I took a quick stroll east on 125th Street, crossing the 3rd Avenue Bridge into Mott Haven, west across the Madison Avenue Bridge back into Harlem again. Got some air on one of the few sunny days this season, and got at least some exercise in. As Yogi would say, you can observe quite a bit by looking, and I found some items I haven’t noted in Forgotten New York before. And, I beat it back to Penn Station before the rush hour fares kicked in at 4 PM so could get home on the relative cheap.

A look at Manhattanville east of Broadway from the elevated West 125th Street station. 125th Street cuts through the heart of Manhattanville, which was a village on its own before the overall Manhattan street grid crept north, and has kept much of its own grid, although the ancient street names are all but gone. Until the early 20th Century, 125th Street was called Manhattan Street, and after it was renamed as West 125th, it gained an intersection with West 129th, while 126th and 137th meet at a V where “old” and “new” grids meet.

Two magnificent iron bridges cross West 125th (also known as Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Boulevard): the IRT elevated viaduct carrying the #1 train and the Riverside Drive Viaduct, both built from 1900-1905. When IRT engineers were planning the subway, they chose to run a bridge over Manhattan Valley rather than make the subway tunnel deeper. The #1 train is closer to the surface than most lines, and shafts of sunlight illuminate some stations on bright days.

The short street Old Broadway issues north from West 125th Street near Broadway proper. Long story short, it’s a remnant of the original Bloomingdale Road, which meandered around northern Manhattan, eluding hills and streams. In the late 1800s, it was straightened, the hills leveled and the streams run into sewers, and became the north end of Broadway around 1890. The curvy parts of the roadway gradually faded out of existence, except for a couple of remnants such as Old Broadway and Hamilton Place.

Our Children’s Foundation, 527-535 West 125th Street, describes itself as “a non-profit organization which serves as an after school educational and recreational facility for the children of Harlem. The everyday operation consists of several classes in a variety of subjects with occasional assemblies and performances which bring in the community at large.”

The building it’s in has its own story. Manhattanville was once home to a number of milk bottling plants — the old Sheffield Farms plant, now a part of the Columbia University campus, can be found on West 125th west of Broadway. This building, still identified by its MBD trigram, was the McDermott-Bunger dairy plant. I’m not sure when they moved out.

Clinging to the north end of the General Grant Houses along West 125th Street is the NYPL George Bruce Library. “Completed in 1888, the original George Bruce Library was located on 42nd Street. When the building was sold in 1915, the proceeds were used to build the present-day, handsome, brick and sandstone, Carrere and Hastings-designed building on 125th Street.” [NYPL] Bruce (1781-1866) was a Scottish-American industrialist and philanthropist.

The Grant Houses were completed in 1956 at a cost of $29.2 million. 1,940 apartment units are contained within the apartments. With eight of the buildings at 21 stories, they were the tallest housing projects in New York City when built.

St. John’s Catholic Church, West 125th at Morningside Avenue, and its parish go back to 1860; the first Corpus Christi procession was held at the church. The Feast of Corpus Christi (Latin for Body of Christ), also known as Corpus Domini, is a Latin Rite liturgical solemnity celebrating the tradition and belief in the body and blood of Jesus Christ; according to Catholic teachings, Jesus transsubstantiated bread and wine into His body and blood at the Last Supper, and this is recreated at every Catholic Mass. As it turned out, a tour for Columbia U. alumna I gave in Manhattanville in early June 2018 turned out to be on Corpus Christi Sunday.

Roosevelt Triangle is located at West 125th Street, Hancock Place, and Morningside Avenue.

