Although NYC divested most of its colonial-era “royal” names after defeating the British in the Revolutionary War, there are a few that doggedly hang on, such as Prince St. in Soho, Kings Highway in Brooklyn, and Fort Tryon Park in upper Manhattan, which was named for a British fort commemorating Sir William Tryon (1729-1788), the last British governor of the colonies. The city took title to the property, which was partly owned by the former Cornelius Billings estate, in 1917, and the large (67 acres) park was designed by Frederick Law Olmsted Jr. (son of the Central and Prospect Park developer) in 1935. There are highlights for even the most avowed non-naturalist such as your webmaster to enjoy here.

Fort Tryon Park is one of the two great parks of upper Manhattan island, the other is Inwood Hill Park (which still has caves where Native Americans resided, Manhattan’s last forest, and the spot where, according to many accounts, Peter Minuit “purchased” the island from the Lenape since the Lenape did not follow the concept of personal property to be bought and sold, they were unaware they were even selling the land).

Though I am planning to bring a tour into Fort Tryon Park, maybe in the 2020 season, I did not enter the park to scout around today. The weather was a bit dull the day I was here and what sun we had was low in December, and I’d rather explore the hills (its hills have never been leveled) and get shots on a better day. Instead, I decided to explore the streets just to the park’s east, east of Broadway (Fort Tryon Park’s eastern boundary) north of about West 190th and south of Dyckman.

GOOGLE MAP: FORT TRYON AREA WALK

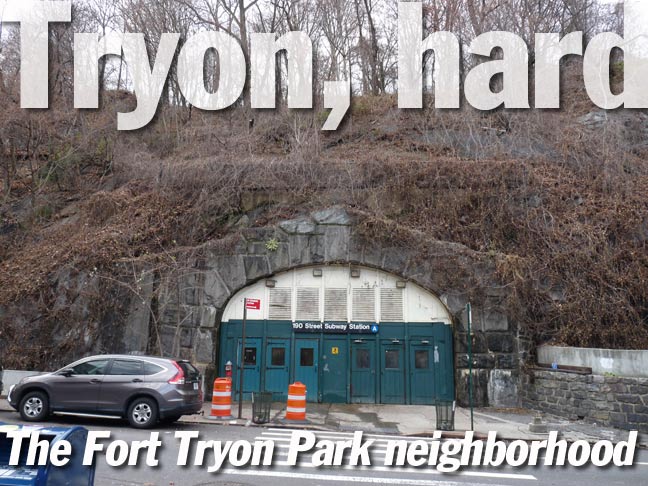

I took the A train to almost the end of the line, the 190th Street station. Note the cylindrical shape of the tunnel. As a rule, when you look into a subway tunnel from the station platform, the edges have been beveled off so the opening looks like a rectangle. However, there are some stations that have an arched entrance such as here; another one is the Court Street BMT station serving R trains.

Because of the hilly uptown topography, both IND stations (like this) and IRT stations have unusual layouts. Both the 181st and 190th Street stations are deep and the 190th Street station requires a (wo)manned elevator to access. In addition at 181st and 190th, a platform has been built above the tracks with staircases accessing the platforms. On the platforms themselves, there are masonry arches along the walls that forced IND designer Squire Vickers to place much smaller station ID signage consisting of a single number.

Fort Tryon Park is the home of The Cloisters, a branch of the Metropolitan Museum of Art specializing in medieval art and assembled by John D. Rockefeller Junior in 1938.

Most IND stations built from 1932-1940 or so are fairly uniform, with large underground mezzanines and of course platforms with a uniform design scheme. However some uptown IND stations got a bit playful with the entrances. 190th Street, for example, actually has a headhouse. Some of it is given over to transformer equipment, but some of it is a foyer leading to the elevators. The doorways are standard IND design for these kind of stations. You can also see a boarded-up protuberance that used to be a token window, one of the few such survivors still to be found in the subways.

This is a small playground area just east of the headhouse. From it a series of ramps leads deeper into Fort Tryon Park, some of which has views of eastern Manhattan and the Bronx beyond it.

