Before the Great Infection, I spent a number of Saturdays (and some Sundays too) crisscrossing Manhattan via its numbered streets. Over the years, I’ve done this quite a few times and I was amazed at how much stuff I missed and how much material I knew about and posted here and there, but never really formalized or categorized. Eventually I might make these “crosstown” posts their own separate category. I’ve already posted much of 11th, 12th, 13th, and 14th (twice) and before I get tired of this, I might just do every one of NYC’s numbered crosstown streets, since I had so much fun finding things I never knew about and revisiting things that I did. Today, I’ll concentrate on 22nd Street, which I walked from west to east.

After I finish the streets I walked during this time, I’ll add a strip link to all those pages.

A word about the Great Infection. So far I’m more concerned about what it’s done to my investments (which are modest to begin with) but today, I was admonished to stay indoors after my Facebook photo posts of meandering around Woodside and Sunnyside were seen. Just to be on the safe side, I’ll have to confine myself close to home the next few weeks (months, maybe), whether or not I get ill. I hope everything’s back to normal—healthily and financially—before too much longer!

I began my walk in Hudson Yards. It’s hardly Forgotten, being brand new, and I’ve always been turned off by its collection of chrome and glass behemoths, which you can see in the background of this High Line shot (the USA’s highest public observation deck is clearly in the shot).

Surprisingly I discovered that if you walk to the west end of the High Line “campus” you can get on the High Line linear park without using a staircase or escalator. I’ll have to figure out the engineering behind this since I did not have to go up a staircase when entering the Yards at Hudson Boulevard and West 34th.

Contrary to many, I’ve been enthusiastic about the High Line over the years…

High Line Before the Hoopla, 1999

Back on the High Line Again, 2009

High Line from 20th-30th Streets

The High Line Section That Won’t Be a Park

A look east on West 23rd Street from the High Line overpass. In the distance we can see the Met Life Tower (1909) on the left, with the “supertall” One Madison and the Madison Square Park Tower, 45 East 22nd Street, on the right. In the forefront left is London Terrace, which takes up the entire block between 9th and 10th Avenues and West 23rd and 24th Streets.

The Half King, which was part authors,’ photographers,’ war correspondents’ and playwrights’ haunt and part neighborhood tavern on West 23rd at the High Line, was opened by author Sebastian Junger (“The Perfect Storm”) in 2000; high rents forced it to close in 2019. I was only in once, and I was all wet. I had spent a day riding around in the fireboat John J. Harvey with the Newtown Historical Society‘s Christina Wilkinson, and just before returning to port, the jets were turned on while we were standing on deck and we were completely drenched. We made our way to the Half King and dried out there.

Eduardo Kobra has become the NYC area’s premier building muralist, with “installations” depicting Michael Jackson (East Village), David Bowie (Jersey City) and much more, not only here but in many other countries. Here at 10th Avenue and West 22nd, he presents the “Mount Rushmore” of modern and pop art: Andy Warhol, Frieda Kahlo, Keith Haring, and Jean-Michel Basquiat. It’s fun to spot one I haven’t previously seen while I’m walking around.

The Empire was created by the Fodero Dining Car Company in the 1940s and renovated into a haute-cuisine restaurant in 1979. A stainless steel model of the Empire State Building was installed on the corner that vanished after the Empire closed in May 2010. Customers have included Babe Ruth, Albert Einstein, Barbra Streisand and Madonna. Miraculously, it’s survived intact despite the demise of similar diners in Chelsea and Hell’s Kitchen, such as the Cheyenne on 9th and West 33rd, the Market on 11th Avenue and West 43rd, the River Diner on 11th and West 37th, and the Munson on 11th and West 46th.

Nothing Could Be Finer: A Look at NYC Diners [FNY]

After numerous changes of ownership the Empire Diner reopened in 2014. Its menu still features more expensive fare than classic NYC diners.