The bronze sculpture that now ornaments Roosevelt Triangle was donated by the Peter Putnam-Mildred Andrews Fund in 1976. This abstract piece, constructed from welded bronze plate and known as the Harlem Hybrid, is the work of Richard Hunt, an African American artist who has produced a number of public sculptures, most in his native Chicago, in a career that has spanned over thirty years. In New York, Hunt has exhibited his work at the Museum of Modern Art and the Studio Museum of Harlem. [NYC Parks]

Spirit of Harlem, glass mosaic by Louis Delsarte at 280 West 125th at Frederick Douglass Boulevard, created in 2004. It honors the Harlem Renaissance, a literary, philosophical and musical movement of the early 20th Century. Musicians Duke Ellington (who took the A train to get there), Cab Calloway, Paul Robeson, Billy Strayhorn and Count Basie called the neighborhood home, as well as civil rights activists W. E. B. Du Bois, Walter White, Roy Wilkins and the Rev. Adam Clayton Powell Sr (see below); literary giants such as Langston Hughes and Ralph Ellison; and jurist Thurgood Marshall.

125th Street received a makeover a few years ago that included some midblock stoplights. The crossings are marked by these stanchions that are embellished with paintings by local artists.

Hotel Theresa, now Theresa Towers, 200 West 125th Street at Adam Clayton Powell Boulevard. The 13-story former hotel, clad in gleaming white terra cotta, was built in 1913 (nobody was superstitious here) for German immigrant stockbroker Gustavus Sidenberg, who named it for his wife. It was Harlem’s tallest tower until the Adam Clayton Powell Jr. State Office Tower was built across the street in 1973. Amazingly, until 1940, it was segregated for only white residents until it was purchased by African American businessman Love Woods, who ended the policy.

The hotel became a cultural and gathering center for Harlem and was the site of speeches by Malcolm X and A. Philip Randolph. When Fidel Castro visited NYC to attend a United Nations session in 1960 he stayed at the Theresa, believing African Americans would be sympathetic to Cuba, and he attracted many area residents to hear him speak. While there, he was visited by Soviet premier Nikita Khrushchev and Egyptian president Gamal Abdul Nasser, as well as figures from the Harlem Renaissance such as Langston Hughes. Not to be outdone, John F. Kennedy campaigned for president at the Theresa the same year.

The hotel closed in 1967, and the building subsequently became an office tower.

7th Avenue above Central Park was renamed in 1974 for Adam Clayton Powell, Jr., the flamboyant and charismatic politician (1908-1972) who served 11 terms in the House of Representatives; in 1945 he became the first African-American from NYS elected to the House of Representatives, and he was the first black member of the City Council. After losing his seat and winning it back, Powell chose to retire to the island of Bimini, where he died in 1972.

Branley Cadet’s portrait, “Higher Ground,” was dedicated in 2005.

The former Koch & Company Department Store, once one of Harlem’s largest, was founded by German immigrant Henry Koch (1831-1900) in Carmine and Bleecker Streets in Greenwich Village in 1860, moved to 6th Avenue and West 20th Street in Ladies’ Mile in 1875, and finally to 125th Street in Harlem in 1891, hiring architect William H. Hume to design the grand emporium. This section of 125th was residential at the time, and the massive department store spurred the conversion of the street to the retail mecca that it is today. In Daytonian in Manhattan, Tom Miller has a lengthy piece describing the opulent store in detail.

Henry’s son E. Von Der Horst Koch ran the department store after his death, but after the son died in 1930, the store foundered and went out of business in 1932.

We’ve seen the Hotel Theresa…here’s the considerably more unsung Bertha, on 16 West 125th near 5th Avenue.

13-15 East 125th Street, now a storefront church, is marked by a pair of caducei, or a staff encircled by two snakes. The symbol is associated with Hermes, the Greek messenger god (the Romans called him Mercurius) and it was generally found on commercial buildings from the 18th and early 19th Centuries. It was also used as a symbol for speed — a caduceus can be found on remaining stations or overpasses of the NY, Westchester and Boston Railroad in the Bronx, much of which is now the Dyre Avenue line (#5 train).

It’s a commonly made mistake equating the caduceus with the medical profession. In medicine the symbol is the Rod of Asclepius, which has one entwined snake, not two.

A vintage shoe polish ad can be seen on the side of 1963 Madison Avenue, north of East 125th. It was apparently one in a series of ads by the same company painted in the same spot because the one in this 1920s photo, on the same building, looks different.

