I found myself once again in Port Richmond midweek in December 2016, the subject of a number of FNY forays over the years. The story has been told here many times, but I was well familiar with the area from my youth, when my parents and I would occasionally tale the S53 bus (then known as the R7) over the new Verrazano Bridge. Occasionally, we’d wind up in Clove Lakes Park, where in 1965 I got a rare whupping from the old man when I decided to wander around the park by myself at age 8 and got lost (an incident that sort of set the tone for all my subsequent ambulations: walking around by oneself, with or without a camera, is a form of subtle subversion).

Sometimes, though, we would take the bus all the way to its terminal at Richmond Terrace and Port Richmond Avenue, which was known in the 60s at plain old Richmond Avenue; half of all important roads in Staten Island are known by the county name, Richmond. I remember one particular occasion in 1966, when I was nine. We were walking around and even then, I remarked to myself how rundown and slummy it appeared. That’s a strong word, but Port Richmond, even by then, gave the impression of a region that had seen its better days. I have amended that opinion somewhat since that tender age, but the opening of the Staten Island Mall in the 1970s only speeded its ongoing decline.

Armed with my handy dandy guide, Staten Island Walking Tours by the Preservation League of Staten Island, I set out to record that part of Port Richmond that I’d ignored on previous FNY forays here, and also lit off down Castleton Avenue, the main drag of New Brighton and West New Brighton (Staten Island has no Brighton, as its Brighton neighborhoods are named for the original in England). Since Walking Tours was published in 1986, many of the neighborhoods it covers have utterly changed, most not for the better, but Port Richmond remains mostly preserved. So far, of course, the Landmarks Preservation Commission has ignored it.

By the way, folks, there are 263 photos in this particular set. I didn’t use all of them, but enough so this will be a multipart series. To move things along, I’ll do some midweek feature posts just to keep things moving along.

I’ve already covered some of this material before in my 2014 Port Richmond page, but I’ll try to provide some additional info a bit more succinctly here.

GOOGLE MAP: PORT RICHMOND and CASTLETON AVENUE

On previous visits to Port Richmond I’ve always been fascinated with this rusted old tug, the Philip T. Feeney, that has been tied up at the end of Port Richmond at the Kill Van Kull for a quarter century. Even though there’s not much to say about the old hulk, I devoted an FNY page to it, and on this walk I snapped five more photos of it from different angles, enough for my archive that I hope will be donated to a library and displayed online after I shuffle off.

Relics and hulks cling to the corner of Port Richmond Avenue and Richmond Terrace like barnacles. This is the former Staten Island National Bank, still with its former burglar alarm on the chamfered corner. It’s mansard roof and dormer windows mark it from the 1870s; that was when French Second Empire architecture, with slanted roofs and dormer windows, was the rage. The building has served some time as a church, but seems to be abandoned these days. The building was extended along Port Richmond Avenue in 1909, employing a Classical Revival style that’s not a match for the original building on the corner.

Abandonment can preserve some original elements. That’s what happened here with the night depository slot. As we’ll see there are some curious bits along Port Richmond Avenue that look very old, but actually are not!

‘Cause when love is gone, there’s always justice

And when justice is gone, there’s always force

And when force is gone, there’s always Mom. –Laurie Anderson, “O Superman”

And there’s always Mom’s Liquors, on Richmond Terrace, one of the few businesses in the immediate area still going strong. As is its 1940s-vintage sidewalk sign. Its red neon still lights up, even during the day. NY Neon claims it for 1935.

In addition, you can still make out the words “To Bayonne” on that large metal arrow. It pointed the way yo the Port Richmond-Bergen Point, NJ ferry. While regular service ended in 1931, sporadic service continued until 1961. If NYC has gotten rid of plenty of transportation like elevated trains and streetcars, it’s also dumped plenty of ferry service.

The twin peaks of the Empire Theater are immediately recognizable on Richmond Terrace. Designed by Port Richmonder James Whitford, the theater opened in 1917 and closed in 1978. Cinematreasures has a photo of the Empire in its classic era. The building became the longtime home of Farrell Lumber (itself founded in 1888) before it, too, closed in 2009. A storefront church occupies it of late.

Robert and Donald Farrell were the last owners of Farrell Lumber, and they are remembered on a street sign.

