Today I’m going to expand on a recent piece I did in SpliceToday, as I am able to get a lot more expansive here with a lot more photos, and let my point of view wander around a bit more. There’s infrastructure to talk about, as some historical Queens lore.

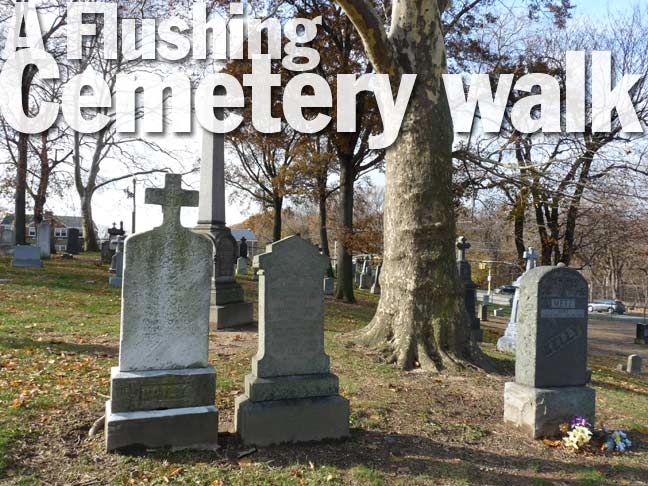

I was in desperate need of exercise after Thanksgiving. But where to go? Prospects of really good photos were minimal—the sky was mostly gun-metal gray much of the day. (For readers outside the Northeast, it’s been cloudy since Labor Day around here, with rain every other day, with an occasional snowstorm.) But then I hit on the right formula. I’d never been in Mount St. Mary’s Cemetery in the heart of Flushing, one of a trio of cemeteries in the same vicinity. I’d do a round-robin cemetery walk. I was so pleased with it, I’m thinking of doing the route as one of my Forgotten NY public tours in the summer of 2019, the 20th year I’ll be doing them.

I took the train to Auburndale, at Station Road and 192nd Street, and walked south.

GOOGLE MAP: FLUSHING CEMETERIES WALK

Before reaching the cemeteries, there’s some streetlighting business to take care of; there always is. There’s a lot of older mastarms that used to hold little orange lamps that indicated there was a fire alarm nearby. Form my earliest days I have been fascinated with the various methods of mounting them because they present interesting variations from the norm. The usual method to hang a fire alarm indicator lamp used to be a J-shaped pipe, pointing up; that’s the way the lights were affixed to telephone poles in most spots.

Occasionally you find a larger scrolled mast holding them, as here. Usually these masts were accompanied, on the telephone pole, by a longer mast that held an incandescent streetlamp. And usually, the fire alarm lamp was mounted on that mast. But when it wasn’t, it was placed on a shorter mast that you see here. A lot of those survived when the transition was made to the modern, finned streetlamp masts seen here. I estimate there are about 100 of the scrolled masts remaining, and I’m so obsessive that someday, I’d like to produce a five-boro map indicating where they are found.

Many of the fire alarms themselves are archaic, hewing to the same design introduced in 1913. Those are the ones with the torch on top that looks like an ice cream cone.

About a decade ago the city stopped servicing the orange indicator lamps and began to install very small red lights at the top of the streetlamp itself, as seen here. It’s a bad spot for them, especially when yellow sodium lights are still used, because the streetlamp drowns out the small red indicator.

Temple Beth Sholom, on Northern Boulevard and Auburndale Lane, is an interesting slice of modern architecture that is now also home to a Korean Christian congregation. Me, I always noticed the parking lot which features a modular Donald Deskey twin that uses its mastarms in a method not usually seen on NYC streets. The Thomas & Betts sodium fixtures shown here jockeyed for supremacy on NYC streets with other “sodes” made by General Electric and other brands.

Meanwhile here’s another Deskey lamp at 45th Avenue and Auburndale Lane, this one with a fire alarm indicator lamp. The Deskeys had their own individual design for the orange lamp covers, but here the city just used a regular standard-issue number. The city really never had a good way to affix these indicators and eventually, resorted to duct tape in a lot of cases, as it did here.