It’s a “pythy” at 54B East 125th just off Madison, which is an 1891 Knights of Pythias hall. It wraps around the corner and also fronts on Madison. The Knights moved out decades ago. Another one of their former buildings is an Art Deco masterpiece on West 70th Street off Central Park.

The fraternal organization Order of the Knights of Pythias was instituted in 1864 by Justus H. Rathbone and was actually the first such organization to be granted a charter by the US Congress. The name was inspired by the story of Damon and Pythias, an old story of loyalty: in ancient Syracuse, Pythias was accused of plotting against a tyrant, Dionysus I, and sentenced to death. Wishing to return home to settle affairs, Pythias entreatied the tyrant to allow him to do this, but, of course, believing Pythias would not return, Dionysus refused. Damon offered to take his place, and Dionysus relented on the provision that if Pythias did not return by the day agreed upon, Damon would be killed instead.

On execution day, Pythias arrived at the nick of time, explaining that pirates had captured his ship, he jumped into the sea and swam and ran to Syracuse to make his appointment. Dionysus, so impressed by the pair’s show of loyalty, spared both.

The Knights of Pythias claims over 50,000 members worldwide; Presidents McKinley, Harding and FDR have been members; NY Senior Senator Charles Schumer and US Reps. Anthony Weiner and Peter King are/were also Knights of Pythias.

While the first leg of the 2nd Avenue Subway opened from Lexington Avenue to 96th Street as a northern extension of the Q train, construction on Phase II between 96th Street and Lexington and 125th Streets is expected to begin in 2019 with the extension opening in 2027. Will I be around?

The former Harlem branch of the Corn Exchange Bank at East 125th Street and Park Avenue, a magnificent ruin for nearly two decades, was recently given a new lease on life as five new floors were built on the remaining lower floor in a fair imitation of the French Second Empire style. It’s not a rebuild of the former bank, but rather a reinvention of it. The bank was constructed in 1883 as the Mount Morris Bank, the Corn Exchange took over in 1913, and after other acquisitions, the bank moved out in 1965. Various tenants such as day care centers occupied the building before a fire destroyed everything but the first floor in 1997. See David Dunlap’s NY Times report from 2014 on the new-old building.

125th Street Metro-North station, under the elevated line on East 125th. The interior is handsomely wood-paneled, but I didn’t feel like hassling with cops or Metro-North personnel about photography, which is perfectly legal; sometimes officials refuse to acknowledge that or actively flout it. Untapped Cities, which has more resources and “ins” than FNY, did get in and acquired some shots. The most recent renovation was in 1999.

Here’s another grand old pile, this time unreconstructed but original, the Harlem Savings Bank on 124 East 125th just off Lexington.

The Harlem Savings Bank built its clunky neo-Classical bank at 124 East 125th in 1907. The architects Bannister & Schell were overreaching toward the City Beautiful style, and wound up with the City Chunky. (Around the corner, at 124th and Lexington, the little Provident Loan Society building from 1911 offers a more peaceful repose.) [the late Christopher Gray in the NY Times]

I ambled north then east, on a complicated pedestrian path that goes over and under the East River Drive to the 3rd Avenue Bridge over the roaring Harlem River. This is a look at the northern end of 3rd Avenue in Manhattan, the northernmost point the avenue is marked with a numeral. It continues on in the Bronx under the moniker “Third Avenue.” When the Third Avenue El was extended into the Bronx in the 1880s, a number of streets accompanying it were renamed for the Manhattan avenue, and that’s how a Manhattan avenue got into the Bronx.

The towers in the background are the Jefferson Houses.

Crossing the “new”3rd Avenue Bridge. It’s the 4th bridge in its location, replacing bridges constructed in 1797, 1868 and 1898, and the newest one, having been completed in 2005 after damage from a 1999 fire prompted the replacement of the 1898 bridge, a swing span designed by Thomas C. Clarke as the sister bridge of the Willis Avenue span. The 3rd Avenue El, by the way, did not run over this traffic and pedestrian bridge but rather had it own span over the Harlem.

