PART 2: QUEENS

I’m surprised I never thought of this until now, after about fifteen years of doing Forgotten New York. I’ve seen these historic plaques mounted on poles as I travel in Nassau and Suffolk Counties, and a very occasional one in the five boroughs. They’re part of an initiative devised by New York State Education Department in 1928 to mark places of historical significance, and for nearly forty years, almost 2800 such markers were placed all over the State.

The signs themselves are marvels of design, in my opinion. Most of them feature dark blue backgrounds with gold raised block lettering and trim, though there are variations in color and lettering, and very occasionally, shape, just to change it up, I imagine. The State discontinued the series in 1966 after high speed travel on expressways became the norm.

This flickr page that assembles photos of the State markers taken by various photographers illustrates the basic, simple and readable design of these signs.

No study had yet been made of the 92 locations within the five boroughs that these signs delineated, so I decided to do one myself with photographs culled from my own collection; I also used scans from books I had in my collection, and screen captures from Google Street View.

It should be noted that this page doesn’t include the brown and gold markers placed by the Richmond Hill Historical Society and the blue and gold ones placed by the Woodhaven Cultural and Historical Society, which closely resemble the New York State signs. I gave those signs their own page a few years ago, though I didn’t catch them all.

Of the 92 NYS historical signs placed around town beginning in 1928, only a mere handful are still there. Over the decades, the local youth have removed or vandalized them, some have been claimed by new construction or car crashes. Some of the remaining ones are in very poor shape, while others have been restored to better-than-ever construction….

In each case I’ll give the location as shown on the NYS Museum site, as well as the text as originally rendered on the sign, per the Museum listing.

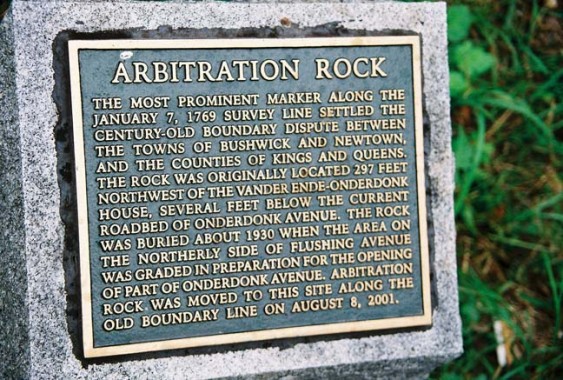

Arbitration Rock

The NYS historical marker for this supposed ancient divider between Kings and Queens Counties was originally plaxed on Flushing Avenue near Onderdonk. The sign text stated:

Arbitration Rock is under this point. It marks the settlement, in 1769, of a boundary line dispute between the Towns of Newton and Bushwick.

The Van Der Ende-Onderdonk House, also known as the Van Nanda-Onderdonk House, the last in a group of colonial-era Dutch houses in the Ridgewood-Maspeth area, was built around 1710. It was most likely built by a farmer, Paulus Van Der Ende of Flatbush; his son or grandson, Frederick Van Nanda, owned it in the late 1700s and early 1800s. It was sold to Adrian Onderdonck in 1831 and the Onderdon(c)ks and their family lived in the house until the late 1880s. Of course, the adjacent street, Onderdonk Avenue, is named for the family.

The house is just over the Queens side of the borough line. In the back yard of the Onderdonk House you will find the famed “Arbitration Rock” that, according to some accounts, denoted a disputed Brooklyn-Queens boundary. It was located to the west of Flushing Avenue and Onderdonk Avenue until Onderdonk was extended west in the 1930s. Arbitration Rock was buried beneath the pavement for decades, until a chance excavation in December 1999 revealed it once more. Surveyor Peter Marschalk set the boundary, originally the Kings County-Newtown Township line, in 1769.

But… is this really Arbitration Rock?

Bob Singleton, director of the Greater Astoria Historical Society, with which FNY is affiliated, disagrees, favoring this large rock found on Varick Avenue near Randolph Street a few blocks away:

The confusion has to do with which right branch of the stream you use – the main waterway, or English Kills (so called because of the claim by the English in Maspeth against the Dutch in Bushwick) Both the Dutch and English continously harassed them to leave, finally folding the village up into Newtown (1705) and giving the salt meadows to Bushwick (1769). My grandmother’s family (as many others) left in a migration to Princeton about 1705 for this reason.