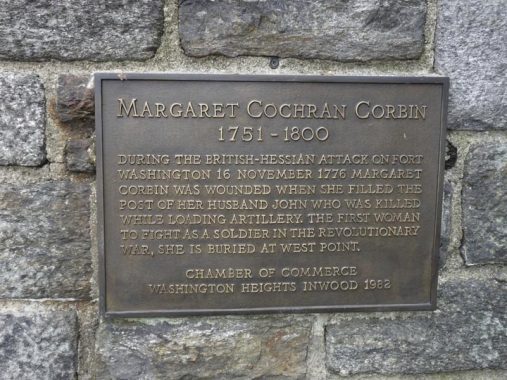

Returning to Fort Washington Avenue at the entrance to Fort Tryon Park, there’s a plaque commemorating a female combatant in the Revolutionary War. Margaret Corbin Drive, which runs through the park and carries traffic to The Cloisters, was named for a woman who “manned” a cannon after her husband was shot during a battle in the war for independence.

There are some lamp stanchion survivors on the Fort Washington Avenue side of the 190th Street station. These full size stanchions used to be a lot more common but this seems to be the only one remaining in the city. I’m surprised the MTA hasn’t removed it because of their nonending quest for station ID uniformity. Today there’s an illuminated green globe indicating the entrance is open 24/7, but formerly there were incandescent bulbs lighting up the cutout “SUBWAY.” It’s just waiting for a delivery truck to make quick work of it, but it’s made it now for nearly 90 years.

In addition, there’s this amazing set of IND-style lighting stanchions lining the ramp between Fort Washington Avenue and the station headhouse. Again this is the only station in the subway system that sports these. They give an intriguing look at what IND elevated stations’ platform lighting may have resembled, if the IND Second system, which included some elevated stations, had ever been built. To me they definitely look weird, with cowls that make them look like Martians. Some of them still have greenish-white mercury bulbs. They are well-protected by fencing.

A lengthy tunnel leads from the 190th Street mezzanine east to Bennett Avenue, where another set of IND doors at the east edge of Fort Tryon Park at the bottom of the hill allows an exit. Later in this walk i saw another subway entrance tunnel that looks considerably different.

Bennett Avenue from the subway entrance north to Broadway borders on some of the biggest schist rock outcroppings in the city. These bedrocks may have been exposed by a retreating glacier some 10-12,000 years ago.

The avenue is named for New York Herald founder James Gordon Bennett, who had holdings in upper Manhattan. Herald Square was named for the newspaper, whose offices were at 6th Avenue where it meets West 35th Street and Broadway. The paper merged with the New York Tribune in 1924, and the New York Herald Tribune went out of business in 1966.

I wandered north of Broadway into the streets that make up the immediate neighborhood. I like to call it Fort Tryon but it’s actually the southern end of Inwood. Broadway here is part of the colonial-era Kingsbridge Road, named for the bridge that carried it across Spuyten Duyvil Creek to the mainland. Here, the street turns in a definite northeast direction and therefore, the street grid is oriented in a NW to SE direction. Maybe because of that, the streets that were laid out here from 1890-1920 were allowed to keep their old names, with just a few numbered streets in the vicinity.

One of them is West 196th, which takes a bent route from Broadway to Ellwood Street. Its chief occupant is Intermediate School 218, which boasts an artificial turf running track. An art project produced a handy dandy guide to US state capitals.

A pair of apartment buildings on Nagle, one from about 1910 and a Moderne building likely from 1930. No chroniclers can account for the name of Ellwood Street; the place name Ellwood is a short form of “Elderwood” so there may have been elder trees in this neck of the woods at one time. Or, Ellwood Blues, perhaps.

Bogardus Place runs one block from Ellwood to curving Hillside Avenue. It’s somewhat run of the mill and lined with apartment buildings, but it’s named unusually. The name “Bogardus” is known in NYC lore for archiect/designer James Bogardus, who designed the first cast-iron front buildings in Manhattan in the 1840s. But they were in the Financial District, Tribeca and SoHo, not this far north. The answer lies in the Bogardus family holdings in the Fort Tryon area when streets were laid out.

Looking toward the Cloisters at Ellwood and Hillside Avenue. The rear of Hillside Avenue looks like parkland, but the pitch is too steep to really build much, and the plot remains empty.

The Met Cloisters, which opened to the public in 1938, is the branch of The Metropolitan Museum of Art devoted to the art and architecture of medieval Europe. Located in Fort Tryon Park in northern Manhattan, on a spectacular four-acre lot overlooking the Hudson River, the modern museum building is not a copy of any specific medieval structure but is rather an ensemble informed by a selection of historical precedents, with a deliberate combination of ecclesiastical and secular spaces arranged in chronological order. Elements from medieval cloisters—Saint-Michel-de-Cuxa, Saint-Guilhem-le-Désert, Trie-sur-Baïse, Froville, and elements once thought to have come from Bonnefont-en-Comminges—and from other sites in Europe have been incorporated into the fabric of the building. [Metropolitan Museum]

I’ve called the Bronx the Borough of Apartments, but northern Manhattan can make a claim too. Take a good look at these fantastical designs along Arden Street between Nagle and Sherman Avenues.

