PART 1 | PART 2 | PART 3 | PART 4 | PART 5

Metropolitan Avenue is one of the lengthiest routes between Brooklyn and Queens. It was first built in 1815, give or take a year, as a toll road and was known along much of its length as the Williamsburg and Jamaica Turnpike until the mid-1800s, when it was bestowed its current name. It runs from the East River to Jamaica Avenue and along the way, marks the southern limit of Newtown Creek, and runs through Lutheran/All-Faiths and St. John’s Cemeteries, as well as Forest Park. It’s the spine of several communities — Williamsburg, Middle Village (so named because it was midway between Williamsburg and Jamaica), Forest Hills and Kew Gardens, and forms the boundary line between Ridgewood and Maspeth.

I have walked along the full lengths of many roads during the 16 years (as of 2015) spent doing Forgotten New York. I usually make two or three trips or so — it took about ten years before I was able to complete Bedford Avenue from Sheepshead Bay north to Greenpoint! It usually doesn’t take that much time; Richmond Terrace on Staten Island took two separate trips in two or three weeks.

I choose the routes I am going to walk full-lengths carefully. The most important thing is, the road has to have a lot of changes — infrastructurally most of all, because that is what I concentrate on, but also the ‘feel’ or atmosphere has to change dramatically along the way. There are a number of lengthy roads in Queens like Francis Lewis Boulevard that are mostly residential; the “Frannie Lou” looks different than its other sections only when it passes through Cunningham Park. I do not want a “sameness” in the pictures.

Unlike my other full-length street pages this time, I did it all in one burst and walked the full length of Metropolitan Avenue in one day, taking about eight hours. I am not a speed walker. My legs are short and I take short strides. Little old ladies can get ahead of me. I am also stopping a lot to take pictures. Had I decided to walk more briskly, I suppose I could have shaved an hour or two off. According to the measurement tool on Google Maps, Metropolitan Avenue is about 8.3 miles from the East River to Jamaica Avenue, so I was going one mile an hour.

My total mileage on the day was 13 miles. That’s because I had to walk through Williamsburg to get to Metropolitan and then down Jamaica Avenue to get to the Jamaica LIRR station, where I got a train to Woodside and then another one to Little Neck.

GOOGLE MAP: METROPOLITAN AVENUE

After crossing English Kills and Newtown Creek, Metropolitan Avenue continues eastbound, skirting the northern edge of Ridgewood. Some say that it forms the boundary between Ridgewood, to the south, and Maspeth, to the north. Personally, I’m getting more of a Ridgewood vibe when I’m in these parts, so I’ll go with that.

From my recent post in Brownstoner Queens:

Ridgewood, originally known as South Williamsburg, sprung up north of the reservoir constructed in 1856 to supply water to the then-city of Brooklyn in what is now known as Highland Park. Water flowed through a series of culverts through Nassau and Queens, and today the names Aqueduct Racetrack, North and South Conduit avenues and even Force Tube Avenue reflect their former presence. The reservoir was named the Ridgewood Reservoir after the Ridgewood Ponds, the culverts’ eastern source, near Wantagh in Nassau County.

When development came to South Williamsburg in the mid-to-late 1800s, residents desired their own identity and came up with the name Evergreen for the nearby Evergreens Cemetery, but the region was formally named Ridgewood in the 1910s for the then-important reservoir, which still exists but was decommissioned in the 1960s.

Until the 1910s and ’20s Ridgewood was suburban and nearly rural in some spots, with farms and sprawling country homes, but developers Paul Stier and Gustave X. Mathews made marks that survive to this day by constructing acre upon acre of handsome row houses along its streets; Mathews’ blocks, many of which are now landmarked, feature yellow bricks from the Balthazar Kreischer kilns in Staten Island.

There are actually two Linden Hill Cemeteries between Woodward, Grandview and Metropolitan Avenues and Starr and Stanhope Streets: Linden Hill Methodist, accessible from Woodward Avenue and Hart Street, and Linden Hill Jewish (Lahawith, or Ahawath, Chesed), on Metropolitan Avenue east of Starr Street. The Jewish cemetery is the final resting place of longtime NYS Senator Jacob Javits (1904-1986), while a notable permanent occupant of the Methodist cemetery is playwright and Broadway producer David Belasco (1853-1931).

