photo: Wayne Whitehorne, courtesy NYC Subways

When it was opened on February 11th, 1933 as part of the new Independent Subway System, the High Street station on today’s A and C lines, the first or last station in Brooklyn depending on your direction, was indeed located on High Street. When the east-west street was laid out in the 1820s it ran continuously from Fulton Street, which wound circuitously to the Fulton Ferry on the East River, east to Navy Street, which bordered then and now on the Brooklyn Navy Yard. However, no east-west street in downtown Brooklyn has been sacrificed to real estate and transit concerns more than High Street. Its first interruption came in the mid-1900s, the 20th Century’s first decade, when a section between Jay and Bridge Streets waa demapped and became part of the Brooklyn plaza of the Manhattan Bridge.

In the 1940s and 1950s, all of High Street between Bridge and Navy Streets came off the map, demolished to make way for the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway and the Farragut Houses. Today, only one block of High Street remains between Pearl and Jay.

Toward its western end, High Street served as a terminus for el trains traveling to and from Manhattan via the Brooklyn Bridge at the massive Sands Street terminal shed. As early as the 1930s, a large park was under construction between Fulton and Washington, taking out High Street’s western end.

Downtown Brooklyn’s aspect utterly changed, and Fulton Street lost much of its old personality, when entire blocks just east of it were razed between 1950 and 1960 to make way for Samuel Parkes Cadman Plaza, which served to add a lot of green to downtown Brooklyn, which was, admittedly, needed. (The el had already come down in the early 1940s).

Samuel Parkes Cadman (1864-1936) was a Methodist minister and leader of the Central Congregational Church in Brooklyn from 1901 till his death. It was Rev. Cadman who called the the Woolworth Building in Manhattan the “Cathedral of Commerce.” Cadman Plaza provides views of the Manhattan Bridge from the steps of Borough Hall and allows a vista looking toward the beautiful US Post Office Building on Tillary Street, which was much harder to see before the blocks had been cleared out. Perhaps inspired by Cadman Plaza, Boston scuttled its old seedy Scollay Square in favor of the new Government Center in the early 1960s. There’s a kind of forced stillness about Cadman Plaza; it just seems like a plot of green that has been plopped into a neighborhood that didn’t really ask for it.

The construction of Cadman Plaza caused Fulton Street to be renamed as Cadman Plaza West from the ferry landing to Court and Montague Streets. Washington Street, on the eastern end, was renamed Cadman Plaza East. Calling Fulton Street Cadman Plaza West from the old ferry landing southeast to the Brooklyn-Queens expressway made no sense whatsoever, because Cadman Plaza extends from Borough Hall only as far north as the BQE. The city recognized this anomaly in the late 1970s and re-renamed that section of Fulton Street as Old Fulton Street.

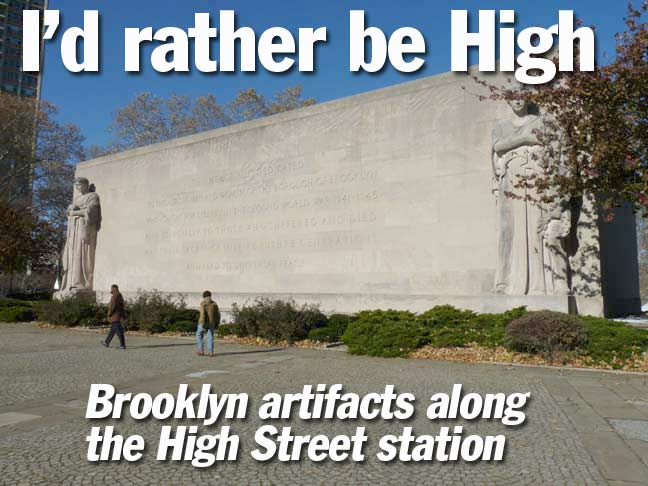

The soccer pitch seen here is the most “parklike” section of Cadman Plaza, and sits just south of one of the plaza’s major memorial works: The Brooklyn War Memorial.

This is a massive, granite and limestone monument dedicated to World War II casualties designed by Stuart Constable, Gilmore D. Clarke and W. Earle Andrews, with allegorical depictions of family and bravery by sculptor Charles Keck, who passed away the same year they were unveiled, in 1951. It was part of a 5-borough plan by Parks Commissioner Robert Moses to construct five WWII monuments in each borough, but only Brooklyn’s was completed. Brooklyn’s war memorial was originally planned to be even more massive, with a central auditorium flanked by two wings, but it was scaled down for materials and money shortages.

The real artifact, though, isn’t the memorial itself but what’s under it. Today the memorial contains administration offices and rest rooms in the basement. And there’s something else of interest.

Adjacent to the men’s room, there’s a pay phone, but it’s not just any pay phone.

This just may be the last rotary dial public pay phone in existence, though of course, there’s no way for me to truly know. Undoubtedly there are rotary dial phones in phone booths clinging to life in private residences, restaurants and bars. The NYC Public Library on 5th Avenue still has wood phone booths, though I have not checked for rotary dials.

This specimen is so old it still has a 212 area code on its dial, and an affixed Bell Atlantic logo. Bell Atlantic existed between 1984, when it was formed after the breakup of the AT&T/Bell system monopoly, and 2000, when it merged with GTE to become Verizon.