As late as 1891, streets such as Arden, Sickles, Thayer and Ellwood were nameless lines on maps. Check out this atlas plate.

The intersection of Arden Street and Dongan Place is unchronicled in the NYC guidebooks (but that’s why you’re reading this). The Roman Catholic Our Lady Queen of Martyrs Church was dedicated in 1928 [Gustave Steinback, arch.] The parish grade school, self contained with the church, was added in 1950. This is one of those Catholic school/church combinations; I recently found another, St. Joseph Patron, on Suydam Street in Bushwick. My own childhood parish, St. Anselm in Bay Ridge, has such a combination from the parish’s inception in 1922 until 1953, when the present separate church was consecrated.

Dongan Place, one block between Arden Street and Broadway, has a bend in it much like East 196th Street. Irish Catholic Thomas Dongan (1634-1715) was appointed governor of New York by the Duke of York in 1682 and remained at that post until 1689. His tenure was marked by religious toleration, rare in that era; his family had to move to France when he was a boy when Oliver Cromwell’s forces overthrew and executed Charles I in 1649, and perhaps Dongan was sensitive to the persecution of faiths other than the Church of England. He became 2nd Earl of Limerick in 1698. As part of his appointment he was granted 5100 acres in what is now Dongan Hills, Staten Island, which he later expanded to 25,000 acres.

Dongan’s place in NYC history was solidified when he gave the nascent New York it’s first charter, divided the city into wards and founded the Common Council, the first-ever representative assembly in New York history, whose descendant is the current City Council.

Steep staircases and paths leading to The Cloisters, and more schist outcroppings, can be found at the northeast end of Fort Tryon Park at Riverside Drive. Indeed, mounting the steps in this park will raise your heart rate and eliminate the extra poundage pretty effectively. However, I don’t live in these parts.

While some parts of New York City are park-starved, such as Sunnyside, Queens, denizens of northern Manhattan have both Fort Tryon and Inwood Hill Parks — each among the largest in NYC — to choose from.

Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormon) Church at Riverside Drive and Payson Avenue. Though the Mormon Church seems to be associated with the public imagination as centered in the western states, the faith was founded by Joseph Smith in western New York State. The faith breaks from other sects of Christianity in many ways, most importantly, it holds that God the Father and the Son are separate persons; for this reason, the Mormon Church is called non-Trinitarian.

Payson Avenue is named for Rev. George Shipman Payson, the pastor of Mount Washington Presbyterian Church at West 204th Street and Sherman Avenue from 1874 to 1920. The church served early families of Inwood, including the Dyckmans, the Ishams and the Vermilyeas, whose names appear on other street signs. George Shipman Payson was a relative of Charles Shipman Payson, who owned the New York Mets after the death of his wife Joan Whitney, selling the team to Nelson Doubleday and partner Fred Wilpon in 1980.

A look at Riverside Drive’s northern end, approaching Broadway at Dyckman Street. It’s one of the longest continuous streets in Manhattan, exceeded by Broadway, Amsterdam and 1st through 3rd Avenues. Along with bordering Riverside Park, it was built in stages beginning in the mid-19th Century. In 1891, the northern end was mapped as Public Drive but not yet built. In the 1930s it was joined along the Hudson by the Henry Hudson Parkway.

A pair of one block streets. Staff and Henshaw, run between Riverside Drive and Dyckman Street. When first laid out they, as well as Payson Avenue, were called A, B and C Streets. Both were named for neighborhood combatants killed during World War I.

The Packard showroom at Broadway and Sherman Avenue, across the street from Fort Tryon Park, was designed in 1926 by architect Albert Kahn, who designed Packard showrooms across the country and, although he is now little-known, was in his day one of the highest compensated architects. Packard, famed in its early years for luxury autos, was in business from 1899-1954.

The company was founded by James Ward Packard, brother William D. Packard and their business partner George Louis Weiss, in Warren Ohio. Packard was marketed as luxury brand until World War II, but hoping to gain a greater share of the market, started making more affordable models after the war. Ultimately it was unable to compete with automotive leaders Ford, Chrysler and GM. The company merged with Studebaker in 1954 — which was also out of business by 1966.