On a spring day in 2009, I crossed five Harlem River bridges and lived to tell about it. A couple of them have been replaced since then!

Since I crossed the bridge in 2009, the old yellow sodium lamps have been replaced with LEDs. I recognize the Cooper Archeon, which is standard issue in the Bronx, but can anyone tell me what make the lengthier one is?

The Steinway piano factory across the East River in Astoria, Queens, may be better chronicled, but Mott Haven certainly had the greater number of piano manufacturers, enough so that the South Bronx was known as “The Piano Capital of the United States” prior to World War I. The Krakauer Piano and Estey Piano works, at E. 132nd St. between Lincoln and Alexander Aves. and Kroeger Piano at Alexander Ave., whose buildings are still standing, catered to a burgeoning piano-playing clientele in the days before radio and TV. These factories also produced player pianos. Krakauer supplied over 1000 pianos to New York City’s public schools until its Bronx factory closed in the mid-1970s.

Estey, centered in Bluffton, Indiana since 1869, built a marvelous clock-tower building at Lincoln Ave. and Bruckner Blvd. (then E. 133rd St.) in 1888. That building, shown here, still survives today after being re-purposed for residences.

The original piano pioneer in the South Bronx was the Arion Piano-Forte Company, built by George Manner and sold to J. Simpson and Company who moved it to 3rd Ave. and E. 149th St. in 1872; which in turn sold to Estey in 1885. Other piano firms included Dunham and Sons, Denobrica, Stuyvesant, Dusinberre & Co., Haines Brothers, Newberry & Evans, and Jacob Doll & Co., who distributed Pianola piano rolls.

Real-estate developers have been trying to rebrand Mott Haven as “Piano Town” or something similar, but gentrification hasn’t gotten untracked in the area and perhaps will never.

Squeezed in between the Harlem River and Yankee Stadium in the southernmost Bronx is a small neighborhood known as Mott Haven, after Jordan Mott, who built a tremendously successful iron works beginning in 1828 (the iron works continued to 1906), centered along the Harlem River from about 3rd Ave. to E. 138th St. His handiwork is still seen all over town on airshaft and manhole covers built by the Mott Iron Works. Mott bought the original property from Gouverneur Morris II in 1849; Morris was asked if he minded if the area was called Mott Haven, a name it had quickly acquired. “I don’t care… while [Mott] is about it, he might as well change the Harlem River to the Jordan.” The iron works produced practical and ornamental metalwork used worldwide.

In 1850, Mott drew up plans for the lower part of the Mott Haven Canal, which followed an underground stream parallel to Morris Ave. and east of the Harlem River. When completed, it enabled canal boats using the canal to go up as far as 138th St., encouraging the local industrial development. It has since been filled in. Residential neighborhoods, such as the one that forms the Mott Haven Historic District, are not common in Mott Haven. After 1856, Mott Haven joined with several other villages to form the town of Morrisania, although the area still continues to be known by its original name.

The remaining Mott Iron Works buildings are still standing west of 3rd Ave. between E. 134th St. and the Harlem River, and one is still marked with its old name.

The staircase on the 3rd Avenue span is quite steep, and grabbing the handrail is recommended. At the bottom is the west end of Bruckner Boulevard at 3rd, I mean Third, Avenue.

On a fence surrounding an empty lot, a street artist has placed stenciled mermaids labeled “Mami Wata.” I thought this may be an ad for a nearby nightclub, but Mami Wata is a water-based often-female deity worshiped in western and central Africa, sometimes depicted as a mermaid, sometimes with two legs. It’s interesting how mermaids appear in many cultures and continents.