Clement Clarke Moore Park, 10th Avenue and the south side of West 22nd. In the mid-18th Century, Captain Thomas Clarke acquired much of the acreage west of where 8th Avenue would be laid out from about West 20th to 28th Streets and named it after London’s Chelsea Royal hospital. Inheriting and adding to the property in 1813, Clarke’s great grandson, Clement Clarke Moore (the purported author of A Visit From St. Nicholas) developed lots in the neighborhood as streets were surveyed and laid out. He went so far as to dictate building styles and materials to the upper middle-class buyers of his lots. As with other sections of town flanking the Hudson, shipping and trade — in this case, lumber and breweries, inexorably swallowed the western edges, reaching Moore’s carefully conceived corner. [Sanna Feirstein, Naming New York]

Between 8th and 10th Avenues, houses on the south side of West 22nd are in the Chelsea Landmarked District; those on the north side are in the Chelsea North Landmarked District. Many buildings in this stretch were built in the 1830s and 1840s; #450 West 22nd, shown here, goes back to 1835.

This townhouse at #436 West 22nd was once occupied by actor Edwin Forrest, who unintentionally started one of the bloodiest riots in American history. In 1849, fighting broke out between anti-British supporters of American actor Edwin Forrest and wealthy patrons of English actor William Macready at the Astor Place Opera House. 20 people were killed when the Seventh Regiment National Guard fired on the rioters. A more complete account of the riot can be found in Luc Santé’s excellent book, “Low-Life.”

Unusually for NYC, some of Chelsea’s side street’s buildings go right up to 9th Avenue, with no corner building with a 9th Avenue address. That situation plays out here, with #400-412, built in 1856 for developer James N. Wells. Wells has been mentioned in FNY before as several of the small wood buildings he developed can still be seen on 9th Avenue between West 21st and 22nd Streets. Not many windows on the 9th Avenue side of #400!

318 West 22nd has had a lot going on. Currently it’s the bed and breakfast Colonial House Inn; in the 1970s it was home to the disco label West End Records and in the 1990s, first permanent home of the support organization Gay Men’s Health Crisis.

I was intrigued by 351-353 West 22nd, with its stone lion, arched entrance portals, and gate lampposts (which sometimes indicate that it’s a former mayoral residence). Built in 1874 by James Condie.

Here’s a map that will let you find all of NYC’s landmarked districts and individual landmarks.

The neo-gothic German Evangelical Lutheran Church of St. Paul, #315 West 22nd, is the third church building in this Lutheran congregation that originated in 1841 and whose first church building was located at 6th Avenue and West 15th Street. This church was designed by Francis Minuth and opened in 1888. Services are in German, except for a few years during WWII.

The German inscription over the entrance is in a quotation from John 14:6: “Jesus answered, ‘I am the way and the truth and the life. No one comes to the Father except through me.”

Across the street, 314 West 22nd is a peaceable kingdom.

The boutique Gem Hotel at the SW corner of 8th Avenue and West 22nd was for many years a welfare hotel/hovel called The Allerton. Poet/rocker Patti Smith and artist/photographer Robert Mapplethorpe stayed there in the 1970s, as recounted in Smith’s memoir.”Just Kids”:

These days marked the lowest point in our life together. I don’t remember how we found our way to the Allerton. It was a terrible place, dark and neglected, with dusty windows that overlooked the noisy street. . . . The springs of the ancient mattress poked through the stained sheet. The place reeked of piss and exterminator fluid, the wallpaper peeling like dead skin in summer. There was no running water in the corroded sink, only occasional rusted droplets plopping through the night . . . .

The place was filled with derelicts and junkies. I was no stranger to cheap hotels. . . . There was nothing romantic about this place, seeing half-naked guys trying to find a vein in limbs infested with sores. Everybody’s door was open because it was so hot, and I had to avert my eyes as I shuttled to and from the bathroom to rinse out cloths for Robert’s forehead. . . . His lumpy pillow was crawling with lice and they mingled with his damp matted curls.