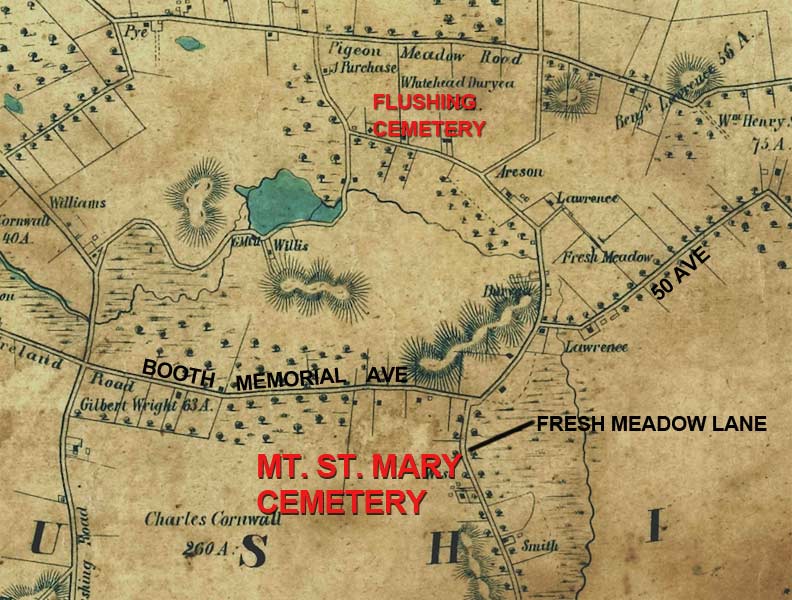

I ran across a couple more interesting fire alarm indicators, but first, a little history. This is part of the oldest map of Queens in my collection, from back in 1852. I’ve indicated the locations of two of the cemeteries I visited today. Flushing Cemetery and Mount Saint Mary’s. I’ll get into it a bit later, but Flushing and Mt. St. Mary’s were founded in 1850 and 1862 respectively and aren’t marked here.

Kissena Lake, which is now cut off from its feeder springs and is maintained as part of Kissena Park, is the blue blob in the middle. Though this part of Queens was still fields and farms in 1852, a number of the original roads are still in existence, though horses and carts no longer ply them and they’ve been converted to asphalt supporting heavy cars and trucks. The squiggly blotches indicate hilly terrain, while marshy ground is shown by small horizontal lines.

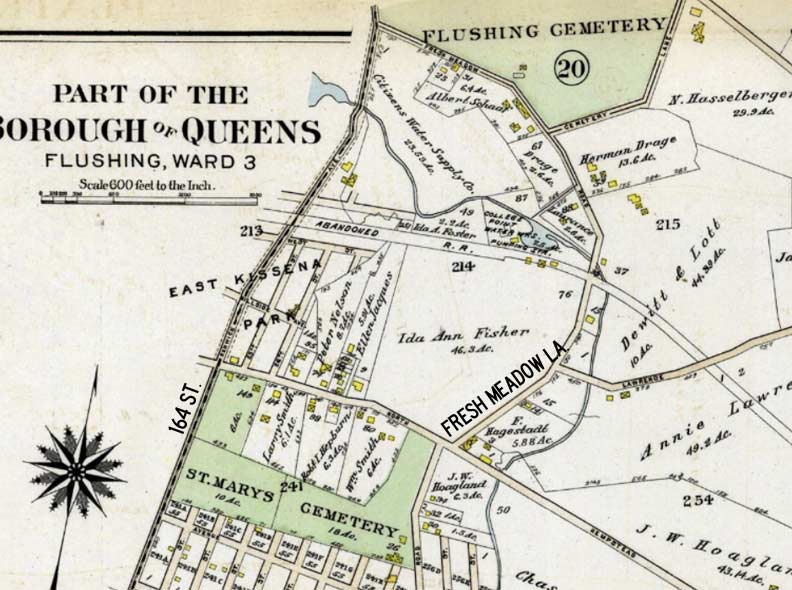

Moving forward to the 1909 map, we see both Flushing Cemetery and Mount St. Mary’s depicted; the latter won’t have its complete acreage until 1930. Much of the area was still fields. Ida Ann Fisher owned what would become the Kissena Park Golf Course. We see a couple of real estate developments such as East Kissena Park. Some, but not all, of the street grids of these developments would become part of the overall Queens street map.

