It has been 10 years since I walked the epically bleak Flushing Avenue from Maspeth to downtown Brooklyn with the Queen of Queens (Christina Wilkinson of the Newtown Historical Society). In January 2014 I decided to walk some of the route again, this time from Navy Street east to Broadway, from whence I would make my way northwest to the Willieburg and get the L back to Manhattan, and from thence to my Little Neck hovel. I’m glad I surveyed Flushing Avenue in 2004 — I think the FNY page I produced then captures it in its post-Navy Yard miasma perfectly. The jail that was then being torn down has vanished without trace, with a new building constructed over its corpse. On this trip, though, I was able to see a few things I overlooked back then.

My itinerary took me from the High Street A/C station down Adams Street to Tillary, Prince, Myrtle, Navy, then east on Flushing Avenue. A walk through the lengthy corridors of the High Street station reveals some outdated signs. For once thing the High Street station doesn’t stop at High Street, which once ran from Fulton Street east to the Navy Yard at Navy Street, but the mid-century Brooklyn-Queens Expressway and Farragut Houses, as well as Cadman Plaza Park itself, have reduced it to a one-block stretch between Pearl and Jay Street, and that stub is a full block east of the station. There are exits on Adams and in Cadman Plaza.

Though NYC has tried its best to standardize and unify subway signage, IND signs (like those above), which were tiled into the walls, resisted removal and were left in place. In other instances, modern black and white signs were simply affixed over them. In the 1990s, the worth of classic tiled signs was reassessed, and many of them were restored. But the hanging serifed signs vanished forever.

One of Brooklyn’s lest-known and perhaps least-visited WWI memorials is at Bernard Weinberg Triangle, Tillary Street and Flatbush Avenue Extension. This was originally the corner of Tillary and Bridge; Flatbush Avenue would be “extended” when the Manhattan Bridge opened in 1909. The 12-foot tall stele is engraved with the names of over 100 soldiers from the neighborhood who perished in the “Great War.” Six 20-inch tall artillery cases stand to the right of the monument, which is in a windswept and deserted plaza on a cold January day. (The internet is silent on the identity of Bernard Weinberg, so help me out if you can.)

Tillary Street was named for Dr. James Tillary, a colonial-era area physician. In the 1950s it had several extra lanes added when the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway was constructed nearby.

Two of Brooklyn’s tallest towers, The Brooklyner (311 Lawrence) and 388 Bridge, can be seen from Tillary looking south on Bridge. On the right is George Westinghouse Vocational and Technical High School. It was built in 1910 and designed by prolific school architect C.B. J. Snyder. Alumni include rappers Busta Rhymes, DMZ, Notorious B.I.G. and Jay-Z.

Center median of Tillary at Gold Street. This stanchion is a relic from the early days of the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway; until recently (<10 years ago) it still carried a black on white sign. It still uses incandescent bulbs to illuminate the sign.

The “Tillary Street Tigers” fight fires out of Engine 207, at Tillary and Gold Streets. Engine Company 207 was organized on September 15, 1869 as Engine 7 of The Brooklyn Fire Department, and reorganized to Engine 207 on January 1, 1913. The present firehouse was dedicated (Kiff, Voss and Franklin, arch.) in 1971 by Mayor John Lindsay.

Queens Midtown Tunnel directional sign. As a rule, signs pointing to bridges were arrow-shaped, while those pointing to tunnels were circular. It’s odd that the old Department of Traffic would direct traffic to the QMT here — it’s miles away in Hunters Point. A motorist could turn around and jump on the Manhattan Bridge easily from here, and with favorable lights, could be in Midtown a few minutes after crossing the river, if the traffic isn’t jammed.

These two photos show the south side of Myrtle Avenue between Prince Street and Flatbush Avenue Extension, in 2014 and about 2003. The 38-story Toren luxury apartment tower was constructed from 2008-2010, replacing the buildings in the bottom photo (from the mid-2000s), which were there when the Myrtle Avenue El still rumbled past.

Designed by the architectural firm Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, Toren contains studios, one- and two-bedroom units. Penthouse accommodations begin at the 30th floor and include one-, two- and three-bedroom residences, many of which feature double-height ceilings. Kitchens are equipped with custom cabinetry and modern appliances and bathrooms have floor-to-ceiling tiles and walk-in showers.

