I decided to take my latest voyage of discovery in Flushing in October 2015, when its intrinsic oderifousness is tamped down just a little. My idea started when I did an item on an obscure lane, Birds Alley, that ceased to be a mapped street decades ago, but its path is preserved by a driveway and by Google Street View, which still duly names it. Thus, I decided to revisit some of Flushing’s labyrinthine jumble of streets — the neighborhood was first settled in the 1630s and many of the roads were built for horses and wagons, not automobiles — and see if there were any surprises there.

There are a few, but one of the things you discover when you revisit a neighborhood with a keener eye, you notice patterns and “designs” you may have missed first, and details that has escaped you years ago stand out of the pack, plain as day, and you have no idea why you didn’t see them in the first place.

I began at a Q12 bus stop (the route connects Flushing and Little Neck) at Roosevelt Avenue and Bowne Street, then followed the route shown toward Flushing’s industrial corridor that nonetheless has some residential and historic buildings sprinkled here and there.

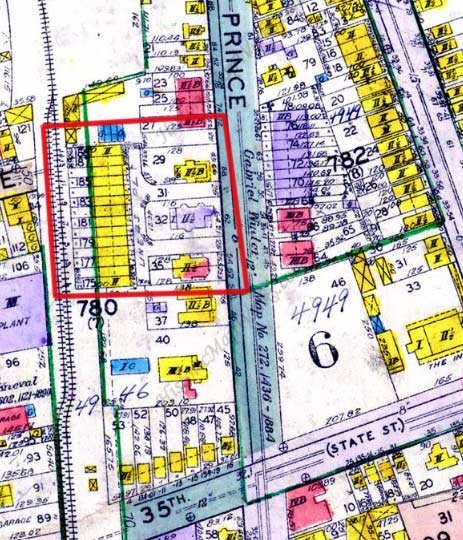

I return to the Queens map of 1909 again and again, because that was the period in which Queens was still largely rural but its street grid was recognizably today’s, especially in long-settled regions like Flushing. The street layout shown here largely persists today, but most of the names have been changed; Lawrence Avenue is now College Point Boulevard, Myrtle Avenue is 32nd Avenue, State Street is 35th Avenue, Bridge Street is Northern Boulevard and so forth. Some of the old names persist today, such as Farrington Street — an old Flushing name; a gas station that originally served as a horseshoer and wagon repair run by the Farrington family is still in existence on 15th Avenue in College Point. Linden Avenue is now Linden Place. On the map I have circled a small enclave on what is now Prince Street — I’ll return to that shortly.

At the end of Part 1 I had left off at College Point and Northern Boulevards. Northern Blvd. crosses the Flushing River over the last in a succession of bridges going back to the 19th Century. A pair of service roads connect it to College Point Boulevard.

On the, well, “northern” Northern Boulevard service road, facing west, is a painted ad showing the traditional logo of Chevrolet, the auto manufacturers, between Collins Place and Prince Street. Chevrolet has used this cross with slanted edges, which it calls the “bowtie,” since 1913 (the company was founded in 1911).

There are a variety of stories about how and why the logo was designed this way. The company’s website proposes four different ways: 1) Chevrolet co-founder Billy Durant saw the design and liked it while he was vacationing in Paris, France and saw it as a pattern on hotel wallpaper. 2) Durant’s daughter, Margery, says she saw him doodling it on a sheet of paper. 3) It copies the Swiss flag, a red square (sometimes a rectangle) with a central white cross. Louis Chevrolet was a Swiss. 4) Durant copied the logo from the Southern Compressed Coal Co. logo for its brand Coalettes, which ran magazine and newspaper ads in 1911, the same year Chevrolet was founded. This seems to be the most believable theory, as hard evidence for it exists.

Interestingly, Chevrolet did not begin printing the logo itself without the word “Chevrolet” in it until 1985.