The “abandoned railroad” down the center of the map is the Central Railroad of Long Island, which only operated for a few years in the 1870s. It was built by Irish department store king A. T. Stewart to connect what became the Port Washington branch of the Long Island RR with his new development in Garden City. Surprisingly, over 140 years later, a good deal of the railroad’s path can still be traced as Kissena Corridor Park and some unbuilt-on land in Queens Village. Part of the line was used as a spur to Creedmoor Hospital from the LIRR Main Line into the 1960s for steam engines pulling passenger cars.

Speaking of real-estate developments, there was one on the east side of Auburndale Lane opposite Flushing Cemetery constituting a series of streets in alphabetical order that continue with those names today: Ashby, Bagley, Courtney, Effington, Fairchild, Gladwin, with 47th Avenue filling in for the “D” avenue. At one time, they must have all had these brick gateposts, with only Bagley and Courtney’s surviving today. Some have lost their triangular “caps” and others have had their street names cemented over. The gateposts are very well made with alternating brick colors.

Meanwhile, here’s a short version of the fire alarm indicator scrolled mast at Auburndale and Bagley. These are quite rare; I’ve found a couple near Flushing Cemetery, one in Astoria, and a few in Morris Park, Bronx. This one has been out of commission for several years.

Fresh Meadow Lane is one of the oldest routes in Queens, beginning at Auburndale Lane at 47th Avenue and twisting south to meet Utopia Parkway between 69th and Jewel Avenues. Utopia Parkway is basically a straightened version of it. The lane appears on the 1852 map and probably goes back to the colonial era and perhaps even before that, as a Native American trail. It’s one of two roads in Queens with the word “Fresh” in the name (the other one is Fresh Pond Road in Ridgewood) and the word is used to describe non-salty water as opposed to brackish water. In the old days, streams or ponds of fresh water were important for their potability and settlements sprang up near such bodies of water.

In the stretch bordering the Kissena Park Golf Course, between Peck and Booth Memorial Avenues, Fresh Meadow Lane is sidewalk-free on the east side and somewhat resembles what it must have looked like many years ago.

I had thought that this dwelling on Fresh Meadow Lane and Peck Avenue was a renovation job, but the time machine feature on Google Maps shows it’s a new building. It employs the recent trend of vinyl exterior paneling, these in gray and orange. I don’t think it’s half bad, what about you?

Where there are cemeteries you’ll find marble monument firms. This one is on the NE corner of Booth Memorial Avenue and Fresh Meadow Lane. The FL telephone exchange stands for, as you might expect, FLushing and the number is dialed 357-9248.

Booth Memorial Avenue and Fresh Meadow Lane is a very old Queens intersection; you can see it on the 1852 map. Both are very old farm to market roads. Booth Memorial Avenue has had a number of names including Ireland Mill Road (it led to Ireland Mill Creek, which became Mill Creek, the feeder stream for Kissena Lake).

Ireland Mill Road later became North Hempstead Turnpike, a gloriously incongruous name since it did not extend out to the town of North Hempstead in Nassau County. In the tradition of NYC roads like Flushing Avenue and White Plains Road, it was likely named because it led to roads which would take you to North Hempstead. When the road was named in the 1800s, the town of North Hempstead was in Queens, but when Queens joined NYC in 1898, three of Queens’ easternmost towns opted out to become Nassau.

It was renamed in 1964 for Booth Memorial Hospital at Main Street. However, the ‘new’ name is now also outdated, since Booth Memorial became New York Hospital in the 1980s. So, let’s go back to the old name! (Won’t happen.) Both avenue and hospital are named for William Booth, founder of the Salvation Army.

Here’s a very old pull-handle fire alarm on the corner. It’s got a very old public service ad on it, depicting a fireman and the message, “False alarms cause death.” How old is the box? Well, it’s signed Edward Thompson, Fire Commissioner (invisible on this scan, but I’ve seen similar ones.) Thompson was in office between 1962 and 1965.

