Strangely enough, though I have touched on Greenwich Street often (it runs from Battery Park up the West Side all the way through Tribeca and Greenwich Village into the Meatpacking District) I have never dedicated a FNY page to the street taken as a whole. (I have done a Greenwich Avenue page; the street is not to be confused with the avenue.) I had thought Greenwich Street would be fairly straightforward — but I shot about 250 photos along its entire length, which should be good for multiple posts and to move things along, I may have to do a midweek post.

Greenwich Street is fascinating. For one thing it used to be covered in its entirety by an elevated train, the 9th Avenue El, which from its terminus at South Ferry actually ran through Battery Park — can you imagine that today — and up Greenwich Street, and again, can you imagine an elevated train rattling through the now-tony precincts of Tribeca and Greenwich Village?

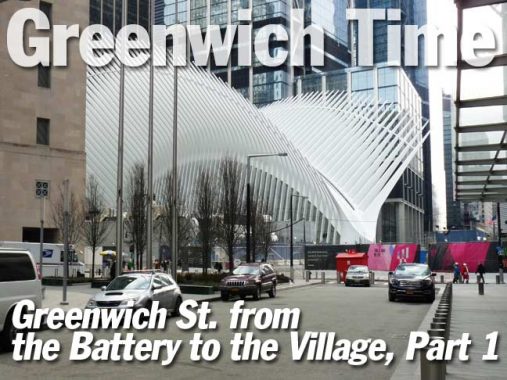

Greenwich Street runs alongside the Manhattan exit of the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel and was formerly interrupted by the original World Trade Center complex. The city is currently restoring Greenwich Street as a mostly pedestrian path through the new WTC complex. The street, of course, is named for Greenwich Village (which is actually a redundant name since in Old English, -wich or -wick means “village”.) It was built on landfill in stages between 1739 and 1785 and, at one point, ran along the waterfront. If you look at the map, it makes some subtle angles, following the old shoreline.

Had the 9th Avenue El been allowed to remain in place how would the city have handled its presence around those 20th Century works? It’s interesting to speculate. The 9th Avenue was NYC’s first el, going into service in 1868, and originally ran steam locos on one side of the street. The line was extended to West 34th Street by 1873 and West 155th by 1879, though expansion into the Bronx to join the Jerome Avenue el didn’t come until 1918. The line was rebuilt by the 1880s to accept heavy gauge trainsets (thus shadowing Greenwich Street and 9th and 8th Avenues uptown) and finally electrified by 1903. After almost 72 years of service, most of the 9th Avenue El went out of business in 1940, except a shuttle from the Polo Grounds to the Bronx, which also shut down when the Giants departed for San Francisco. I explored some remnants of this shuttle back in 1999.

Consider that between 1932 and 1940 there were three hulking elevated structures running lengthwise in southwestern Manhattan: the Miller (West Side) Highway, the West Side Freight Elevated, now rehabbed as High Line Park, and the 9th Avenue El! How did anyone get any sun?

Most Forgotten NY journeys begin at a subway station. Today’s trip up Greenwich Street began at the Bowling Green station serving 4 and 5 trains, an unusual station in many ways. Though it opened in July 1905, just a few months after the Original 28 Stations of the IRT opened in October 1904, it resembles a subway station built in the mid-1970s. In that decade it was given a complete makeover, eliminating its mosaic “wall tapestries,” which survive at the 72nd and 110th Street stations on the #2/3. Replacing them were walls of burnt orange brick, the “it” color of the early 1970s; the 49th Street station on the R/W still features it and the Lexington Avenue F/Q station did, before it had a center platform added that accommodated the new 2nd Avenue Line. Plaques showing historic images of the Bowling Green area were also added. New and old shots of the Bowling Green station can be found at NYC Subways. Just about the only vestige of the original station are the fluted tops and bottoms of the platform pillars.

Toward the south end of the southbound platform, you will see a disused platform across the tracks. This was originally used for shuttle trains to South Ferry. When Bowling Green was first built, all trains continued to travel south to the South Ferry station, but in 1908 the line was extended to Brooklyn’s Borough Hall. In 1909 the shuttle platform was constructed and those wishing to travel to South Ferry had to use a new shuttle line connecting the two stations. Then, in 1918, the new 7th Avenue IRT, today’s #1, was extended south to South Ferry, using its original curved platform, and the IRT needed to construct a new shuttle platform that year at South Ferry. Both sets of platforms are still in place at South Ferry, though neither is used today now that a new South Ferry station was built in 2009, destroyed by Hurricane Sandy in 2012, and rebuilt again. The shuttle line between Bowling Green and South Ferry continued in service until 1977, and can be used today in emergencies, though this platform remains unused. (A new platform to accommodate higher passenger traffic had been built on the east end of the station the same decade.)