The Allerton’s old plastic-lettered “Hotel” sign is still there, and the shell of its old neon sign is still there too.

The rowhouses on West 22nd between 7th and 8th Avenues are festooned with heads, both human and monstrous. What if the builders were representing Things from real life?

Surprisingly in rapidly gentrifying Chelsea, the SE corner building at West 22nd Street and 7th Avenue has been derelict since at least 2011, and has been joined in decrepitude by the adjoining two buildings since then.

The Irish Repertory Theatre was founded by by Ciarán O’Reilly and Charlotte Moore in 1988 and arrived at its present home at 132 West 22nd between 6th and 7th Avenues in 1995. A “repertory” is defined by Webster as “a company that presents several different plays, operas, or pieces usually alternately in the course of a season at one theater.” In March 2020 performances were cancelled or postponed because of the Virus.

The Irish Repertory Theatre provides a context for understanding the contemporary Irish-American experience through evocative works of theater, music, and dance. This mission is accomplished by staging the works of Irish and Irish-American classic and contemporary playwrights, encouraging the development of new works focused on the Irish and Irish-American experience, and producing the works of other cultures interpreted through the lens of an Irish sensibility. [Irish Repertory Theatre]

Ever since I worked in the area (on multiple occasions beginning in 1981) I have marveled at this sidewalk canopy on the Ehrich Brothers Building (see below). They’re more prevalent on buildings downtown in Tribeca.

The Ehrich Brothers Building (now home to Burlington Coat Factory), and its peculiarities, are an oft told tale in Forgotten NY and on my tours, but I enjoy telling it. In the late 1800s, 6th Avenue became a shopping mecca especially after the 6th Avenue El began to pull in people from all over the city in the 1870s. Firms congregated at what became shopping palaces that included the first outlets belonging to B. Altman (which survived until 1989) and R. H. Macy. The Big Kahuna of these stores was of course the Siegel-Cooper Building at 6th between West 18th and 19th, which had a window built into the top floor allowing customers to enter directly from the el platform!

The Ehrich Brothers opened a dry goods store at 8th and West 24th and operated a stagecoach between their shop and the 6th Avenue El. Finally they leased a location here at 6th and West 22nd-23rd and were finally solvent enough to build this large building at the same location in 1889. You can still see their “EB” digraph way up at the arched windows on the top floor. The brothers only made a 3% profit at the new location and closed in 1911 after 32 years here (counting the years they leased). The building they left behind is huge, and wraps around to West 22nd and 23rd, leaving only a holdout castiron front at 6th and 23rd (built by jeweler William Mohr in 1871; he wouldn’t sell his property to the Ehrichs).

To me the most fascinating elements on the building are the terra cotta cartouches and tiled pilasters bearing the letter K. They remind me of elements found in the early subway stations designed by Heins & LaFarge. But why are they there? Ehrich, obviously, doesn’t start with “K.” The reason is simple. After the Ehrichs closed up shop in 1911, the building was owned by Chicago merchants J.L. Kesner Company, who hired architects Taylor and Levi to add all the letter K’s. However, Kesner was deep in debt and closed in 1913 and thus, all those K’s were pertinent only for two years! They’ve been there ever since. The building deteriorated until the retail renaissance of the 1990s, when it was renovated.

Samuel Adams (not the brewer Sam Adams) opened a dry goods store as Hugh O’Neill and Ehrich Brothers had, on 6th Avenue between West 21st and 22nd Street in the 1880s, and it became so successful that silver miner Adams desired a larger place, and hired architects DeLemos & Cordes, who had previously built the palatial Siegel-Cooper Building two blocks south. Adams’ new building opened in 1900 (the date is cartouched on the top floor) and catered to a more upscale clientele than O’Neill and the Ehrichs. However the original Ladies’ Mile era passed quickly and the store closed in 1913. This building, too, became manufacturing (including Hershey’s candy bars) and lofts until it was renovated in the 1990s.

