By SERGEY KADINSKY

Forgotten NY correspondent

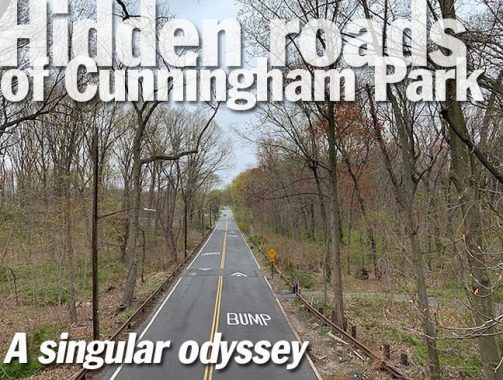

In the midst of the coronavirus crisis, nearly all aspects of the city’s public life have shut down to keep people away from each other. In the center of my borough’s eastern half is a sizable green space that offers ample distance from other people, and remnants of transportation history if one knows where to look.

I noticed one example of altered history when biking on the Queens segment of the Long Island Motor Parkway. Upon entering Cunningham Park, the historic route is blocked by the embankment carrying the Clearview Expressway, forcing the bike path to make a hard right and then into a long, dark tunnel under this highway.

Unlike the tunnels of comparable large parks such as Central Park or Prospect Park, the bike route tunnel under the Clearview Expressway is as charming as a dried-up storm sewer minus the smell. The western portal to this underpass opens into an expanse of sports fields where I’ve safely flown kites and picnicked with my children. Next to the fields is a forest where the original route of the Long Island Motor Parkway is hidden beneath the foliage.

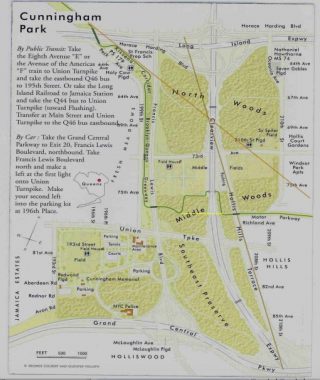

On the official map of Cunningham Park from 2009, I marked the park’s forgotten roads: in yellow the abandoned section of Motor Parkway; in brown the full route of Hollis Court Boulevard; and in orange the Stewart Railroad.

Deep in the western section of the park’s Middle Woods one can find the concrete posts of the Long Island Motor Parkway. They were installed here in 1926, marking the world’s first highway, a 45-mile route running from Fresh Meadows to Lake Ronkonkoma, a toll road used by wealthy individuals. It was extended west to Hillside Avenue in 1926, using a series of overpasses over selected roads.

The forested parcels of this park were acquired by the city as Hillside Park in 1928 in anticipation of the area’s urbanization. The forest was surrounded by farms but the city’s maps already had the prescribed street grid subdividinig the potato fields and golf courses. In 1935 the park was renamed for City Comptroller W. Arthur Cunningham, who died the previous year. In this 1951 city aerial survey, I highlighted the route of Motor Parkway when it was still running straight through the Middle Woods. The construction of Clearview Expressway in the following decade cut straight through the forest, interrupting the route of Motor Parkway and Hollis Court Boulevard.

This explains why there is a segment of this road north of the park and another to its south. A piece of Hollis Court Boulevard south of 73rd Avenue running through the park’s Middle Woods was renamed Hollis Hills Terrace. Driving on this road one can’t believe that this is inside the borders of the city. The road is very ancient, once known as Queens Road as it connected the old settlements of Flushing and Queens Village.

On the southern edge of Cunningham Park where the glacial terminal moraine descended down to the coastal plain, Hollis Court Boulevard passed under a graceful arch built in the 1930s to carry Grand Central Parkway atop this ridge. The arch’s design is nearly identical to Henry Hudson Parkway across Dyckman Street. That was the prewar Robert Moses. A generation later, he settled for functionality. Hollis Court Boulevard was broken up and Clearview Expressway was extended through this pass in the ridge. A stack interchange took the place of the Art Deco-style overpass.

Following the completion of Clearview Expressway and the bikeway’s underpass tunnel, Long Island Motor Parkway was rerouted through the forest, winding around the trees in stark contrast to the nearly straight direction that William K. Vanderbilt envisioned.

