Welcome to the inaugural page in the latest FNY category, the second added in the past two years, following FNY Walks in 2010. In FNY Roads I’ll be concentrating on one one road or street per page, walking it end to end, or alternately covering an ancient NYC road of which only short pieces remain. In the past such treatments have been lumped into Street Scenes, but that category had hundreds of entries, and I had to find a way to not add so many. I tend to think of FNY now as pre-heart surgery and post-heart surgery, at risk of making it sound too personal, and today’s scenes on Vanderbilt Avenue were taken in April 2009, just before my successful operation to replace an aortic valve; I wouldn’t get back to full speed for an entire year, since a dislike of repetitive motion in palaces of perspiration and a predilection for pizza have doomed me to a perpetual existence of being out of 100% conditioning. I seem to be at full speed again, and will be Forgottening until the next health scare.

Vanderbilt Avenue, named for Cornelius Vanderbilt, the original ferry operator between Manhattan and Staten Island and later, a steamship and railroad magnate (and great-great-great grandfather of TV newsman Anderson Cooper) runs from Flushing Avenue and the Brooklyn Navy Yard south to Grand Army Plaza, where Flatbush Avenue meets Prospect Park. It is one of the main spines of Clinton Hill, a prime Brooklyn neighborhood boasting major architectural treasures (many of which are on Clinton Avenue and will have to wait for another page to be featured). North of Atlantic Avenue, it is paralleled by Clermont Avenue, the name of Robert Fulton’s famed steamship, and Clinton Avenue: the street was likely named for DeWitt Clinton’s involvement in the construction of the Erie Canal, as men who had a hand in NYC’s waterborne growth, and the instruments of that growth, are honored in this region.

Note: The Clinton Hill LPC Report states that Vanderbilt Avenue is named for a Vanderbilt scion, local landowner John Vanderbilt.

Vanderbilt Avenue runs through the neighborhood of Prospect Heights, the rhomboid defined by Flatbush Avenue, Eastern Parkway, Atlantic Avenue and Washington Avenue.

Beginning at the south end of Vanderbilt at the Soldiers and Sailors Arch, the bust of gynecologist Alexander Skene and some vintage old-style park benches. The Who Are Those Guys? of Grand Army Plaza are named on this FNY Slice. Plans are afoot to reroute traffic to make GAP safer for pedestrians and bicyclists.

This streamlined Moderne building at Vanderbilt and Plaza Street East (Plaza Street encircles Grand Army Plaza except for the part occupied by Prospect Park) was likely built in the early 1930s.

249 Sterling Place (at Vanderbilt) is an historic landmark completed between 1867-1869 with an 1887 addition. When originally constructed, the building served as Public School Number 9: it is now PS 340.

The PS 9 Annex, 251-279 Sterling Place, was completed in 1895 by architect James Naughton. It was designated a NYC Landmark in 1987 and had been rehabilitated as artists’ housing by 1990. Brownstoner has a look at the interior of one of the apartments. It’s perplexingly difficult to glean information on NYC public school buildings, so if anyone knows anything more about this magnificent building let me know.

673-679 Vanderbilt. This row of Romanesque/Renaissance Revival style flats buildings was designed by architects Dahlander & Hedman and built c. 1895 by builder William Reynolds at a time when multiple dwellings were gaining favor among developers due to increases in population and property values in greater New York. Unlike other buildings on Vanderbilt Avenue in the Prospect Heights historic district, these flats buildings were not built with commercial ground stories. Prospect Heights Landmarks Preservation Commission Report [q.v. for a description of every building in the district]

633-639 Vanderbilt, east side between St. Marks Avenue and Prospect Place, built 1872. Occasional stretches of Vanderbilt Avenue now have a center median, traffic bollards, and newly planted trees that will reach maturity in 25-30 years.