Notable Toren amenities include an indoor pool with a dedicated family swim time; a fitness center with a sauna and state-of-the-art equipment; a lobby attended by a doorman; a library with a wet bar and kitchenette; and a roof deck fit for entertaining. Moreover, it is close to the neighborhood’s boutiques and restaurants, as well as public transportation. CityRealty

I like the Toren, since it features protuberances that resemble bolt heads. I’d need to hit Megamillions to afford a place in there though.

I recognized this as art by Duke Riley, artist and speakeasy owner, who has created some of the art seen on the NYC subway. With his girlfriend, Tide and Current Taxi’s Marie Lorenz and “Movie Mike” Olshan, he infiltrated Coney Island Creek’s Yellow Submarine a few years ago, and launched a wooden submarine from Red Hook in 2007.

Turning north along Navy Street, a bicycle path accompanies auto traffic along its route through the Raymond Ingersoll Houses (named for a 1930s Brooklyn borough president), which intriguingly still have their original blue and white enamel signs. A rickety pedestrian overpass spans Navy Street, which has proven to be occasionally dangerous for bicyclists, as local youths occasionally like to drop things on them, for the fun of it all.

Of course, the situation could be alleviated immediately by installing a circular fence like this one, which prevents local youths from dropping things onto the Prospect Expressway from 10th Avenue in Windsor Terrace. However, common sense situations are rare in NYC.

Also notice the “Hudson Avenue” sign affixed to the lightpost. It’s completely wrong, as Navy Street ends as Hudson Avenue several blocks north in Vinegar Hill, but not here.

What is apparently an art installation spans the Navy Street sidewalk as it runs under the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway. These things resemble the orange Gates installations that the famed artist Christo installed in Central Park in the winter of 2005.

Flushing Avenue and Barry Park

Flushing Avenue begins at Navy Street as an eastern extension of Nassau Street. The avenue is unusually named, since we are miles away from Flushing, Queens. I have a detailed exigesis about why the road is so named on my first Flushing Avenue page, but it was named Flushing Avenue as early as 1855. Originally it extended as far east as Broadway, and east of that ran the colonial-era Brooklyn and Newtown Turnpike, which had been graded as early as 1813. Sometime along the way, Flushing Avenue was extended along the old turnpike’s route, and so ran all the way to Grand Street, which was extended across Newtown Creek in the 1870s.

Brooklyn’s oldest park, named for Commodore John Barry, can be found at Navy and Flushing Avenue, across the street from Officer’s Row (see below). What was originally City Park (when Brooklyn was a city) is indeed Brooklyn’s oldest, dating back to 1836 and renamed in 1951. Commodore Barry (1745-1803), known as the “father of the American Navy,” was born in Ireland, went to sea as a youth and quickly rose in the ranks from cabin boy to captain of the shipping vessel Black Prince. He served with success in the American Revolution, making the first American capture at sea of a British vessel, and made several others during the war; the sale of these vessels helped fund the nascent US Congress. In 1781 he escorted the Marquis de Lafayette on a mission to America. Barry helped found the Brooklyn Navy Yard in 1801, which constructed US vessels until 1966.

Commodore Barry Park is really a tale of two parks. The western end, shown above, seems largely unattended to, with lightposts along an east-west walkway broken and crumbling. However…

The eastern end of the park, which features a swimming pool, has been newly landscaped, with new murals depicting scenes from Fort Greene.

The World and Commodore Barry Park. Long ago, some neighborhood kids painted maps of the world’s continents, the USA, and Brooklyn into the concrete playing field. There’s even a star on the Brooklyn map pointing out the location of the park. The lack of upkeep and renovations has preserved them over the years, albeit in sun-faded glory.

Officers’ Row

The New York Naval Shipyard, known popularly as the Brooklyn Navy Yard, was established by the federal government in 1801. Robert Fulton’s steamship Clermont was built here and launched in 1815; the battleship Maine in 1890, as well as the first angled-deck aircraft carrier, the Antietam, were also built at the Navy Yard.