The Walking Tours book describes this pitch-roofed house set back from the north side of Richmond Terrace next to an auto body shop as the George W. Jewett Stables, which were next to his mansion, which was torn down long ago. Jewett was the youngest member of the John Jewett and Sons White Lead Company; a lengthy Port Richmond Avenue was named for the family. I dedicated a FNY page to it, complete with a very bad pun in the title card.

Faber Park and Pool

Faber Park, Richmond Terrace and Main Street, features a view of the Bayonne Bridge as do many locales in the neighborhood. This shot, from December 2016, features a unique view, since it shows both road decks during an initiative to replace the old road deck (155 feet above the Kill Van Kull) with a higher one (215 feet) to allow large ships to pass safely under the bridge, which was opened in 1932. Once the new deck is completed in 2019, the old one will be removed. In 2017 the walkway is closed, but I crossed it in 2012. A new walkway will open when the project is done.

Eberhard Faber (1822-1879), the scion of a Bavarian pencil producing family, arrived in the USA from Germany in 1848, and after his first USA pencil factory burned down in 1861, relocated to Greenpoint in 1872. His son Eberhard II (he had changed his name from John) took over the company, which remained in Greenpoint until 1956, when it decamped to Wilkes-Barre, PA.

Faber claims to be the first pencil company to manufacture pencils with erasers; in Europe pencils still don’t feature erasers, since the theory is that children will be more careful if they can’t erase!

An entire landmarked district in Greenpoint features Faber pencil factories, and the Faber family settled in Port Richmond, Staten Island where a street and public pool are named for them. The land for the park was acquired in 1905 by Department of Water Supply, Gas and Electricity from Charles and Emma Griffith, who had acquired the property from Anna Faber. Plans for a lighting plant never came to, ah, light and NYC Parks took over in 1928.

Faber Pool and the park recreation building opened in 1932, same year as the Bayonne Bridge, and the pool was expanded in 1941. At the time of its construction it was the largest recreational pool in Staten Island.

Faber Street itself contains some notable architecture, including another Second Empire Classic on the corner of Richmond Terrace, and another building with a cupola allowing residents to look out over Kill Van Kull. These blocks deserve Landmarks protection.

The Griffith Block, constructed in 1875 for shoe manufacturer Charles Griffith, still holds down the SE corner of Port Richmond avenue and Richmond Terrace. Griffith also owned the land on which Faber Park is now situated. As period woodcuts show, the top two floors still look much as they did in the 1870s, but the bottom has been thoroughly blandified for 1970s sensibilities. A plaque on the building indicates that the now-demolished St. James Hotel, constructed in 1820, was the spot where Aaron Burr, the USA’s third Vice-President and assassin of Alexander Hamilton, passed away in 1836. The hotel was demolished about 1945.

Not-so-old painted ads: This pair can still be found on the eastern side of Port Richmond Ave. between Church Street and Richmond Terrace, and the look for all the world like ancient ads from the 1880-1920 period, but I have to say that they are leftover props from the Boardwalk Empire TV show, which shot scenes in Staten Island in Port Richmond, Richmondtown and other locations in the early to mid 2010s. But if you don’t say anything about their not being “real,” then I won’t!

This sidewalk sign for Wexler’s Hardware is, however, the real thing. Wexler’s has since moved down the block to 97 Port Richmond Avenue. There had been an additional ancient sign for Toscana Food Market on the same building, but it’s long gone.

The present Greek Revival Staten Island Reformed Church was constructed in 1844 and replaced two earlier churches on this site — the first one was chartered as early as 1696.

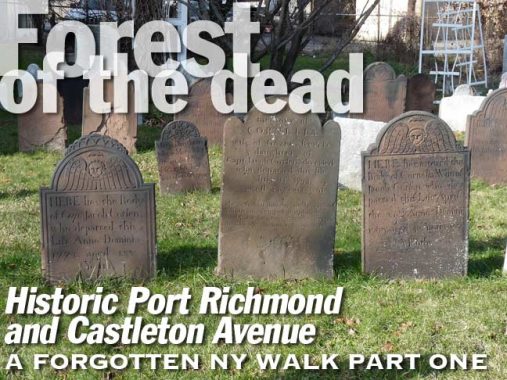

The church’s congregation is the oldest in Staten Island and its first church building was erected on this site in 1715. The present church is the congregation’s third; it is the oldest church building on the North Shore and one of the oldest churches on Staten Island.The church’s graveyard is the oldest non-private cemetery in Staten Island. NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission Report

What concerns me here most of all is the cemetery next to the church, which actually predates the church. According to some historians, the “Burying Ground” started out as a private cemetery of the Corson family, which owned much of the Port Richmond in the 1690s.