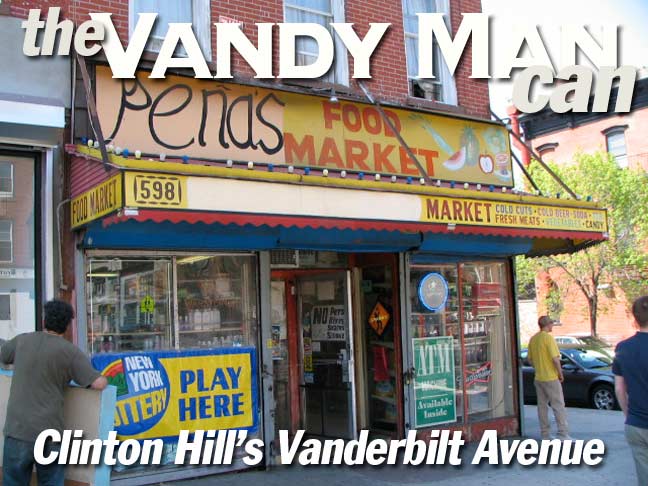

Vanderbilt Avenue became a major commercial thoroughfare in the late 1800s, and a burgeoning restaurant/bar scene has popped up in the early 21st. Soda Bar, between St. Marks and Prospect, began life as a soda fountain in the 1930s. Pena’s Food Market, St. Mark’s, is a holdover from the pre-gentrification era.

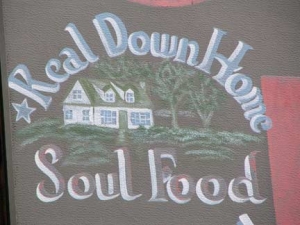

The story in Prospect Heights and along Vanderbilt has recently been about gentrification and improvements, but I liked the handmade signs from a previous era, or at least harking back to one. These are hand drawn with a triangle, T square, mechanical pencil and paints as well as freehand calligraphy.

Prospect Heights and adjoining Fort Greene are bicycle hotbeds. At the risk of sounding like a disgruntled, middle-aged burnout (if the shoe fits wear it) when I was riding a bicycle more regularly, we never had bike lanes, painted in green, separated by curbs, or anything else. We sucked in exhaust and avoided doorers, got home in one piece, and went out the next day and did it again. I had no sense of entitlement and obeyed traffic regulations and stopped for pedestrians. But look who’s the sucker. At least I was born late enough to evade Vietnam.

Do I use Google Street View? You bet I do, and I enjoy it. Looking south from Bergen Street on Vanderbilt. When I was attending high school a couple of blocks away on Atlantic and Washington from 1971-1975, if you told me tour buses would someday be making their way along Vanderbilt, I would have called the men in the white coats. I enjoyed my high school years but it was quite insulated — we never strayed far from the place, which was a shame because I could have gotten started on Forgottening a lot sooner. For example, there were slaughterhouses and meat wholesalers on Atlantic Avenue in the Super 70s, and when walking on Atlantic, we often had to get around raw meat hanging from hooks. But that’s for another nostalgia page. In the 1970s, this was the Wild West. Different planet now.

The Hot Bird barb-b-que franchise ( I think it consisted of one restaurant anyway) clucked its last in the 1990s, leaving behind two large painted signs, one on a now-demolished building facing Vanderbilt at Dean Street, and the other on Clinton just north of Atlantic (left). However, the Hot Bird name was revived as a Clinton Avenue bar that opened in a former auto repair place:

Now the bird is back — in a way. An old auto shop beneath one of the yellow signs has been transformed into a new business. But the new Hot Bird will be a bar, not a chicken joint, says owner Frank Moe, who also operates the Fort Greene bar Rope. “Just because the location is right under the old sign, I decided to name it after that,” he says. WSJ

The signs’ directions will get you nowhere near the new Hot Bird! I love that name, Frank Moe. That’s the greatest name I’ve heard since the former Cramps drummer — Nick Knox.

