any fish, either. The land on the left side of the creek was once Berrian’s Island. It too has since been merged to the mainland. Considering the surroundings, it’s wise to obey the “no swimming” sign.

The brick patterns on this 19th Avenue building are reminiscent of a Joan Miro painting in style, and the NY Hall of Science bricks in appearance.

The Bowery Bay wastewater treatment plant has been keeping the local water clean since 1939, sitting atop the former Luyster’s Island.

Curved corners, striped bricks, and geometric patterns define its style, which was popular before the Second World War. Sewage treatment plants may not have many fans, but there is a local Art Deco Society to promote the prewar style.

The workers are a fun group, competing against other local sewage plants in demonstrating their expertise and skills. This plant’s team is called Bowery Bay Bowl Busters. The citywide winner goes on to compete in the national Operatorís Challenge, a competition sponsored by the Water Environment Federation.

A dense hilltop occupies a 5-block parcel owned by the Port Authority. A former landfill, the waterfront forest blocks views of Rikers Island. The area is part of an industrial business zone, off-limits to condo developers for now.

Welcome to Rikers Island

Since 1932, Rikers Island has housed the city’s prisoners. Politically in the Bronx, but its addresses, zip code and bridge, all connect to Queens. The final block of Hazen Street begins with an imposing sign, fences, lights, checkpoints, and almost-a-mile-long bridge to the island prison. I did not venture too close to the first checkpoint, lest my camera is confiscated.

The inmates of Rikers are those serving a year or less, or on temporary sentences. for harsher sentences, they are sent “up the river” to upstate prisons. Many of the buildings on the island are named after past wardens and correction officials. The island also contains a cooking school, ball fields, grocery stores, barbershop, power plant, print shop, chapel, car wash, and a small farm!

The western third of the island is natural, but most of Rikers sits atop landfill deposited in the 1950s. On the northernmost point, a ferry landing deposited inmates prior to the bridge’s opening. At times, retired Staten Island Ferry boats were docked there as prison barges, used to relieve the crowded conditions on the island.

Either way, part of the punishment includes having to put up with noise from airplanes landing and taking off from nearby LaGuardia Airport.

The Lent-Riker House

Returning to the mainland, there is a colonial-period farmhouse dating to 1656, and like the Steinway Mansion, this old house is still privately owned and used as a residence. Since 1979, the home and its backyard cemetery have been restored and maintained by current owners Michael and Marion Smith. We’ve been here before, and the Smiths also have a website on their home’s history.

The Elmjack Little League has a sliver of the shoreline between the Rikers Island approach and the airport. The land is owned by the Port Authority and leased to the little league. Its name is an acronym of the Elmhurst and Jackson Heights neighborhoods.

Astoria Heights is a charming enclave of Tudor-style homes and curving streets brings an end to 19th Avenue, as it hits the airport. Nearby, the street grids of Astoria and Jackson Heights collide, separated by Hazen Street. Prior to 1898, these modern-day neighborhoods respectively belonged to Long Island City and the village of Newtown. Today, both are part of greater New York City.

Taking Flight

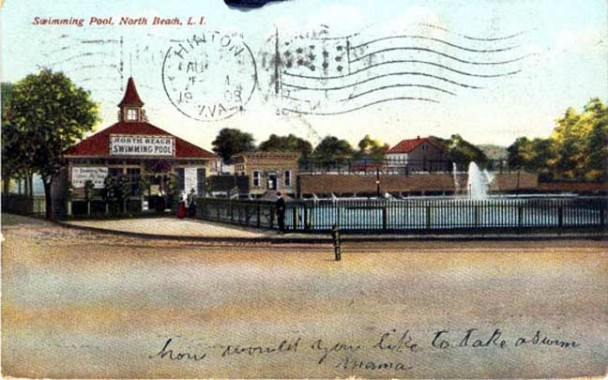

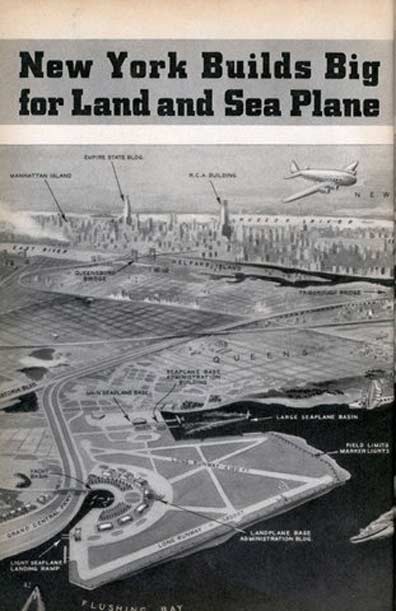

The amusement district of North Beach once ringed Bowery Bay and Sanford Point, but in 1929, the Glenn H. Curtiss Airport moved in, muscling out the resort community. In 1937, the city took over the airport, purchased additional land around it, and expanded it into the East River. Two years later, LaGuardia Airport opened, with seaplanes on Bowery Bay’s Marine Air Terminal, and two long runways for airplanes. The airport’s proximity to Manhattan made it an instant success. Within a year of its opening, it took the record as the world’s busiest commercial airport.

As mentioned earlier, Berrian Boulevard is only 4 blocks long, but it was supposed to line the shore, as this 1920s map shows. Ironically on this map, the dotted line was built, while the solid section of the boulevard was not, occupied by the airport. Cutting across the grid is Astoria Boulevard, an ancient road connecting Astoria to Flushing. Trains Meadows, a long-forgotten area no longer appears on today’s maps, replaced by East Elmhurst.

ADDITIONAL RESOURCES:

For more on the history of Rikers Island, visit the NY Correction History Society

The Lent-Riker-Smith House is sometimes open to the public, check its site for tour dates

Neighborhood tours are also provided by Greater Astoria Historical Society

SOURCES:

“Visitors get inside look at Steinway mansion” by Rebecca Henely. YourNabe.com 10/14/10

“Pols may be key to getting city to buy Steinway Mansion” by Leigh Remizowski NY Daily News 9/29/10

“If You’re Thinking of Living In/Steinway, Queens” by Diana Shaman, NY Times 3/2/03

“Steinway & Sons” by Robert K. Lieberman. Yale University Press 1995

Sergey Kadinsky has been living in Queens since age eight. His interest in journalism can be traced back to childhood, when he made a hobby out of writing letters to the editors of local newspapers. He is a writer who aspires to a career in journalism and politics. At times, he has been spotted giving tourist-friendly monologues atop Gray Line buses. He also paints murals that contain maze puzzles. His website is mazeartist.

Page completed October 20, 2010

Your webmaster Kevin Walsh: erpietri@earthlink.net

©2010 FNY

1 comment

[…] fun note, from Forgotten NY, is that the whole treatment plant sits atop the former Luyster’s Island, another sign of the […]

Comments are closed.