Not only are there dozens of tombstones from the 18th Century in here, there’s also a vintage New York State historic plaque from 1932. In 2013 I did a FNY series on existing and former NYS historic plaques in NYC.

The sun was at just the right angle for me to get some very good shots of the remaining brownstone tomb markers. They hold up much better to the effects of rain, wind and pollution than do their later marble and limestone cousins.

The Van Pelt family is represented on the Staten Island map with a major avenue in Mariners Harbor. This is a particularly old marker from 1749. The stone bears the early 18th Century winged skull motif.

A member of the Corson family in a latterday brownstone marker from 1821. There is a Corson Avenue in New Brighton, west of the Manhattan ferry.

A 1771 stone form the Cruser, or Kruse, family from 1771. The historic Cruser-Pelton House still stands at Richmond Terrace and Pelton Avenue.

A quintet of stones dating between 1761 and 1822 for the Linde, Mersereau and Corsen families. While the lettering on modern tombstones is mass-produced, skilled stonecarvers did the script lettering on these stones. In the rear on the right, check out the intricate design used to spell out “SACRED” and the deceased’s name CLOSHA. By this time death’s heads and skulls were still used on tombstones but weren’t as severe as they were on stones from the 1680s through 1730s, and angels supplanted them as the century wore on.

By 1834, the date on the stone on the right, limestone, which was easier to carve, was a more common material. Unfortunately it doesn’t weather well; the inscriptions on the left are tough to read without a lot of concentration.

This stone reveals the milder angels that replaced the death’s heads. In the 1700s and continuing to the very early 1800s, midword “S”‘s were printed and carved as lowercase f’s, without the crossbar, known in the modern era as the “long s.” It survives, sort of, in the German double s symbol.

Also note the use of poetry on the stones; most of the poetry on the stones concerned the deceased’s progression to the next life.

According to wikipedia, In the United Kingdom, Esquire historically was a title of respect accorded to men of higher social rank, particularly members of the landed gentry above the rank of gentleman and below the rank of knight. It later came to be used as a general courtesy title for any man in a formal setting, usually as a suffix to his name, as in “John Smith, Esq.”, with no precise significance.

Stones from the Mersereau and Corsen families from 1769-1795. These individula died in their fifties, which exceeded life expectancy then.

Judging from the condition of the sign, it’s one of the first generation of green and white street signs that replaced the previous Staten Island colors of gold and black. “Church Street” was of course named for the Dutch Reformed Church and its historic cemetery. The signs are unusually mounted on a slotted green post also holding a one-way and stop sign.

I have always been curious about a structure on the other end of the street near Park Avenue, tucked near the defunct Staten Island Railway trestle…

I had always been of the opinion that this small brick building had been the ticket office for the Port Richmond SIR station, which closed on March 31, 1953 along with the other North Branch stations. However a closer look reveals a doorway with the word “Men” over it. Theres’ no corresponding door with “Women” but while this building may have been SIR property, it was a lavatoire, not a ticket office or waiting room.

The SIR elevated sections, like this one at Port Richmond Avenue and Ann Street, are still in good condition; much of its grade crossings were eliminated in the mid-1930s, with management having no idea that closure was in the cards in just 15 years or so. FNY’s SIR page from 1999 shows several of the defunct North Shore stations.

Between Port Richmond and Park Avenues, Ann Street features a number of small dwellings untouched (except a coating of aluminum siding) for decades. On the corner is this tiny work clothes shop and a building with an oddly shaped roof whose function I can’t begin to guess.

Traditional apartment buildings with 16 or more units like this one at Ann Street and Park Avenue, while a familiar sight in the outer boroughs, are unusual in Staten Island except in the St. George area near the ferry terminal. However, you do see them in what were busier neighborhoods like Port Richmond, especially near what had been an active rail station.

You could probably cut your finger on the steep gables at 93 Park Avenue on the SE corner of Ann Street. The building was constructed around 1850 and was originally law offices for Lot Clark, the prosecuting attorney in a famed murder case in which a Polly Bodine was accused of murdering her sister-in-law and her sister-in-law’s daughter. After several hung juries Ms. Bodine was found not guilty, an outcome similar to the Lizzie Borden case.

A pair of terrific designs opposite each other on Ann Street between Park and Heberton. The double house in buff brick is unusual in Staten Island; note the shared porch (with divider) and polygonal bay windows.

