The MTA trots out ancient subway rolling stock a few times a year, on Mets and Yankees opening days and other events, but most notably on Sundays during the holiday season in November and December and also twice a year, at its “Parade of Trains” in which four sets of trains manufactured from the 1900’s through 1960s run from the Brighton Beach station to Ocean Parkway or Kings Highway. In past years the “Parade of Trains” was held in June, but this year (2019) it was moved to September.

My intention was to catch a ride on the three vintage trainsets that were running from Brighton Beach to Kings Highway, and that left out the relatively “new” set of R33-R36 trains that were going to Ocean Parkway. As you’ll see here, I got a number of photos, but the crowds, which were larger than ever on a sunny, warm 80-degree afternoon, largely interfered with acquiring really good ones. To be frank, the crowds, which were well-behaved and in good spirits for the most part, put me in a rather cross mood, but that’s something to discuss with my psychiatrist, if I could afford one.

It was my intention to wander up to L&B Spumoni Gardens on 86th Street for a couple of “squares” for lunch, but the day wrapped up at 3:30 for me, and lunch would have spoiled dinner. I did get through some interesting aspects of Brighton Beach, though, which I’ll render below.

Remember, clicking in any photo in a Gallery, which shows 2 or more photos, enlarges the picture.

The first set to roll into the Brighton Beach station was a set of R1-R9 trains from the 1930s, the first subway cars in NYC to have the “R” for Revenue prefix; the R is still used today, and with some skipped numbers, we’re up to R-211, the newest cars in production that will see the tracks soon. These aren’t the cars I rode as a kid, but the white porcelain handholds, exposed lightbulbs (legend has it the screws were made in an opposite direction from usual to prevent theft), overhead fans, roll signs and wicker seats are all elements I recognize as a child that were in other subway car models still in use.

Forgotten Fan Allan Rosen: No R numbers are skipped. Every number is used. The numbers you don’t know about are for non-revenue vehicles such as the garbage train and track geometry cars.

I do remember very old cars in use on the L line when I made a rare trip to Ridgewood from Bay Ridge in 1975, and I read that the R1-R9 was in service until 1977, so they may very well have been on the L line in their final days. Subway aesthetics have gotten extremely streamlined, reflecting overall building trends, in the century plus between 1905 and today.

Forgive the occasional blurry photo. The trains rattled and rolled in motion, and getting clear shots in such conditions requires a tripod, an accessory I don’t have — and for which there would be no room in any case. Amelia Opdyke “Oppy” Jones’ public service ads were a subway staple for decades.

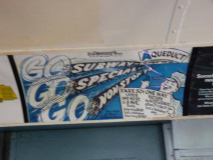

This one advertises a special express train running from the 8th Avenue 42nd Street IND station direct to Aqueduct Raceway, the “train to the races” as it was. These trains ran from a lower level of the 42nd Street station that has been abandoned for years. FNY showed this station with the help of Mike Epstein, who used to run a photoblog called Satan’s Laundromat (his address was 666 and he lived over a laundromat at the time).

Another “Oppy” advises people to beat the crowds by taking the local, a trick I occasionally employ. In the 1940s, when these posters were produced, the only relief from heat came from overhead fans and open windows.

“Subway Readers,” which were actually numbered, these being Nos. 31 and 39, dispensed NYC trivia to harried commuters who may or may not have been interested; I would have been. The tunnel the 4th Avenue horse cars used is still in place on Park Avenue, but now it’s home to pedal to the metal traffic.

Exterior of an R-1, complete with exposed rivets.

These blue and white cars on the R-33 fleet produced in 1933 1964 ran on various lines on the IRT until 2003, when they were permanently retired. They didn’t look like this, though: by 2003, all were painted a deep maroon red (and some were dark green for a time, but not by 2003). They acquired the nickname “redbirds” in the 1980s. Their original blue and white paint job for the 1964 World’s Fair never earned the name “bluebirds,” though, since an earlier set of experimental subway cars had already claimed the name!

Next to the platform was a BRT/BMT Standard set built in 1916. These were the first cars to employ electric lights in the cars: previous cars used lights using kerosene. Standards measure 67 feet long and 10 feet wide and contain 78 seats with an additional 14 drop-down auxiliary seats. The cars were able to handle 182 people per car including standees. Somehow, some of the Standards remained in service until 1969. They were originally built for Brooklyn Rapid Transit, which reorganized into Brooklyn-Manhattan Transit after the Malbone Street Wreck bankrupted it in 1918.