I spent a lot of time in the building between 1994 and 2008, when the ground floor hosted a Barnes & Noble “superstore” during the era when such outlets were popular. Today, Trader Joe’s occupies much of that space. You can still see “ADG” trigraphs at each of the building’s 3 massive arched entrances.

54 West 22nd is a Beaux Arts building constructed 1896-1897, and has delicate lead glass work on it street level picture windows. Note the metal cartouche on the left and right with the house number. They’re not in the shot but the original wrought iron fire escapes are still there too.

Surrounded by later Beaux Arts buildings, the Italianate #50-52 West 22nd are among the oldest building on the block. They were built in 1851 for developer John Latson. Higgins & Seiter, merchants of cut glass and china, established their business here in 1887 before moving to West 21st Street some years later. You can barely make out a Higgins & Seiter painted sign on the brickwork at the roof of the adjoining building, #54.

The “BXL Zoute” woodcut sign calls for a breakdown: “BXL” is the three-letter airport acronym for Brussels, while “zoute” refers to the Zoute in North Sea-side Belgian resort Knokke-Heist; thus, this is a Belgian eatery. I’m far from a gourmet and know nothing about Belgian fare except for waffles, so here’s the menu.

48 West 22nd serves as a Beaux Arts bookend with #54 for the two older buildings. It was constructed in 1904 and has an enormous front picture window on the second floor. It also has a plethora of painted ads: one, for Bonnell, Silver & Bowers, Retail and Wholesale Books on the east (left) side has just about faded into Eternity, but on the west side…

48 West 22nd juts out a bit into the sidewalk (or rather, #50 is set back); this provided a built-in billboard and advertising space for any businesses that wished to take advantage of that. A Miss Weber and her millinery shop was once such tenant at 48 West 22nd that did just that. A milliner is a fancy word for a business that sells women’s hats.

Miss Weber’s ad was one of the original Forgotten subjects when I first found it back in 1998 or 1999. I can tell you that this painted ad is in virtually the same shape it was in back then. Virtually no sun accesses this spot to fade it, and the paint was of sufficient quality to last for numerous decades. A person I turn to again and again for knowledge on the forgotten and faded ads of New York, Walter Grutchfield, has this to say about the Miss Weber’s Millinery ad:

Ida L. Weber (1879-1932) kept a millinery shop here at 48 W. 22 St. from 1911 to 1913. In 1913 she moved to 66 W. 39 St. in New York’s Millinery District and stayed there until going out of business around 1922/23.

That’s correct — this painted ad, which celebrated its centennial in 2011, remembers a business that was located on the street for just two years. Just like J.L. Kesner in the Ehrich Brothers building! Neither knew their promotions would be preserved for quite so long.

Above the Weber ad was another separate ad, but this one has sufficiently worn off as to no longer be decipherable.

West 22nd has its share of unusual eateries. Not a health food restaurant per se, Honeybrains at 34 West 22nd says “everything we create is 100% based on neuroscience and designed for your overall well-being.”

#3-7 West 22nd Street was built as a loft and manufacturing building in 1901. The entrances proclaim it as The Spinning Wheel Building although I cannot find any textiles manufacturing associated with it in my research. For some years, there was a plaque on the building proclaiming it as the final home of painter/telegraph inventor Samuel Morse (1791-1872). Morse died (and was buried in Green-Wood Cemetery) long before this building was constructed but he did live in a previous house on this location. I wonder what became of the plaque.

The Italianate Mortimer Building, officially 935-939 Broadway though it fronts on 5th Avenue and East 22nd, has been home to Restoration Hardware and has had that 2nd story clock as long as I remember. It was constructed as an office building and loft for Richard Mortimer in 1862. This building once housed the saloon of Dr. Jerry Thomas, master mixologist (for whom the Tom and Jerry was named). Cornelius Vanderbilt Jr., son of the Commodore, shot himself here on April 2, 1882, after a night of drinking and gambling.