Of note was the Arbitration Rock Festival, which took place at the Onderdonk House in August 2012, a party with beer, games, eats and several local bands playing in the spacious backyard. It is hoped it could become an annual event.

Cadwallader Colden House

photo: New-York Historical Society

The estate of Loyalist New York State Lieutenant Governor Cadwallader Colden (1689-1776) was located on what is now near the main entrance of Mount Hebron Cemetery on the south service road of the Horace Harding Expressway where it meets the Van Wyck Expressway.

Colden, a politician, botanist, merchant, physician and historian, wrote several historical treatises and was a friend of Carolus Linnaeus and Benjamin Franklin, but he remained loyal to England, enforcing the Stamp Act and unveiling a statue of George III in Bowling Green; enraged patriots burned him in effigy. He retired from politics and died at his estate, called Spring Hill, here in southern Flushing in 1776. Colden’s grandson Cadwallader D. Colden was NYC mayor from 1818-1821 and a NYS Congressman from 1821-1823; he is buried in Uptown Trinity Cemetery. The senior Colden is remembered by a Flushing playground and by Colden Street.

Spring Hill, the Colden estate, was sold to the Durkee family during the 19th Century and was acquired by Cedar Grove Cemetery in 1893. Cedar Grove contained the old Willett family burial grounds, where the senior Colden was believed to have been laid to rest. Colden’s mansion, seen above, became the cemetery’s administrative building before it burned down in 1930. Meanwhile, in 1909, Mount Hebron Cemetery was established for the Jewish commuinity and has since acquired much of the old Cedar Grove Cemetery property. The Willett burial grounds are still there, marked by some very old headstones, near the Mount Hebron entrance on the Horace Harding Expressway.

1909 map of the Colden/Spring Hill mansion, whose rough location is marked with an X. Strong’s Causeway was eliminated by the construction of Nassau Boulevard, soon to be named Horace Harding Boulevard, in the 1930s. Ireland Mill Road is now College Point Boulevard. Note that the Flushing River still flowed south here in 1909.

Again, I have marked with an X the approximate location of the Cadwallader house. The NYS historical marker for the Cadwallader Colden House is given to be at “Horace Harding Blvd., East of Rodman St.” and read:

Built 1762. Stood opposite. He was Lieutenant Governor of the Province of New York 1760 to 1775. He died here on September 28, 1776.

Since this Hagstrom map of the area was made in 1949, there have been a lot of street renamings and changes. Beginning in the 1920s, Nassau Boulevard was built between Queens Boulevard and Manhasset as a surface four lane boulevard, and was actually built to allow traffic to easily access the Shelter Rock Country Club. A frequenter of the club was banker and president of the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad and of the Bronx Gas and Electric Company Horace Harding, for whom Nassau Boulevard was renamed in 1929. In the Fab Fifties, Robert Moses pushed through the Long Island Expressway, replacing the boulevard, which retains the Harding name on the service roads. A small piece of Nassau Boulevard diverging from the expressway in Little Neck retains the old name.

Meanwhile, a small piece of what had been called Ireland Mill Road was renamed Rodman Street in the early 1900s. Rodman Street ran into Lawrence Street, which was a major north-south route that became the College Point Causeway, a formerly cobblestoned route across the marshes between Flushing and College Point. In 1969 the decision was made to group 122nd Street in College Point, College Point Causeway, most of Lawrence Street, and Rodman Street under one name: College Point Boulevard; small pieces of Lawrence Street (which itself is named for a prominent Queens family) are still there, north and south of the LIE.

Lastly, the “North” on the 1949 map is the North Hempstead Turnpike, a very old road that connected to Corona via Strong’s Causeway; on the east, it led to roads that went to Hempstead in today’s Nassau County. In 1957, it became Booth Memorial Avenue, after Booth Memorial Hospital, named for the founder of the Salvation Army, was built. Today, BMH is now New York Hospital, so the street commemorates only William Booth.