So, we’re finally ready for the first cemetery on the tour, Mount Saint Mary, which has two entrances on Booth Memorial Avenue, one the main gate near Fresh Meadow Lane and another, much smaller entrance near 164th Street. Though the cemetery has been here since the 1860s, its chapel and administrative buildings are relatively new.

Mount St. Mary Cemetery was founded in 1862 as an offshoot of St. Michael’s parish, today located on 41st Ave. in downtown Flushing. Eastern Flushing was farmland at the time, far from the town center at Main St. and Broadway (Northern Blvd.). The pastor at St. Michael’s, Father O’Beirne, procured portions of two farms for the cemetery. There were two later expansions, the latest in 1930, which filled out the cemetery to its present proportions. The Long Island (Horace Harding) Expressway was built on its southern border in the 1950s. The more recent interments, shown here, are in the cemetery’s eastern section.

Two figures in rock ‘n’ roll lore are buried in Mt. St. Mary’s, John “Johnny Thunders” Genzale (1952-1991) and Jerry Nolan (1946-1992) both from the New York Dolls, a band that never sold well, but were very influential, or “seminal” as the rock critics say. They were a hard-rocking outfit with outrageous frontman David Johansen, a native Staten Islander who later had hits under a different persona as Buster Poindexter. The Dolls took the stage in drag, but besides that gimmick, their talent was undeniable, and they influenced both the glam and punk eras of the mid- and late-1970s.

Other Mount St. Mary’s interments include Congressmen James Roe, Matthew Merritt, William Barry and Denis O’Leary; Emanuele Ronzoni Sr., founder of the pasta company; and Gambino crime family mobster Louie “The Bone” diBono.

The clubhouse for the Kissena Park Golf Course can be seen from Mt. St. Mary’s. The park had reached its present-day size by 1927 and the golf course appears on maps by 1940.

The park lies on the former plant nursery grounds of Samuel Bowne Parsons, and contains the last remnants of the family’s plant businesses. Parsons Boulevard is the road built in the 1870s that connected Parsons’ farm with that of Robert Bowne. A natural body of water fed by springs connecting to the Flushing River was named Kissena by Parsons, and is likely the only Chippewa (a Michigan tribe) place name in New York State. Parsons, a native American enthusiast, used the Chippewa term for “cool water” or simply “it is cold.” After Samuel Parsons died in 1906 the family sold the part of the plant nursery to NYC, which then developed Kissena Park, and the other part to developers Paris-MacDougal, which set about developing the area north of the park.

One of the newer monuments is in Irish Gaelic script. The O Laoghaire name is often rendered as O’Leary.

For me the western end of Mt. St. Mary’s is the more interesting, because it has the oldest markers, mostly Irish, some going back to the 1860s when the cemetery was founded…

…though occasionally there’s a wild card, like this one inscribed in German.

The Bartholomew McGowan memorial is in “white bronze,” actually zinc. Metal monuments are able to preserve just about all the details they had when they were first made, including the incredible trigraph of his initials. His wife and son are interred in the same plot.

Most of these zinc monuments came from the same company. M.A. Richardson of Chautauqua, New York, which devised the technique in 1873, was unable to succeed with the method and his rights were sold to the Monumental Bronze Company in Bridgeport, CT. in 1879.