Collins Place and Northern Boulevard. Prominent in the neighborhood are tile, glass and lumber wholesalers as well as cement manufacturers and dealers. Flushing Blueprint, which has offered digital printing and copying services for several years, has been in business since 1924.

Queens Lumber, another longtime College Point Blvd. wholesaler, was owned by Queens Assemblyman Jimmy Meng, who was arrested and subsequently convicted of federal bribery charges. His daughter Grace won his old seat in the 22nd Assembly in 2008 and was subsequently elected to the US House of Representatives in 2012.

The Flushing River side of College Point Boulevard is lined with concrete plants. On Time Ready Mix proclaims, on its stacks and on other signs, that it is “open to the public.” I strongly suspect that I shuffled onto the premises and started shooting photos, I would be quickly ushered out of there.

In the past, coal and ice yards lined the creek.

This very old, crumbling concrete building and wall protect electric equipment with warnings about high voltage. I’m stumped by this, anyone know if this is connected to the MTA in any way?

An insider who knows me writes:

The crumbling concrete building with the high voltage warning signs on College Pt Blvd is actually a Con Ed substation. It steps down high voltage from transmission lines to a lower, usable voltage for businesses and customers in that area. About 10 years ago, or so, tragedy struck behind that fence. I was working in the area and remember it well. A Con Ed worker was sitting in his truck, having his lunch. Next, door, at Tile World [see below], used to be racks of tiles next to the fence. A worker loading tiles with a forklift, accidentally pushed the rack over, and on top of the Con Ed truck, crushing it, and the worker inside.

The nearest MTA substation, however, is near the north east corner of College Pt Blvd and Roosevelt Avenue. It steps down voltage from Con Ed, and then converts it to DC with a rectifier, for third-rail traction power for the 7 train. Third rail powered railroads and subways need one every couple miles, as DC voltage does not transmit as far as AC voltage (without very significant expense, at least.)

I like that nearby Tile World uses the now-rarely seen Souvenir font on its multicolored sign, but Yelp reviews for the floor and wall tile dealer say customer service leaves something to be desired.

I turned east on 34th Avenue but not before taking a look at the stacks of the Willets Point Asphalt Company, which its website says has been in business for what is now over 85 years.

Oddly, the plant, as well as the neighborhood referred to as Willets Point, is nowhere near the actual point in far northeast Queens where Fort Totten is actually located. Charles Willets, one of many plant nursery owners in Flushing, aquired land in northeast Queens which was sold to the US Government to build Fort Totten there in 1857.

This area is known as “Willets Point” because of the presence of Willets Point Boulevard, which was originally mapped in the 1920s to run continuously from Roosevelt Avenue all the way to Fort Totten. However, when the Whitestone Parkway, now Whitestone Expressway, was built in the 1930s, it assumed the boulevard’s route and it was built in two separate pieces, one running a few blocks between Roosevelt Ave. and Northern Boulevard and home to the auto repair and wholesale parts shops that the city has tried to evict for decades for shiny new housing, and the longer eastern section, which runs from Union Street to the Cross Island Parkway.

The confusion arose because of the new Willets Point Boulevard el station opened in 1925. Train operators referred to it as simply “Willets Point” and that abbreviation stuck in public parlance.

A&G Marble, on 34th Avenue, formerly Pine Street, features samples of its product on the exterior fence.