The Navy Yard at its peak just previous to World War II employed 10,000 workers. It has 5 miles of paved streets; 4 dry docks (including the nation’s oldest, which began construction in 1840) ranging in length from 326 to 700 feet; two steel shipways; and six pontoons for salvage work. The Navy Yard was decommissioned in 1966 and is now a center for private manufacturing, industrial parks, and movie studios and is still, unfortunately, closed to the public except for weekend bus tours.

Sadly, apart from the 1806-1807 Commandant’s House, possibly designed by Charles Bulfinch, on the northern end of the complex abutting Vinegar Hill , most of the Navy Yard’s old officer’s quarters, known as Officers’ or Admirals’ Row, some dating from the mid-to-late 19th Century, have been allowed to rot. They look out over Flushing Avenue between Navy Street and Carlton Avenue, their windows ivied and hollow. The Navy Yard does include the landmarked Surgeon’s House, built in 1863 for the Navy Yard’s chief surgeon, and the United States Naval Hospital, built from 1838 to 1862.

There has been a plan to demolish most of these buildings and build a shopping center in their place for the better part of a decade (as of 2014). Most of these buildings have now deteriorated so badly since I first began to monitor them in the late 1990s that it’s insulting to the US Navy and the commanders who once lived in these buildings to allow them to stand. Tear them down and salvage whatever can be salvaged. The latest plan calls for all but one (Quarters B) as well as a surviving timber shed to be torn down.

[US Army Corps of Engineers Archeological Report]

The Farragut Houses, seen from the corner of Flushing Avenue and Navy Street. When built in the mid-20th Century they were appropriately named for Civil War-era Admiral David G. Farragut:

The first Admiral of the U.S. Navy, Farragut was one of the most colorful commanders of the Civil War. He was the most famous Hispanic on the Union Forces during the war. He was born James Glasgow Farragut, son of seafarer who came from an island off Spain. David Porter, a navy officer adopted him after the Farraguts saved Porter’s unconscious father from a drifting boat. He changed his name to David Glasgow Farragut. He went to sea with Porter at age 8 and became a midshipman before he was 10. He saw combat at 11 and commanded his first ship at 12. In 1864 he was summoned from New York to lead the attack on Mobile Bay, the last Confederate stronghold on the Gulf of Mexico. When one of his lead ships struck a torpedo and sank and his ships were reluctant to proceed, he rallied his men to victory, shouting: “Damn the torpedoes! Full speed ahead.” Farragut Houses is across from the Navy Yard in Brooklyn. NYCHA

Fort Greene is the home of Sweet’n’Low, with the artificial sweetening product, manufactured by Cumberland Packing Corp., headquartered at 2 Cumberland Street (at Flushing Avenue) with additional facilities inside the Brooklyn Navy Yard, manufactures Sweet’N Low, Sugar in the Raw, Nu-Salt, and other products. Over 500 billion packets of the sweetener have been produced since the founding of the company by Ben Eisenstadt in 1957. Cumberland Packing was also the first company to introduce sugar packets, which ultimately replaced the sugarcubes in a bowl model that had previously dominated dessert tables.

Another venerable factory building on the east side of Cumberland and Flushing that preserves a number of architectural details, including a smokestack, now is home to M&D Door & Hardware, which also owns space in the old Navy Yard across the street.

A number of classic brick Navy Yard buildings are visible from Flushing Avenue. The Navy Yard’s Building 92, at Carlton Avenue, is one of the few of the old residential buildings that has been renovated and reused:

Building 92, the former Marine Commandant’s residence, designed in 1857 by the fourth architect of the U.S. Capitol, Thomas U. Walter, serves as the Yard’s public face, gateway, and ambassador, and home of the first major exhibition to tell the story of the Yard. After the federal government decommissioned the Yard in 1966, the stately building sank into advanced disrepair. BNYDC seized the opportunity to preserve the historic structure for an exemplary demonstration of creative adaptive reuse. The new design weds the renovated historic structure to a 4-story modern extension that houses BNYDC’s Employment Center, leasable space, classrooms and meeting/event space. The entire site has received LEED Certification- Platinum Status from the US Green Buildings Council, the highest designation for sustainable buildings. Building 92

Building 92 is the Navy Yard’s “public face” and you can book weekend bus tours of the vast space through its website.