I’ve only been in old-school sandwich shop Eisenberg’s, #174 5th Avenue off West 22nd, just once, in 2005 when I was working for the (now-defunct) Harris Publications up the block. As the sign says, the venerable hash slinger has been in business since 1929.

In the 1940 Municipal Archives photo there does indeed seem to be a sandwich shop at #174, though the perspective is unclear. The photographers were shooting blocks and lots, not individual signs.

I won’t dwell much on the iconic 1904 Flatiron Building except to say it isn’t photographed much at its north end on East 22nd. In any case, it’s covered with construction netting and sidewalk scaffolding and probably will be for some time.

A pair of unusual facades at #23 East 22 (actually the back end of One Madison on East 23rd) and some great (fire) escapes at #29 East 22nd.

There’s an interesting building on all 4 corners of Park Avenue South and East 22nd. At the northeast corner is the United Charities building, built in 1892 and expanded in 1909 to an R. H. Robertson design, to house several different charities under one roof: the Charity Organization Society, the Association for Improving the Condition of the Poor, the Children’s Aid Society, and the New York Mission and Tract Society. The NAACP was also founded in the building.

The Mills & Gibb Building on the northwest corner is a 15-story office building constructed in 1910 to house the retail and offices of the Mills & Gibb linen/textiles store. Note the cherub/plant carved hybrids.

In what’s becoming a familiar sight around town, at the SW corner Gramercy Place is a new residential or office tower constructed on the shell of a much older building. While The Bank for Savings was built in 1892, the high rise followed in 1987, almost a century later. The older section is home to a Morton Williams supermarket.

At the SE corner this steel-framed building with an extraordinary carven stone facade looks like it could be a church building and in fact that’s what it was built to be in 1894 as it was originally called the Church Missions Building, hosting offices of the Episcopal (Anglican) missions. Not shown here are friezes above the front entrance on Park Avenue South depicting St. Augustine of Hippo and Bishop Samuel Seabury (first American Anglican bishop) in mid-preach.

The Manhattan Trade School for Girls was established in 1905 and bounced around in the Union Square-Gramercy Park area before it was housed in this Collegiate Gothic building across the street from Baruch University on Lexington Avenue and East 22nd, designed by pre-eminent schools architect C.B.J. Snyder. It was one of four trade schools in its era that admitted young women. It is presently home to School of the Future serving 6th-12th grade students.

The Russell Sage Foundation building was built to host the charity begun by Margaret Sage in honor of her deceased husband, Wall Street financier Russell Sage, to a Florentine Renaissance design in red sandstone (officially Kingwood stone) by architect Grosvenor Atterbury in 1915. Carved panels emblematic of the ideals of the foundation can be found in second-floor escutcheons.

In 1909 Cord Meyer, the developer of Elmhurst, Queens, sold 100 acres south of the Long Island Rail Road to the Russell Sage Foundation, which commenced to piece together a nearly self-contained community, Forest Hills Gardens, from sixteen former truck farms throughout the 1910s and 1920s. Winding streets, Tudor brick buildings (many designed by Grosvenor Atterbury), and short, cast-iron streetlamps and street signs make the development completely unique in New York City. The Gardens, and the surrounding neighborhood, were called Forest Hills for nearby Forest Park.

The Sage imprint can also be found in Far Rockaway, where Mrs. Sage also funded the magnificent First Presbyterian Church, a.k.a. The Sage Memorial Church, with its stained glass windows designed by Louis Comfort Tiffany. It was built in 1909 by Cram, Goodhue and Ferguson.

This plaque, on an apartment house on the SE corner of Lexington and East 22nd, indicates where a home belonging to industrialist/philanthropist Peter Cooper (see below) used to stand.

