Continuing my Manhattan cross streets series. I’ve done them piecemeal in the past, but I’ve already posted 20th Street, 22nd Street and 17th Street in this batch, and 14th Street as well in autumn 2019 with more to follow. Today’s entry: 10th Street. I’ll have to split it into Parts 1 and 2, since 10th is the lengthiest one so far.

Before the Great Infection, I spent a number of Saturdays (and some Sundays too) crisscrossing Manhattan via its numbered streets. Over the years, I’ve done this quite a few times and I was amazed at how much stuff I missed and how much material I knew about and posted here and there, but never really formalized or categorized. Eventually I might make these “crosstown” posts their own separate category. I’ve already posted much of 11th, 12th, 13th, and 14th (twice) and before I get tired of this, I might just do every one of NYC’s numbered crosstown streets, since I had so much fun finding things I never knew about and revisiting things that I did.

After I finish the streets I walked during this time, I’ll add a strip link to all those pages.

A word about the Great Infection. So far I’m more concerned about what it’s done to my investments (which are modest to begin with) but in mid-March, I was admonished to stay indoors after my Facebook photo posts of meandering around Woodside and Sunnyside were seen. Just to be on the safe side, I’ll have to confine myself close to home the next few weeks (months, maybe), whether or not I get ill. I hope everything’s back to normal—healthily and financially—before too much longer! As of April 18th, I remain Covid-free.

The west end of West 10th Street, the part that runs SW to NE in Greenwich Village between West Street and 6th Avenue, was called Amos Street until the mid-1800s.

This street was originally named for Richard Amos,who owned a parcel of land formerly belonging to the vast estate of Sir Peter Warren, which stretched from Christopher Street north to 21st Street west and north of what would become Washington Square Park.

It is thought that Christopher and Charles Streets are named for Richard’s relative and trustee of the Warren Estate named Charles Christopher Amos. But the streets didn’t go in that order…from south to north, the names went: Christopher, Amos, Charles. West 11th and 12th Streets had been named Hammond and Troy Streets, but surveyors decided to make those streets western extensions of the numbered grid.

The former Holland Hotel, with its circular corner turret, looks much the same today as it did when it was built in 1904, a Renaissance-inspired building designed by architect Charles Stegmayer. The ornate column at the entrance can be fond on many older NYC buildings from the same period. The hotel contained 38 small rooms and catered to dockworkers, seamen and stevedores working the busy Hudson River docks of that era.

Just across the street at the Amos Dock (West 10th was named Amos Street until the mid-19th Century) John “Old Smoke” Morrissey had fought Know-Nothings gang leader Bill (The Butcher) Poole to a draw on July 26, 1854, seriously wounding both men. Later, Morrissey’s friends shot Poole dead. Reportedly his last words were, “Goodbye boys, I die a true American.” Poole, a respected figure in the anti-Catholic gang wars and a major political operative of the era, was sent off in a grand funeral, the procession attended by thousands. He was interred in Green-Wood Cemetery and was given a marker there about 15 years ago.

In 1910, the hotel had new ownership and was renamed the Clyde. This far west, it couldn’t hope to obtain much of a respectable clientele. In the 1970s, it was home to Peter Rabbit, a gay bar; presently the bistro Uguale (Italian for “Equal”) occupies the ground floor. I’m not sure, but I imagine the upper floors are rental apartments these days.

Just east of West (how’s that for a phrase) West 10th Street encounters a tiny alley in a borough that has relatively few of them, Weehawken Street.

The short lane, which runs between Christopher and West 10th Streets just east of West Street, stands on what, in the colonial era, was on the grounds of the Newgate State Prison. Nearby Charles Lane is a Belgian-blocked alley that used to run along the prison’s north wall:

Newgate Prison [stood] in the West Village between 1797 and about 1828 at the Hudson River shoreline, bordered by Washington, Christopher and just south of where Perry Street would later appear. Newgate was NY State’s first penitentiary, and pioneered radical correctional policies such as allowing prisoners light in their cells, water to bathe, no corporal punishment, visits from families, and rehabilitational training. By the late 1820s, the prison was no longer isolated and was surrounded by streets and businesses, and transferred to Ossining in Westchester County, the prison known popularly as Sing Sing (land on which the prison was built was called Sintsink by the Indians).

After Newgate’s prisoners were transferred to Sing Sing, NYC reserved the waterfront area between Christopher and Amos (later West 10th) for a public market. Weehawken Street owes its existence to this market, as it was laid out around 1830 to accommodate wagons bringing produce to and from the market, serving the small wholesalers built along its length. Christopher Street was also widened in this area to accommodate the market. Farmers from New Jersey locations — prominently, Weehawken — set up stalls in the market.