I have always wanted to visit the Mott Haven Bar & Grill, located in an otherwise desultory corner of Third and Bruckner. It carried the address #1 Bruckner Boulevard. We may have had our chance when a Forgotten NY tour was in Mott Haven in 2014, but the former Bruckner Bar & Grill was still closed because of flooding from Hurricane Sandy. At length, the venue reopened under new management as the Mott Haven Bar & Grill, but in 2018 the old Bruckner neon sign was still in place.

Bruckner Boulevard is one of the Bronx’s longest roads. It was assembled from a number of different roads in the early 20th Century as Eastern Boulevard, and was renamed in the 1940s for a Bronx borough president after his death. For most of its length, as far as Pelham Bay Park, it is the service road for the Bruckner Expressway, built in sections between 1959 and 1972.

Artwork outside the Mott Haven Bar & Grill. You got me — the Comments section is yours, if you know what this is.

Here’s a Westinghouse OV-15 “Silverliner,” sort of a little brother to the Westy OV-25 that battled for supremacy in NYC streets with the GE M400 during the 1960s and 1970s. The OV-15s weren’t used in NYC, but I saw a few in Port Washington in Nassau County when I worked there.

A long-ago office building on East 134th near Third Avenue with an arched entrance and windows on the second floor uses yellow-colored bricks more commonly seen in western Queens (Astoria, Ridgewood, Glendale). They may come from the Kreischer brick works in Staten Island, which produced tons of light brown to yellow bricks in the early 20th Century. The original owner, P.M. Ohmeis, is bricked at the roofline. Peter Ohmeis was a beer distributing firm between 1880 and 1906, dealing with Schlitz exclusively.

These little architectural gems are the minuscule repositories of NYC history. The door was open, but a glance inside revealed a busy workplace, not much to seize upon and write about. The giant Mott ironworks was just across Third Avenue from here.

I was happy to see an iron works and other industrial stuff across the street. The Bronx still works, and hasn’t been gentrified yet.

Graham Square, now called Graham Triangle, is one of the Bronx’ major crossroads as here E. 138th St., Lincoln Ave., Morris Ave. and Third Ave. all come together. The intersection’s marked by two war memorials; the one on the north side honors area World War I soldiers and was unveiled in 1921.

This memorial, on the south side of the square, is more interesting to me because it’s one of the few major Spanish-American War memorials in New York City.

Although it was a short war with a questionable mission, the sacrifice of American troops during the Spanish-American War is also commemorated by several memorials across the city. A column erected in 1919 at Graham Square in the Mott Haven section of the Bronx is dedicated to those from that community who served and died. In 1941, a large granite stele was dedicated to Spanish-American War veterans in Captain George H. Tilly Park in Jamaica, Queens. (Tilly, the son of a prominent Jamaica family, was killed while fighting in the Philippines in 1899.)

The most significant Spanish-American memorial in the city is the grand Maine Monument (1912) at Central Park’s Merchant’s Gate at Columbus Circle, that honors the 258 American sailors who perished when the battleship Maine exploded in the harbor of Havana, Cuba, then under Spanish rule. Soon after, newspaper publisher William Randolph Hearst agitated for war with Spain.

Classic Ionic columns and pilasters (half columns attached to a building front) punctuate this 1912 design by Albert Davis. It’s called the North Side building because Manhattan and the Bronx once formed New York County, and this was north of downtown Manhattan. Cell phone relays chill the mood.

Morris Avenue, one of the Bronx’s longer, yet more unsung avenues, issues north from Graham Square. It’s named for the Morris family which one owned most of the south Bronx.

Gouverneur Morris (1752-1816) half-brother of Lewis Morris, was a political leader, diplomat, U.S. Senator, and American ambassador to France. He was an outspoken opponent to what he termed “unchecked popular democracy.” His son, G. Morris II, sold the estate to Jordan Mott.

Gouverneur Morris was outspoken and brash—nonetheless, he became ambassador due to his thorough familiarity with the French. In his youth, he’d drive teams of horses without the benefit of reins, yelling and cracking a whip instead, but one day one of his teams ran off and he was dragged, winding up with a crushed leg. For the rest of his life he hobbled along on a wooden leg, like a Dutch predecessor, Peter Stuyvesant.