This is a real find on Heberton Avenue between Ann Street and Richmond Terrace — I had not been by here before and had no idea these attached buff brick houses with individual porches existed before I took this walk. Note the details like the urns on the roofs, some of which have come off over the years. These buildings probably go back to about 1890.

Looking west on Ann Street toward the looming Bayonne Bridge.

Just past Heberton Avenue Ann Street makes an L-shaped turn, where it meets another street — which is to me one of the great mysteries of Staten Island.

This is a Beers atlas plate from 1873 depicting the Port Richmond street layout. The southwest has since been laid out, but other than that, the plan is still the same, centered around the shore-hugging Richmond Terrace, then called Shore Road, and Richmond Street, now called Port Richmond Avenue. Note the Eberhard Faber property at the top of the map. Most of the street names, though, have survived to the present, even Avenue B, which has gotten along nicely without an A or a C.

But why has there been an Avenue B at least since 1873 without an Avenue A? Pelham Bay, Bronx, has a similar mystery with a B Street without an A, but a little detective work cleared up that conundrum. However, the mysteries of Port Richmond’s Avenue B remain inscrutable.

Veterans Park

Port Richmond has its very own town square, Veterans Park, which shows up on the 1873 map and is still here, between Park and Heberton Avenues and Bennett and Vreeland Streets. Arrayed around it are several choice samples of Port Richmond architecture.

In fact this is Staten Island’s oldest park and has been here since 1836 when the majority of Port Richmond’s streets were platted. It was renamed in honor of American veterans in 1949.

In 1930 the Daughters of the American Revolution dedicated this stone monument on the Park Avenue side to participants in Sullivan’s Attack of August 22, 1777, when American Revolutionary War officer and political leader John Sullivan led an unsuccessful night attack on Staten Island (according to NYC Parks; most American initiatives in NYC an environs in the Revolutionary War ended in defeat or strategic defeat, but we prevailed anyway). The marker got a new plaque in 1998 when the DAR rededicated it.

On the other side of the park, at Heberton and Vreeland, is a decorative drinking fountain dedicated in 1915 to Eugene G. Putnam (1865-1913), a longtime principal of PS 20 (see below).

At Bennett and Heberton, facing the park, is one of the many attractive libraries built with the aid of a grant from Andrew Carnegie, the Scottish industrialist/philanthropist. I dedicated an entire FNY page to it in February 2017.

The St. Philip’s Baptist Church on Bennett Street next door to the library was organized in 1870 as a mission and met in local residences before finding a home at the Park Baptist Church (see below), in 1880; four years later, it acquired land on Faber Street and built its own church in 1889, incorporating as St. Philip’s in 1890. When the congregation outgrew the Faber Street church, it purchased this neo-Gothic church built in 1891. Longtime pastor Rev. Dr. William A. Epps, Jr., who served from 1954 to 1992, is honored with a street sign on Park Avenue.

The Mar Thoma Church of Staten Island, serving Syrian Christians based in the Indian state of Kerala (it’s complicated!) now occupies the 134 Faber Street site.

House of Multiple Gables: 120 Park Ave. at the SW corner of Bennett epitomizes the Colonial Revival architectural style. With a cool breeze and an ice tea on that wraparound porch you can save on air conditioning.

The twin-steepled St. Mary’s Orthodox Syrian Church holds down the corner of Park and Vreeland Street. The congregation started out as the Park Baptist Church in 1841 and constructed this Gothic Revival building in 1871; the corner steeple used to be much taller.

Another fairly large traditional apartment building at Heberton Ave. and Vreeland Street. As stated earlier, the building was constructed here because Port Richmond in its early years was more “urban” than other Staten Island locales and had its on nearby rail station until 1953.

Without a doubt (in my mind at least) the original Public School #20, which fronts Heberton Avenue with entrances on both Vreeland and New Streets, is the most magnificent structure in Port Richmond. It was constructed as the Union Free School in 1891 with an extension in 1898 in a Romanesque Revival Style, combined with neo-Classical and Queen Anne, with multiple gables, ornamentation and a clock tower. The site has been home to a school since 1841. The Landmarks Preservation Commission has given it protected status; it is now home to senior housing. The current PS 20 is a cross the park at Park Avenue and Vreeland Street.

A look at some of PS 20’s architectural detail.

“Comment..as you see fit.”

5/28/17