On a late winter Sunday in February 2015, cabin-fevered from weeks of cold and ice (I complain equally bitterly about summers when they are hot and humid for weeks on end) I took the LIRR to Flushing Main Street, exited the train and walked the length of Kissena Boulevard, which runs from Main Street just south of the railroad overpass to Parsons Boulevard and 75th Avenue. A tidy little 2 to 3-hour adventure.

I also consulted old photos and maps, since I knew that the boulevard evolved from a rural route that connected Queens’ two largest towns, Flushing and Jamaica Avenue, but ran through rural farms and fields to do so. Presently, the route runs past flocks of high-rise apartment houses but also the open fields of Kissena Park and the fairly expansive Queens College campus, which still contains a number of buildings left over from when it was the grounds of the Parental Home.

My route today was prosaically simple, but it’s always nice to have a map, anyway.

Where was I? I was on Kissena Boulevard at the entrance to Kissena Park at Rose Avenue. But why is there a wrought-iron rendering of a locomotive on the fence? There’s a reason it’s there.

A lengthy gash of green known as the Kissena Corridor can be seen on Queens maps, running from Flushing Meadows-Corona Park at its western end all the way east to Cunningham Park at Francis Lewis Boulevard on the east. The Queens Botanical Garden between College Point Boulevard and Main Street forms its western end, while a narrow patch is slotted between Colden Street and 56th Avenue/56th Road, seen in the above photo on a recent February afternoon.

The gash “widens” into Kissena Park proper, which is divided into a “parklike” northern section and a more “natural” southern section, between Kissena Boulevard, Rose Avenue, Oak Avenue, Booth Memorial Avenue and 164th Street. East of that, the Kissena Corridor’s narrowest sector runs from Fresh Meadow lane to the Long Island Expressway, after several blocks’ interruption by the Kissena Golf Course between 164th and Fresh Meadow Lane.

The Kissena Corridor is there because it is the ancient right-of-way for a long-vanished railroad. In the early 1870s, Scottish immigrant and department store magnate Alexander T. Stewart purchased plots of land from local farmers and built the Central Railroad of Long Island as a means to connect western Queens with a new development of his, Garden City.

The railroad was a financial failure and survived for just a few years, yet the railroad, built over 140 years ago, still survives…after a fashion… as a park, which matches its fate with that of the High Line on the west side of Manhattan.

Just as we’re speculating about what would happen if the Long Island Rail Road Bay Ridge freight line through the heart of Brooklyn and into Ridgewood, Queens, could be fitted for mass transit, or perhaps the old Ozone Park to Rockaways LIRR branch, abandoned since 1962, could be used again for rail, it’s fun to speculate what would have occurred if Stewart’s line was a success. It would mean a direct connection from the LIRR Port Washington Branch to Garden City, serving the Queens communities of Fresh Meadows, Hollis Hills, Bellerose and Floral Park; the street grid in those areas, after over 140 years, still allows for a a railroad right-of-way! Oh well… the full second Avenue Subway will be built before any transit initiatives favoring Queens are even discussed!

Read much more on the Central Railroad of Long Island here at Art Huneke’s Arrchives.

Kissena Park itself lies on the former plant nursery grounds of Samuel Bowne Parsons, and does, in fact, contain the last remnants of their plant businesses. As stated in Part One, Parsons Boulevard is the road built in the 1870s that connected Parsons’ farm with that of Robert Bowne. A natural body of water fed by springs connecting to the Flushing River was named Kissena by Parsons, and is likely the only Chippewa (a Michigan tribe) place name in New York State. Parsons, a native American enthusiast, used the Chippewa term for “cool water” or simply “it is cold.” After Samuel Parsons died in 1906 the family sold the part of the plant nursery to NYC, which then developed Kissena Park, and the other part to developers Paris-MacDougal, which set about developing the area north of the park. Kissena Park attained its present size in 1927. Much of its southern end remains wilderness, with bridle paths running through it.

It’s also the home of New York City’s only outdoor velodrome, where pro, semi-pro and proficient bicyclists can race or practice on a raised track. It was in fact used in 1962 for Olympic Games bicycling trials. The velodrome had slipped into obscurity and deterioration until about ten years ago when it was restored to glory. Coincidentally, or perhaps not so coincidentally, NYC was preparing its bid for the 2012 Summer Olympics, which were ultimately awarded to London, England.

Full FNY coverage of Kissena Park

Full FNY coverage of the Kissena Park Corridor

At the park, Kissena Boulevard, originally the main road between Flushing and Jamaica (and named Jamaica Road) takes a turn directly south, it had run southeast from Main Street in Flushing. No stoplights control the flow here, so reflective signs have been installed to avoid crashes into the park…

… at Peck Avenue, a single guy wire mounted blinking Cyclops signal warns traffic about the bend.