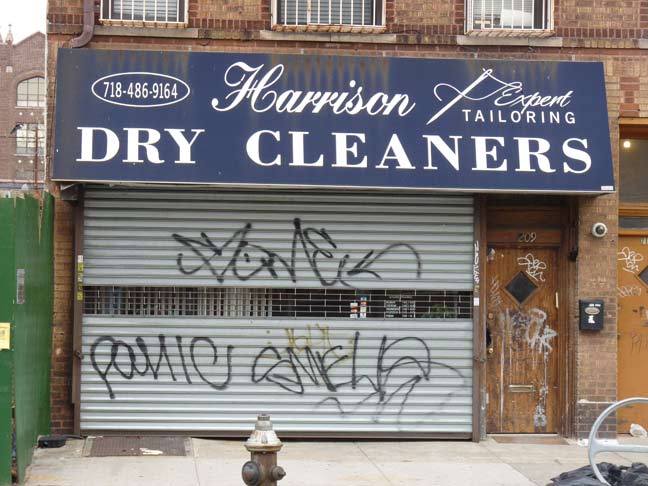

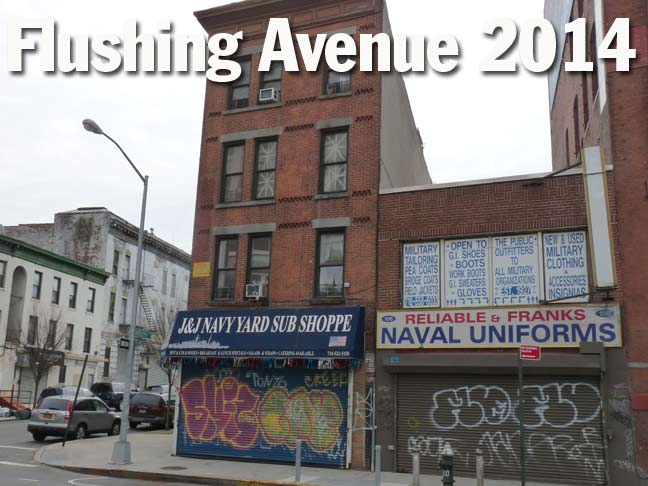

A pair of businesses at Flushing and Adelphi Street that catered to the old Navy Yard trade, or at least are named for them.

I’ll repeat the item I had for Reliable & Frank’s from my previous Flushing Avenue page:

Though there aren’t many sailors at the Navy Yard any more with its decommission in 1966, Reliable & Frank’s Naval Uniforms is still where it’s been since 1927.

“You don’t get much foot traffic,” said Vincent Faiella, whose grandfather Natale Faiella opened the store in 1927 and whose father, “Battleship” Mike Faiella, ran it before passing it on to Vincent.

Battleship Mike, who is 77 and lives on Ocean Parkway, visits a few days a week. “Business isn’t what it was,” he said laconically, sitting on a folding chair and surrounded on all sides by mounds of royal-blue trousers.

At the height of the Navy’s presence in Brooklyn, during World War II, dozens of surplus stores were located near the yard. Today, only Reliable remains. “We were able to get into different avenues,” said Battleship Mike, noting that in the 60′s and 70′s the Army-Navy look was big with “hippies.”

Later, Reliable sold uniforms to workers on cruise ships, to the crew of Malcolm Forbes’s yacht, to budget-conscious students at Pratt Institute and to the Village People (for the group’s “In the Navy” video, naturally).

Each time a rival closed, Reliable bought it out and appropriated the old stock, along with some facet of the business. Taking over a store named Battleship Max Cohn is how Battleship Mike got his nickname.

That strategy of expansion has resulted in a huge inventory: work shirts, wool socks, camouflage coats, patches, pins, a kimono dating to World War II, and what Vincent Faiella suspects is the country’s largest inventory of Seafarer Dungarees, the bell-bottom jeans once worn by sailors. NY Times

That was from 2006, and the business has since closed…

Alexis Robie got some interior photos.

Navy Yard Building 120 opposite Carlton Avenue. The internet seems to be silent about this structure, but from its length I may be able to guess that it might have been used for the manufacture of rope or, perhaps, firehoses, but that’s conjectural.

At Clinton Avenue, I remember the Maferbo Clothing hand lettered signs from my first walk here. Unlike Reliable & Frank’s, Maferbo appears to still be in business. The billboard above reminds me of Jerry Johnson’s fake signs that formerly appeared at Nevins Street and Atlantic Avenue in Boerum Hill in the 1990s.