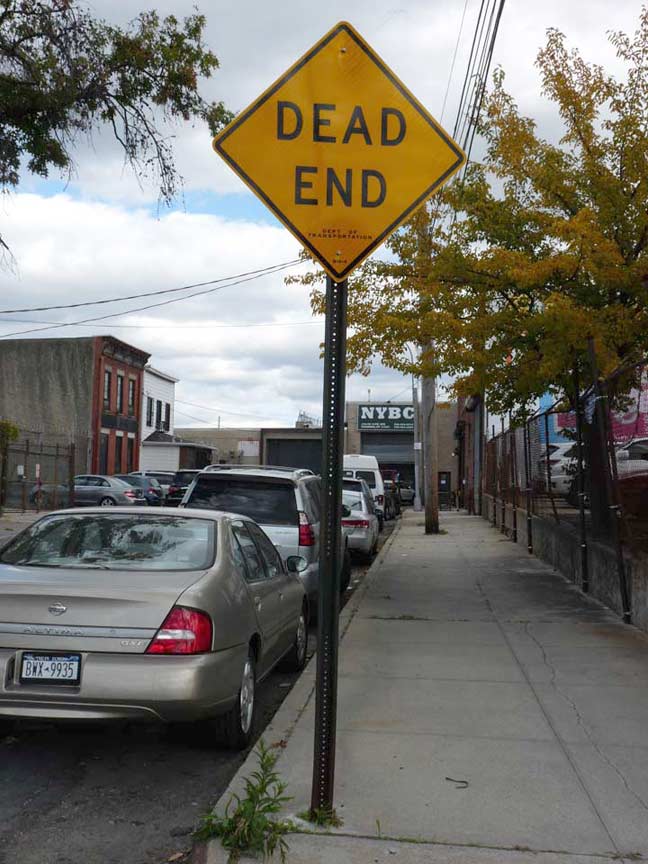

If you look at the 1909 map above, Pine Street (34th avenue) used to reach a dead end at the Whitestone Branch of the LIRR. It still dead ends today but there are surprises to be found just ahead, even though the railroad stopped running in 1932 and was demolished soon after that with almost no trace.

Brick and wood frame dwellings, looking as they have for decades, appear on the north side of the street. However, I don’t think they are still used as residences and may have something to do with the building at the very end of the road…

… which is the home of the New York Badminton Center. Pictures of Malaysian champion Lee Chong Wei and Lin “Super” Dan (China) can be seen at the door. The game is similar to tennis, but is played with specialized racquets and, in place of a tennis ball, a conical projectile called a shuttlecock, as well as a number of other differences. Badminton originated in India during the British colonial period in the mid-1800s and is today competed around the world.

You exit the area by heading south on Collins Place, then east on 35th Avenue. On Collins is a huge, imposing bunker-like concrete behemoth, called an “ice plant” on a 1928 map of the area, now home to the Harvy Supply Co.

So this is where all those shiny metal fences on all the Queens Crap going up all over the borough comes from: New York Eastern Metal on 35th Avenue between Collins Place and Prince Street.

I didn’t walk on Linden Place (much) today, but that road is the epicenter of bad architecture in Queens.

Next door on 35th Avenue are more tile, glass and building front suppliers…

… and for a change of pace, a poultry slaughterhouses. The squawkings of unsuspecting feathered friends were heard within.

The southwest corner of 35th Avenue and Prince Street showcases a rare western Flushing survivor: a 3-story frame house with its front porch and dormer windows intact. A couple of houses down the block on Prince are of similar vintage but have had additions on the front that mask their true age.

A Deco-ish apartment building, also unusual for these parts, remains at the southeast corner. It seems to predate the era, though. The name of the building over the front door on 35th is “The State” — appropriate, because 35th Avenue was once State Street.

Walking north on Prince, there’s a low brick building midway between 35th and 33rd Avenues, occupied by a wholesale truck parts distributor…

…surrounded on both streets by narrow alleyways, both marked “Linnaeus Place.”

Both of these alleys lead to another perpendicular alley lined with what were once brick-faced buildings that are now covered from head to foot with aluminum siding.

Not only that, but that perpendicular alley also has a pair of dead-ends at each end of it!

A view of the alley on the north side of the truck parts show, looking both east and west.

The entire complex is shown here on this 1928 map. The entire complex, called Linnaeus Place, looks like a Greek letter Pi turned sideways. Real-estate listings (which are dubious, I admit) say the attached buildings date back to 1901, but that seems about right.