Peck Avenue runs along the south end of the Queens Botanical Garden for a couple of blocks. It’s one of the more unusual avenues in eastern Queens, as it runs through Flushing, Fresh Meadows, and Hollis Hills in five different sections; in its longest section, it runs south of Corridor Park, while Underhill Avenue runs along the north. At one time, Peck and Underhill were mapped out to the Nassau County line along the route of the Motor Parkway, but were never built that far.

Peck Avenue is named in honor of longtime Flushing resident and property owner Isaac Peck (1824-1894). He owned a department store in College Point for many years. Members of the Peck family are buried in St. George Churchyard on Main Street in downtown Flushing.

Kissena Boulevard passes by the southern, “wilder” section of Kissena Park, which boasts is bridle trails, serviced by the Western Riding Club on Pidgeon Meadow Road and 169th Street in Auburndale, which has been in danger of immediate closure for a couple of years.

The “twin towers” of the Electchester housing project can be seen looking south on Kissena Boulevard.

Electchester, a cooperative housing project located between Jewel/HVA Avenue, Parsons Blvd., 164th Street and 65th Avenue, was established by Van Arsdale and the Joint Industry Board of the Electrical Industry in 1949 on the grounds of the old Pomonok Country Club. Originally housing mostly electrical workers and their families (hence its name), Electchester is no longer exclusive to them:

The meat cutters had Concourse Village in the Bronx. The garment workers had Seward Park Houses in Manhattan. The printers had Big Six Towers in [Woodside], Queens. Decades ago, local unions sponsored more than a dozen cooperatives that provided almost 50,000 decent and affordable apartments to working-class families. As the power of labor waned and real estate values skyrocketed, though, most of these co-ops either lost their direct union connection or allowed their shareholders to sell their units on the open market. New York Times, March 15, 2004

The intersection of Kissena Boulevard and Booth Memorial Avenue is an old one, and has existed for over a century; it was formerly where two country roads called Jamaica Road and North Hempstead Turnpike met. The Turnpike, named for the former name of New York Hospital at its intersection of Main Street, once went as far east as Queens Avenue, now Hollis Court Boulevard, and not as far as the westernmost town in Nassau County for which it is named. (That intersection has been eliminated by the joint creations of Cunningham Park and the Long Island Expressway.)

Several of Hempstead’s original fifty patentees in the 1640s were Dutch, suggesting that Hempstead was named after the Dutch town and/or castle Heemstede, which are near the cities of Haarlem and Amsterdam. However, it is possible that the authorities had Dutchified a name given by co-founder John Carman, who was born in 1606 in Hemel Hempstead, Hertfordshire, England, on ancestral land owned by his ancestors since the 13th century. wikipedia

It’s still a puzzler why this old trace, which before it was called North Hempstead Turnpike was called Ireland Mill Road since on its western end it led to a now-vanished tributary of the Flushing River, received its old name. On its original eastern end, Queens Avenue could get you to the Hempstead & Jamaica Turnpike, now prosaically called Jamaica Avenue, which is the likely story.

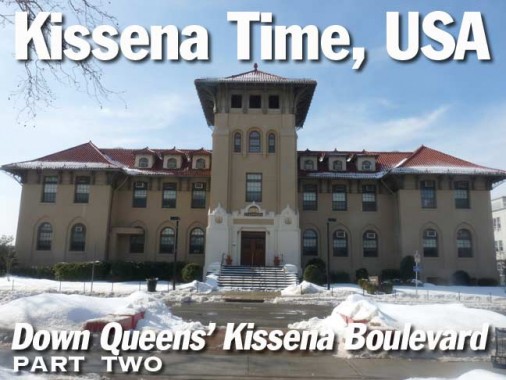

Just past the Long Island (Horace Harding) Expressway, Kissena Boulevard forms the eastern end of the main campus of Queens College, established in 1937 at the former grounds of the Parental Home, a home for “troubled boys.” The Parental Home, in turn, was established in place of the Jamaica Academy, established in the early 1820s. Long Islander journalist/poet Walt Whitman had served as a schoolteacher at the Academy briefly. The schoolhouse remained a part of the campus until 1935.

Six of the campus’s original nine Spanish Mission-style buildings have been retained till the present, including Thomas Jefferson Hall, above. They had been constructed for the Parental Home campus in the first decade of the 20th Century.

Jefferson Hall, like other buildings built for the Parental Home, was constructed by the prolific schools architect C.B.J. Snyder. The Hall, originally the H Building (campus buildings were simply alphabetized at the beginning) was designed with terra cotta ornamentation above the entrance, including six owls and two laughing schoolboys at the front and side entrances.

Another original QC building, Virginia Frese Hall, serves as the school’s Counseling, Health and Wellness Center.