By some accounts “Weehawken” is derived from a Lenape Indian phrase meaning “rocks that look like trees.” The street has its own Landmarked District, perhaps NYC’s wee-est.

The 2nd oldest building on Weehawken Street also fronts on West Street and is known as both #8 Weehawken and #392-392 West Street. By many accounts it is the only building left over from the old Weehawken Market and one of the few wood-frame buildings left in Manhattan. It had been in a row of similar buildings that had all been demolished by 1937. I discuss it further at FNY’s Weehawken Street page.

The southeast corner building at #304 West 10th and Weehawken Street is actually among the younger buildings in the area. It was constructed in 1873 for brick manufacturer Charles Schultz as a tenement housing eight families and a store. By 1896 the ground floor was occupied by a saloon called the Plug Hat, and into the 20th Century the house was owned by brewers and saloon keepers. In 1961 the last saloon moved out and the ground floor was converted to a laundry.

The building rates not one, but two, plaques with historic information!

Before about 2011, a parking garage supported this Type G wall lamp that had been landmarked (likely after 1994, as it does not appear in the 1994 Landmarks Preservation Commission pamphlet listing landmarked lampposts). When condo building 303 West 10th was built, the bracket was removed and replaced on the new building when it was completed.

The residential building at 667 Washington Street, NE corner of West 10th, was constructed as The Shepherd Warehouse in 1894.

A remnant of a time when beasts of burden were the primary means of transport. The building on the NW corner of Greenwich and West 10th bears several stable signs and a pulley for hay bales at the roofline.

On the West 10th Street side, more faded signs hint that they were placed there at a time of transition from ole Dobbin to motorized transport. Based on old photos I’ve seen that would date this sign to the early 1920s, though horses were still seen pulling wagons well into mid-century, and of course the NYPD has always had a mounted division. A painted ad on the side of the building is nearly illegible. I make out the word “boarding” but not much else.

According to a Greenwich Village Historic District designation report, the building dates to 1911 and there was a trucking business here until 1921. Interestingly, actor Wesley Snipes owned the building from 1998-2000.

The Bishop Crook at the NE corner of Greenwich and West 10th Street goes back to perhaps the 1920s and while design-wise it’s identical to retro versions being installed today, it can be differentiated because of its rust and also the lack of a garland encircling the shaft, which modern Crooks have. It also has a long-disused bracket for street signs. I’ve covered this lamppost extensively in FNY before.

Since an elevated train ran along Greenwich Street until 1940, this post may be only that old. Had it been older it would have been a Dwarf post, just tall enough to fit under the el (unless the el was high enough off the ground to fit a regular size Crook.

519 Hudson, NW corner of West 10th, hosts the famed kitsch restaurant/bar Cowgirl Hall of Fame (since recently known as just Cowgirl—there’s an actual Cowgirls Museum and Hall of Fame in Fort Worth, Texas. In 1940, it was a tire shop.

518 Hudson, SE corner of West 10th, is one of a row of brick townhouses built by developer Isaac Hatfield in 1827.

Pulling back to view the apartment house row (known elsewhere as a “block”) 519-525 Hudson Street at West 10th. Its corner turret and midblock pediments are still intact and the building has a plethora of ornamentation and detail not approached by today’s architects. The building rose in 1889.

#228, 230, 232 West 10th, between Hudson and Bleecker. #228 is newer (1877) while the two others go back to the mid-1830s. #230, in the middle, is a former stable; they are usually recognizable by wide entrances.

A nice pair, #224 and 226, built in 1847, once had a deceased member of the triplets, #228. #226 comes closest to the building’s original appearance.

#350 Bleecker, at the NW corner of West 10th, was once home to Kim’s Video West, one of an informal area chain which had, some say, the best selection of VHS tapes (remember them?) in the city, complete with an eccentric owner. Employees over the years at various Kim’s included Albert Hammond Jr. of the Strokes, rocker Andrew W.K. and rock writer turned theologian Dawn Eden Goldstein.

#198-200-202 West 10th between Bleecker and West 4th, built in 1829 and 1839.

This 5-story apartment house, The Warwick, was built in 1881. Affixed to the West 10th Street side is a “humpback” street sign, used in NYC streets from the 1910s-1960s. The improbable meeting of West 4th and 10th Streets was created when the city decided to number both streets, which previously carried names.

West 4th turns northwest at 6th Avenue and intersects 10th, 11th, 12th and 13th. The short story is that long ago, an asylum stood on the street when it was called Asylum Street, and when the asylum was torn down in 1833, the city decided to make it a western extension of West 4th, creating illogical intersections when the other named streets also acquired numbers.