This Ionic-columnated building at 137 East 22nd was built as the Children’s Court in 1916. It now hosts Baruch College’s Steven Newman Real Estate Institute. In fact this block is subnamed Children’s Court Way.

The site of Baruch College, on Lexington and East 23rd, has its beginnings in 1849 when the Free Academy, a boys’ secondary school, was opened here in a building designed by James Renwick, Jr. City College occupied the site by 1903 and its business school was established in 1919. The current campus buildings were constructed in 1928-1929, with absorptions such as the Children’s Court. The City College business school was named the Baruch School of Business in 1953 and in 1968, Baruch College, after CCNY graduate and presidential adviser Bernard Baruch, an 1889 graduate.

I had never before known of the existence of Gustavus Adolphus Swedish Lutheran Church a bit further east at #151 East 22nd. The church has occupied this spot since 1866, but constructed this church building in 1887, employing J. Cleveland Cady, the architect of two NYC classics—one demolished and one still standing: The old Metropolitan Opera House at Broadway and West 39th, which disappeared long ago, and a large wing of the American Museum of Natural History at Central Park and West 79th, thankfully still there. The distinctive church is made from gray Amherst Ohio stone.

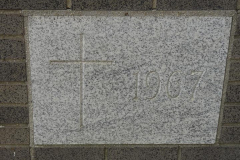

The cornerstone is distinctive. According to the Daytonian in Manhattan, when the cornerstone was laid a copy of NYC’s Swedish Language newspaper in 1887, as well as a copy of The New-York Times (still with a hyphen then), were placed within. But the exterior is unusual too. The date, 1887, is explainable enough, but the date shown on the left, 1865, is when the church was founded; and on the right, the numbers correspond to a Bible quote from the New Testament 1 Peter 2:6: “See, I lay a stone in Zion, a chosen and precious cornerstone, and the one who trusts in him will never be put to shame.”

The building is also home to The Little Synagogue, Cong. Tel Aviv, founded in 1986.

Though East 22nd Street was once home to a number of carriage houses serving business on bust 23rd Street (so did East 19th) this is the only one remaining at #150. It was built for a Miss E. L. Breese by architect Sidney Stratton in 1893.

I enjoy unusually narrow buildings. #158 East 22nd, just off 3rd Avenue, is only two windows across. I wonder what its story is.

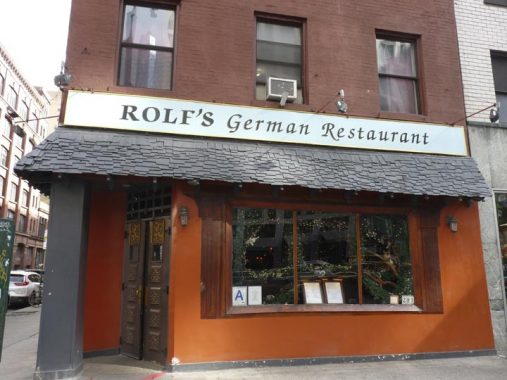

Rolf’s, on the southeast corner of East 22nd and 3rd Avenue, is less venerable than it appears, dating to the 1960s, but that’s almost a good 60 years now. It’s at its best during the holiday season. I’m a fan of meat and potatoes German fare.

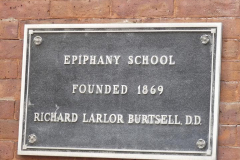

The south side of East 22nd between 2nd and 3rd Avenues is dominated by buildings associated with the venerable Catholic Church of the Epiphany (January 6th, the date, according to Church tradition, when pilgrims from the Middle East came bearing gifts for the newborn Christ). This is the oldest of the two, the parish grade school, constructed in 1888.

Though the parish is among the city’s oldest, its church building is among Manhattan’s newest Catholic churches, dedicated in 1967. In addition the church is built on Rose Hill, which before and during the Revolutionary War was the estate of General Horatio Gates, victor of the Battle of Saratoga. Polish patriot Thaddeus Kosciuszko, of Newtown Creek bridge fame, visited Gates here in 1797.

