I have been to Cobble Hill and Carroll Gardens, the two neighborhoods just to the south of downtown Brooklyn, on numerous occasions, even covering Court Street on one FNY page, and shot Clinton Street in almost its entirety in the summer of 2010 — those photos have yet to be published. I have also covered Columbia Street, another parallel street, fairly thoroughly. You might say I have been here pretty frequently, it’s a pleasant part of town. One aspect of the region, though, I had never really explored, even when I lived in Brooklyn and bicycled all over, laying the groundwork for future FNY escapades. The Brooklyn-Queens Expressway was bruited through in the 1950s, long before this area acquired a vaguely hip atmosphere, when it was a working class neighborhood populated by factory and dock workers and their families.

The perfect prey for highway czar Robert Moses, who ran the expressway right through the center of the neighborhood, eliminating the west side of Hicks Street and pieces of several cross streets. The neighborhood was henceforth divided into pieces east and west of the expressway. Moses did make some concessions to the neighborhood, bridging the trench at Congress, Kane and Union Streets, and a pedestrian crossing at Summit. There have been recent rumblings about covering the trench and making it a true tunnel, overlaying it with parks and malls, but after Boston’s “Big Dig” experience, with costs reaching close to $1B and nearly two decades worth of construction, making the BQE a tunnel (its elevated run through Sunset Park has also long been a bone of contention in Brooklyn, and there have always been thoughts about tunnelizing that, too) will likely remain fantasies of developers.

So, on a chilly, mostly overcast day in March 2011 I decided to take a thorough look at the little pieces of cross streets that remained after the Moses whack job of the 1950s. Is west of the trench a different beast than east? Or have they evolved in parallel fashion?

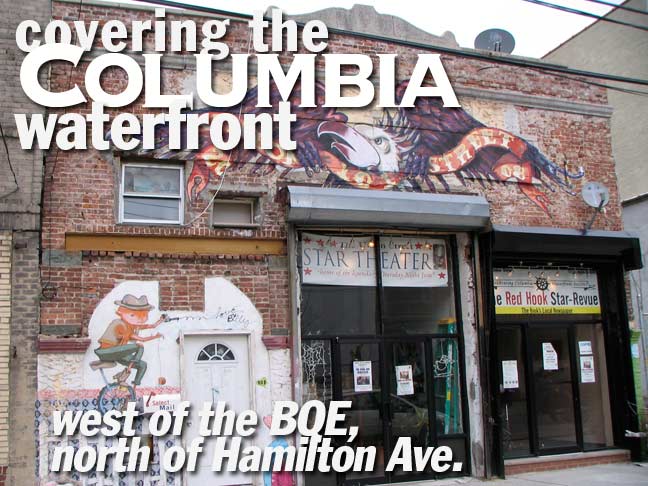

WAYFARING: COLUMBIA WATERFRONT

I crossed the BQE at Congress Street and walked south on the “new” west side of Hicks, built as a service road in the 1950s. The trench does give advantageous views to the distinctive buildings on the “old” east side of Hicks, such as a 2005 condo development by architect Robert Scarano called “The Arches at Cobble Hill” at 101 Warren Street, built in the shell of the existing 1858 St. Peter’s Church, Rectory and “Home for Working Girls.” At right is the massive yet humanly scaled and handsome Cobble Hill Towers, built as tenements by Alfred Tredway White in 1878-1879 as housing for laborers and middle class workers. White repeated the design in the Brooklyn Heights Riverside houses a few years later. When the White buildings opened, the 2-5 room apartments rented from $7.25 to $14 a month, or up to $250 in today’s money. Today, apartments in the Arches run over $1M, while some of the units in Cobble Hill Towers could be as much as $706,000.

Warren Street between Hicks and Columbia, the same brick attached buildings you see east of the BQE. Right, Columbia Street at Hicks. This is the only remaining working Brooklyn waterfront, save the Bush Terminal float barges in Sunset Park. Much of Red Hook’s waterfront has become parkland and retail while north of here, Furman Street was once a hotbed of shipping but has also become residential and parkland. Columbia Street has undergone a few years of construction that has added a bike path on its west side. The lack of tall buildings on Columbia allows a view of the Manhattan skyline.

Baltic Street at Columbia and just east. Baltic, like Union Street (see below) was named for massive warehouses, the Baltic and Union Stores, that once housed shipments from all the world over that came into NY Harbor on sailing ships. The dour buildings are administration buildings belonging to the Port Authority of NY and NJ. Along Baltic Street are newish brick buildings that were built with a last gasp of panache before the awfulness of modern multifamily residential architecture began to permeate in the 1990s.