This small area of Ridgewood was originally called Linden Hill, and there is a Linden Street nearby.

This is but the first of some of the large cemeteries Met Ave. encounters as it bullets east. This side of Linden Hill Cemetery is awaiting some tenants.

Four attached stone houses east of Nurge Avenue, each painted a different color.

Nurge Avenue is the only surviving street name from a small cluster of interlocking streets located north of Met Ave., east of Flushing Avenue and south of the LIRR Bushwick branch freight racks. Some have been given street numbers, while two others were named Arnold and Andrews Avenue. Other streets were named for seas: Baltic, Atlantic, Arctic, Pacific, Adriatic, resembling the pattern in Atlantic City. All this was wiped off the map during the wholesale street numbering system adopted in the 1920s.

Three of four rather large brick apartment buildings at Metropolitan and Andrews Avenues. Note that while they were likely built by the same developer, the ground floor treatments are different.

One of the only freestanding homes on this stretch of Metropolitan Avenue at 56th Street opposite Himrod Street.

A classic firehouse at Metropolitan Avenue west of Forest, Engine 291/Hook & Ladder 140, has been here since 1915.

Terrific brick and stonework, with painted seals of the City of New York. The seal depicts a Dutch sailor (left) and an Indian from a tribe in Manhattan, presumably a Canarsee or Weekquaeskeek. (This particular seal is erroneous in that the clothing of the Indian doesn’t match what a Canarsee or Weekquaeskeek would wear in the 1600s).

Even that tiny building on the corner of 56th Street has a nice share of Tudor detail. Actually it’s not that small, as it runs half the entire block of 56th Street north to 62nd Avenue.

Between Harman Street and Forest Avenue you may be in the mood for some soft-serve ice cream. I always am, and so I almost always patronize this roadside Carvel, which still has what must be close to its original signage, as well as what once were a pair of rotating ice cream cones perched above. In October 2012, Hurricane Sandy made quick work of the ice cream part of the revolving cones, but shards of it remain.

The original Carvel, opened by Tom Carvel (1906-1990) in Hartsdale, New York in Westchester County 20 miles north of NYC, closed a few years ago to make way for a retail mall — business hadn’t been good. In 1934, Carvel was aided by a breakdown of his frozen custard truck in Hartsdale: he decided to sell the contents on the spot rather than let them spoil, and began to franchise in the Forties. By the mid-1980s, at Carvel’s peak, there were 865 ice cream franchisees. Carvel, you might recall, narrated his own commercials in his trademark unpolished style from the 1960s through the 1980s.

Spot all the classic fonts on this storefront sign opposite the Carvel. I make Times Roman Bold Italic; Century Schoolbook Bold; Baskerville Bold; and either Standard or Ariel on the sanserif.

Eliot Avenue begins at Met Ave. and 60th Street and runs straight to Queens Boulevard through Mount Olivet Cemetery and past Juniper Valley Park. As the Juniper Berry, the publication of the Juniper Park Civic Association explains, Eliot Avenue was extended east past Woodhaven Boulevard only in 1938-1939 as a means for Ridgewood and Middle Village residents to have a straightforward means to get near the 1939-1940 World’s Fair. At times, Eliot Avenue was called 61st Avenue, but the Department of Traffic eventually settled on honoring Walter G. Eliot, an engineer in the Queens Topographical Bureau in the 1910s when the avenue was first laid out. Eliot Avenue in its present widened form (except through Mt. Olivet, where it remains a 2-lane road) was completed in 1939.

As a quirk of geography, in Queens 61st Avenue is found only in the neighborhood of Glen Oaks, way out east!

A group of attached brick residences at Met Ave. and 60th Lane, some of the few homes on this stretch mostly given over to 7-Elevens, Boston Markets, Walgreens and other franchisees.