The Clinton Avenue gate is one of the Navy Yard’s main entrances, along with the Sands Street and Washington Avenue entrances, complete with a pair of stone eagles on either side. There’s a CitiBank® bike rack just inside the entrance, but don’t let that fool you; a hawkeyed security guard is also in a booth a few feet into the entrance. A shield sign (one of many) still claims the Navy HYard as US Government property; it’s as closely guarded as if it were.

CitiBike® rental stations, sponsored by the bank, are frequently found in northern Brooklyn. Bikes are available for daily or weekly use, but you have to use your credit card.

This combination apartment building at Washington Avenue with a coffee shop on the ground floor sports the elaborate architectural treatments of the late 19th Century and the glass walls of the 21st Century. In 2014 it hosted the Brooklyn Roasting Company…

… until just a few years ago it was the raunchy and a little bit dangerous JJ’s Navy Yard Cocktail Lounge.

Once catering to the men who built warships for World War I and II, in its final days, it continued to serve as a second home to locals and Navy Yard laborers. So not much changed here between 1907 and 2010–except maybe for the addition of scantily clad dancing girls. Jeremiah’s Vanishing New York, which has added photos.

JJ’s Navy Yard Cocktail Longe [EV Grieve]

Steiner Studios has developed into a major moviemaker since moving into its 20-acre, 10-soundstage complex in the Navy Yard in 2003, at the largest movie studio outside of Hollywood.

Among the major motion pictures filmed at Steiner Studios are The Producers: The Movie Musical, Fur, Then She Found Me, The Tourist, Across the Universe, The Hoax, Funny Games, The Nanny Diaries, Life Support, Spider-Man 3, Men in Black 3, Mr. Popper’s Penguins, The Adjustment Bureau, Sex and the City 2, The Tempest, Revolutionary Road, My Super Ex-Girlfriend, Inside Man, Enchanted, Baby Mama, The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, and Burn After Reading.

Steiner Studios also has hosted many television series, including, Damages, Flight of the Conchords, Clash of the Choirs, The Unusuals, Pan Am, Bored to Death, Boardwalk Empire, Girls, and Hip Hop Squares. wikipedia

Beyond this Washington Avenue entrance you can see some of the nondescript, cookie cutter housing that has sprung up in Williamsburg over the last decade.

While passing by on January 1st, 2014, just about the only business that was open in the vicinity (except for Brooklyn Roasting Company) was The Kosher Café on Hall Street. Both Orthodox and non-Orthodox customers were going in and out, probably working at the nearby offices. South Williamsburg has been home to Orthodox and Hasidic Jews for many years.

ForgottenFans know of my preference for stolid brick buildings. 33 Hall Street is one such and I couldn’t resist a brief detour. The building is home to knitwear and furniture factories among others.

Toward the eastern end of the Navy Yard on its Flushing Avenue frontage, there are some perpetually barbed-wire entrances and weed-encrusted buildings. I’m frustrated about not being able to enter the Navy Yard at my leisure just so I could get better close-up photos of its historic buildings and ruins. I don’t think a 2-hour bus trip would fill that bill.

There are a couple of cross streets that don’t look interesting on the face of it, but do have some historical connections. “Ryserson” doesn’t look Dutch, but it’s a modified form of the Dutch family the Ryerszens, who settled in the area in teh 1600s and originally owned much of the land that later became the Clinton Hill neighborhood.

The only remaining residence that poet/author/editor Walt Whitman lived in in Brooklyn can be found at #99 Ryerson Street.

Flushing Avenue is lengthy enough that it intersects both the Grand Avenues in Brooklyn and Queens. Brooklyn’s Grand Avenue runs south from here to Washington Avenue and Park Place in Prospect Heights, interrupted by the Pratt Institute campus. From 1888-1950, it supported Brooklyn’s Lexington Avenue elevated line between Myrtle and Lexington Avenues.

Flushing Avenue ends at Grand Avenue in Maspeth, which is an eastern extension of Brooklyn’s Grand Street along the old Brooklyn and Newtown Turnpike.

Detouring around another corner, I found a couple of massive Deco storage buildings at Kent Avenue and Little Nassau Street, a short alley that runs from Taaffe Place east one block to beyond Kent.