DeWitt Clinton House

Maspeth isn’t a location many associate with DeWitt Clinton (1769-1828), a founding father who served as NY State Assemblyman, NYS Senator, NYS Governor, US Senator and NYC Mayor during an illustrious career capped by his indefatigable support for the Erie Canal. Several streets around town were named for him, and when Green-Wood Cemetery opened in 1838 his remains were later exhumed from the original burial plot in Albany, NY and moved to Brooklyn.

DeWitt Clinton lived in Maspeth for several decades in this house that had stood near Newtown Creek. The house was built in the mid-1700s, while Clinton moved here about 1780; it is said original plans for the Erie Canal were drawn up here. During the Revolutionary War the house was occupied by General Warren, and Gen. William Howe planned an invasion of NYC via Newtown Creek here.

The house didn’t fare well in its later years, as the area surrounding it became increasingly industrial, and it was divided into tenements in the 1920s and burned down in 1933.

The NYS historical marker for the Clinton House stood on 58th Street and 56th Road and read:

DeWitt Clinton House 1790-1828. Stood several hundred feet north of here. Gov. Dewitt Clinton worked on plans for Erie Canal here.

First House Number in Queens

At Park Lane South and 85th Street in Woodhaven we find a rare well-preserved NYS historic sign, standing on private property.

The sign marks the first address in Queens to be renumbered under the “Philadelphia plan” which renumbered most of Queens’ streets, with lower numbers at the East River and proceeding east and south.

Many years ago, when Queens was a collection of small towns divided by acres of farms and fields, every town and city had its own street naming and numbering system. This was all right when Queens (then also comprising what is now Nassau County) was a separate and self-governing county. Once Queens consolidated with New York City and subsequently became slowly urbanized, this was a situation that could not be allowed to stand as a plethora of Washington Streets, Main Streets, and 1st and 2nd Streets found themselves in the same street directory in the city ledgers.

And so, the Queens Topographical Bureau, under the guidance of C. U. Powell, was set the task of unifying Queens’ street system in the 1910s. To do this just about every street in Queens was assigned a number, except those in historic areas such as Flushing; some existing major roads kept their names, but were assigned the honorific Boulevard or Parkway to replace what was a mere Avenue or Road; the Jackson Avenue – Broadway combination was renamed Northern Boulevard, for example, while Little Neck Road became Little Neck Parkway. Numbered Avenues, Roads, Drives and Courts run east-west, while Streets, Places, Lanes and Terraces run north-south. Streets run from 1 to 271, and Avenues from 2 to 165: why Queens does not have a 1st Avenue is a mystery.

See this Brooklyn Daily Star article, headlined “Street Names Still Bothering,” about the proposed changes in Flushing, which successfully resisted the numbering.

The system works well, albeit with the loss of personality and individualism that named streets personify. However, in neighborhoods where the numbers are all the same, things get confusing. In western Maspeth, 56th Street meets 56th Drive, which also meets 56th Terrace; 57th Road meets 57th Place; 58th Street and 58th Place meet 58th Avenue and 58th Road; 59th Street meets 59th Road and 59th Drive; 59th Place meets 59th Drive; 60th Street meets 60th Avenue, 60th Road and 60th Drive; 60th Place meets 60th Avenue and 60th Court; and 60th Lane meets 60th Avenue, 60th Road and 60th Drive. And of course the 57s meet the 58s, the 58s meet the 59s, the 59s meet the 60s … and on and on…

The handsome marker above is one of a couple of dozen in Woodhaven and Richmond Hill. However, the other signs are fairly new and were placed by Woodhaven and Richmond Hill historical societies.

Foster House

This NYS historical marker has me a bit stumped, though I know of the general area, on Douglaston Parkway east of Alley Pond Park, somewhere between Northrn Boulevard and the Long Island Expressway:

Foster House stood opposite. Stone part used during Indian attacks. Thomas Foster was hanged by Hessians; his son rescued him.

From the Alley Pond Park wikipedia entry:

What is now Alley Pond Park was once home to the Matinecock, who harvested shellfish from Little Neck Bay. The English began to colonize the area by the 1630s, when Charles I granted Thomas Foster 600 acres (240 ha), on which he built a stone cottage near what is now Northern Boulevard. Mills were built on Alley Creek by Englishmen Thomas Hicks and James Hedges, while other colonists used the valley as a route to Brooklyn, theHempstead Plains and the Manhattan ferries. George Washington (1732–1799) is thought to have used this route for his 1790 tour of Long Island. The valley’s usage as a passage, or perhaps its shape, may ultimately account for its name; in any case, an 18th century commercial and manufacturing center there became known as “the Alley.”