The entire complex is shown here on this 1928 map. The entire complex, called Linnaeus Place, looks like a Greek letter Pi turned sideways. Real-estate listings (which are dubious, I admit) say the attached buildings date back to 1901, but that seems about right.

(Left) Linneaus Place has changed a bit since I first photographed it in 1999. It was in decrepit condition in those days, with a barely paved roadbed and no sewers!

As for the odd name, it’s a relic of the days when the Prince family owned a retail plant nursery here featuring flowering plants and fruit trees.

Prince’s son William Prince Jr. established a new plant business north of Northern Boulevard (then called Broadway) in 1793; it would later be united with the original gardens and named the “Linnean Gardens.” Swedish naturalist Carolus Linnaeus had established the system of biological naming known as “binomial nomenclature” consisting of a Latin genus name followed by a descriptive term: for example, Homo sapiens means ‘wise man.’

Today only the street names bear witness to the plant nurseries’ former presence: the Waldheim development’s Ash, Beech, Cherry, etc. Avenues; Prince Street; and an odd, Pi-shaped little alley on Prince between 33rd and 35th Avenues, Linneaus Place, hidden among the auto parts stores and lumberyards that now dominate the area.

Facing Linnaeus Place across Prince Street are a pair of stolid multifamily buildings, likely from the same era (1900-1905)

Returning to 35th Avenue, this is the rear end of the RKO Keith’s Theater at Northern Boulevard and Main Street. RKO Keith’s has lay empty at the head of Main Street at Northern for over 30 years, resisting all attempts to restore or renovate it; indeed, a previous owner, developer Tommy Huang, gutted much of the lobby. A recent plan to make it a shopping mall, while retaining its grandiose lobby, appears to be stalled. It was built by prolific theater architect Thomas Lamb in 1928. Vivid accounts of what this great landmark once looked like, and what became of it, can be found at cinematreasures. With other long-moribund theatres like the Loew’s Paradise in the Bronx, St. George in Staten Island and Loew’s Kings in Flatbush (the latter two now hosting big names in concert) will the Keith’s moment in the sun ever come?

Turning south on Linden Place, you can see the back edge of Flushing Town Hall, now a neighborhood cultural center and concert hall (

The back of Town Hall can be seen from Carlton Place. Take another look at the 1909 map at the top of the page and at the bottom of the map, between Linden and Leavitt, you can see that Carlton Place, and its set of compact individual homes, was there even then.

One of these things is not like the others. Both sides of Carlton Place are lined with those modest individual homes, except for one large log of Queens Crap. There’s nothing to legally prevent noncontextual buildings like this to rise on Flushing’s streets.

Heading north along curving Leavitt Street to the irregularly-shaped Leavitt Park, which contains a modest, well-preserved frame house . More on that in a bit.

Leaavitt Street stands out among Flushing streets in that it runs on a curve from Northern Boulevard north to 32nd Avenue. A clue for why this is may be found in the street’s former name, Spring Lane (seen on this 1928 map plate). The street may follow the route of a former creek or spring that has been beneath the grid since the colonial era.

As for the house, which is marked with a New York City Economic Development Corporation-sponsored sign, it was the residence of Lewis Latimer, engineer and inventor of the lightbulb filament.

Latimer (1848-1928)was born in Massachusetts to parents formerly held in slavery in Virginia. He enlisted in the U.S. Navy in 1864 and upon his release, answered an ad for an office assistant from the patent law firm of Crosby and Gould, ascended to head draftsman, and discovered he had a knack for invention.