Delany Hall is named after Dr. Lloyd T. Delany, who was a professor in the Psychology Department and was appointed the first African-American Director of the SEEK Program at Queens College. Established in 1966, the program was designed to reach qualified high school students who may not have the wherewithal to attend college.

The 11,400-square foot Margaret Kiely Hall, seen prominently from Kissena Boulevard, is the QC Administration Building.

At first I was put off by the Queens College Student Union Building; I dislike most Brutalist architecture of the Paul Rudolph sort, but I looked at the building more carefully and it grew on me, with its straight up and down lines. (I’m no architectural scholar or critic, but I know what I like and don’t like.) The recessed concrete panels reminded me of the Washington DC Metro subway system, where all the underground stations feature them.

The primary host for productions of the Drama, Theatre and Dance Department, Goldstein Theatre is located on the northeast corner of campus, at the intersection of Kissena Boulevard and the Horace Harding Expressway (L.I.E.). The theater is named in honor of QC alums Irving Goldstein, ’60, CEO of INTELSTAT, and his actress wife, Susan Wallack Goldstein, ’62. It is a 450 seat proscenium theatre with a 40 foot wide by 18 foot high proscenium arch. This theatre is equipped with an automated orchestra pit which can be lowered to 7’6″ below stage height, a fully computerized lighting system installed in 2006, and ample wing space on both sides. –Queens College

Big names in music and theater appear at the The Kupferberg and Colden Centers in the campus’s northeast corner at Kissena Boulevard and the LIE.

One of these weeks I’ll have to do a more thorough survey of Queens College’s architecture, since it ranges from the mission-style campus buildings left over from the home for wayward boys all the way through to the 21st Century’s streamlined, computer-age facilities. Since the school is built on a hill, it also has a fine view of the distant Manhattan skyline.

A pair of lampposts on one of the campus roads near the KIssena Boulevard entrance look like mini-versions of the finned Whitestone Bridge lamps, which until the 1960s were standard issue on NYC parkways (they were the successors to the wooden posts). A few of the originals can still be seen around town, especially at either side of the Brooklyn Bridge.

Also at the same entrance gate is a very well preserved specimen of metal and enamel Brooklyn street sign typically seen in the 1950s and 1960s before vinyl versions overcame them. This one was likely produced by the same firm. The signs feature a black background with raised white letters in a Highway Gothic condensed font.

When I saw the name at the roofline of this brick building at Kissena Boulevard and 65th Avenue, Merica Learning Systems, I was stumped. Surely the initial “A” had fallen off? Then I saw the name again, on the awning over the front door. Perhaps it always was Merica, but perhaps, just perhaps, the letter fell off long ago and it was decided to make the mistake permanent. The building also contains a pizzeria poplar with the QC lunch crowd and a day care center.

“Pomonok” is a prominent name in these parts, enough so that the immediate neighborhood is sometimes called by the name, as well as a playground and a nearby housing project. It can also have a variety of spellings such as Paumanok or Pomanok, since it was a Native American name and the English alphabet was not originally used to spell it: it was an Algonquin name for Long Island. William Wallace Tooker, a 19th-century expert on the subject, thought that it meant “land of tribute.” Other translations have included “fish-shaped” and “land where there is traveling by water.” The word was favored by Walt Whitman in his works, and since Whitman was a former neighborhood resident and educator, the name has been liberally applied in the neighborhood.

From the Pomonok neighborhood page by Christina Wilkinson:

Jaynes Hill, the tallest hill in Long Island, is a short distance from Walt Whitman’s birthplace in Huntington, Suffolk County. Both the Long Island Sound and Atlantic Ocean are visible from its 400-foot summit. Though Whitman and his parents moved when he was just four, Whitman was drawn to this part of the island and wrote about it often. A passage from Leaves of Grass appears on a plaque affixed to a large boulder, deposited by a glacier, at the summit of Jaynes Hill.

The Pomonok Houses are located in 35 buildings 3, 7 and 8-stories high on 51.98-acres with 2,070 apartments housing an estimated 4,204 people. Completed June 30, 1952, the complex is bordered by 65th And 71st Avenues, Parsons and Kissena Boulevards.

Both playground and housing project stand on the grounds of the Pomonok Country Club:

The course was built by members of the Flushing Athletic Club, which began in 1886 as one of the first golf clubs on Long Island. They leased 83 acres of land along Northern Boulevard in Flushing. When their lease was set to expire in 1919, some members favored finding a new, larger site that had room for an 18-hole course. Others favored renewing the lease at the original site and gradually expanding their 9-hole course. The membership ended up splitting, with the bolting members forming the Pomonok Country Club along Kissena Boulevard in 1921.

An interesting feature that has been retained is the presence of several original vinyl directorial signs in my favorite color combination, gold and black.