There’s nothing about the Hessians, who were aligned with the British during the Revolutionary War. Perhaps the sign refers to a descendant of the first Thomas Foster. In any case, the hanging would have been unsuccessful, since he was ‘rescued.’

No trace remains of the stone house or the historical marker.

Francis Lewis

The marker delineating the estate of Francis Lewis, the signer of the Declaration of Independence from Queens County, stood at 7th Avenue where it meets Clintonville Street and 151st Street in Whitestone.

Lewis (1713-1802) was a Welsh merchant who emigrated to Whitestone, then part of Flushing, in 1734. In the 1750s he entered politics, serving as a member of the New York Provincial Congress, and was later elected as a delegate to the NY Continental Congress in 1775. His mansion was destroyed by the British the following year, aware he supported the patriots’ cause.

In the 1930s, when Cross Island Parkway was under construction, an already-extant road named Cross Island Boulevard renamed Francis Lewis Boulevard. The road was extended south of Jamaica by renaming a number of previously-existing roads.

Morgan Lewis (1754-1844), son of Francis, served in the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812; in between, he was NYDS Attorney General, a State Supreme Court justice, and NYS Governor. Lewis Avenue in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn and Lewis Street in Manhattan’s Lower East Side are named for Morgan Lewis.

Shown in the above photo is Queens judge Charles Colden, a descendant of Cadwallader Colden (see above), who helped establish Queens College in the 1930s. Concert auditorium Colden Center is named for him. photo from Old Queens, NY in Early Photographs, Seyfried and Asedorian

General Howe Headquarters, Elmhurst

This NYS historical marker stood at the southwest corner of Queens Boulevard and read:

Gen. Howe’s Headquarters stands opposite here. Howe wrote his report of the Battle of Long Island here Sept. 3, 1776. Was Renne home.

According to the WPA Guide to New York City, originally published in 1939, this house, built by Samuel Renne, was a “three-story frame dwelling with a high basement, porch and three sharp dormers.”

On a ForgottenTour in April 2010, I am bullhorning where the sign once was, at Queens Blvd. and 57th Avenue. The recently renovated (as a church) Elmwood Theatre, built in 1928, stands across the street.

Jackson’s Mill

The NYS historical sign, which I’d guess was about where 94th Street is bridged over the Grand Central Parkway at the entrance to LaGuardia Airport (the location given is “this mill stood about at the crossing of Grand Central Parkway”) said:

Here stood Wessel’s Grist Mill, 1640. Razed in early Indian War, later mills of Luyster, Kip, Fish and Jackson used the same site.

In Old Queens NY in Early Photographs: The old mill … powered by a large undershot wheel, used to grind wheat and corn for the inhabitants of north Queens until about 1870.

The mill was first built by a Dutch settler, Warner Wessels, in the mid-1650s in what was once Trains Meadow but is now Jackson Heights. Its last owner was Samuel Jackson; Jackson Heights today bears his name.

A reminder of the mill is today’s Jackson Mill Road, which runs in two pieces in Jackson Heights. It was originally called Old Bowery Bay Road and has survived because it was used as a trolley route well after Jackson Heights was developed around it.

Moore Homestead

A NYS historic marker at Broadway and 45th Avenue, now the Moore Homestead Playground, read thusly:

Moore Homestead, 1662. Ancestral home of Dr. C.C. Moore, author of “Twas the Night Before Christmas“. Later the home of grandson Commodore O.H. Perry.

The long history of this site features colonial settlers, a tasty apple, a beloved children’s poem, subway construction, and a neighborhood playground. In the mid-1600s Captain Samuel Moore was granted eighty acres of land in the area to recognize the efforts of his father, Reverend John Moore (1620-1657), in arranging the purchase of Newtown from local Native Americans. Captain Moore built a house here in 1661, and the property was handed down from generation to generation of his descendants. During the Revolutionary War, the British General William Howe made his Long Island headquarters at the homestead. The site is also known as the birthplace of the famous “Newtown Pippin” apple.