Detoured down Pacific east of Vanderbilt to shoot St. Joseph’s Church and its school which, as the cornerstone says, were built in 1912, so the buildings will soon be celebrating a centennial. The parish was established in 1850 as a place of worship for immigrating Irish fleeing the potato famine of the late 1840s.

When I am in the area I always try to get at least a glimpse of my old high school, Cathedral Prep, a Flemish Gothic pile built in 1915 at 555 Washington Avenue at Atlantic. The school graduated its last class in 1985 but the building was resuscitated and rehabilitated as Cathedral Condominiums in the 1990s.

The Washington Avenue side play yard and faculty parking lot have now been buried under the Isabella Condominiums, constructed in 2008. Their website advertises a “virtual doorman.” Different planet since I was here!

Not sure about the fate of this loft building, magnificent in its blockiness, at the NW corner of Vanderbilt and Atlantic.

In residential architecture, glass is the new black, and Clinton Avenue north of Atlantic presents quite the contrast between housing styles of, say, the 1920s vs. that of the 2010s. I know this: the 1920s units were affordable for most tenants from the git-go, while units in the new high-rises aren’t. That said: I like the glassy residential style.

North of Atlantic Avenue Vanderbilt Avenue enters Clinton Hill, one of Brooklyn’s architectural wonderworlds. When I went to high school in the area it was stooped, bloodied, bowed, but still alive; it weathered the difficult era of 1960-1985 and has entered a new era of rehabilitation, exclusivity, and affluence. The neighborhood is home to Pratt Institute, one of America’s pre-eminent design schools, and St. Joseph’s College.

A complete description of Clinton Hill’s historic houses can be found in the comprehensive, though rather dry, Landmarks Preservation Commission Report.

Gateway Triangle, a small park formed by Fulton Street and Vanderbilt and Gates Avenues. The latter begins an east/northeast run that takes it to the heart of Ridgewood.

Several buildings on Vanderbilt Avenue are former stables, as are several on Waverly Avenue, two blocks east. In between is Clinton Avenue, built as the original main spine of Clinton Hill, which has the lion’s share of the neighborhood’s mansions. So, Vanderbilt and Waverly are where the nabobs parked their carriage steeds.

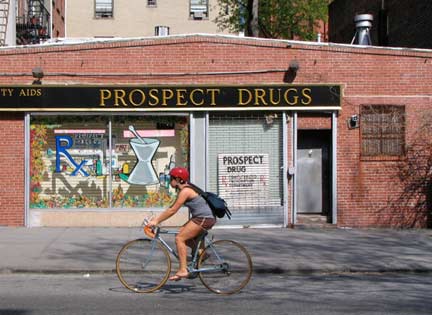

Prospect Drugs is so named in honor of Prospect Park, about one mile south on Vanderbilt Avenue. The peaked building it’s in has an exact twin across the street on Greene Avenue.

The northwest corner of Vanderbilt and Greene features Bishop Loughlin Memorial High School, an athletic rival of Cathedral in the good old days. The school was instituted as St. James School on Jay Street (under the auspices of what is now the St. James Cathedral) in 1823; in 1933, a new school was built here and dedicated to Bp. John Loughlin (1853-1991), the first Bishop of Brooklyn. Alumni include former NY Knick Mark Jackson (1983) and the only person I have voted for three times, Mayor Rudolph Giuliani (1961).

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle called Queen of All Saints one block north on Lafayette and Vanderbilt “one of the two or three most beautiful specimens of church architecture in the United States” when it opened in 1913. Like my own boyhood parish, St. Anselm in Bay Ridge, the church and school were combined in in one building. Architect Gustave Steinback used Sainte Chapelle, the 13th Century Gothic Paris chapel, as inspiration.

Queen of All Saints far surpasses Cathedral Prep in the sheer number of gargoyles. Interestingly, even bizarrely, waterspouts depicting angels or saints are side by side with the usual monstrous or demonic figures.

Looking north from Gates Avenue.

More Vanderbilt Avenue on Page 2