January 2020 was still semi-normal in NYC, and at the time I was still camera-slinging around town. The winter of 2019-2020 was uncommonly mild, with just 3 or 4 days of accumulating snow, and morning lows dropped below twenty only twice. I was able to get out fairly frequently as a result, while taking care to marshal my limited funds to take care of Long Island Rail Road and subway fare, since I reside on the city’s edge a decent Eli Manning pass from Nassau County.

I decided to plunge into Calvary Cemetery from Sunnyside and then walk along the railroad tracks to southern Maspeth, then make my way north to the Woodside LIRR station. This area is mainly industrial, with several large cemeteries and a smattering of dwellings. It’s one of my favorite parts of town to putter around in though there are long stretches with not much to see, and I just tend to plunge through in heat and humidity. Of course in January I don’t have to concern myself with that…

GOOGLE MAP: SUNNYSIDE—CALVARY—MASPETH

Queens Boulevard still has a number of diners of a certain age even as Queens is losing its standalone diners one by one. The New Thompson’s Diner arrived at Queens Blvd. and 33rd Street in 1950 and the Master Company exterior metalwork is mostly unchanged, though the interior is largely altered, according to Michael Eagle and Mario Monti in Diners of New York.

A few blocks away between 39th and 40th is Pete’s Diner, which is not quite as venerable, a 1974 DeRaffele.

There’s hidden history in the diner’s name. Until the 19-teens, all of Queens Boulevard as far east as Broadway and Grand Avenue was called Thomson Avenue (without the “p”); east of that it was Hoffman Boulevard. Sections of both roads still exist, Thomson Avenue and Hoffman Drive.

Thomson Avenue, looking west from Van Dam Street. In Sunnyside, Van Dam Street, one of a plethora of Dutch “Van” names scattered all over town, stands in for 32nd Street and is an important truck route south to Greenpoint Avenue and the J.J. Byrne Bridge crossing the noisome and noxious Newtown Creek.

Evidence is scant, but if you look at a street map there is also a Van Dam Street in eastern Greenpoint running south 2 blocks, from Bridgewater Street to Meeker Avenue, and maybe the two were once slated to be connected, which explains why this never became 32nd Street? In any case, it won’t be happening now.

As shown on this 1909 map excerpt, Van Dam Street was once one of a number of named streets in Sunnyside, but only later was it extended south to meet Greenpoint Avenue.

At left we see LaGuardia Community College, part of the City University of NY, and established in 1967.

I call myself a diner aficionado but I have not been in the Van Dam Diner, at 47th Avenue. The exterior looks extensively remodeled but the interior appears classic. The diner serves LaGuardia students and faculty as well as workers in the heavily industrial surrounding area.

The diner may also serve cops, prison guards and other employees at the Queensboro Correctional Facility across the street. The two do seem to be color coordinated.

Also in the Van Dam mix is Indoor Extreme Sports, featuring axe throwing, paintball, archery tag and laser tag, and that 21st Century phenomenon, the “escape room” in which a team of players must solve a puzzle to gain escape.

The most famous thrown axe in history that was recorded on tape was on the Johnny Carson show…

Long Island City Center, 48-18 Van Dam, is in a remodeled building once home to the National Braid Manufacturing Corp. (as you can see here on Street View from 2015). it is now home to the Teamsters Local 813 and Local 27 IBT pension fund offices.

I thought Spandex went out with 1980s exercise videos, but it’s still widely used and Spandex World at Hunters Point Avenue and Van Dam Street is where you obtain it.

I headed southeast on Gale Avenue, one of the streets in a tiny grid that stands akilter the prevailing north-south grid. Along with Bradley and Starr Avenues as well as 31st Place and 34th-35th Streets the grid is what remains of an old town called Blissville. From here, you can see the increasing number of tall towers in Queens Plaza.

The neighborhood takes its name from Neziah Bliss, inventor, shipbuilder and industrialist, who owned most of the land here in the 1830s and 1840s. Bliss, a protégé of Robert Fulton, was an early steamboat pioneer and owned companies in Philadelphia and Cincinnati. Settling in Manhattan in 1827, his Novelty Iron Works supplied steamboat engines for area vessels. By 1832 he had acquired acreage on both sides of Newtown Creek, in Greenpoint and what would become the southern edge of Long Island City.