In tandem with the construction of Whitestone Bridge, the city extended Francis Lewis Boulevard across the length of the borough. In this promotional aerial photo from 1940 looking north, the oval road in the foreground is Epsom Course, a former racecourse in Holliswood that is today a residential street. Continuing north on the newly-built boulevard we see Grand Central Parkway, the toll-free Robert Moses creation that killed the privately-run Motor Parkway. The next road is Union Turnpike, at the time designated as State Route 25C and near it marked in yellow is Motor Parkway.

When Long Island Motor Parkway was built, Francis Lewis Boulevard did not yet exist, so the bridge carrying the parkway over the boulevard was built in 1940, after its conversion from a private highway to a public bikeway. Unlike the LIMP’s other bridges, which are concrete, this one is mostly metal in its design. The section of Francis Lewis Boulevard running through the park resembles a highway and for decades was used for illegal racing at night. In recent years speed cameras and a traffic light in the middle of this long stretch have reduced this dangerous pastime here.

The lineage of Francis Lewis Boulevard predates Cunningham Park and Whitestone Bridge. It was first proposed by the borough’s topographical bureau in 1912. In this 1922 Hagstrom map of Queens, we see an endless grid of paper streets blanketing the borough. Highlighted on a north-south route is Cross-Island Boulevard, proposed early on to run from Whitestone to Rosedale, uniting the future neighborhoods along the way. It was renamed in 1940 for local revolutionary Francis Lewis to avoid confusion with Cross Island Parkway. Motor Parkway defies the grid here with the mapmaker erroneously giving it underpasses instead of overpasses. A century later, west of the park the grid appears as planned. To its east is a set of garden apartment superblocks built in the 1950s. The other grid-defier here is the route of the Stewart Railroad followed by Peck and Underhill avenues. Stewart Avenue in Hollis Hills also follows this route.

[In 1922, most of the streets shown were “paper streets” existing in the imaginations of city planners and developers. –ed.]

From 1873 through 1879, dry goods magnate Alexander T. Stewart’s Central Railroad of Long Island (CRRLI) ran on a nearly straight line between Flushing and Floral Park. With a more heavily used line running through Jamaica and Stewart’s line running through sparsely populated farmland, the latter was abandoned. A 1928 photo by a surveyor from the Queens Borough President’s office shows the intact route within Cunningham Park, which was acquired that year by the city. On this note, Kevin Walsh documented a set of surveyor’s photos of the park from 1940 showing how this park appeared at that time.

In 1900, Louis Risse, the chief engineer of New York City’s Topographical Bureau and the designer of the Grand Concourse, proposed a linear park on the Stewart Line that later became the western Kissena Corridor. The western corridor and the right-of-way inside Cunningham Park were proposed for a grid-defying boulevard, which I highlighted. In the 1930s, Robert Moses designated Risse’s route as Kissena Corridor Park, connecting Flushing Meadows to Kissena Park to Cunningham Park. Today, there are no traces of the right-of-way. It is entirely overgrown with trees. A half century later, this corridor and the Motor Parkway bikeway were incorporated into the Brooklyn-Queens Greenway, a 40-mile series of bike routes running through parks from Coney Island to Fort Totten that is the city’s equivalent to the Appalachian Trail.

Having discussed the lost railroad, boulevards, expressway, and bikeway, there is one more transportation-related item that is unique to Cunningham Park. It is one of three parks in the city that has mountain bike trails. As it is with ski slopes, such trails have designations for experts, intermediates, and beginners.

One footbridge connects the two halves of the North Woods that are bisected by Clearview Expressway. The footbridge has the Gothic-style walkway lamps that were first documented by Kevin in 1999.

Clearview Expressway is among the later Robert Moses projects, lacking the decorative features of his prewar highways. It was rammed through Bayside despite fierce community opposition. Running a highway through the forest was easy, but then at Hillside Avenue the highway abruptly ended its run as a result of opposition from Hollis residents, who succeeded in saving their homes. The highway has its curiosities, as seen in Kevin’s page on its footbridge lamps and its now-gone railroad underpass.

Deep in the woods there are earthen ramps for mountain bikers to do stunts. The trailhead for this network of routes is at 210th Street and 67th Avenue. Despite its 358 acres, Cunningham Park is one of the least publicized of the vast parks of Queens. No stadiums, no pools, or rec centers here. It’s mostly fields and forests. Perfect for social distancing.

Sergey Kadinsky is the author of Hidden Waters of New York City: A History and Guide to 101 Forgotten Lakes, Ponds, Creeks, and Streams in the Five Boroughs (2016, Countryman Press) and the webmaster of Hidden Waters Blog.

4/20/20