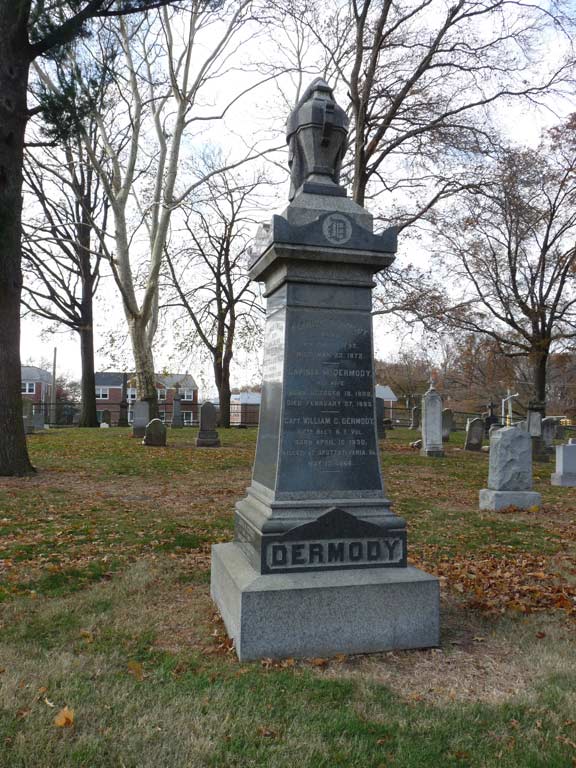

I recognized the marker of Captain William Dermody (1830-1864) who died at the Civil War’s Battle of Spotsylvania, because his name is also on a separate monument in Bayside at 46th Ave. and 216th St.—erected in 1866, it’s one of NYC’s oldest war memorials.

Plenty of room for recent additions.

Interesting how a family name spelling can change over generations. Here there are two spellings, Cain and the more common Kane.

After leaving Mount St. Mary’s I headed up 164th Street, one of the rare 4-lane numbered streets in Queens. Early in the 20th Century, this was a main north-south trolley route between Flushing and Jamaica, but after the trolley was removed in 1937, it became a major auto route at a time when the neighborhoods it runs through, such as Briarwood and Kew Gardens Hills, weren’t fully built out. It still retains its extra-wide status.

Opposite Kissena Park south of Underhill Avenue, there’s a large lawnlike area, with bare grass, just north of the golf course. It was formerly a bridle trail and indeed, there’s still a diamond sign signifying its presence on 164th Street. The south end of Kissena Park is still relatively undeveloped, with a winding bridle trail. However, the West Side Riding Club, at Auburndale and Pidgeon Meadow Roads, serving the trail, seased operations about a decade ago.

There are a wide variety of Department of Transportation diamond signs here, making horses, bicyclists, and kids crossing the wide road to get to the playground.

The main entrance of Flushing Cemetery is on 46th avenue at Pidgeon Meadow Road and 163rd Street. This is the cemetery’s main office building, 46th Avenue and 164th Street. This beautiful ashlar-stone Spanish-style building, designed in 1916 by architects York & Sawyer at a cost of $45.000, replaced Flushing Cemetery’s original two-story finial-roofed wood building.

The Flushing Cemetery Association was formed in March 1853; until that time, Flushing had many small church and family plots scattered here and there, but no large cemetery, and in April the Association bought approximately 21 acres from local farmers at 46th Ave. (then known as Queens Ave.), 162nd St. (then Fresh Meadow La.) and what is now Pidgeon Meadow Rd. Construction and landscaping proceeded apace and the new cemetery was dedicated August 31st of that year.

Pidgeon Meadow Road skirts the western and southern edge of Flushing Cemetery. The origin of the name is a mystery to me; perhaps Flushing Cemetery replaced Pidgeon Meadow when the cemetery was built in 1853? in any case the name is very old and you can see it on the 1852 map at the top of the page.

Louis Armstrong was and remains a Queens presence. Satchmo lived for three decades in nearby Corona and is buried in Flushing Cemetery. I’d never set foot in Flushing Cemetery until the summer of 2006, when I went to find Armstrong’s grave. Before starting Forgotten New York, I hadn’t been inside a cemetery since my mother died in 1974. I was rather comforted that Satchmo was only a couple of blocks away from me—when I lived in Flushing, I was at 43rd Ave. and 159th St.

His marker puts his date of birth on July 4th, 1900. That’s the date he preferred to give; records from New Orleans put the date ay July 9, 1901. Though he rose from poverty to become one of the most celebrated jazz trumpeters, latter-day audiences recognized him more from his unique singing on hits like “Hello, Dolly” and “It’s a Wonderful World.”

Musicians Dizzy Gillespie (who is buried in his mother’s plot and is not marked by a monument), Hazel Dorothy Scott and Johnny Hodges; Academy Award winner Jo Van Fleet (unforgettable as Arletta in Cool Hand Luke); US Congressmen Thomas B. Jackson, John Lawrence, Lemuel Quigg, Frederic Storm, Elmer Ebenezer Studley and William W. Valk; author and pastor Adam Clayton Powell Sr.; financier Bernard Baruch; restaurateur Vincent Sardi; Civil War hero and winner of the Congressional Medal of Honor, College Pointer Pvt. Carl Ludwig, are all interred in Flushing Cemetery.