Bliss laid out streets in Greenpoint to facilitate his riverside shipbuilding concern and built a turnpike connecting it with Astoria (now Franklin Street in Greenpoint, Vernon Blvd. in Queens); he also instituted ferry service with Manhattan. Though most of Bliss’ activities were in Greenpoint, he is remembered chiefly by Blissville in Queens and by a stop on the Flushing Line subway (#7) that bears his family name: 46th Street was originally known as Bliss Street.

I had to return to Van Dam Street to cross under the Queens-Midtown Expressway. This is one of the busiest motorized crossroads in Queens, and pedestrians brave it at their peril. You have to wait for the perfect time when the light turns green and you can get the jump on turning cars and trucks.

On this workhorse building, an auto leasing center, a strip club ad shares space with a 9/11/01 tribute.

I’ve shown you the City View motel plenty of times—the Flemish Gothic building is a Forgotten NY favorite. Here’s a couple of photos from the back of the building on 35th Street off Bradley Avenue.

One of the most magnificent (former) public schools in Queens, the Flemish-design PS 80. Constructed around the beginning of the 20th Century, this was a school for only about 30 years. It later became a yeshiva, but stood vacant for a few decades until an investor unsuccessfully attempted to operate a hotel, In the 1980s, new owner Mohammed Daoud partnered with the Best Western motel chain, making it possibly the best-looking Best Western in North America. Of late, the City View is still going strong, but the Best Western connection has seemingly been severed.

A decade-long fascination with the place prompted me, in 2005, to call the front desk and ask for one of the rooms with… a city view, which earned me an annoyed rebuke. Well, if you’re calling it the City View…

A look west on 35th, Blissville’s mostly residential street, allows a glimpse across Newtown Creek to the NYC’s Department of Sanitation’s “digester eggs” known by locals as the Shit Tits.

Through a process called anaerobic digestion they reduce the volume of sludge (what’s left of sewage after debris and liquid are removed) by nearly half. The egg shape is a space- efficient and minimal maintenance European design.

In the 1960s the oil refineries moved out of Greenpoint and the sewage treatment facility moved in… To this day it is a source of various pungent odors which, to your relief, current Internet technology prevents me from presenting here. The fact, however, is that the facility has cut down on the amount of raw sewage flowing into the East River and has brought some amount of government attention to the environmental situation in Greenpoint. So it is a lesser evil than the refineries. Alex Reisner

The front gate of Calvary Cemetery on Gale and Greenpoint Avenues comes into view. The gate is emblazoned with the name St. Calixtus. Calixtus, or Callistus I, was an early pope (217-222) and was martyred (allegedly by being thrown down a well) by the Roman Empire for his beliefs. His predecessor, Pope Zephyrinus, entrusted to him the care of the burial vaults along the Appian Way where many popes during the 3rd century were interred, as rediscovered in an archeological expedition in 1849. He is the patron saint of cemetery workers.

Calvary’s landmarked office building and the Catholic Church of St. Raphael come into view once I enter the grounds.

St. Raphael’s Church, named for an archangel, dominates views from Hunters Point, Blissville, Calvary Cemetery, and Sunnyside. It was built in 1885 here at Greenpoint and Hunters Point Avenues and replaced an earlier structure; the parish dates to 1865. The reputed architect is Patrick Keely, the famed architect of mostly Catholic churches in the 19th Century.

As always, the most comprehensive history of this church, as well as others, is found on the American Guild of Organists’ NYC pages.

Holy Calvary

In the mid-19th Century Manhattan was getting so crowded (by 1845 the island was fully built up south of about 42nd Street) that it was running out of cemetery space. The two largest cemeteries had been developed by Trinity Cemetery, in the churchyard adjacent to its ancient Broadway and Wall Street location, and uptown in the furthest reaches of civilized Manhattan territory, the wild north of 155th and Broadway.

By the 1840s Brooklyn’s largest cemeteries, Green-Wood and Most Holy Trinity, and Woodlawn in the Bronx were accepting interments; and in Staten Island there was Moravian, developed in the 1760s, and myriads of smaller cemeteries.

Queens, too, had dozens of tiny burial grounds scattered around, many dating to the mid-1600s. In 1847 the Rural Cemetery Act was passed, prohibiting any new burial grounds from being established on the island of Manhattan. Presciently anticipating the legislation, trustees of the old St. Patrick’s Cathedral on Mulberry Street in what is today known as Little Italy began buying up property in western Queens. Calvary Cemetery, named for the hill where Christ was crucified, opened in 1848. The original acreage had been nearly filled by the late 1860s, so additional surrounding acreage was later purchased to the east.