I read that “Taaffe” is actually an Irish name; with the double A, I’d guess Dutch. How is it pronounced? Taf, or taffy?

Northern Brooklyn boasted many breweries beginning in the 19th Century. Schaefer, the last of the classic breweries, shut its doors on Kent Avenue in 1976, though microbreweries have sprung up here and there ever since. This massive building on Franklin and Flushing was once the Malcom Brewery, instituted by Scottish immigrant George Malcom. The oldest part of the building went up in 1869. Much of the building was designed by Otto Wolf, a German immigrant who specialized in breweries. Montrose Morris has the whole story at Brownstoner.

Some handlettered signs on Flushing Avenue and Warsoff Place.

Many of the buildings along Flushing Avenue between Marcy and Tompkins Avenues are emblazoned with signs denoting the Pfizer Company. The drug manufacturer was opened by Charles Pfizer and cousin Charles Erhart in 1849 on Flushing Avenue, with its first product being santonin, a drug originally used to expel roundworms from the system. It moved its main headquarters to Maiden Lane downtown in 1868; it has frequently moved around since and has branches worldwide. Its production of citric acid in 1880 became its main business for decades; Pfizer pioneered the production of penicillin in 1941. It would become the world’s #1 maker of the new wonder drug during World War II. Among the well-known brand-name drugs produced by Pfizer today are Advil, Celebrex, Lipitor, Viagra, Xanax and Zoloft. Today the complex is home to “artisanal” food producers and schools. Pfizer sold its Brooklyn properties in 2011.

Why is there a building on an angle at the corner of Flushing and Tompkins Avenues? Because it used to face a vanished street that once ran past. In fact, the street is still marked on a lamppost. See this FNY page for the details.

This awning sign on nearby Harrison Avenue makes good use of the near-forgotten Bodoni font, which many designers seem to avoid these days since it’s so old-school.

Looking west from Harrison Avenue and Bartlett Street toward the Pfizer buildings on Flushing Avenue.

This boarded up building on Bartlett Street northeast of Harrison is a reminder of the bad old days of Bushwick and northern Bed-Stuy after the 1977 summer blackout, when looters, rioters and arsonist landlords combined to scorch its earth for nearly 20 years. Only now is the neighborhood struggling back. Empty lots line Bartlett street in the block between Harrison and Throop Avenues.

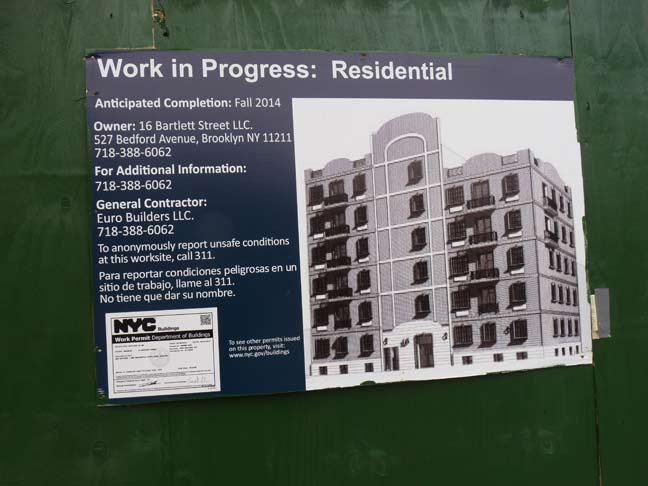

A new residential tower is planned on the other side of the street. What a view they’ll have.

Another old-school empty lot on Flushing Avenue east of Harrison. In the summer, it’s at least green, with the weeds.

Painted sign (1970s?) for Batista Refrigeration. Very nicely done, and every word is spelled right.

Approaching Broadway, the beetling, intimidating facade of Woodhull Hospital comes into view. Interestingly, the name honors a long-vanished property owner:

In 1967, Mayor John Lindsay and Governor Nelson Rockefeller envisioned a ‘dream’ hospital for North Brooklyn to replace an older, obsolete public hospital located in Greenpoint. The facility was to boast several levels of care, single bedded rooms, and the same amenities for public hospital patients as those enjoyed by private hospital patients…

… The hospital’s name was the result of an essay contest held in local schools. The winner of the $25.00 prize was Victor Morales, an Intermediate School 318 student and community resident. In his prize-winning essay, Mr. Morales traced the origins of the original landowner of the immediate area, whom he identified as Richard M. Woodhull. Mr. Woodhull was credited with having laid out the Village of Williamsburg into an actual city. In 1970, Mr. Morales turned the first shovel of dirt at the groundbreaking ceremony.