I have never been inside Fedora, on West 4th northwest of West 10th, but have been aware of it for many years because of its iconic neon sign, which lights up at night (“bar” in red, “Fedora” in green). I was unaware, all those years, that it wasn’t named for the hat, but for its now-former owner, Fedora Dorato, who had run the small basement Italian restaurant/tavern for sixty years.

Fedora Dorato came with her family from Florence in 1931 when she was 10. She has lived upstairs from the restaurant named for her since she married Henry Dorato in a building that Henry’s father bought in 1921, where he ran the restaurant speakeasy Charlie’s Garden. Except for paint jobs and air conditioning, the place has remained the same, with its pressed-metal ceiling, intimate tables and dedicated waiters. The Villager

Restaurateur Gabriel Stulman took over the space and has “reimagined” it as “a casual supper club” according to Grub Street. Fedora spoke in favor of Stulman’s plan to the community board, which approved. She passed away in 2011.

There’s a handy dandy painted street map of the Village on the sliver of West 10th between West 4th Street and 6th Avenue.

Originally, 181 West 10th Street was a townhouse that was midblock between Waverly Place and West 4th, actually a bit closer to West 4th. Since 1914, it has been on the corner of 7th Avenue South, which was built south from Greenwich Avenue when the IRT subway was constructed. A new building that somewhat resembles it, 130 7th Avenue South, has been constructed to its right in this photo.

Can a parking garage be landmarked? Sure, when it’s in the Greenwich Village landmarked district. #160-168 West 10th, east of 7AS, was constructed in 1892 as a stable used by Henry Hilton and later adapted as a garage holding delivery trucks for Wanamaker’s, the former grand emporium on Broadway and East 9th Street.

In early 2020, Three Lives & Co. Books, SW corner of Waverly Place and West 10th, was shrouded in construction netting as its building was undergoing renovations. Long a Village favorite, the store takes its name from Gertrude Stein’s first book (1909) concerning three women living in the fictional town of Bridgepoint.

One of the greatest bookstores on the face of the Earth. Every single person who works there is incredibly knowledgeable and well read and full of soul. You can walk in and ask anybody, really, what they’ve read lately and they’ll tell you something — very likely something you’ve never heard of. [But] it’s always going to be something interesting and fabulous. I go there when I’m feeling depressed and discouraged, and I always feel rejuvenated. —Pulitzer winner Michael Cunningham

Continuing east on West 10th, the approaching tower of the Jefferson Market Library is so nice, I shot it thrice. Originally a courthouse, the building was constructed beginning in 1874 in what architects call Ruskinian Gothic (the Memorial Hall on the Harvard U. campus in Cambridge, MA is the same style) and was inspired by Ludwig II’s Bavarian castle, Neuschwanstein. Ludwig built three magnificent castles; he later went insane and was found drowned.

Come for the stucco, stay for the history, at Julius on the NW corner of Waverly and West 10th. Fats Waller and other jazz greats played here during Prohibition and it later became one of NYC’s first bars catering to a gay clientele, frequented by Truman Capote, Tennessee Williams and Rudolf Nureyev. It was the site of a sit-in by gays after they were refused service in 1966, foreshadowing the Stonewall riots, which were less polite.

“Artisanal” is a word you will see frequently in certain parts of town; it’s simply a 2-dollar word for “homemade.” At first I thought this place was named for the guitar player and composer in the Dutch group The Shocking Blue, Robbie Van Leeuwen, but that was 50 years ago. Actually this is an “artisanal” ice cream palace on the SE corner of West 10th and Waverly, that has other branches in Greenpoint and Cobble Hill, and they also sell from roving trucks owned by Ben and Pete Van Leeuwen.

Since 2017 I have been laying off sweets and bicycling more, which shaved 15-20 pounds, but I have to keep at it, so artisanal ice cream, or plain Sealtest, is restricted to a couple times per year.

Slotted in on lower Manhattan side streets are occasional Federal style townhouses that are the oldest residences of all, such as #139 West 10th, between Waverly Place and Greenwich Avenue. It was constructed in 1834 and is the one remaining from an entire row of identical buildings.

I have to make a confession. I like old firehouses around town simply because I enjoy seeing liberal use of the color red. Engine 18, a Romanesque building, designed by N. LeBrun & Sons, opened in 1891.