I once spent a good half hour looking for Esther Ennis in Calvary, but today I found her right away; I must be getting used to the place. She was the first interment at Calvary Cemetery in 1848. Not much is known of Esther Ennis, though according to legend she died ‘of a broken heart’ at age 29. This stone was placed over 100 years after her death, judging from the styling. This is not the earliest grave in Calvary, though, as we will see.

I feel no discomfort in cemeteries; I feel at peace, which no doubt is the intention of its landscapers and maintenance crew as well as its long-ago planners and developers. Graveyards are rarely the places of terror and murder as depicted in the horror stories. There is no one else around when I tend to visit. However, a few years ago I encountered a bagpiper. Or was it an accordionist or a saxophonist? My memory is fuzzy now. Having been raised Catholic Irish, I feel especially at home at Holy Calvary because it is filled with Irish Catholics as well, I’d have to make it as much as 75% in the original section here. Other sections are rather more ecumenical.

The third-tallest building in the Cemetery, after the gatehouse and chapel, is the Johnston Mausoleum, which is prominently viewable from buses entering the Queens Midtown Expressway.

The real show stopper at Calvary Cemetery is the Johnston Memorial. Erected in 1873, at a cost of $200,000 (that would translate to about $4 million in modern terms) the Johnston Memorial, like the Almirall Chapel, forms a centerpiece of the section it’s found in. There were three Johnston brothers, who operated a very successful milliners business on Manhattan’s “Lady’s mile,” specifically on Fifth Avenue and 22nd street. Brother Charles died in 1864, and brother John left the world in 1887. The remaining Johnston brother, Robert, went mad with grief and fell into poverty. He died in a barn on the grounds of a an upstate nunnery, during a thunderstorm, in 1888. [Newtown Pentacle]

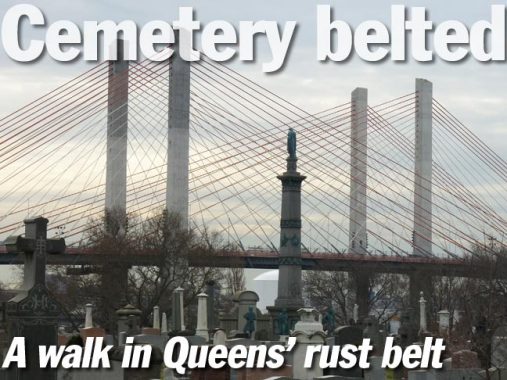

The New Kosciuszko Bridge, which opened in sections in 2017 and 2019, is visible prominently from Calvary, as was its immediate predecessor, the Old K, and its predecessor, Penny Bridge, which spanned the creek at Meeker Avenue and at one time did cost a penny to cross.

Calvary Park is one of the few parks located within a NYC cemetery (though Drake Park in Hunts Point is coterminous with a family cemetery).

Calvary Cemetery’s Civil War memorial is owned and operated by the NYC Parks Department, explaining the maple leaf Parks sign. It’s the only NYC park completely surrounded by a cemetery. While Green-Wood Cemetery Soldiers’ Monument has been newly spiffed and polished, Calvary’s copper is resolutely verdigris’ed.

On April 28, 1863, the City of New York purchased the land for this park from the Trustees of St. Patrick’s Cathedral and granted Parks jurisdiction over it. The land transaction charter stated that Parks would use the land as a burial ground for soldiers who fought for the Union during the Civil War (1861-65) and died in New York hospitals. Parks is responsible for the maintenance of the Civil War monument, the statuary, and the surrounding vegetation. Twenty-one Roman Catholic Civil War Union soldiers are buried here. The last burial took place in 1909…

…The monument features bronze sculptures by Daniel Draddy, fabricated by Maurice J. Power, and was dedicated in 1866. Mayor John T. Hoffman (1866-68) and the Board of Aldermen donated it to the City of New York. The 50-foot granite obelisk, which stands on a 40 x 40 foot plot, originally had a cannon at each corner, and a bronze eagle once perched on a granite pedestal at each corner of the plot. The column is surmounted by a bronze figure representing peace. Four life-size figures of Civil War soldiers stand on the pedestals. In 1929, for $13,950, the monument was given a new fence, and its bronze and granite details replaced or restored. The granite column is decorated with bronze garlands and ornamental flags. NYC Parks

Like Mount Zion Cemetery (see below) Calvary Cemetery incorporates an even older family cemetery. The Alsop family burial site, in a southern corner of Calvary Cemetery in view of the Kosciusko Bridge, pre-existed Calvary by over a century and was simply incorporated into Calvary when the land it stood on was purchased by St. Patrick’s Cathedral. Other unusual cemetery placements are the Drake Park cemetery in Hunts Point, Bronx, and in something of a reversal, the colonial-era Quaker Cemetery in Prospect Park is where famed actor Montgomery Clift was laid to rest.