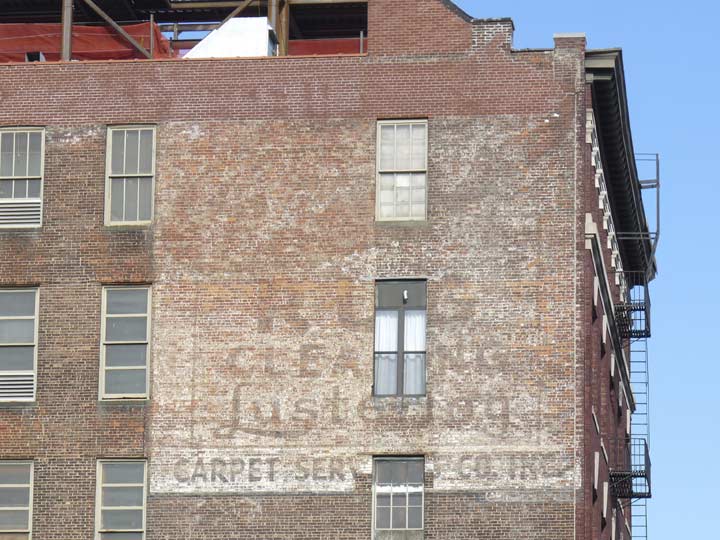

A couple of items on Canal Place north of East 138th Street: first this rapidly fading ad for a rug & carpet cleaning service…

…. and Nick’s Blue Diner on the corner of the two streets was shuttered, but it had received a Yelp review as late as May 2018, so there’s hope. It’s a 1948 Kullman model in almost original condition. Once again, hit me in Comments if you know anything.

Mott Haven has a run of streets named Canal Street and Canal Place, indicating the former Mott Haven Canal. Sergey Kadinsky has the full story.

The Conk begins here, at Easy 138th Street and an off-ramp from the Major Deegan Expressway.

The Grand Boulevard and Concourse marches north from the Major Deegan Expressway to Mosholu Parkway through Mott Haven, Concourse Village, Mount Eden, Mount Hope (the Concourse is constructed on a hill), Fordham, and Bedford Park.

Eleven lanes wide from 161st Street north to Mosholu, the GB&C (shortened to Grand Concourse for the benefit of sign makers and cabbies) was built, from 161st Street north, in 1909 by engineer Louis Risse. In 1927, it absorbed Mott Avenue, which ran from 138th north to 161st, and the older street was widened. The Grand Concourse became the Bronx’s showpiece as the Bronx County Courthouse, Yankee Stadium, and an array of elegant apartment buildings were constructed along its length. The Concourse and surrounding streets are a wonderworld of Art Deco…spend an afternoon along its length and observe the sumptuous buildings.

The Concourse is dominated by two separate architectural trends. The Art Deco style, characterized by highly stylized and colored ornamentation, ironworked doors, colorful terra cotta and mosaics, originated at the 1925 Exposition Internationale in Paris. Art Moderne, noted for its striped block patterns, cantilevered corners, stylized letterforms and generally streamlined appearance, first gained wide notice at the 1937 Exposition.

The Latin Bronx motto, Ne cede malis, means, “Yield not to evil.” It appears in these medallions on the Deegan overpass and on the Bronx borough flag, which is shown in terra cotta form here.

The eternal question for Bronxites is… who was Major Deegan? This park oval at the west lane of the Concourse and East 138th explains it all.

Major William Deegan (1882-1932) constructed Army bases in and around New York during World War I. He was a State Commander of the American Legion, a Commissioner of Public Housing, and a close friend of Mayor Jimmy Walker, who appointed him Commissioner of Tenement Housing in 1928. He died from complications after an appendectomy at the young age of 39.