The City’s financial crisis of the 1970’s delayed the opening of the ‘dream’ hospital until 1982, when it began providing primary care and inpatient services to the community. Woodhull Medical Center

The old Greenpoint Hospital’s buildings are still there, on Maspeth Avenue and Kingsland Avenue.

What is now a seemingly unmarked mystery church at Flushing and Throop Avenues is All Saints Roman Catholic Church, constructed in 1894 for a mostly German immigrant parish that had existed since 1868. The stained glass windows are more recent additions and depict the site at Tepeyac, Mexico, where the faithful believe Saint Juan Diego met the Virgin of Guadalupe in December of 1531.

I continued further on this walk, but that kicks it in the head for now.

2/2/14

12 comments

The origin of the name Taaffe is hard to determine-there was an Austro-Hungarian Count by that name.I knew a cop with the same last name-I’m not sure if he spelled it exactly the same though.

My father worked at the Brooklyn Navy Yard prior to WWII. At the beginning of the war selective service deemed him too valuable for military service until about 1943 when he was drafted into the US Navy. Due to his experience as a ship fitter he became a petty officer after he completed basic training. He was asigned to the navy yard in Bremerton, WA where he repaired many battle damaged ships. After the war he was discharged & his father-in-law, my grandfathger, a WWI veteran, advised him that ship building was out & furniture was in. This was good advice, since the Brooklyn yards closed in 1966 but his custom upholstery business (Marland Decorators in Parkchester) survived until his retirement in 1993.

The rapper who went to the Technical & Vocational High School is DMX, not DMZ.

In a map from 1938 Building 120 is called “oil house” and one from 1961 states a post office, supply sales, and a cafeteria housed in the building.

http://www.trainweb.org/bedt/milrr/bny.html

Thanks for the photo tour. Although I grew up in Queens I had a long history in that part of Brooklyn. My dad worked for Pfizer for 35 years and I went to high school at All Saints Commercial Girls HS (the mystery church) would have graduated in 74 but the school closed down in 73. I remember the church was very beautiful. Years later I lived in Williamsburg now a resident of Rhode Island. Thanks for the memories.

Kevin, nice pix of some of my old stomping grounds. A bit farther along from the weed covered gate there is a tin sign on a building that reads, Brooklyn Navy, Motion Picture Exchange in rear, Shipping and Receiving in rear.

J. J.’s Lounge was catty corner from the last Navy building in the Navy Yard. When I reported to USS Thorn at Coastal Dry Dock the corner building was used by the Navy for admin functions and included a post office and barber shop. Even then I avoided places like J.J.’s like a plague. I had to pass by on my way to the High Street subway stop on my way to and from manhattan. I admit I had eyes for the jazz clubs in midtown and the Village and spent little or no time forgottening. I regret that now because I could have spent some time exploring the old yard but the bright lights attracted me.

Thanks for the vocabulary lesson – learned 3 new words from this entry: stele, exigesis and beetling.

Correction: exegesis

.

.

When I got back from VietNam, in November 1968, The Old Man took me down to Flushing Ave to get me a set of Dress Blues — The aged Jewish tailor fitted me like I was the Commandant of the Marine Corps!!! —

Im looking at all these photos and they bring back so many memories, I lived in these areas from 1956 until 1972

Thanks so much for this great tour. I am researching my grandparents from Brooklyn, they lived on Ryerson for a bit and my great-great grand father ran a metals junk yard at what was “44 Flushing Avenue.” He was sent to jail for accepting stolen metals from the Navy Yard around 1910, shortly before his death in 1918.

I just happened upon your post. I grew up in Fort Greene and I have always been a history enthusiast. I wish i had taken pictures as i was growing up to look back on what was. I enjoyed reading about what you have noticed and learned. I loved it. I think I will go and take a walk and some pictures of what i remeber this weekend.

Thank you!