Fittingly enough the Packard showroom in Inwood is now a parking garage.

Another Kahn Packard showroom bearing terra cotta letter P’s on the outside walls can also be found on Northern Boulevard between 45th and 46th Streets in Long Island City, an area still home to numerous car dealerships.

The building formerly featured a large PACKARD sign though I’m not sure it was neon, as seen in this 1940 tax photo.

A block east of Broadway itself between West 193rd Street and Fairview Avenue runs a one block street, lined with apartment buildings, called Broadway Terrace. Besides Broadway, there are a number of streets in NYC with Broadway in their names: East Broadway, West Broadway, Old Broadway, Broadway Alley, and Broadway Terrace.

All of them seek to bask in Broadway’s fame.

Both Broadway Terrace and Fairview Avenue traverse steep hills and bordering apartment buildings, fronting on nearby Wadsworth Terrace, depend on massive superstructures. The building shown in the “V” formed by Broadway Terrace and Fairview is among the most photographed in this part of Manhattan.

Painted sign at Broadway and Fairview. Would you get a CAT scan at a place that advertises witha crude handlettered sign?

Here’s an entrance to the IRT 191st Street station at Broadway. The subway actually runs below St. Nicholas Avenue, a good three streets to the east, and so a very lengthy tunnel was built to connect the station to Broadway. The station is the deepest in the entire subway system at about 180 feet down. Though most of the IRT subway reached these parts in 1906, the 191st Street station is a latecomer as it was constructed in 1911.

Here’s something wild I found out about the 191st Street station that is referenced nowhere else but in NYC Subways:

On the southbound platform there is a room formed by corrugated metal labeled “trash room”, but formerly was, believe it or not, an astronomical observatory of sorts. The instruments once in this shed were an experiment by New York University to capture cosmic rays from the stars. Cosmic rays are the nuclei of metal elements, the very atoms without the electrons, expelled at nearly light speed from certain kinds of star. Their mass and speed give them very high energy, enough to penetrate all the solid rock above the platform. The idea of building this special observatory here was to prevent the terrestrial radiation from interfering with the collection of the cosmic rays. The rock blocks most of the terrestrial signals which come from the street, letting the extra strong rays from the stars to pass through without contamination.

I didn’t venture too far into the station to get the full effect, but the 191st Street tunnel access is quite different from the 190th Street, shown above, by the simple fact that it’s totally covered with street art and graffiti. The city actually commissioned the art in 2015. More of the art can be seen at NYC Subway.

I was fascinated by the massive storage warehouse at #4396 Broadway, near West 187th, bearing “Sofia Storage” signage; a neon sign was recently removed. At the building’s rooftop are bas reliefs of Men At Work. A 1940 tax photo reveals that back then, Sofia Brothers owned the building.

[T]he origins of Sofia Bros. were in the Bronx. In 1900 Theodore Sofia and his wife, Theresa Sofia, lived at 1221 Intervale Ave., the Bronx. They were immigrants from Italy (Theodore in 1879 and Theresa in 1883), and they had eight children ranging in age from 15 years to 4 months, all born in New York. Theodore worked as a street sweeper for the New York City Dept. of Public Works. By 1910 Theodore Sofia had died, and his widow, Theresa Sofia, still lived at 1221 Intervale Ave. The family maintained a boarding and livery stable at this address. This stable was the origin of the Sofia Bros. moving and storage business. The brothers in the business were Charles Anthony Sofia (1885-1962), Frank Sofia (1886-1937), Patrick Sofia (1890-1966), James John Sofia (1892-?), Theodore Charles Sofia (1895-1955), and John Sofia (1899-1985). Mater Familias was Theresa Sofia (1857-1941). In the 1910 U. S. Census all of the boys were working in the stable except John, who was only 10 years old. Much more at the Indispensable Walter Grutchfield’s page

Time to finish up the day’s festivities. I decided to board the A train at the 181st Street entrance at Overlook Terrace, which actually should be called Underlook Terrace; it’s at the bottom of a steep hill. The entrance, which boasts MTA signage from the 1940s and the 1980s, opens to another lengthy tunnel to the fare control, which is unmarked by street artists.

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop, and as always, “comment…as you see fit.”

1/25/20

17 comments

A tour of Fort Tryon Park would be amazing!!!!

A great rendering of the neighborhood I grew up in. One note of correction, though: Manhattan schist is bedrock and was not deposited by glacial action.