Richard Alsop had been bequeathed the land by his cousin, British immigrant Thomas Wandell.

I have a full page on Calvary Cemetery here, and Mitch Waxman, the uncrowned King of Calvary, has written about it extensively in the Newtown Pentacle.

When I’m in the vicinity I like to head down 43rd Street to the railroad tracks. This is actually a busy route because 43rd Street goes to the parking lot of Restaurant Depot, a membership-based food and supplies store reserved for the hospitality industry: however, it has been opened to the general public during the coronavirus crisis.

In NYC, I’m fascinated by access to grade-level railroad tracks and their interaction with roads. In fact I have written an entire multipart series of these roadway-railroad encounters. These tracks, which offer a view of the New K Bridge, also offered a view of the old bridge, and the first bridge: they’ve been here since the mid-1800s. I can stand comfortably on the tracks because actual freight trains use them only a few times a day and lack a third rail: only self-powered trainsets can use them. I’d advise against walking the tracks, though, the freights can be upon you fairly quickly.

The tracks also hosted passenger trains (only a few daily at the end) until 1998. Tragedy occurred on these tracks in 1893 when a collision cost fifteen people their lives, including Oscar and Maggie Dietzel. Their Green-Wood cemetery memorial contains a marble sculpture of crashing passenger trains; it’s been considerably weather-worn over the years.

I moved ahead on 56th Road, past junkyards, light manufacturing and warehousing along the Long Island Rail Road tracks shown earlier until I reached 56th Terrace (this is one of the areas in Queens where all the streets have the same number).

56th Terrace is one of the oldest roads in the area. Though today it connects 56th Road and 58th Street, it used to be called “The Road to Town Landing” and dead-ended at an arm of Maspeth Creek, a Newtown Creek tributary that once trickled as far north as today’s Queens Midtown Expressway; long ago, it was shoehorned and dredged into a short, deep canal terminating at 49th Street as a 2020 map shows.

Why was The Road to Town Landing important? It was the site of the home of a prominent canal builder, De Witt Clinton, who held nearly every available elected office in New York City and State (but could not get elected president). In December 2019, the Newtown Historical Society installed a sign at 56th Terrace and 58th Street a stone’s throw from the former mansion’s location.

The junction of 56th Road, 58th Street and Maurice Avenue has featured a few historic structures—or rather, did, as I’ll talk about presently. This 3-story house, at 57th Place and 57th Road, over a century ago was home to the Maurice family.

James Maurice was a U.S. Congressman, Maspeth landholder and founder of the now disassembled St. Saviour’s Church, and was a co-founder of nearby Mount Olivet Cemetery. He is buried in that cemetery along with his two brothers and three sisters, none of whom ever married. Compared to larger cemeteries around town like Green-Wood, Woodlawn and Evergreens, Mt. Olivet is a bit short on star power; however, Prince Matchabelli and Helena Rubenstein of cosmetics fame are buried here, as is gangster Jack “Legs” Diamond, who according to legend, was a good dancer, hence the nickname.

St. Saviour’s Episcopal Church and its parsonage were located at 57th Drive and 58th Street in Maspeth. St. Saviour’s, designed by prominent architect Richard Upjohn, had been there since 1847, before the present street grid had been laid out, on land donated by James Maurice, the prominent lawyer, politician, and landowner. It was torched by vandals in 1970 and considerably altered, after which a Korean congregation moved in. In 2007 the church was disassembled and moved into storage after a developer purchased the property, building warehouses on it; the church awaits reassembly…somewhere.

The Clinton Diner (named for the nearby DeWitt Clinton mansion), long a place of rest and sustenance (at least for me) in these parts, at Maspeth Avenue and 57th Place, was renamed the Goodfellas Diner because it, along with Jackson Heights’ Airline Diner, featured prominently in scenes from the 1990 Martin Scorcese mob classic. Unfortunately the diner suffered a devastating fire in 2018, and shows no sign of reopening in 2020. We can dream. Apparently it’s a Kullman from the 1930s that was renovated in the 1960s.