This subway station house serves the IRT 4 and 5 lines and was constructed by early subway architects Heins and LaFarge in 1905. Other such remaining stationhouses include ones at 72nd Street and Amsterdam Avenue and at the Barclays Center station in downtown Brooklyn.

One thing that perplexes me about this venerable edifice… why is there a painted “Entrance” sign inside the stationhouse above the exit door?

The source of Greenwich Street, looking north from Battery Place west of Broadway. Seen in the rear of the picture are the new luxury high rise tower 5o West Street, #1 World Trade Center (the so-called “Freedom Tower”, and #88 Greenwich Street, a 37-story Art Deco tower constructed in 1929-30.

At Battery Place and Greenwich we find one of the Brooklyn-Battery (Governor Hugh Carey) Tunnel ventilation buildings, complete with bas-relief New York City, New York State, and Triborough Bridge and Tunnel Authority seals. The tunnel is the lengthiest vehicular underground tunnel in North America, opened in 1950 after several years’ delay due to materials being needed to build armaments during World War II. NYC traffic czar Robert Moses’ original idea was to build a suspension bridge from Cobble Hill to the Battery, but after vociferous protests, he capitulated and agreed to a tunnel (see Comment below)

The building doubles as the NYC headquarters of the Men In Black, a secret organization that monitors aliens, illegal or otherwise, living on earth, and protects against intergalactic threats.

Over the past decade, the Department of Transportation has installed Twin versions of the iconic Type B lamppost, generally used in parks but occasionally on side streets. There is a variant with scrolled masts.

This is the first address on Broadway, #1, the International Mercantile Marine Building, constructed in 1884 and resurfaced in limestone in 1922. It sits opposite the ancient Bowling Green that dates back to the Dutch Colonial era, and before the British occupied NYC between 1776 and 1783, General George Washington’s headquarters sat on the site. Though the building now hosts Citibank and other offices, its past as a shipping center remain obvious as terra cotta shields bearing coats of arms of great port cities can be seen between the windows on the second floor, while entrances are labeled “First” and “Cabin” Class. Inside, two gigantic murals that depict shipping lanes and a compass dominate the marble floor.

A grouping of NYC’s last “original series” Type 24M Corvington lampposts can be found on Greenwich and Washington Streets on either side of the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel exit. Though Type 24M “retro” version lamps are found frequently on major avenues in all five boroughs, these are the sole remaining Type 24Ms installed in the 1920s. There is also a collection of Type G Corvs to be found in Stuyvesant Town further uptown.

Look closely and you’ll see the spot where the 9th and 6th Avenue Els diverged. The 6th Avenue El ran above Trinity Place to Murray Street, then west a block to West Broadway, another block west on West 3rd, then north on 6th Avenue to West 58th, with a relay track above West 53rd connecting to the 9th Avenue.

That’s a lot of streets you never thought supported elevated trains in Manhattan, no?

A 2018 view of the junction of Greenwich, Murray and Trinity Place. Northbound Greenwich Street traffic is sifted onto Trinity Place; motorists who want to stay on Greenwich take Edgar Street one block west to pick it up again.

In these photos we see the massive Battery Parking Garage, which has dominated the tunnel exit since 1950, the year it opened. It originally had 1,050 parking spaces but even that proved insufficient, and so the annex seen on the left was constructed over the tunnel exit between 1964 and 1968. Years ago, I had an interview with Kinney Parking Systems in this building — I would have helped with layouts on their brochures. I didn’t get it.

In the foreground is one of the Battery Tunnel’s remaining General Electric M-1000 lamps, which resemble the GE M400‘s big brother. The tunnel was the only place in NYC where the 1000s were employed outside of parking lots. They were used extensively in other municipalities such as Albany, NY.

For years I had passed this signboard by on the traffic island/park, Elizabeth Berger Plaza, between Trinity Place and the tunnel exit ramp. It’s actually called a Litfaßsäule in German and a Morris column in English. FNY correspondent Sergey Kadinsky has the scoop.

Since its opening in 1950, the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel cut Morris Street into two pieces on either side. The two halves have always been connected by a pedestrian bridge; Sergey’s link in the above paragraph shows the old bridge, but a new one has replaced it. It’s now open to the public, but as of early 2018, permanent railings and lamps had yet to be installed — supposedly the railings will be illuminated.

Edgar Street is the shortest through street in Manhattan, underdistancing such competitors as Mill Lane a few blocks east and York Street in Tribeca. Its 63-foot length was named for shipping merchant William Edgar, who at one point in his career owned the biggest shipping operation in the city. For so short a street it is actually rather busy, with two lanes shuttling traffic between Greenwich Street and Trinity Place. It was moved a few feet, but retained, when the tunnel exit and parking garage were built.

In the foreground a townhouse going back to perhaps 1811 had become ruined and unstable over the years and was recently torn down. A glass box will replace it.

Edgar Street looking west toward Greenwich Street from Trinity Place in 1939. Note the 9th Avenue El at the end of the block.