Although the Standards attained good speed running down the express track of the Brighton Line, the car I was in, #2392, was in poorer shape than most, with its rattan seats peeling off. A Transit Museum worker spent 5 minutes getting a recalcitrant door to close. In comparison to today, the doors are built strangely, with a two-door entrance around a center shaft; Dashing Dans in a rush may have crashed into the shaft on more than one occasion.

In the vintage ads category, I decided to concentrate on products available today. In reality, Heinz, best known today for ketchup, mustard, and baked beans in Britain, always produced many more varieties than the “Heinz 57” products advertised. A former Heinz factory on Bergen Street in Prospect Heights is still clearly marked. Also, Rheingold, a future New York Mets sponsor, produced “near beer” in the Prohibition years of 1920-1933.

The Campbell Twins used to be a bit older, and hunted large tomatoes.

A look at the Standard’s porcelain handhold bar (the Standards did not have straps) and original light fixture. (Operators briefly lit up the R-1 bulbs, but not the Standards or Brooklyn Union elevated cars I rode in today.) The grate is likely for ventilation.

The Standards have signboards in the center of the cars for ads; modern subway cars have electronic versions that give the next station, the time, and public announcements. Both these ads are from the WWII years when these cars were still in service.

If you haven’t heard of Burma-Shave, the shaving cream had an amusing advertising campaign from 1925 to 1963 when the company would install 5 or 6 consecutive signs along highways, containing a humorous rhyme with the final sign in the series advertising the product. After 1963 when Burma-Shave was sold to Gillette, the signs were discontinued.

The riveted exterior of the 1916 Standard.

Next to the platform was a three-car set of Brooklyn Union Elevated cars built in 1904, by far the oldest cars in the MTA that can still run, due to the diligence of Transit Museum staff. They are made of wood with metal frames and were used exclusively on elevated lines, which were originally on Myrtle, Park, Lexington, and 5th Avenues and Fulton Street starting in the 1880s. Later lines acquired elevated sections under the Dual Contracts of 1911: but those lines had sections in tunnels, and wooden cars were enjoined from running in tunnels due to the fire risk.

There was an option to ride outside on el cars. I’m not entirely sure of the fare control logistics. I imagine there was a door on the way to the platform where you handed over your nickel and acquired a ticket, which would be taken onboard. In these “gate cars” passengers entered and exited through open-air vestibules at the front and back of each car and a conductor manually opened and closed metal gates and rang a ceiling-mounted bell when passengers were safely on board to signal the motorman to proceed.

Note how narrow the cars are; people were thinner in 1904. Seating was combination of two-seaters you see here, plus a section in each car with long benches facing across the aisle, the configuration employed in all modern subway cars of today. These seats were rattan also, in better shape than on the Standards.

The straps that “straphangers” in the el cars used were made of actual leather. In later subway cars they became porcelain, then metal, and are increasingly rare today.

Seats facing the windows, the only sensible way to ride a subway.

A look at the rattan seats of the Elevated car. Either the seats are very well preserved, or the rattan was replaced recently. The only good way to get interior shots was to remain in the car when one batch of merrymakers exited and before the next batch entered.

After leaving the Parade of Trains, I walked north into the heart of Brighton Beach, which boasts NYC’s largest community of Russian immigrants. The area was developed in the early 20th Century as a seaside community with large apartment buildings on the main streets interspersed with small, bungalow-like dwellings on the side streets. The bungalows are arranged in rows and are connected by a group of pedestrian walks and narrow streets navigable by motor buildings. To an outsider, the lanes can be confusing, since they are all numbered in a Brighton series of streets.

Above we see Brighton 3rd Lane emanating east from Brighton 3rd Street. A massive tree partially blocking the Lane’s way has been cut down.

If you look at a Google Maps section of the area, there’s something of a method to the madness. Many of these small laneways with their bungalows can be found between Neptune and Oceanview Avenues. North-south streets are called Brighton 1st, 2nd, 3rd, etc, with the laneways in between called Places. Meanwhile, east-west laneways are called Court, Walk, Lane, in that order. But other laneways named Terrace and Path seem to be wild cards.