Metropolitan Avenue and Fresh Pond Road is one of the major crossroads on the Ridgewood-Maspeth border. The road was actually named for a “fresh” — as opposed to salty — pond, since drained and filled in, near Mount Olivet Cemetery. The road originally extended south past the cemetery belt into Brooklyn, but the southern section was renamed Cypress Hills Street early in the 20th Century.

For decades, Fresh Pond Road rated a Long Island Rail Road station, but it closed for lack of ridership and outdated equipment in March of 1998. The concrete fence is sufficiently high to prevent me poking the camera enough to get a good shot of the former station, but you can see the pedestrian bridge in the rear that allowed passage over the tracks. The entrance on Met Ave. was fairly well hidden even when the station was open.

Admiral Avenue runs 3 blocks along the railroad from Met Ave. to 65th Lane. In 2003 it was sub-named for a local resident murdered in the 9/11/01 terrorist attacks. The avenue is so obscure, the Google Street View truck hasn’t been there!

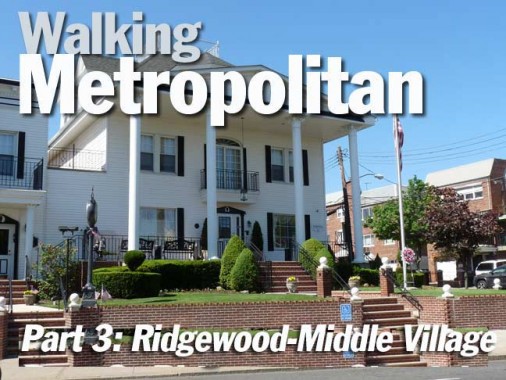

The most attractive building on this stretch of Met Ave, is the Hess-Miller Funeral Home at 65th Street. Its location is no coincidence, as All-Faiths (Lutheran) Cemetery is a block to the east. (Middle Village may even be called The City of the Dead.)

This building dates from 1902 and was originally the summer home of a local politician. In 1920, John Miller purchased the home and established his funeral parlor here. When Arthur Hess partnered with him in the 1940′s, it then became the Hess-Miller Funeral Home. It is still in business under the same name, although it is no longer owned by either family.

Even though Mount Olivet Crescent meets Met Ave. here, this isn’t Mount Olivet Cemetery. Instead this is All-Faiths, originally Lutheran Cemetery, instituted in 1852 when 225 acres of plains in Queens were purchased by Reverend Frederick William Geissenhainer, the pastor of St. Paul’s German Lutheran Church in Manhattan. That same year, new burials were prohibited in Manhattan, and Protestant, Catholic and Jewish congregations sought new land in the then-wild open spaces of Queens.

Many of the victims of the General Slocum tragedy were laid to rest here. A monument dedicated in their honor at which an annual memorial ceremony takes place is found within the confines of the cemetery’s southern portion.

Metropolitan Avenue runs straight through All-Faiths and, as we’ll see, one other huge cemetery.

Metropolitan Avenue gains a couple of lanes when it passes the Metro Mall between 65th Place and the last stop of the M train. According to the Times Newsweekly, the mall, formerly known as Rentar Plaza, stands on land formerly owned by Western Electric, which had purchased the parcel in 1929 from the Turner-Armour Company, which made public telephone booths. Western Electric continued their manufacture until the mid-1960s. After that, United Merchants and Manufacturers Inc. acquired the property and built a Robert Hall clothing store there which it shared with Macy’s and a training office for the NYS Department of Corrections. Robert Hall went bankrupt, and Rentar Plaza was built on the property in the 1970s.

The MTA subway makes its only stand in Middle Village here on Met Ave. just east of the mall. The M train has seen many routes in its several decades of existence — it once ran on the West End line, currently serving the D train, all the way to Coney Island, and also provided local service with the R train on the 4th Avenue line in Brooklyn. Since 2010 it is the only subway route that begins and ends its route in Queens, beginning at the 71st/Continental Avenue station on the Queens Boulevard line, running down the 6th Avenue line in Manhattan, and then switching to the Williamsburg Bridge and traveling with the J on the Broadway Brooklyn el. (On weekends, the M is confined to a route between Met Ave. and Essex Street in Manhattan.)