85 Greenwich Street, just south of Rector, is the rear of 46 Trinity Place, an 1880 warehouse for American Express. If you walk around the corner, you can see American Express’s first symbol, a watchdog holding the keys to a lockbox. Just to its south, a now-demolished building was the original location of the Syms discount men’s suits store. I [purchased a suit there in the 1980s.

George’s Restaurant, Greenwich and Rector, is a frequent destination for post-tour lunches when FNY Tours take place in lower Manhattan. We used to go to any one of the restaurants on Stone Street, many of which came recommended, but not since one summer day we arrived, ravenous and thirsty at tour’s end around 3 PM at one of the places, Ulysses, I believe, and we were told, and not uncurtly, that the kitchen was closed at that hour and they didn’t have lunch for us. (This also happened at Indian Road in Inwood.) Thus, we always try and seek out a diner at the ends of tours in midafternoons. George’s may have a decent cabbie clientele as it is decorated in a yellow, black and white checkerboard theme.

Why restaurants are unable to dispense food during midafternoons is not understandable by me.

9/11 “Tribute Museum”, 92 Greenwich Street at Rector. I’ll link to, but won’t patronize museums dedicated to 9/11/01, no matter how well-intentioned; there’s something ghoulish about charging people to see museums “honoring” a day when people where jumping out of 90-story windows, preferring a fatal impact to burning to death. Yes, I know it honors and assists the first responders and their families. I’d rather donate to a fund.

94 Greenwich on the NW corner of Rector is one of the few 18th Century buildings remaining in Manhattan. It was constructed in 1798 and is one of three Federal-style townhouses in a row on the west side of Greenwich. Only 94 Greenwich, though, has most of its period detail intact including Flemish bond brickwork and original window lintels. In 1798 the building had a pair of 3rd-floor dormer windows but these were removed during an 1859 renovation when its 4th floor was added.

This can happen because the trio has never been protected by the Landmarks Preservation Commission, which, contrary to what many people believe, does not automatically convey protected status on buildings simply because of their age. Other factors such as social and architectural significance are considered. This leaves many buildings out in the cold and subject to the predations of developers.

Info: New York Landmarks Conservancy

#2 Rector Street, the 23-story United States Express Company Building, was constructed in 1907 with extra floors added twenty years later. The Rector Street side has a covered walkway, convenient on rainy days. In 1916, the Greenwich Street side of the building was heavily damaged when German saboteurs blew up explosives bound for war-torn France and Germany in what came to be known as the Black Tom incident. The crime was committed near an artificial island adjacent to Liberty Island called Black Tom.

The Riff Hotel is located in a relatively unadorned building at 102-104 Greenwich. Its true age is belied by a painted sign with serifed lettering just above the ground floor. It’s actually a palimpsest of two different painted lines of words atop the other, but I do make out the word “warehousing.” I make the lettering to be in the 1880s era; I hope building management allows them to keep showing though I doubt that will happen.

A teardown on the west side of Greenwich above Rector makes the back of Trinity Church at Broadway and Wall visible for at least a couple of months. For decades, this spire was Manhattan’s tallest after it was completed in 1846.

Without landmarking, you can get reimaginings like this, at 108 Greenwich. This was in 1835 the boyhood address of diarist George Templeton Strong, who by 1865 complained that Greenwich Street was “now a hissing and a desolation, a place of lager beer saloons, emigrant boarding houses, and the vilest dens.” [New York Songlines]

A large brick building with huge arched windows and the title “New York Curb Market” faces 123 Greenwich Street across from Carlisle. This is the rear entrance of the former American Stock Exchange Building facing Trinity Place. AMEX, now New York Stock Exchange AMEX Equities, began as the New York Curb Market Agency in 1908 and it was a legacy of the days when traders met on the street beside curbs (the NYSE originally met under a buttonwood tree). In 1929 the New York Curb Exchange was initiated, handling small stocks by new companies that were too “small fry” to be traded on the NYSE. The NYCE changed its name to American Stock Exchange in 1953.

Carlisle Street is a narrow lane running west from Greenwich Street to West Street. The origin of the name is in dispute. Sanna Fierstein (Naming New York) and the late Henry Moscow (The Street Book) often disagreed on NYC street name derivations. Feirstein insists no reliable source exists, while Moscow says Carlisle Pollock was one of three Irish brothers who ran a successful importing business here. Carlisle Pollock was the father of St. Clair Pollock, who died tragically from a fall near what would become Grant’s Tomb in the late 1700s, and is honored by the Amiable Child Monument.

At Liberty Street the towers of the new World Trade Center begin to loom. Greenwich Street has been extended as a mostly pedestrian path between Liberty and Vesey Streets.

In Part 2: through the new WTC site and into Tribeca.

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop, and as always, “comment…as you see fit.”

2/12/18