Out of the picture on the immediate left, at #130, in 1941-42 was known as the Almanac House, where Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger held hootenannies when they were in the Almanac Singers, a pro-labor, anti-fascist folk group. The Almanacs were so called because Lee Hays (who later had pop success with Seeger in The Weavers) said that back home in Arkansas they had two books in the house, the Bible for the next life and an almanac for this one.

Next door, #134-136 has its date of construction, 1874, conveniently inscribed on the pediment. It has served as a stable, then a garage in the past, and is now totally residential (a pair of storefronts are presently unoccupied). The large pair of windows on the third floor left side was once a hay loft.

Upon reaching the corner of Greenwich Avenue, I poked my nose around the corner and found this interesting Quality Meats sidewalk sign. I liked its white and silver esthetic, and its use of Futura, or something close. Futura was developed in Germany in the 1920s and was the first universal sanserif font before Helvetica became de rigueur in the 1960s.

Nearby was a delivery truck for La Frieda Meats, which is accepted as a mark of quality, but I had a La Frieda steak sandwich at Citifield in 2019 and found it rather tough; maybe my expectations were raised too high for ballpark eats.

Greenwich Avenue is one of the oldest routes in lower Manhattan; in the colonial era it was called Monument Lane since at its 8th Avenue end was a monument to British Major General James Wolfe (1727-1759) who had died in the Battle of Quebec in the Seven Years’ War, but by 1773, before American independence was declared, the monument had disappeared from local maps.

The St. Germaine Apartments, NW corner West 10th and Greenwich Avenue in white brick, makes a startling appearance in full sun.

This building, constructed in 1962, always reminds me of Lou Reed’s song from 1972’s Transformer, “I’m So Free,” which contains the lines:

“Oh please, Saint Germaine

I have come this way

Do you remember the shape I was in

I had horns and fins”

What was Reed referring to? A couple of sources say it was the Count of Saint-Germaine (1712-1784) a prominent composer, mystic, occultist and what would, by the 1960s, be referred to as a counterculturist. Perhaps, St-Germain liqueur. Maybe the actual Saint Germaine, a 5th-Century Gallic bishop, or a second Sainte-Germaine, a pious shepherdess. Or, perhaps, Reed was referring to this building, since he was a NYC resident beginning in 1964 after graduating from Syracuse.

Patchin Place, on West 10th between Greenwich and 6th Avenues, was named for surveyor Aaron Patchin. The presence of these two short cul de sacs in Greenwich Village (along with Milligan Place, around the corner on 6th Avenue) is a near-miracle, since over the centuries Manhattan has filled in most of its dead ends with buildings shoehorned into the spaces, which were worthless without anything making money on them. Check out Gil Tauber’s invaluable website Old Streets of New York to find out just how many defunct streets there are in NYC; Kenneth H. Dunshee’s As You Pass By, written to commemorate Manhattan’s old fire companies but also works as a historical tome about the city itself, contains a voluminous index to Manhattan’s vanished dead ends. It was recently reissued.

Though Patchin Place is home to one of two of NYC’s former public gas lamps (it was wired for electricity and is at the far end) the corner was also home to a scroll-less type 1 BC bishop crook post for several decades. In the 1990s, the post, which was landmarked and so could not be discarded, was placed in Jefferson Market Garden across the street. Ironically, it was replaced by a retro version of a Type 24 bishop crook.

See NYC’s landmarked lampposts on this FNY page.

Showing here the back of the Jefferson Market Library, which has done duty as a courthouse, women’s prison, and library since its construction in 1873 (it replaced a wood fire tower, which was used to call firefighters in the era before centralized fire alarms). As various buildings surrounding it were torn down, a public garden with restricted access (only open during certain times) was established to its rear facing Greenwich Avenue.

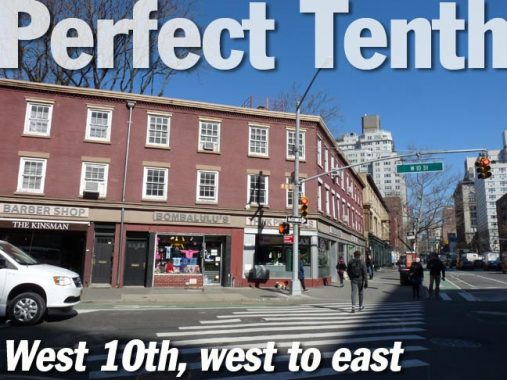

West 10th Street where it meets 6th Avenue. This is formerly where Amos Street began its western journey; east of here was West 10th. When Amos became part of West 10th, its houses were numbered to continue West 10th’s. The handsome mixed-use brick buildings on an angle were constructed in 1836.