The expressway named for Deegan was constructed in stages beginning in 1944. By 1956 the road reached the Westchester county line, where it changes its allegiance to New York governor Thomas E. Dewey and runs north and west to Buffalo; motorists know it best as the New York State Thruway. Dewey, a Republican, was NY state governor between 1943 and 1955. He lost for President to Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1944, and ran again against Harry S Truman in 1948. He apparently had eked out a win and, in fact, some newspaper headlines reported his victory. Truman, however, enjoyed a late surge and proved the headlines wrong. Dewey was the last major-party candidate to wear a mustache.

East 138th Street slopes down to the Harlem River where it dead-ends, offering a view of the Madison Avenue Bridge.

I returned to Manhattan via the Madison Avenue Bridge, which connects the Manhattan avenue with East 138th in the Bronx.

The Madison Avenue Bridge was opened in 1910 and designed by architect Alfred Pancoast Boller (1840-1912), replacing an earlier bridge opened in 1884, also designed by Boller. As with this bridge and the Macombs Dam Bridge up on 155th Street, Boller was a proponent of ornamental ironwork, making his bridges among the city’s most beautiful vehicular bridges. His work was so admired that a Bronx avenue in Eastchester was named for him; though Boller Avenue was mapped to run continuously from Crawford Avenue to beyond Stillwell Avenue at the Hutchinson River, much of it has been swallowed by Co-Op City. A few blocks of it still remain.

Each of Boller’s Harlem River spans feature little stone houses on either side of the river. I am not sure what their function was other than provide a booth for guards providing safety for pedestrians passing across the bridge. They are unoccupied these days.

Before getting back on the #2 train at 135th and Malcolm X (Lenox) I noticed that the Riverton Houses is now using “acorn” style luminaires. There were in use on heavily trafficked streets in NYC from the late 1910s up to the 1940s, when they were replaced by Bell and Gumball fixtures.

Please help contribute to a new Forgotten NY website

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop, and as always, “comment…as you see fit.”

12/30/18

4 comments

While the Spanish-American War may be a historical footnote in most respects, one incident during the conflict changed the world firearms industry in a way that continues to this day. The US Army suffered over 200 deaths during its attack on what should have been a much weaker Spanish detachment on San Juan Hill, because the Americans were armed with clunky Krag-Jorgensen rifles chambered in the relatively inaccurate 30-40 Krag cartridge, while the Spanish had fast-cycling, extremely accurate 7mm rifles from the Mauser company of Germany.

Chastened by this unfortunate outcome, the US embarked on the development of an accurate cartridge for use in modern rifles, which became the famous 30-06. It served as the main US military cartridge for two world wars and was in use over a span of 60 years. Even to this day the 30-06 is the world’s most popular big game hunting cartridge, and two of its derivatives, the 270 and 308, aren’t far behind. All because of a single battle in a nearly forgotten war.

Real-estate developers have been trying to rebrand Mott Haven as “Piano Town” or something similar, but gentrification hasn’t gotten untracked in the area and perhaps will never.

You may want to check out this article:

https://www.npr.org/2017/08/02/540638655/forget-the-bronx-is-burning-these-days-the-bronx-is-gentrifying

Thank u 4 yr splendid work throughout the City. I’m delighted my beloved Mott Haven has received yr attention. Sadly we left in 1960 after my grandfather was mugged in the vestibule of 587 e 137. B 4 then our time was like many other nbors shopping at Woolworth, family entrance dining at Gallaghers, quick stop at the corner subway cigar stands where I bought 2 comic books and a 5 cent candy bar all 4 the princely price of 25 cents. St Luke’s R C held both a low and high mass in the lower and upper church. I loved going to school there. Still miss the nborhood even after living on Long Island, the Village, Boston, and now West coast. Thank u again. Sad 2 c my former home all boarded up. I bought a NYC Archives 1940 photo of the bldg, pricey but glad 2 see it back then. Many memories returned. My grandfather was the nborhood barber w a shoeshine stand across the street from his shop.

Again thanks. Maybe some day I can take 1 of your tours w in THE City.

Nick sold diner. and adjacent building. The future probably will be an apartment house. And we call it SoBro.