Beach Street ranks among the Forgotten men among its neighbors in Tribeca. Two blocks between West and Greenwich were hacked off in favor of the Independence Plaza apartment house development in the early 1970s (depriving present-day New Yorkers, perhaps, of a monument commemorating the landing of the very first steam locomotive in America, the Stourbridge Lion, at the Hudson River and Beach Street in 1829; the train was able to reach the then-unheard of human-powered speed of 10 MPH). Earlier than that, the section of Beach between Hudson and Varick was renamed Ericsson Place (none of my sources acknowledge when, but I have map from the 1930s with the Ericsson name already appended).

While Beach Street is not named for any nearby seaside recreational area but for Paul Bache, son-in-law of Anthony Lispenard, who owned much of the property in the area in the early 1800s, Ericsson Place was named for naval industrialist and inventor John Ericsson (1803-1888).

John Ericsson was one of the naval industry’s greatest innovators. Among his designs:

— the screw propeller

— the first armored warship, the U.S.S. Monitor

— the rotating gun turret, first used on the Monitor

Born in Sweden, Ericsson lived in New York City from 1841 until his death. The U.S.S. Monitor was built and launched in Greenpoint, Brooklyn.

Beach Street took Ericsson’s name because he lived here, in a building at 36 Beach Street, which, as Ericsson Place, now faces the off ramps of the Holland Tunnel but was then St. John’s Park, one of the city’s premier residential and recreational squares of the mid-19th Century. He purchased a 3-story brick house at 36 Beach, lived there till his death in 1888, and the house was razed in 1920. The story of Ericsson’s house doesn’t end there, however. For decades after its demolition, the ghost outline of John Ericsson’s house could be seen on the street named for him (photo above right). The ForgottenCamera captured it a few months before a tall development obscured it from view.

Beach Street resumes its name for a couple of blocks west of Hudson Street, and walking west I noticed the new iron lampposts that illuminate the exit ramps of the Holland Tunnel (which, except for the Bell luminaires, don’t jive with any former genus or species of classic NYC lamppost). I then spied the handsome loft building on the SW corner of Hudson and Beach, which on the ground floor is home to Grand Rapids, MI -based upscale home furnisher Baker.

I noticed the name of the furnisher is set in classic Garamond, named for French printer Claude Garamond, and one of my favorites:

He established the first type foundry — a business set up specifically to market “type faces” to printers. Through this enterprize, he is also attributed for being the first to develop italic Romanesque type faces, and then to establish the relationships between the postures of the type into type family relationships. His classic Old Style type face “Garamond” is considered one of the best in all typographic history. [Graphic Design]

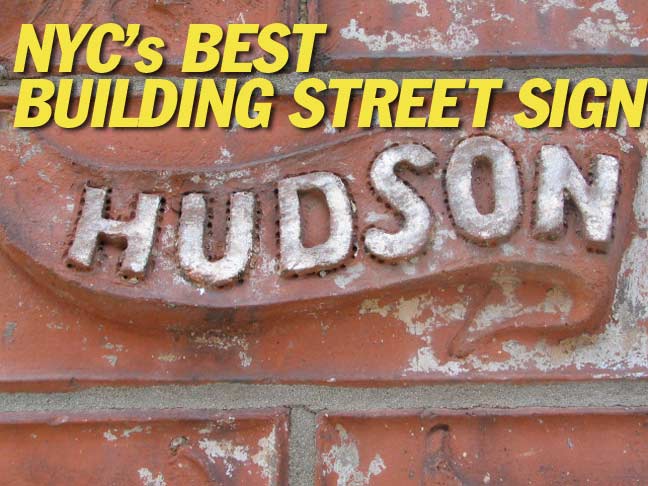

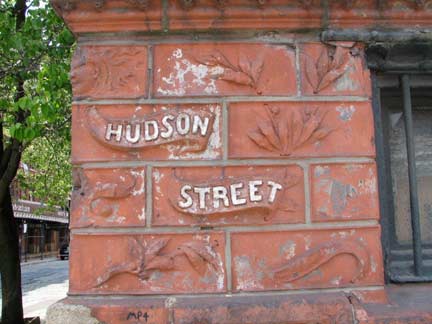

The star of the show, though, for Forgotten purposes, is on the northwest corner of Hudson and Beach, at 135 Hudson. The AIA Guide to Manhattan says it was constructed in 1886 by Kimball and Inhen (I know nothing about the company, but could the Kimball have been Francis H. Kimball, the creator of some of NYC’s greatest buildings…the Corbin Building on Broadway and John Street, the Montauk Club on 8th Avenue and Lincoln Place in Park Slope, and Edgehill Church in Spuyten Duyvil?

…where the builders left

no doubt about the address, placing the two cross streets in brownstone tablets in carved banners. In the 1800s, street signs, as attachments to utility poles, were in their infancy and the most common method was for the owners to chisel the street names the building faced on the facade, or to attach a metal sign bearing the name or names to the side of the building. On 135 Hudson, Kimball and Inhen employed uncommon craftsmanship to street identification.A corner goddess beckons us in. The building is now mainly used as artist lofts, but expensive apartments have begun to replace them; here’s a look inside one that was for sale in the spring of 2008.