I once repaired to the Clinton Diner after cracking my head open on the Metropolitan Avenue Bridge, tripping on a curb and hitting the rail. While I was scarfing down lunch, the jaw movements reopened the wound. Mitch (who was with me) called for an ambulance and I was hustled off to Elmhurst Hospital for stitches. All in a day’s work for Forgotten New York.

Another building named for Clinton in the area is at the corner of 56th Terrace and 58th Street, the erstwhile Clinton Hall. According to historian Paul Graziano in the Spring 2020 Juniper Berry, the publication of the Juniper Park Civic Association, the site of the mansion became a German beer garden founded by Peter Grussy in 1870 called Grussy’s Clinton Park. Clinton Hall appeared in the early 20th Century and was once billed as Long Island’s biggest dance hall, featuring bowling alleys, basketball courts and a pool room. It appears to be used for warehousing these days.

I can’t be sure what the original lettering was on this billboard sign for kosher foods at 56th Avenue and Maurice; a faded sign saying “Schreiber” appears on the exterior. Until 1986, this was a Hebrew National distributor.

Mount Zion Cemetery

Mount Zion, a Jewish cemetery, occupies about 80 acres in Maspeth near New Calvary Cemetery and the BQE, bounded roughly by Maurice Avenue, 54th Avenue, 58th Street, 52nd road, 59th Place and Tyler Avenue. It was opened in the early 1890s under the auspices of Chevra Bani Sholom and later by the Elmwier Cemetery Association (Elmwier Avenue is a former name of 54th Avenue).

A walk in Mount Zion will produce a surprising and poignant reminder of burial practices long forgotten… the faces of the dead are preserved on some of the tombstones. In a process known as ‘enameling,’ photographs of the deceased are burned into porcelain (in a process described in detail in John Yang’s book, “Mount Zion: Sepulchral Photographs.”) This was a custom brought to the USA by Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe. A look at newer gravesites in NYC will reveal that placing photos of the deceased on gravestones is returning.

Like Calvary Cemetery, Mount Zion incorporates an older family cemetery founded by the Betts family.

Mt. Zion Cemetery is also where many of the victims of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire of 1911 are buried. On Saturday, March 25 of that year, as quitting time approached, a fire broke out on the eighth floor of the Asch Building near Washington Square, and spread rapidly on the top three floors of the building. In a scene reminiscent of the General Slocum tragedy 7 years before, fire hoses were woefully inadequate to battle the flames, the lone fire escape was rickety and rusted, and the doors to the exits were locked to insure that the mostly immigrant women working the sewing tables would not wander or steal anything.

There was little escape from the flames and in a scenario that foreshadowed the 9/11/01 terrorist attack, the women were forced to make the choice to jump out of windows or burn to death, and many chose the former. While some were able to escape by an open staircase and an elevator, 145 employees would perish. In less than a half hour, the fire was brought under control. Triangle owners Isaac Harris and Max Blanck were charged with manslaughter; after a two-week trial they were found innocent.

Three years after the fire, on March 11, 1914, twenty-three civil suits against the owner of the Asch Building were settled. The average recovery was $75 per life lost.

Big Bush Park, on 61st Street between Laurel Hill and Queens Boulevards, isn’t named for what you might think it’s named for. Until about 35 years ago the stretch of 61st Street that is accompanied by a ramp connecting Queens Boulevard with the BQE was called Bush Street.

The most prominent sight along Queens Boulevard in Woodside is the presence of the Big Six Towers, located between 59th and 63rd Streets, Queens Boulevard and 47th Avenue. They were developed, like Electchester in Flushing, by a trade union. The New York Typographical Union (Local 6) largely funded the project, completed in 1963, and at one point, one-third of its tenants are active or retired union members. The AFL-CIO invested heavily in the towers in 2008 to help keep its apartments affordable for middle-class families.

Firefighters are known as New York’s Bravest (as cops are Finest, and sanitation is Strongest; they’ll have to come up with something for healthcare workers after the virus is controlled). Rescue 4/Engine 292 is located on the south side of Queens Boulevard between 64th and 65th Streets.

A look at the sign reveals a baffling convention at the Department of Transportation sign shop. The top line has to have the larger type, no matter what, even if the emphasis should be on the last word or words. Hence, “Boulevard” has to be large, and “of Bravery” has to be small. Some managers apparently buck the convention and design the sign properly, but too many go out the door like this.

Oof.

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop, and as always, “comment…as you see fit.”

4/5/20