Gradually, higher-rise buildings are edging out the bungalows. The area is not protected by NYC Landmarks. The peripatetic Nathan Kensinger noticed this trend as far back as 2010.

Well, if you’re new to Brighton Beach, this farrago of Brighton 2nd and Brighton 3rd this or that can be terribly confusing. Why on earth were the streets named like this?

Well, they weren’t, always. In the first couple of decades of the 20th Century, these lanes weren’t numbered, they all had names, such as Pine Court, Beech Court, Linden Court, Walnut Court. Easy enough names to remember, no? Take a look on this Belcher-Hyde atlas excerpt. Here’s a second one. You get the idea. The streets called Brighton 1, 2… 15 today used to be southern extensions of the East numbered system of streets (I’ll get into that a little later). The walkways and courts between the bungalows were all named, many quite easy to remember. As noted on this FNY page, there are a couple of leftover ones that didn’t get Brighton numbers.

My guess is that the city wanted to eliminate any chance that street names in the official record books, as well as Post Office records, would be duplicated. There were certainly no Brighton 1st Paths that were already on the maps.

With all good intentions in mind, sometimes it’s better to leave well enough alone.

Add a very small subset of “Banner” streets to the mix, as two dead ends, Banner 3rd Terrace and Banner 3rd Road, can be found on Brighton 3rd Street north of Neptune, with “Banner” and “Brighton” streets meeting up. The Banner streets are named for nearby Banner Avenue. Sergey Kadinsky wrote a September 2019 piece on this particular neck of the Brighton Beach woods.

Brooklyn is rife with ‘theme’ sets of streets; the two most-encompassing are the East and West numbered streets, but there are also Bay and Beach numbers, North and South numbers, and Plumb, Paerdegat and Flatlands numbers. I’m likely leaving some out. It’s a Brooklyn thing, as no other borough has so many subdivisions of numbered streets.

“No one here gets out alive.” Just kidding! Coney Island Hospital, at Ocean and Shore Parkways, became Brooklyn’s largest employer in 2011. The hospital was established in 1887 as a first aid station on Coney Island Beach. The buff brick building opened in 1910, with the modern white hospital building opening in 1954.

For a couple of blocks, I walked on the west side pedestrian path on Ocean Parkway. When renowned city planners Frederick Olmsted and Calvert Vaux built Ocean Parkway between 1874 and 1876, they envisioned a six-mile long extension of their earlier creation, Prospect Park, which some say is even better than their masterpiece, Central Park. When first laid out, Ocean Parkway was a direct route for pedestrians and mounted traffic, as well as buggies and wagons, to get to the Coney Island shore from Prospect Park. Even the bicycle wasn’t yet invented when the parkway first appeared.

These days, of course, Ocean Parkway is a pedal to the metal speedway, with synchronized stoplights. Occasionally you can hit the jackpot and never hit a red light while driving from the Belt Parkway to Prospect Park.

This walkway was originally laid out as a bridle path. According to the New York Times, the bridle path was paved over during 1970s renovations. Conceivably, it could be restored, as Kensington Stables is still in operation at the north end of the parkway on Caton Place and East 8th Street (though the Prospect Expressway makes getting from the stables to the path difficult).

Brighton Court, serving a mid-20th Century garden apartment complex east of Ocean Parkway south of Avenue Y. East-west “courts” are named in tandem here, with Manhattan Court paralleling Brighton Court, named for the two beaches east of Coney Island. Another pair is named, imaginatively, “Ocean Court” and “Parkway Court.” Another, Boulevard Court, was renamed Angela Drive in the 1980s for a local woman who died of leukemia.

Telephone pole at Avenue Y and East 1st Street. American flags became popular motifs on fire hydrants and telephone poles in NYC on two occasions: the first, the Bicentennial year of 1976 (the sestercentennial year of 2026 is now on the radar). The other, of course, was the 9/11/01 terrorist attack. I’d guess, from the faded paint, that this commemorates the former.

Despite NYC’s efforts to avoid duplicating street names in boroughs, there are two West Streets in Brooklyn. The first one parallels the waterfront in Greenpoint. This is the second, marking the divider between “East” and “West” sequences of numbered streets in what had been the town of Gravesend.