The art of sign-cramming was perfected by the Department of Transportation here at Jewel Avenue, which crosses Kissena Boulevard south of the Pomonok Houses. Instead of installing a separate sign, the DOT puts both of the street’s names on the same sign, and that was carried forth to the newer one-line signs hung on traffic signal mastarms, making for an incredibly lengthy piece of metal.

Harry Van Arsdale, Jr., president of Local 3 of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers, was instrumental in the construction of the nearby Electchester Houses east of Parsons Boulevard north of Jewel Avenue/Harry Van Arsdale, Jr. Avenue one block away.

Jewel Avenue has a curious history, and I’m not sure why it wasn’t just given a number when it was laid out. Presently, west of 147th Street, it runs between 69th Road and 70th Avenue and I imagine Queens Topographical didn’t want to call a lengthy avenue “69th Drive” which it would oridinarily be.

Also, curiously, “Jewel Avenue” is the last remnant of Forest Hills’ alphabetical nomenclature system (it once was in a sequence that included Fife, Gown, Harvest, Ibis, etc. as seen on this 1908 atlas plate). When Jewel Avenue was given an eastern extension through Flushing Meadows and beyond, it retained its name, until the labor leader’s name was slapped onto Jewel Avenue signs in the 1980s.

And lastly curiously, Harry Van Arsdale, Jr.’s name on the street signs was also extended west as far as Queens Boulevard; however, it wasn’t extended along Jewel Avenue west of Flushing Meadows. In Forest Hills, 69th Road carried the Harry Van Arsdale, Jr. signs!

Kissena Boulevard ends at Parsons Boulevard and 75th Avenue (there’s something behind that, but I’ll get to it) but before that it makes another jog to the southeast, creating a traffic triangle and green space at 72nd Road. The small park is called Abe Wolfson Triangle, named for one of the founders of the Queens Historical Society at the young age of nineteen. Wolfson (1949-1971) was the organization’s first president and, as an environmental activist, also founded the Flushing Meadows Park Action Committee and fought for the cleanups of the Flushing River and Meadow Lake. Wolfson perished in October 21st at age 21 while learning to fly in a single-engine Cessna in Great Falls, MN.

Meanwhile, Flushing Meadows is again in need of a major overhaul to its parklands, bodies of water and general facilities both modern and historic.

Aguilar Avenue and the end of Kissena Boulevard

Here’s a photo from 1941 showing the curving Aguilar Avenue at 73rd Avenue, an intersection that no longer exists. Stay with me and I’ll discuss its relevance with Kissena Boulevard…

Here’s map from earlier in the century showing the south end of Kissena Boulevard, formerly Jamaica Road. As you can see, traveling south, it made a dipsy-do on the twisting Aguilar Avenue before continuing south on Parsons Boulevard, named for the horticulturist mentioned earlier. Some parts of the road were built before others, but with various interruptions, Parsons Boulevard now runs from the East River in Malba all the way south to Jamaica Boulevard in the heart of Jamiaca (it’s actually the east end of the E and J subway lines).

Over time, though, the western end of Aguilar Avenue was renamed as a southern extension of Kissena Boulevard and the east end became parts of Parsons Boulevard (in the 1941 photo we’re actually looking at Parsons) and only a short middle section bordering the Pomonok Crest Apartments remains.

The whole S-shaped road was likely the original trace, perhaps going back to Native American days. The trace likely curved to avoid a swamp or a hill.

Aguilar Avenue today, in the one-block section connecting Kissena and Parsons Boulevards. The origin of the name is a puzzler. The name resembles the Spanish word for “eagle,” and is also a relatively common Spanish surname. Perhaps there were Spanish settlers in the area in the early 20th Century.

2017: Sergey Kadinsky has likely ferreted out the origin of the name.

You do wish that some of the original names of local roads could have been retained, at least for separate street signs. 73rd Road was formerly Blackstump Road, so named because local farmers would burn down trees and mark their property by the blackened stumps.

They say good fences make good neighbors. A short section of the present 71st Avenue once carried this name. I’ve rendered each in 1960s-style Queens signs they would carry if the names still existed.

I’ve always been fascinated by the Kew Gardens Hills Apartments, a collection of buildings found between 150th Street, Kissena Boulevard, and 72nd and 75th Roads. They look like no other housing project I’ve ever encountered, with their vinyl sides made to resemble clapboard in shades of brick red and light blue. Anyone have any documentation about these buildings, their history and planning?

Kew Gardens Hills boasts some immigrants form Afghanistan, who have kept shops along Parsons Boulevard for several years; look carefully and you can see an outline map of Afghanistan on the Kouchi supermarket sign. A neighboring market has (cannily?) called his shop American Flag, perhaps to assuage the fears of neighbors.

Kissena Boulevard ends here, at Parsons Boulevard and 75th Avenue, and a section of the Kew Gardens Hills Apartments.

3/8/15