Rotary dial phones have been in existence since 1892, when a patent for the dial was obtained by an undertaker named Almon Brown Strowger. However, the rotary dial didn’t assume its present shape until a variety with holes for fingers was introduced in 1904 and finally saw widespread distribution in 1919. The dial was phased out beginning in the 1960s when pushbutton dialing was introduced. The first TouchTone phone appeared at the Seattle World’s Fair in 1962.

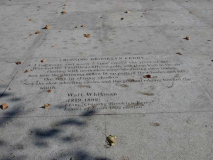

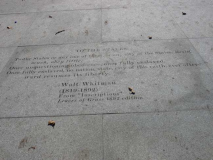

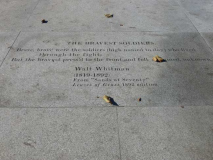

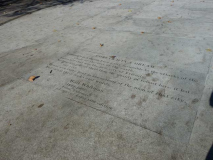

East of the memorial on Cadman Plaza East, there is a relatively new park dedicated to Walt Whitman, the great journalist, poet, and witness to the 19th Century.

East of the memorial on Cadman Plaza East, there is a relatively new park dedicated to Walt Whitman, the great journalist, poet, and witness to the 19th Century.

Best known for Leaves of Grass, the revolutionary collection of twelve poems that first appeared in 1855, as well as “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry” and “I Sing The Body Electric,” Walt Whitman was born in West Hills, Long Island, in 1819. The young Walt worked as a typesetter and pressman in the 1830s for a couple of Brooklyn newspapers. After trying his hand at fiction in the 1830s, he took over as editor of the Brooklyn Eagle in 1846, a post he would keep until 1848, leaving in a dispute over abolition (Whitman was anti-slavery, Eagle owners weren’t. The Eagle continued to publish until 1955).

In 1861, Whitman would move to Washington, DC, to aid in the Civil War effort (he worked as a nurse’s aide in a hospital) and would not spend as much time as he used to in New York City…but not before penning a series of essays published in the Brooklyn Standard called his Brooklyniana.

It was Whitman who proposed Fort Greene Park surrounding the memorial for soldiers who perished on British prison ships anchored in Wallabout Bay, and his only remaining Brooklyn residence stands at #99 Ryerson Street.

Just outside the park on a Cadman Plaza East lamppost is affixed one of Brooklyn’s last remaining color-coded vinyl/metal street signs, which first appeared in 1964; the Department of Transportation commenced a phaseout in 1984 and converted to green signs in most areas. In the 1950s, Washington Street between Johnson and Prospect Streets was renamed Cadman Plaza East.

A short piece of High Street between Washington and Adams was renamed Red Cross Place in the 1950s, as the Brooklyn headquarters of the worldwide relief agency was located there. The street, and this painted sign in the station remain, but the HQ does not.

11/24/14

8 comments

Talk about extremely rare finds! The rotary dial and 212 area code are not the only things making that make that payphone a unique antique. At least part of that phone, the upper housing, pre-dates 1969-1972! At the bottom right of the 4th photo, there is a Bell System logo that most people no longer recognize. It was replaced as the corporate identifier in 1969 and for the most part (trucks, directories, signs, etc.) was phased out by 1972. It was replaced on payphones (and everything else Bell) by the also long gone (except for a few Verizon vehicles), modern (1969), bell Bell System logo.

Let’s roll back the clock a little further, are there any 3-Slot (Multi-Coin) payphones (coin collectors) left hidden anywhere in NYC that escaped the late 60’s/early 70’s purge?

Good observation about that Bell logo.

Bell Atlantic was around since the Bell breakup in 1984, but they were not New York’s telephone company until 1997, when they merged with NYNEX. The area code for NYC’s “outer boroughs” had been changed to 718 some years before that (the final step taken in 1993). So I am thinking there may have been a “718” sticker over the 212 on that dial at one time, and that it later peeled off. Anyway, a functional pay phone has to receive regular visits from the telephone company, if only to collect the coins in the coin box. So presumably this phone, with its rotary dial and obsolete signage, is being left as is quite deliberately.

And of course, I remember the previous model of pay phone with the three separate places for putting in nickels, dimes and quarters. They weren’t exactly “slots”, but circular openings each the size of the coin it was intended to accept, into which the coins would be placed and then released.

Did you try calling the phone to see if it works? Looks to be maintained as it has Verizon information on it too. Very rare indded!

I tried it. Number not in service.

During the late 1990’s, the phone company did not allow you to call one of their pay phones; unfamiliar about COCOTs. I can not recall whether you received a message, or a fast busy signal. Any enterprising drug dealer could set up shop with just a public pay phone.

The 625 exchange is for the Bridge St. Central Office.

I remember our old rotary phones from the 50’s. The had steel rotary dials rather than the new plastic ones. I think Henry Ford had a hand in the design, because you could have any color as long as it was black.

As I recall, the Red Cross was located in the building backing the war memorial during the 50s until at least the early 60s, and located in the same building was a branch of the Police Athletic League (PAL), which, during my couple of visits, seemed pretty deserted, causing me to wonder about its purpose. Certainly nothing of interest for a straight arrow like me.

The phone has been modernized to accept credit cards and phone cards, so I agree the rotary dial must be left there as a deliberate anachronism. Maybe because it’s a World War II memorial, and rotary dials were in use (at least in cities) at that time. Or maybe I’m reading too much into it!