Clement Clarke Moore (1779-1863) was the great-great-great grandson of Reverend Moore. Born in New York City, Clement spent much of his boyhood and youth at the family estate in Newtown. He was tutored at home by his father and graduated from Columbia College with a B.A. in 1798, an M.A. in 1801, and an honorary LL.D. in 1829. Moore served as a professor of Oriental and Greek literature at the General Theological Seminary in Manhattan from 1823 until he retired in 1850. Fluent in six languages, he published numerous scholarly works, including a Hebrew lexicon, a biography, and several treatises and addresses. NYC Parks

In the Dirty Thirties, NYC was relentless about bulldozing or otherwise destroying historic properties before preservation laws were on the books, and the Moore homestead didn’t survive the construction of the new IND subway under Broadway in 1933. The land where the house had ben became a playground in 1954 and was renamed for the homestead in 1987.

Meanwhile, two Moore burying grounds survive: a hidden one in a playground at 90th Street and 56th Avenue, and the Moore-Jackson Cemetery on 54th Street between 31st and 32nd Avenues in Woodside.

General Nathaniel Woodhull

St. Gabriel’s Church, Jamaica Avenue and 196th Street

A NYS historical marker stood on Jamaica Avenue across the street from St. Gabriel’s, which read:

Gen. Nathaniel Woodhull was captured and fatally wounded by the British in Increase Carpenter’s House 200 feet north of this spot.

General Nathaniel Woodhull (1722-1776) was a leader of the New York Provincial Congressand a brigadier-general of the New York Militia during the American Revolution. He was born on December 30, 1722 in Mastic, Long Island, Province of New York, the son of Nathaniel Woodhull and Sarah Smith. His family had been prominent in New York affairs since the mid seventeenth century.

In October 1775 he was made brigadier general of the Suffolk and Queen’s County militia. In 1776 took part in the Battle of Long Island. Leading up to the battle, his militia began removing livestock and matériel to prevent its use by the British. The Battle of Long Island resulted in his being cut off and he retired to Jamaica. Relief was not forthcoming, and his situation deteriorated.

Woodhull was captured near Jamaica by a detachment of Fraser’s Highlanders led by captain Sir James Baird. He was struck with a sword multiple times, injuring his arm and head by a British officer purportedly for not saying, “God save the King,” as ordered, saying instead “God save us all.” He was taken to a cattle transport, serving as a prison ship in Gravesend Bay. A sympathetic British officer had him transferred to the century old house built by Nicasius di Sille in the Dutch village of New Utrecht which is now a part of Brooklyn. The house was demolished in 1850 by the owner Baret Wyckoff. It was located in the current vicinity of 84st. and New Utrecht Ave. His arm was amputated in an effort to save his life, he managed to call for his wife who was at his side when he died on September 20, 1776. He was buried at his family home. condensed from wikipedia entry

Both Woodhull and Carpenter are remembered by street names in this section of Holliswood on the eastern end of Jamaica.

Prince Homestead

The Prince family opened the first commercial plant nursery in the USA in 1735, specializing in fruit trees. Patriarch Robert Prince learned horticulture from the remaining Huguenots (French Protestants) in the Flushing area, and the business flourished during and after the Revolutionary period. In the early 1800s, Robert’s son William opened the first bridge over the Flushing River that allowed wagon and cart traffic to enter from western Queens. Competing plant nurseries of the Bloodgood and Parsons families also opened, and in the 1800s, Flushing was known around the Northeast for horticulture. Eventually, though, as Flushing gradually became more urban, the nurseries moved out or failed. Today, the only reminder of the plant shops is Flushing’ street plan, which bears plant names from A (Ash) to R (Rose), and Prince Street.

The Prince family home was constructed at Broadway and Lawrence Street (today Northern and College Point Boulevards) by the Embree family around 1750, and purchased by the Princes in 1800. It was torn down in the 1930s as the area became industrial.

The NYS historic maker here said:

Prince Homestead stands opposite. Built by E. Embree 1780. Washington stopped here to see the Prince Nurseries during his trip to Long Island 1789.

When Washington visited the Prince nursery he was unimpressed, but when Thomas Jefferson visited the following year he made several purchases that were planted at Monticello in Virginia.