East of the station Met Ave. runs through All-Faiths Cemetery. I got a close-up view of the stone-blocked cemetery office building, then entered on a roadway on the south side of the avenue (paved with uneven Belgian blocks, it’s hard to walk especially after you have already walked several miles from the East River.

I found an interment with the unlikely name of Salome Martian and found a handsome Chinese memorial structure.

Looking west on Metropolitan Avenue, #1 World Trade Center looms above all.

Christ the King Regional High School was instituted by the Catholic Diocese of Brooklyn (which also included Queens) in 1962. Classes were held at Mater Christi High School in Astoria until the new building seen here in Middle Village was opened in April 1964. The school is best known for its basketball program, which has produced NBA and WNBA stars such as Lamar Odom, Jayson Williams, Chamique Holdsclaw, Sue Bird and Tina Charles.

At the NE corner of Met Ave. and 69th Street, with All-Faiths Cemetery still across the street, we come to one of my favorite buildings in these parts, the Frank T. Lang Building. It was built by Lang, a mausoleum and monument manufacturer, in 1904. During renovations in the 1990s, a Bohack gasoline station sign was revealed there; Bohack made a foray into auto parts distribution in the early 20th Century. Lang went out of business in 1946 and the building has seen mixed use since then, with an auto body repair shop on the ground floor for the past several years. My favorite feature is the pair of laughing cats that guard the roofline on the chamfered edge of the building.

East of 69th Street there is a brief interruption in All-Faiths Cemetery on the south side of Metropolitan. Currently the space is filled by a Radio Shack (reports of the chain’s death apparently have been premature) and by an Arby’s, which, on one of the rocks guarding a driveway, there is an etching depicting a lengthy, two-story restaurant called Niederstein’s which formerly occupied the space.

Niederstein’s served typical German fare and in recent years catered mainly to funeral and wedding parties as well as loyal locals. There was no joy in “Midville” when the restaurant closed in February of 2005 and was sold to a fast food franchisee. Arby’s eventually razed the building. Over the years its interior and exterior had been altered to such a degree that it was deemed unworthy of protection by the Landmarks Preservation Commission.

One remnant of Niederstein’s that remained for quite a few ears after it closed in 2005 was its old parking lot at 70th Street which was marked by an illuminated sign. On today’s walk I found it had finally been replaced with a 2015-appropriate multifamily house.

At 71st Street we’re still across from All-Faiths Cemetery and rather appropriately here is New York City’s one remaining taxidermist. I haven’t been by when he is open but FNY did a feature on this place, nonetheless, in April 2015.

A couple of blocks east, at Pleasantview Street (which sits in the place of 73rd Street, and could be named that, but I’m always happy to find a ‘named’ street in Queens), we find the Juniper-Elbow Company building, which still has a working illuminated clock. I originally though this was a pasta factory, but as it happens, Juniper-Elbow actually makes the curved pipes used in furnaces and for other uses. The company has been in business since 1928 and makes a general array of watertight metal products.

This newish Tudor building at 72-35 is a condo development, Metrose Gardens. The building is much longer than it is wide, extending most of the way back to 66th Drive.

Metropolitan Avenue enters Middle Village’s “downtown” and business stretch between 73rd Place and 80th Street and, a few years ago, it was tricked out with a set of retro versions of Type F lampposts. In a former life, this style was shorter and thinner and used mainly on side streets, but the DOT put them on steroids and now they have muscles. In one case, a Bishop Crook mast was placed on a Type F base, but that’s an outlier.

Painted ads for Coca-Cola are easy to recognize — the company logo has not changed in over 90 years. This ad appears on a building on the south side of Met Ave. east of 73rd Place in a driveway between 2 buildings that look very much the same; but apparently whoever paid for the ad thought it would be exposed a lot better than it is.

Above the Coca-Cola ad, I can make out a sign for a local drugstore that has its name on the first line, then the slogan “the finest drugstore in the village.” I could make it out better if the sun wasn’t directly on it. Can anyone make it out?