The Packard building (4660 Broadway) was a NYCHRA welfare center from the late 1960’s until about 2007.

James Gordon Bennett was an ordinary enough person, but his son James Gordon Bennett Jr. (called Gordon Bennett to distinguish himself from Dad) was quite the character. He was a fast-living playboy long before the term actually existed. He had to run the Herald from France for many years after having to flee the US following a major scandal; he had arrived drunk for a big reception in his fiancee’s family mansion and in front of everyone Drained the Weasel into either the fireplace or the grand piano (accounts differ). I’m actually hoping it was the grand piano, as that would have been funnier. In 1879 Gordon bankrolled an Arctic exploration by the ship USS Jeannette. It was a catastrophe, with the ship locked in the ice for almost two years before breaking apart. A third of the crewmen drowned, another third reached land but starved to death, and the remaining third survived after Siberian natives rescued them.

No Kevin,

The Schist outcrop on Bennet Ave was not deposited by a retreating glacier. The Manhattan Schist formation is one of the three formations that underlay most of Manhattan and the Bronx. It is a metamorphic rock formed hundreds of years ago. It may have been exposed by the glacier’s motion “bulldozing” any sedimentary overburden, but it is very much “in situe.”

Correction: formed hundreds of millions of years ago not hundreds of years ago.

I hear that if you show pictures of Fort Tryon Park itself and without anything that surrounds it, you could almost think that you weren’t even in Manhattan for a moment, and the same my apply for Inwood Hill Park and possibly some sections of Central Park as well..

I lived on Bogardus Place for a couple years about a decade ago, while in grad school at CCNY. Prior to that, I hadn’t even realized there was so much of Manhattan north of Harlem. It has some sketchy areas, for sure, but also many interesting and lovely locations. Thanks for showing some of the highlights!

I had worked in the fort tryon 190 st train station more than 20 years. ago.Upstairs in one of the rooms I found some interesting tile work. the tiles on the floor had what appears to be Swastika inlaid into the tiles.

I believe these stations were built in the nineteen thirties so I was not sure if it pertained to the German Swastika or the original meaning of a religious symbol.I did not have a camera at the time so i never got any photos.

I lived on 191 street not pictured which also has a curve and was 1 block long from Broadway

A very interesting posting which inspired me to visit the deepest recess of the walk-in closet in my master bedroom to exhume the photo album which my wife reconstructed for me several years ago. It contains four black & white photos I took of a May,1963 family visit to The Cloisters which includes a great view of the Hudson River & the Henry Hudson Parkway. Too bad that in my youth I succumbed to false economy & didn’t buy Kodachrome.

Now, I have a question for you: Photo # P1450192 – Looking through the gate there appears to be a female in a seated position. Is she a statue or a solitary tourist who was inspired to meditate on the natural beauty of the place? Your planned tour sound like great outing.

Just a correction it is WEST 196 Street off Ellwood not EAST )( that would be in the Bronx)

The two dark brown buildings listed as Ellwood street Are actually on Nagle Avenue. The yellow brick building is on the corner of Nagle and Ellwood. There are some great Art Deco buildings in the neighborhood too.

I loved seeing this. I grew up on Dongan late 50’s-early 80’s. I never knew the building used to be a Packard show room. When I was little, it was a bowling alley and neighbors complained about the noise. Then it was the Welfare center.

I lived growing up by Ft. Tryon Park.

It was always so beautiful different times of the year

https://www.metmuseum.org/blogs/in-circulation/2018/fort-tryon-park-albums?fbclid=IwAR11CKb3wDE6sKNzy2ggC_RBL9BsrP53bg61j3yQT0BrSNzI0lzKRJUhBrk

https://libmma.contentdm.oclc.org/digital/collection/p15324coll6/id/466/rec/1

Kevin, some interesting sites about the assembly of Ft Tryaon and the Cloister

Excellent detailed summary!

The greatest bargain in public transportation was the M-4 Madison Avenue bus route which trailed up Fifth Avenue past many historic neighborhoods and terminated at the Cloisters.

A true favorite trip by a former New Yorker.

Thank You, Elaine Harmon in Texas

Regarding the old church-school combinations, there are, or were, quite a few of those around. St Gregory the Great, on West 90th Street, and St Gabriel’s, on 235th in Spuyten Duyvil, are two more. In recent years, however, the Archdiocese has “merged” both parishes — St Gregory with Holy Name on 96th, St Gabriel’s with St Margaret of Cortona — and closed both schools.