When Gravesend gained numbered streets in the late 1800s and early 1900s, the city of Brooklyn and then, New York in 1898 followed the Flatbush numbered streets system. Two sets of numbered streets were called “East” and “West” because they were located east or west of Gravesend Avenue, which had the Culver surface railway running along its length. In the late 1910s the Culver was placed on an elevated structure and in 1933, Gravesend Avenue became McDonald Avenue, for the chief clerk of Kings County’s Surrogate Court, John McDonald, who must have been a pleasant fellow for such a lengthy street to be named for him.

At Kings Highway, McDonald Avenue takes a turn to the southwest, but the numbered streets were laid out to not do that, and continue south. How to delineate the divider? I think there are some municipalities that actually have a “zero” street for such an occasion. Washington, DC has “Capitol Streets” that do the trick. In Brooklyn, it’s “West Street,” which makes no sense, as I can’t discern what it’s west of. After all, it’s east of the primary divider, McDonald Avenue.

This is the Edible Schoolyard project at PS 216:

Edible Schoolyard NYC’s mission is to support edible education for every child in New York City. We partner with New York City public schools to cultivate healthy students and communities through hands-on cooking and gardening education, transforming children’s relationship with food…

Established in 2010, Edible Schoolyard NYC is a nonprofit organization committed to bringing Alice Waters’ vision to New York City public schools. When Alice Waters, acclaimed restaurateur and food activist, created the Edible Schoolyard Project in Berkeley, California in 1995, she knew the best way to teach children the connections between food, health, and the environment was by integrating an edible education program into our schools’ everyday curriculum.

As the first official “Founding Edible Schoolyard” in the Northeast, Edible Schoolyard NYC has adapted the Edible Schoolyard Project curriculum and vision to fit the unique needs of New York City public school children. We are inspired by the Berkeley program and are an autonomous nonprofit dedicated to New York City. [Edible Schoolyard NYC]

PS 216, Avenue X between West and East 1st Streets, is named for Arturo Toscanini (1867-1957) the exacting conductor of NYC’s Metropolitan Opera, NY Philharmonic, and the NBC Orchestra.

The American Legion Marlboro Post #1437, at Avenue X between West 1st and 2nd Streets, along with the Marlboro Houses, is a remnant of the neighborhood’s former name.

The wedge of Gravesend below the “V” formed by Bay Parkway and 65th Street was once called Marlboro in an era when there were still major racetracks in the region. The development was founded by the Brooklyn Development Company in the early years of the 20th Century and followed the Brooklyn convention of “sophisticated” British-sounding names to impart gravitas. The name Marlboro survives in Marlboro Playground at West 11th Street and Avenue W, and the Marlboro Houses, between 86th Street and Avenue X and East 8th and 11th Streets.

For more lost neighborhoods, see this FNY page.

This group of mixed residences-storefronts in a group of attached brick buildings on Avenue X has a playful seashell motif at the roofline. We are about a mile north of the Coney Island beach at this point.

Stryker Street parallels McDonald Avenue, thus running athwart the street grid, from Village Road South to Avenue X. The Stryker family were early Dutch settlers in Gravesend (the name appears on this 1890 Kings County atlas) and a prominent Stryker, Francis Burdett Stryker, was a 3-term mayor of Brooklyn in the 1800s.

“Stryker” reminds me of Matt Striker, the former WWE wrestler who was originally a teacher in the NYC Department of Education at Benjamin Cardozo High School in Queens: unbeknownst to the DOE, Striker moonlighted as a wrestler. After leaving the DOE, Striker naturally worked a “heel” (rulebreaker) gimmick with the World Wrestling Federation.

At McDonald Avenue, Avenue X encounters the Culver El, serving the F train, as well as the brick entrance to the Coney Island Yards. Here also, McDonald Avenue changes its name to Shell Road. South of here, Shell Road, named for its original paving, was one of the first roads connecting Gravesend with the Coney Island waterfront. Here also, 86th Street runs in an absolutely straight direction to the Narrows in Bay Ridge.

An interesting perspective view featuring the Avenue X station platform and the station canopy.

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop, and as always, “comment…as you see fit.”

9/30/19