Moving south to Kane Street, the block between Hicks Street and Tiffany Place is dominated by One Tiffany Place, a huge brickfaced loft turned residential–an ‘early adopter’ in 1986.

The building was a former factory used to create art by Louis Comfort Tiffany (1848-1933) the great decorative glassworks pioneer.

Passing this 1960s-themed Vokswagen bug wagon on Kane Street. I seemed to remember Ken Kesey and the pop-anarchist pyschedelicists Merry Pranksters driving a Volkswagen bus, but they ditched it early on and traveled in a school bus. On the other hand NY Songlines‘ Jim Naureckas told me that the spook-hunting Great Dane Scooby-Dooand his crew used a Volkswagen. In actuality they used a Ford Econoline as the Mystery Machine. Vans like this, though, have transported thousands of pot smoking hippies all over the country for decades.

Kane Street, looking at Columbia and the shipyards and a winter salt pile beyond, and then east toward Cobble Hill. Kane crosses the BQE on a traffic bridge. Until 1928 Kane Street was known as Harrison Street, but the name was changed to honor election commissioner, alderman (today that would be a City Councilman) and police sergeant James Kane (1839-1926). There was a different philosophy then about renaming streets. Until the 1980s or so, the name was changed, and that was that, but following the 1980s a street was not so much renamed as subtitled., i.e. both names would appear. I think the last time street names were just changed, with the old names wiped out and the new ones replacing them, were in the 1970s when 7th Avenue and 8th Avenues became Adam Clayton Powell Boulevard, Jr., and Frederick Douglass Boulevards. Of course the city ran into quite a bit of resistance trying to rename 6th Avenue “Avenue of the Americas” and finally relented in the 80s, posting 6th Avenue signs in addition to AoftheA, and a tradition was begun.

After 9/11/01, thousands of streets were ‘renamed’ for local heroes who died on that date, but the signs were merely added above or below the existing street names. In this case, Harrison Street lives on in one or two chiseled signs on buildings.

Quirky storefronts along Columbia south of Kane include women’s underwear and unmentionables shop Winkworth and indie bookstore Freebird Books.

I’ve run this picture before but I enjoy it, since in October 2006 my first ForgottenBook signing was here and I attracted nearly 50 ForgottenFans who went with me on a short tour of the area afterward. It was a gratifying moment …

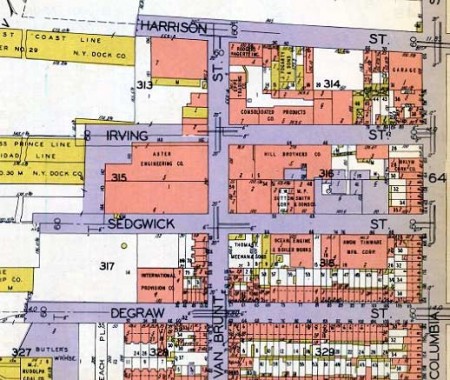

The east side of Columbia Street, the industrial side, presents quite a contrast to its quirkily commercial and residential side. Right: the lost streets of the Columbia Street waterfront, shown on this 1929 Belcher Hyde atlas. At the top is Harrison Street, now called Kane; and Irving and Sedgwick Streets, shaved to stubs west of Columbia Street in the 1960s and now gone completely. Van Brunt was truncated south of Degraw Street that same decade. Brick buildings are marked in pink. The city still has a Sedgwick Street sign, but there’s no street left. This area is on the drawing boards as a waterfront park.

Alma is a well-regarded Mexican restaurant at Columbia and Degraw Streets noted for its rooftop deck, open to the air in spring and summer. Degraw Street was closed to traffic between Hicks and Columbia for construction in March 2011.

MiKNic Lounge, 200 Columbia between Degraw and Sackett, is announced by a large wall mural. It has gotten consistent 5-star reviews on Yelp, in case you want to go in.