While still at Crosby and Gould, Latimer assisted Alexander Graham Bell, providing the drawings for Bell’s patent application for the telephone; after leaving the law firm, Latimer joined the U.S. Electric Lighting Co, a chief rival of Thomas Edison. There he would produce a long-lasting carbon filament that was a major improvement on Edison’s 1878 electric lightbulb; Edison’s filaments, which used bamboo filaments, burned out quickly, making early bulbs impractical. Latimer published “Incandescent Electric Lighting, A Practical Description of the Edison System,” an early electric lighting guidebook, and went on to develop arc lamps and cooling and disinfecting devices. Latimer also developed the first threaded lightbulb socket and assisted in the installation of New York City’s first electric streetlamps, among many other inventions.

After residing in Brooklyn for a number of years, Latimer moved his family to a small frame house on Holly Avenue in Flushing, where he corresponded with Frederick Douglass and Booker T. Washington.

By 1995, the small house, which was in a deteriorating state, was declared a landmark and was later restored to its original condition and moved to a new location at 137th and Leavitt Streets, across the street from the public Latimer Houses, which were named for the inventor. Latimer’s granddaughter, Winifred L. Norman, Ph. D, assisted in converting his home into a museum.

To close out my Deep Flushing walk I went south back to the Q12 bus along Union Street, jammed with signage in Korean and Chinese. The signage is interrupted by the Macedonian African Methodist Episcopal Church, which has been on Union Street and 38th Avenue since 1837, in its original building and another constructed from 1931-1932 that largely resembles the original.

While African-Americans were being pushed uptown in Manhattan the late 1800s and early 1900s, African-Americans were being removed altogether from the downtown Flushing area in the mid- to late-1940s. The officials of government identified their community as a slum and proceeded to implement a plan designed by Commisioner of Parks, Robert Moses, to build a parking lot and bus station. Not only homes, but the little red schoolhouse built in 1861 by the Flushing Female Association, despite its landmark status, fell to the wrecking balls. The new arrivals to the suburbs needed convenient parking for their shopping expeditions so a viable community was displaced for a parking lot. A way of life was destroyed as members of the African-American community were scattered, leaving only their church as a reminder of their former existence in the area.

The church was determined to maintain its presence on the original site, and with the help of the newly assigned pastor, the Rev. G. Grant Crumpley, this was accomplished despite overwhelming odds. Rev. Crumpley was able to acquire from the City the adjacent lot and the church proceeded to build the Youth Building complete with chapel. Surrounded by a city parking lot, Macedonia continues to stand in downtown Flushing on or near the original parcel of land purchased by “Trustees and members” in 1811. NYC American Guild of Organists

10/24/15

7 comments

Birds ( Byrds ) Alley might seem abandoned, but don’t be surprised if the street was illegally annexed by the businesses that occupy it. The present tenant might not be the one who did it, and not have any idea his lot is a legal street. i saw a portion of a street in Whitestone that still showed as a city street, but was considered private by a business. who’s right? Was the map not changed or squatters?

And the building on College Pt Blvd is a Con ed substation, not MTA

That Art Deco-ish 4 story walk up you pictured is really a treasure find…The State…

Just an FYI. The link to her Wikipedia page states that Grace Meng did not succeed her father. Ellen Young succeeded him. She actually beat Young in the election after the election to succeed Jimmy Meng.

“His daughter Grace won his old seat in the 22nd Assembly in 2008 and was subsequently elected to the US House of Representatives in 2012.”

Nowhere do I say she immediately succeeded him.

Lewis Latimer was born in the city of Chelsea, Massachusetts. His father George was part of a historic state legal case that allowed for the freedom of slaves living in Massachusetts so long as they paid restitution to their former owners. This was case was part of a larger growing sentiment against slavery, and helped lead to the infamous warnings to freed blacks in Boston posters that are shown in most history textbooks.

Dr. Latimer passed away in 2014 at the age of 99.

Latimer’s legacy is kept alive in his hometown by the Lewis Latimer Society which works to help mentor city kids at risk.

Are you claiming here that Lewis Latimer died in 2014? Please checks your dates more carefully.

Does anyone have a picture of the house that was in the middle of linneaus place.? That would be in the 50s or 60s possibly the early 70s