Now partially hidden by ever-present sidewalk scaffolding is the near terra cotta Deco trim on the first floor of the Gramercy Park Apartments, 2nd Avenue and East 22nd.

The east end of East 22nd is at 1st Avenue, where Peter Cooper Village comes into view.

Some people mistake Peter Cooper Village for Stuyvesant Town, since the two developments both feature high-rise brick apartment buildings, but the two projects are separate, divided each from the other by East 20th Street, which extends east to the Franklin D. Roosevelt Drive at the East River perimeter.

Both were built at the same time (late 1940s into the 1950s) by the Metropolitan Life Insurance company to house, at least at first, returning World War II veterans. The massive dual complex occupies 80 acres on what was once 18 square city blocks containing tenements and apartment buildings, as well as Manhattan’s former Gashouse District. In all, 600 buildings were razed and over 10,000 residents were forced to move out to make way for what remains Manhattan’s largest housing complex. It’s a city within a city and contains restaurants, banks, shops and medical facilities, as well as a “central park.” MetLife sold Stuyvesant Town and PCV to Tishman Speyer Properties in 2006, but they defaulted and the complex went into receivership.

In December 2015, the property was sold to Blackstone Group LP and Ivanhoé Cambridge, the real-estate arm of pension-fund giant Caisse de dépôt et placement du Québec for about $5.3 billion.

The complex was named for Peter Cooper (1791-1883) , the industrialist-inventor who conceived of the transatlantic cable, the steam railroad engine, and Jell-O. He established Cooper Union, the architecture, art, and engineering school still going strong in Cooper Square, Manhattan. He is buried in Green-Wood Cemetery.

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop, and as always, “comment…as you see fit.”

3/23/20

7 comments

Beautiful buildings and fascinating stories — thanks for sharing these!

Enjoyable post as usual Kevin. I definitely like the idea of covering a particular street end to end, I hope you’ll do more in the future.

One little nitpick though: the term “supertall” is used by architects to denote buildings over 984 feet or 300 meters in height, so although the taller of the two Hudson Yards towers at 1.296 feet is considered ”supertall”, the two Madison Square towers, both around 700 feet, are not. Source: am architecture student, hate seeing the term misused by clueless local politicians and neighborhood “activists.”

Also, speaking of Hudson Yards, you’ll be happy to hear that the project’s second phase is set to include a number of more traditional masonry-clad towers.

I hope that there are plans to reopen the Empire Diner in the near future under some new management especially since many free standing diners are becoming rare in Manhattan these days.

The old 13th Precinct building up until a couple of years ago survived on the north side of 22nd Street, just to the west of First Avenue. It was replaced in 1964 by the new, larger 13th Precinct on 21st Street, which for many years also housed the Police Academy. The old building was a throwback to the old Gas House District era along First Avenue, and probably managed to survive another half-century because 22nd between First and Second was pretty nondescript for years, but couldn’t hold out past the most recent real estate boom.

You could always spot a Tom Waits fan at the Empire Diner.

Great walk, thanks.

THANK YOU FOR TOURING W22St. I’ve lived in the stupidest building on the street since 12/89. It’s 235 where the steps go down into the newly renovated lobby and facade; it also has that ghastly garage below it. Opposite 235 are a row of lovely home that have had various celebs occupying them. At the NW corner of 22/7th is that disgusting nightmare building that should be raised. It was fun when a coffee bar occupied the lower floor for a few years, but the owner just leaves it corroding away. Diagonally across SE 22/7th Ave was supposed to be raised for an 8-10 story apt bldg but plans fell through supposedly, so there it stays rotting away. Ugh! My current owner just lowered my rent 20$ and I didn’t even ask her.

Never knew Epiphany was built on a location named Rose Hill. That means there’s been two Rose Hills in my educational life, Epiphany and Fordham College.