Sadly, Main Street Ephemera at Columbia and Sackett, “where the historical meets the hysterical” is no more, having lost its lease to an unmanageable rent increase. It sounded like the type of place I would have dropped in frequently:

Postcards, stereograms, trade magazines, burlesque programs, old menus, canceled checks, Esso maps, Tin Pan Alley sheet music, B-movie lobby cards, and publicity shots of forgotten crooners were [owner] Dave’s stock-in-trade. Word on Columbia Street

The poster is for 1958 sexploitation flick Unwed Mother:

The plot and title of Unwed Mother are virtually one and the same. Betty (Norma Moore), the heroine, falls for the smooth line of patter delivered by no-good heel Dona (Robert Vaughan). Pretending to be a man of wealth, Dona convinces country gal Betty to give him her paychecks, promising to pay her back as soon as his inheritance comes through. He also assures her that he’ll marry her when the time is right. When Betty becomes pregnant, she learns what the audience has known all along about the prevaricating Dona. After putting her child up for adoption, Betty has second thoughts, and thus spends the final reel chasing after the foster parents who’ve taken charge of her baby. Allmovie

Between Columbia and Hicks, both sides of sad Sackett are lined with early 21st Century lifeless-looking residential errata, created without a spark of imagination. But they do have modern washer-dryers and undoubtedly, the bathroom ceiling doesn’t drip, unlike chez webmaster, built in 1941.

On Sackett east of Columbia I spotted a Mercury Monterey in NY Yankees navy blue, a species I confess I had not encountered previously, though I had seen its cousin the Mercury Breezaway on Gatling Place a few months earlier. This one looks like it’s from the 1961-1964 series. It’s parked near the de rigueur live poultry market you find in out of the beaten track neighborhoods.

Van Brunt and Sackett Streets. When Van Brunt enters Red Hook it’s pretty much the main shopping and restaurant drag, but in Columbia Waterfront, it’s a mere conduit, mostly unmarked. Tour buses do use it as a quick way to the nearby cruise ship terminal.

Two peaked roof homes on Union, just east of Van Brunt. The one on the right has recently been renovated and a splash of yellow always perks up a block.

The Union Street Star Theater is the area’s prime performance space, though I can’t find a web link (send me one if you have it). The Red Hook Star-Revue, which I suppose also originates here, is a local paper.

Across the street are a group of buildings from the 1920s with decorative brickwork. I liked the window treatment on the bottom right.

ForgottenFan Raanan Geberer: The building, or at least the ground floor, is rented out by George Fiala, who has his direct-mail business, Select Mail, there (you can find his contact info on the Select Mail web site, although the site may still list the firm’s old Court Street address). As hobbies, George (a former newspaper guy) also publishes the monthly Red Hook newspaper, which he just started recently, and he also established the Star Theater in part of the space. There, he hosts little free gatherings where he invites people to hear local bands, as well as a weekly jam session. George himself is drummer with two of these bands, and I’m keyboard player with one of them. He’s a member of my alumni class at Bronx Science.

George Fiala: The story of the Star Theater is that it began as a stable and around 1892 was converted into an Italian Marionette theater. I found an interesting 1899 Brooklyn Eagle article about it in their archives. Afterwards it was mostly an auto-repair shop, and then, for a few years a place where marble countertops were cut. I rented it last year, a sloppy mess, and fixed it up. Not knowing about the theater, I built a stage for my band to practice, and was then delighted to find out it was the place’s second stage. I host a weekly music jam every Thursday from 8-11 pm – the musicians play for free and I give out beer for free – a good deal for me I must admit because the music has been sometimes pretty amazing. On other nights you’ll often find bands practice there – actually three bands that have formed out of the jams (in one of them I’m the drummer).

In 212 Columbia, in what appears to be a former bank building, the Brooklyn Collective has taken over since I was last here. Its website says:

Brooklyn Collective was established in response to the need for a space where craftsmen can showcase their work free from the pressures of mass-market retail. Through a cooperative effort, the collective seeks to push the boundaries of art and design, offering the public a unique view into what designers are capable of when they are given creative freedom.

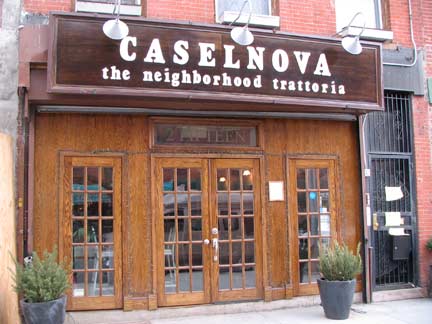

Across the street the Caselnova restaurant uses a typefont on the awning sign I haven’t seen in some time: Goudy Heavyface Condensed. They have the V backwards though.