The Jefferson Market complex of food stores on 6th Avenue between West 10th and 11th Streets is now mostly defunct; the Balducci’s flasgship gourmet deli closed here in 2003. The original Jefferson Market, a complement to the old Washington Market, was across the street from 1833-1873. However the shops on 6th between West 10th and 11th are still colloquially called the Jefferson Market.

This ad for Emil Talamini, a real estate agent at 450 6th Avenue complete with old-style phone number, has been here for decades but finally is beginning to succumb to years of sun beating on it. Interestingly, the ad reveals itself to be a palimpsest with an older painted ad underneath it that went up first, though the older ad is still unintelligible. According to Ephemeral New York, Talamini passed away in 1970. His name is still here, a full 50 years later. Note the old ALgonquin phone exchange.

I was attracted to this Federal townhouse at #56 West 10th. According to the Greenwich Village LPC report, “The exceptionally well preserved doorway is flanked by paired Ionic columns and narrow sidelights which retain their original delicate tracery, all surmounted by a transom surrounded by a fine egg and dart molding.” It was built in 1832. There is also some fine ironwork on the front stoop and railing, but getting good photos is hard to do because of the monster vehicles popular in 2020. The pineapples on it, some say, are symbols of hospitality.

A very similar Federal style townhouse at #52, constructed 1830-1831. At some time in the past it was made into a stable, hence the extra wide doorway on the left.

Next door is #50 West 10th. Note the wood “Grosvenor Boarding Stable” sign. The LPC says it was built as a stable between 1863 and 1879 which is a wider range than they usually pin it down to. In Ghost Signs: Clues to Downtown New York’s Past, Frank Mastropolo says it had become a residence by 1900. I find it amazing that the sign has made it through 140 years at least. The house has been home to playwright Edward Albee and Broadway lyricist Jerry Herman (whose website looks like 1995!)

Skipping a bit east, #18 West 10th is the former residence of poet Emma Lazarus (1849-1887). The building is an Italianate townhouse constructed in 1856; a family named the Lazaruses lived here in the 1880s. You know Emma Lazarus for the sonnet she wrote for the dedication of the Statue of Liberty in 1883, “The New Colossus.” It was inscribed on the statue’s pedestal in 1903:

Not like the brazen giant of Greek fame,

With conquering limbs astride from land to land;

Here at our sea-washed, sunset gates shall stand

A mighty woman with a torch, whose flame

Is the imprisoned lightning, and her name

Mother of Exiles. From her beacon-hand

Glows world-wide welcome; her mild eyes command

The air-bridged harbor that twin cities frame.

“Keep, ancient lands, your storied pomp!” cries she

With silent lips. “Give me your tired, your poor,

Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,

The wretched refuse of your teeming shore.

Send these, the homeless, tempest-tost to me,

I lift my lamp beside the golden door!”

#14 West 10th Street, the building on the left, is an Italianate townhouse constructed in 1856. Essayist/humorist/novelist Mark Twain (1835-1910) lived here in 1900-1901 and gave it up when the housekeeping proved too much for Mrs. Olivia Clemens, or so he wrote. Twain was a patron of the salon in the Hotel Griffou a block away on 9th Street, and also the C.O. Bigelow drugstore on 6th Avenue; the store still has logbooks inscribed with his prescriptions. The house gained infamy in 1987 when Joel Steinberg murdered his daughter Lisa at this address. Steinberg was convicted and was released after serving 17 years in prison.

I didn’t arrive at the Church of the Ascension, 5th Avenue and West 10th, at a propitious time, as morning February shadows covered half of it.

The first of two great churches along 5th Avenue in this area is the Episcopalian Church of the Ascension at 5th Avenue and West 10th Street, one of the first designs (1840-41) by renowned ecclesiastical architect Richard Upjohn. Ascension Church was founded in 1827 and spent its early years in a small church on Canal Street that burned down in 1839.

The Church’s early years on 5th Avenue were punctuated by the rare occurrence of a wedding of a sitting president: John Tyler and Julia Gardener were wed here in 1844. In 1888, a day nursery was founded at the Church, and in 1893 pew rentals were abolished, making church attendance free of charge. The Church was opened to all worshipers 24 hours a day between 1929 and 1966, when increasing crime forced the parish to close nights. During the Depression homeless men slept in the pews.

The adjoining parish house along 10th Street, also an Upjohn design, was altered in 1887 by McKim, Mead & White, and Stanford White redesigned the church interior from 1885-1889. The building is a NYC and National Historic Landmark. Interior artwork from Louis St. Gaudens and John Lafarge can be seen in the interior.

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop, and as always, “comment…as you see fit.”

4/19/20