Prospect Cemetery

Prospect Cemetery is an old FNY favorite, and claims one of Queens’ four surviving NYS historical markers, on 159th Street between Archer and Liberty Avenues.. In poor shape just a few years ago, it has been spiffed up and resurfaced as part of the overall campaign to restore the formerly forlorn burial ground. The Chapel of the Sisters (above) has been fully restored as a concert space.

The Cemetery has been part of two ForgottenTours and was featured on one of FNY’s first features in 1999. Prospect Cemetery Association president Cate Ludlam, whose ancestors are buried here, partially credits FNY with getting the word out about this 350-year old piece of Queens history.

FNY Tour #51 in Prospect Cemetery and King Manor

Quaker Meetinghouse

This surviving Queens NYS historical marker is found at the 1694 Flushing Quaker Meetinghouse at Northern Boulevard and Linden Place. It’s definitely in need of the same treatment the Prospect Cemetery marker got. Oddly, the John Bowne House around the corner, which was built in 1662, didn’t rate a marker. Here, one of the new series of Flushing historic markers has been installed, making this one rather superfluous.

The Friends Meetinghouse has been used for Quaker religious services since it was constructed, a span of over 300 years. Not only is the building remarkable for its great age … it also figured in one of the first shots fired in the ongoing war for religious and personal freedom that is being fought even today.

In 1657, the Dutch still were in charge of New Netherland, and Governor Peter Stuyvesant ruled with an intolerant hand. He forbade any religion but the Dutch Reformed Church of his homeland, even for English settlers who were starting to trickle in. Quaker settlers sent a letter to Stuyvesant in that year that has come to be known as the Flushing Remonstrance, that reiterated the settlers’ desire for religious freedom. The document was signed by Flushing’s town clerk and sheriff, who were not Quakers. Nonetheless, they were soon tossed into prison, then summarily fired. 37 years after the Flushing Remonstrance was presented to Stuyvesant, this meetinghouse was raised in 1694. At the rear you’ll find a quiet churchyard with graves hundreds of years old that makes quite a rural riposte to bustling Northern Boulevard. More old stones can be found at St. George Church at Main Street and 37th Avenue; that church, where Francis Lewis of Declaration-signing and Queens boulevard fame was a vestryman, dates to 1854.

ForgottenFans gained entry to the Meetinghouse on FNY Tour #21 in 2005.

Rapelye’s Mill

Shown here is the intersection of the Horace Harding Expressway and Colonial Avenue, formerly one of NYC’s many Old Mill Roads. A NYS historical sign that once stood here said:

On this site, 1655, Captain John Coe erected the first grist mill in Newtown, used as a mill by Rapelye until 1875.

The first European development on Horse Brook, a former stream that ran from the Flushing River into mid-Elmhurst, began in 1652, when Captain John Coe built a mill on Horse Brook roughly where Colonial Avenue meets the Long Island Expressway. The mill was built on a small island in the stream. His father Robert was a founder of Hempstead and also bought Jamaica from the Jameco Indians. In 1655, the residents of Maspeth and Newtown (later renamed Elmhurst) paid for a road to the mill, which supplied their villages with grain and corn. Nine years later, the Dutch-controlled territory passed into English hands.

Coe’s Mill appears on the left, and the Coe’s Mill (William Geyer) Hotel appears on the right in this early 20th century view. The streambed is now covered by the Long Island Expressway. This photo is from “Story of Corona” by Vincent Seyfried. Sergey Kadinsky, from FNY’s Horse Brook page

Remsen Cemetery

Yet another surviving NYS historical marker is at the tiny Remsen Cemetery at Yellowstone and Woodhaven Boulevards. It’s one of a handful of such surviving family burial plots scattered around the borough; among them are two belonging to the Lawrence family in Astoria and Bayside. Even more have been buried beneath architecture and parkland; some, like the Wyckoff-Snediker Cemetery in Woodhaven, are on church property and are not visible from the street.

Remsen Cemetery contains eight burials from 1790-1818. A historical plaque identifies Colonel Jeromus Remsen (1735-1790), who served in one of the major Revolutionary War chapters, the Battle of Long Island.