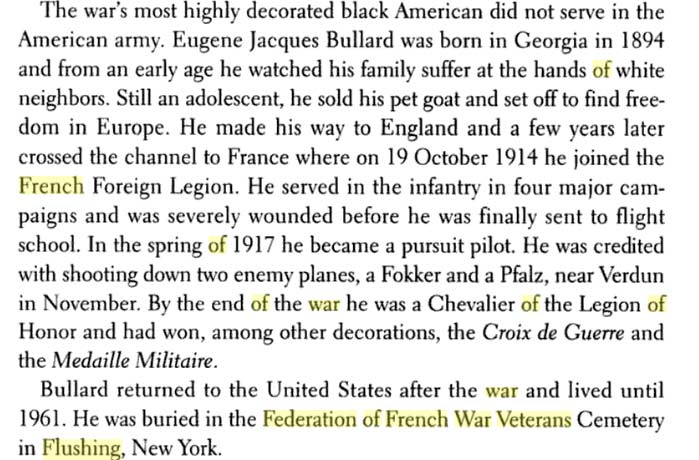

Though I have explored and written about Flushing Cemetery before, on this occasion I was surprised to find a section of the cemetery is reserved for French WWI (and later wars) veterans…

…and that one of the interments is Eugene Bullard (1894-1961), the first African-American fighter pilot, who fought for the French Foreign Legion:

Over There: The United States in the Great War, 1917-1918, Byron Farwell, W. W. Norton 1999

John Corwin’s monument is almost an exact duplicate of Bartholomew McGowan’s in Mount St. Mary’s, and it’s likely that the zinc marker was manufactured by the Monumental Bronze Company at around the same time.

The anchor at the top of Heinrich Uhl’s monument indicates he was a seaman of some rank. The marker notations are in German.

This fire alarm indicator is on 46th Avenue and 167th Street. Though it no longer functions, it’s in better shape than the other one, and its orange reflector cylinder is still in place.

Across the street from Flushing Cemetery is a plot that everyone had forgotten was a cemetery until quite recently.

When I moved to Flushing in 1993 and started bicycling around the neighborhood, I found 46th Avenue along Flushing Cemetery an ideal route — there were relatively few stoplights and intersections, and it was a convenient way to reach Glen Oaks, Hollis Hills, Bellerose and into Nassau. I used to pass a spacious, but nondescript, playground called Martin’s Field between 164th and 165th Streets. There were swings in the front, a sprinkler fountain, and the standard issue benches and lawns you find in a thousand other playgrounds around town.

However, Bayside historian and civil-rights activist Mandingo Tshaka had already been poring over real estate records and maps and had discovered that Martin’s Field lay directly on top of an old cemetery founded in the early 19th century and that over one thousand people, mainly African-Americans, Native Americans and also some whites found their final repose here, partially due to a cholera and smallpox epidemic that raged through Flushing beginning in the 1840s.

Ground in eastern Flushing was purchased from the Bowne family to inter the victims of these diseases, as contamination was feared if they were buried in Flushing’s already established cemeteries such as the St. George churchyard on Main Street. After the cholera epidemic had eased due to improved hygienic practices, the African Methodist Church of Flushing, which still exists today on Union Street, extensively used this ground for burials between about 1880 and 1898, when the last interment took place.

After that, however, the burial ground was completely forgotten as Flushing became more urbanized and streets and houses were built. The cemetery was acquired by the Parks Department in 1914 and in 1936 Parks Department chief Robert Moses developed it as a traditional playground, despite the fact that bones of the interred, along with the pennies placed on the eyes of the dead, were found during excavations. As a rule, Moses had no use for historic impediments to his projects, and not a lot of resistance arose against the playground project at the time.