Community United Methodist Church, 75-27 Metropolitan Avenue, is the first church I encountered on Met Ave. since I entered Queens. As often happens, information on the church history is sketchy, as far as churches are concerned, infrastructure and architecture is considered secondary to mission and is not mentioned in many cases.

The painted ad abuts a pair of attached “brownstone” or “beigestone” buildings atypical for Met Ave. Could the “dance club” named on the awning be the same as the dancehall/bowling alley mentioned on the ad?

It gets a little confusing in these parts. Rosa’s Pizza, Met Ave. and 78th Street, gets good Yelp reviews for its fare, while a similarly named venue, Rosa Pizza, without the apostrophe s at 55-26 69th Street in Maspeth, also rates high. But my favorite pizzeria around here is neither of those: it’s Rosa’s Pizza at 62-65 Fresh Pond Road just south of Met Ave.!

I do have a feeling that the Met Ave. and Fresh Pond road Rosa’s share an owner.

East of 78th Street, freestanding private homes again appear on Metropolitan Avenue. Without a doubt the best maintained of these is at 78-16 Met Ave., which has recently been given a renovation that has restored original elements — or they may always have been retained. Whichever is the case, the original door moldings seem to be there as well as the original roof corbelling and pediment. Extraordinary — magical…

Another bank of attached brick houses on the south side of Met Ave. east of 78th Street, The end buildings have round edges, while the center buildings have “polygonal” or dual-angled, bay windows, convenient for looking east and west on the avenue.

Closeup of the “reverse-scrolled” Type F bracket. Note the 3 tiny florets that appear on each side. While bishop crooks feature ‘regular’ scrolling, e.g. the lamp curves downward, in Type Fs, the ironwork curves upward — hence, “in reverse.” In retro Type F’s the photocell, the unit that regulates when the lamp comes on in the evening, is perched on the finial.

We’ve seen blissful simplicity on Met Ave. — here’s what happens when Architects Run Wild, with a double porch, Tuscan columns, a pair of human heads on the third floor, eagles on the roofline. The awnings bear the mysterious initials “J.P.” Any ideas?

Another puzzler would seem to be the Uvarara Wine Bar and Ristorante at 79-28 Met Ave., which features intricately carved stonework and a clock and the word “Artistic” on one of the corners. But I think we can safely assume this was a stonecutter servicing St. John’s Cemetery, which is a block away.

80th Street, formerly Dry Harbor Road, is considered the east end of Middle Village. (A piece of Dry Harbor Road, so named because early settlers thought the view of it from surrounding hills made the plains look like a sea) remains a liitle north of here from Furmanville Avenue and Woodhaven Boulevard).

Met Ave. runs through another vast cemetery, St. John’s Cemetery, instituted in 1883 as part of the Diocese of Brooklyn after purchase from a farmer. Additional sections were added in 1933 and 1947, bringing the total acreage to the current area bordered by 80th Street, Cooper Avenue, Furmanville Avenue and Woodhaven Boulevard. Since Met Ave. was here first, the cemetery was built around it. The vast region was once part of the Hempstead Swamp.

Over the years St. John’s has gained a reputation as the last resting place for members of the Mob. Indeed, mob leaders Joe Colombo, Carmine Galante, Joseph Gambino, Vito Genovese, Lucky Luciano, Joseph Profaci and perhaps the best-known mobster in history, John Gotti, are all interred here. However St. John’s has attracted “customers” from all walks in life, and Governor Mario Cuomo, Mayor John Hylan, and U.S. Representative Geraldine Ferraro lay at rest here, as well as bodybuilder Charles Atlas and avant-garde photographer Robert Mapplethorpe.

The road goes on forever. Or at least seems to — Metropolitan Avenue runs for about one mile through the cemetery. It’s not easy walking, since there are no sidewalks on either side, only paths beaten through the grass. I’d think the cemetery and the Department of Transportation do not agree on who should provide the sidewalks.

Or, perhaps, the DOT assumes no one will walk this route except shambling crazy men with cameras.

In Part 4: into Forest Hills

PART 1 | PART 2 | PART 3 | PART 4 | PART 5

9/20/15