Between Columbia and Hicks, Union Street is the main shopping drag of the Columbia waterfront district, at least for practical stuff, and the city has placed some type B Henry Bacon park lampposts on the sidewalks.

I was wondering about 131-133 Union, which appeared to have some importance in decades past. Brooks of Sheffield at Lost City has come up with the answer:

This is the most imposing building on the block between Hicks and Columbia (note the double address), and one quick glance at it will tell any free-lance historian that it was once a bank. Note the faux marble pillars, the vaguely classical architecture, the high doorway, the fake balconies. Of course, in the isolated Italian ghetto that this neighborhood once once, it wasn’t a bank the way you and I think of them. It was a private banking house, owned and run by one Antonio Sessa and his son Joseph…

The Sessas were obviously major community leaders. I was once told a story by a local that, during the Depression, the bank was the subject of a run, but that Sessa, George Bailey style, talked all those who had money in the bank out of withdrawing their funds. The Sessas were also arts supporters. They invited Guglielmo Ricciardi, the founder of the first Italian-American theatre troupe in Brooklyn, into the back of his bank, where he and various amateurs thespians would rehearse various comedies. Sessa provided financial support. And a bank clerk named Francesco De Maio helped the company rent the Brooklyn Athenaeum, which used to stand at the corner of Atlantic and Clinton, and was a cultural beacon for the area.

Banco Sessa was absorbed by Bancitaly in 1927. Joseph Sessa still ran the bank, though. Then in 1928 Commercial Exchange Safe Deposit Company bought it. The address was First National City Bank by the 1950s, with Sessa still there. At some point it became Citibank, which eventually decamped to its present location on Court Street near 1st Street.

I was attracted to 135 Union because of its pale green paint job, and its midwife shingle. You don’t see one of those every day.

This hand lettered sign (by Jay Crider) is a masterful representation of its craft, and I’m glad the folks at Brooklyn General (which mainly sells yarn, fabric and sewing materials), decided to maintain it from a former incarnation that closed in 2006.

A couple of doors down is the Famous House of Pizza & Calzone; not sure how long it’s been here, but it looked completely remodeled within, with lots of wood paneling and flat screen TV’s. The slice is good, but I’m hardly a gourmet and I think most slices are good.

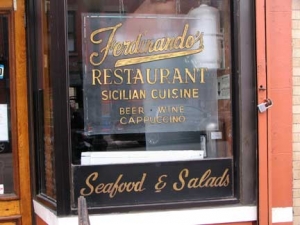

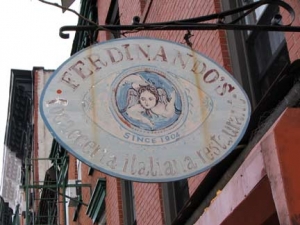

Ferdinando’s at Union just off Hicks is a testimony to Carroll Gardens’ and the Columbia waterfront’s Italian heritage. Ad the sign says it has been in business since 1904. Sicilian specialties are the forte, especially the flat bread panelle.

The storefront’s venerable glass painted lettering is still there and the now-fading handpainted sign, with an unusual triskelion cherub.

ForgottenFan Robert Oppedisano: the panelle at Ferdinando’s are chick pea flour croquettes, fried, sometimes served in a Sicilian seeded bun with shaved provolone and ricotta (great). The name refers to the croquettes, not the sandwich.

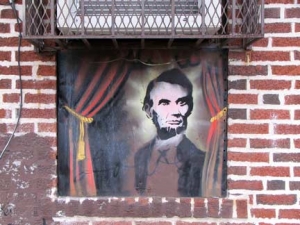

144 Union on the corner of Hicks had been occupied by the Petite Crevette, a French seafood restaurant, with a mural by artist Jay Crider on the Hicks Street side, with Lincoln peeking from a side window. The name means “little shrimp.”

An awning and painted ad on either side of Hicks, featuring red, white and green from the Italian flag. Latticini Barese, at 138 Union, closed in 2002 after a 75-year run.

Old man Joe Balzano, when he was still up and active, rose early every morning to hand make the store’s mozzerella in the back room of the store. It was the best cheese of its kinds in the area. Once, my visiting mother had the chutzpah to ask if she could watch him do his magic, and he agreed. I didn’t join her, being too embarrassed by her brazenness, and I have regretted it ever since. I would have loved to have seen Joe at work.

The place also had a memorable sausage salad and a peerless sandwich called “The Fireman’s Special,” which included every spicy cured meat and hot pepper you can think of.