And so Martin’s Field, named for conservationist Everett P. Martin, remained for the next sixty years. Hearing of Parks’ plan to renovate the playground in the 1990s, Tshaka embarked on a petitioning program, imploring local politicians and activists to reclaim the cemetery. These efforts finally met with success in 2004, as Queens Borough President Helen Marshall and then-City Councilman, now State Senator as of 2019 John Liu secured $2,667,000 to relocate the playground and add memorials that identified the cemetery, and re-landscape the hallowed ground.

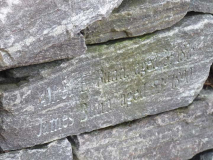

By the time Moses began turning the burial ground into a playground, only four headstones remained, three of them belonging to the Bunn family. A new memorial wall was inscribed with the names. A marble slab providing a brief history of the cemetery along with some of the names of those who are buried was placed in the ground, and circular walks and benches replaced the playground, which was moved to the rear of the former park space.

An interesting touch is the pavement inscriptions of four Native American words, Wompanand, Wunnanameant, Sowwanad, and Chekusawand. These are four of the 17 names of Algonquian gods transcribed by Roger Williams, the founder of Rhode Island, into his 1643 book A Key Into the Language of the Americas. The names can be found on the exterior of this paved circle in the center of the burial park.

Everett Martin’s rooters won’t be completely disappointed, as the conservationist’s name can still be found at the playground behind the burial ground, entered on 165th Street.

There’s a pair of interesting apartment houses facing each other on 165th Street between 45th and 46th Avenues. They’re quite similar, though not exact, with unusual entrances attained by a long corridor. They are respectively named Bremen Hall and Lindbergh Court, and from that I can infer that the developers were German, perhaps immigrants, and the buildings went up after 1927, when Charles Lindbergh made his solo flight aboard the Spirit of St. Louis from Roosevelt Field, Nassau County, to Le Bourget Airport outside Paris.

An apartment building I wanted to live in when I lived a few blocks away in Flushing, 43rd Avenue and 165th Street.

A dwelling with a red-brick exterior on 165th, between 43rd and Sanford, that I found appealing. Its old aluminum siding was removed around 2016 or 2017 and replaced with what you have now.

A veteran apartment building on 165th near Sanford. Apartment buildings of this type are often found near suburban railroad stations and indeed, the Broadway station on the LIRR Port Washington line is a couple of blocks away.

This building at 165th Street and Northern Boulevard, now home to a beauty parlor, restaurant and rental car office, started out as a Howard Johnson’s restaurant, as this 1940 tax photo indicates. HoJo, which formerly had hundreds of restaurants, now has just one in upstate New York.

At first glance, there’s nothing unusual about the Great Bear auto repair shop at 165th and Sanford, but it’s owned and operated by Audra Fordin, the first woman to run a Great Bear repair shop and possibly the only woman to do so anywhere in NYC. She inherited the shop from her father.

“I think different than men,” said the suburban mom. “When I talk about cars, I talk about things that you can relate to. You need air to breathe. Well, the air induction is the respiratory system of the car. The circulatory system is your cooling system. If your car has a fever, the gauge goes up and it leaks.”

Fewer than 1% of auto mechanics certified by the National Institute for Automotive Service Excellence are women, but for Fordin, fixing cars was a natural path.

Growing up, she spent weekends and vacations following her father Bill to work at the shop, which today still stands at its original location at the corner of 165th St. and Northern Blvd. on Sanford Ave. [NY Daily News]

Please help contribute to a new Forgotten NY website

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop, and as always, “comment…as you see fit.”

12/9/18

1 comment

Not long ago I was trying to figure out where my great grandmother was buried following her death in 1906. Her death certificate indicated only “Black Stump.” It was an earlier posting at Forgotten New York that provided the geographic clue leading me to suspect Mount St. Mary as the interment site. And upon visiting the cemetery, and checking their records, I found my suspicion confirmed. Accordingly there may be many more New York City death certificates that refer to the cemetery at Black Stump, rather than the formal name of Mount St. Mary. As noted, the oldest burials are in the western part of the cemetery (where my great grandparents are interred), while the administrative buildings are in the eastern part. Presumably, the main entrance had originally been on the west side of the grounds, where the trolley operated along what is now 164th Street, and was relocated to the east end much more recently.