The Hempstead Swamp once occupied a vast area of land that sits just east of present-day St. John’s Cemetery in Queens. The greater area was first settled in 1653 as ‘Whitepot’ by English and Dutch farmers, including the Remsen, Furman, Springsteen and Morrell families. They found the land good for growing hay, straw, rye, corn, oats and various vegetables. During colonial times, there were only a few roads that cut through the marsh. One of these was Whitepot Road, known as Yellowstone Boulevard today.

The other was Remsen’s Lane, a road which became 63rd Drive and 64th Road. The Remsen family lived along the road, and their burial ground, which includes the resting place of Revolutionary War veteran Colonel Jacobus Remsen, is still intact here.

Near the cemetery stood a school called the Whitepot School, built by the founding families, which served the area into the early 19th century. Christina Wilkinson, from FNY’s Rego Park page

St. George’s Church

St. George’s Episcopal Church of Flushing. Main Street and 39th Avenue, formerly boasted a NYS historical marker:

Second Episcopal church on Long Island; Founded 1702; Chartered 1761 by King George III; first church 1746.

The present church is the third on the site, constructed from 1853-1854.

The third and present church occupies the same site as the original building and was built from 1853-54. It was designed by Frank Wills and Henry Dudley, architects associated with The New York Ecclesiological Society that had an interest in the development of Gothic Architecture as a new style (Neo-Gothic) for American churches. Local craftsmen were engaged and regional materials were used. The building includes walls of randomly laid granite rubble, fine stained glass windows. Above the entrance is a 150-foot tapered stone tower that houses a bell recast at Troy, N.Y., using the 1760 bell’s metal and bearing the inscription, “The gift of John Aspinwall, Gentleman, 1760.” American Guild of Organists

The tall steeple shown here was blown off by a tornado on 9/16/2010. There isn new construction at the church in 2013, so perhaps it can be replaced.

Stevens House

Above is a screen shot of 30th Road between Vernon Boulevard and 12th Street. Somewhere on the block, thee had been a NYS historical marker…

Major General Ebenezer Stevens Home east of here. Born 1752; took part in Boston Tea Party; major of artillery in the Revolutionary War.

Ebenezer Stevens (1751-1823) was a participant in what became known as the Boston Tea Party. A member of the Sons of Liberty, he began his career in Paddock’s Artillery Company along the likes of Paul Revere and Thomas Crafts. Together with other members of the company, and under the leadership of Jabez Hatch, he participated in the Boston Tea Party. His later recollections to his family debunked the myth that the participants had dressed up as Native Americans…

Although it is stated in several sources that Stevens was a major general in the United States Army, there is no official documentation to support this notion. He was, however, a major general in the New York state militia after the Revolution and moblized militiamen to defend New York City in case of British attack in September 1814. He lived as a merchant in New York City. wikipedia entry

Walter Bowne

This is 155th Street between 33rd and 35th Avenues in Flushing, where there had been a NYS historical marker denoting the home of Bowne family scion Walter Bowne:

Site of his residence. Mayor N.Y. City 1829-33. Great great grandson of John Bowne, one of the original patentees of Flushing.

Nearby Bowne Park is named for the former mayor:

This Flushing park is bounded by 29th and 32nd Avenues, and by 155th and 159th Streets. It is named in honor of Walter Bowne (1770-1846), who served as a State Senator and as New York City Mayor. Mr. Bowne’s summer residence stood on this property until March 1925, when fire destroyed the building.

As Mayor (1828-1832), Bowne is remembered for his strict policies aimed at preventing cholera epidemics. Following reports of an outbreak in a neighboring town during the summer of 1832, Bowne established a stringent quarantine policy regulating travel in and out of the metropolitan area. Bowne, like others of his time period, believed that cholera was spread through direct human contact. He required that all ships maintain a distance of at least 300 yards from municipal ports and that carriages remain at least 1.5 miles from the city limits. Bowne’s well-meaning attempts to prevent a cholera outbreak failed, and hundreds of New Yorkers died of the disease. It was not until 1883 that the German physician Robert Koch discovered that cholera spreads through contaminated water or food. By that time, cholera epidemics had been largely contained by the construction of the Croton Aqueduct and the provision of clean water for consumption and bathing. NYC Parks

As mentioned before, oddly enough, the 1662 Bowne House never got a NYS historical marker.

3/17/13