Things came to an end when Joe was hit by heart trouble and retired. Lost City

Moving on to President Street, perhaps the most interesting development is at 102 (between Hicks and Columbia) where the former Margaret Palca bakery has been reinvigorated as Elegantly Iced, a custom wedding cake shop. The old sign I photographed in 2008 has stayed in service though.

President, Carroll and Summit Streets between Columbia and Van Brunt Streets feature the 1983 Columbia Terrace development, which looks fairly prefab but does have that increasingly rare NYC feature…green lawns. In the 1970s, most buildings here had to be razed so NYC could complete a sewer renewal program. The city contracted the Kings Monadnock Construction Company to build multifamily homes to replace what was lost.

The venerable Sokol Furniture Company on Columbia betwen President and Carroll have been here a long time, likely since the 1940s.

Columbia Street has had a distinctive set of davit-style lampposts, unusual for NYC, since the mid-2000s. Davit posts, in which the shaft curves out and holds the luminaire, are unusual in NYC; the only other set is on the reconstructed Houston Street.

The crossbar on the post indicates that the city will be placing stoplights here before too long.

Season’s greetings, and a suggestion, in March 2011 on Columbia and Carroll Streets.

Along Carroll between Columbia and Van Brunt. Like I said earlier, a little yellow really spiffs up a place. 33 Carroll reminds me of those cheezy 1980s TV movies in which a place is a factory by day but at night the forklifts are moved out and the spandex and headband crowd move in to a converted club/gym. Left: a musician friend of mine used to live at 15 Carroll, the building in the left. It was impeccably maintained inside.

Right: Van Brunt at Carroll.

The pedestrian bridge at Summit Street was built when the BQE was, in the early 1950s, and at that time, there was still some leeway for a little embellishment. The bridge has an arched grace about it, and the distinctive bridge posts that look like bishops’ staffs, appropriate with the venerable St. Stephens Church the backdrop.

The buildings on the south side of Summit, west of Hicks, have these marvelous wrought iron shelters at the front doors. If you’re fumbling for the keys you don’t have to get wet while doing so. 114 has some stained glass on the transom.

OK, name that car in an abandoned car lot at Columbia and Summit (see below for some more interesting abandonments. Columbia Street is not immune to depressing modernism, like these towers that are echoic of the Tredway White houses on Hicks and Warren, but is a letdown in every other way.

The derelict car you asked about is a Mercedes-Benz SL, 1972-89. –ForgottenFan Mark Nahmias

Early in the 20th Century, old pictures show Hamilton Avenue as a bustling route with stores, apartment buildings, trolley tracks, and a ferry to Manhattan at the northern end. Since the construction of theBrooklyn Battery Tunnel began in 1940 (it was suspended for the war, with the tunnel finally opening in 1951) Hamilton Avenue was eviscerated and it now serves as a service road under and surrounding the Gowanus Expressway, which fulls into the tunnel and the BQE. In 1929 Robert Moses announced that he wanted a crossing to connect Hamilton Avenue and Battery Park, originally to be a tunnel, but he then desired a bridge. He was handed one of his few defeats on a road project until the 1960s. The tunnel was built instead. Right: any takers?

A flock of abandoned Airstream trailers in a lot at Woodhull and Columbia Streets. How did they get there?

At 29 Woodhull east of Columbia, the house is much altered from its early days, but the date of construction can still be seen at the cornice. Across the street this 1909 building has been renovated into total blandness.

St. Stephens/Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary Church on Summit Street barely escaped the Hand of Moses when the BQE was put through. Its magnificent spire has held firm through thunderstorms, blizzards and tornadoes. The church was constructed from 1873-75 with famed ecclesiastical architect Patrick Keely wielding the slide rule. It was devastated by a fire in 1951 and rebuilt largely identically in 1952.

Two buildings, Woodhull and Hicks Streets, March 2011. Will the passage of time give the building on the left an aura of sophistication? It looks knocked-off, hastily built and cheap at present but will age be kind to it?

Finishing at the Clement Garage, Rapelye and Hicks. Rapelye has been covered before in FNY, but Cobble Hillers, give me the correct pronunciation: RAPP-el-ie, RAPP-el-ye, or ra-PEL-ye? I have to know.

Photographed March 12, 2011; page completed March 19

Your webmaster Kevin Walsh: kevin@forgotten-ny.com

©2011 FNY