In March 2019 I was given the opportunity to appear in the New York Post for Forgotten New York’s 20th anniversary, with an interview by the Post‘s Hana Alberts and a photo taken by the paper’s Brian Zak. I suggested to Brian that we meet in Mount Zion Cemetery in western Maspeth in Queens’ Cemetery Belt because there are plenty of picturesque vistas. Zak would up taking over 200 photos of which the Post used one. Though I’m relatively satisfied with the face in my bathroom mirror every morning, I photograph like a bridge troll, but fortunately the Post didn’t use a closeup.

It was a brilliant day in late March and I decided to walk from the Woodside on the LIRR to the Cemetery, then into Maspeth, have a slice or two of sesame seed pizza at Joey’s and then head for home. Today I think I was able to snag some interesting infrastructural bits and pieces.

The Long Island Rail Road (with the LIRR it’s always two words) complex as presently configured took shape in 1916 with the elimination of grade crossings on the main branch of the railroad, which is bridged over Roosevelt Avenue, seen in the background with the #7 elevated IRT subway and its 61st Street station. The subway and railroad are not integrated and take separate fares, though some sort of single fare for patrons of both lines may be worked out with the OMNY fare access system now being instituted and scheduled to be completed in 2023.

The two tracks seen at right belong to the Port Washington Branch. Besides Penn Station itself, this is the only place where Port Washington Branch riders may transfer to other LIRR branches, but the MTA makes no real effort to match up schedules. Two separate fares are of course required for Port Washington rides and other branch rides.

The MTA has forgotten about this sign at the 62nd Street entrance to the eastbound platform, the only sign left that refers to Shea Stadium. The Mets’ old home closed at season’s end in 2008 and was torn down by 2009.

The most prominent sight walking south in Woodside is the presence of the Big Six Towers, located between 59th and 63rd Streets, Queens Boulevard and 47th Avenue. They were developed, like Electchester in Flushing, by a trade union. The New York Typographical Union (Local 6) largely funded the project, completed in 1963, and at one point, one-third of its tenants are active or retired union members. The AFL-CIO invested heavily in the towers in 2008 to help keep its apartments affordable for middle-class families.

One element in Woodside that I never expected to see there was the presence of a step street. On the battered Hagstrom that I use 48th Avenue between 58th Lane and 59th Street is shown like any other street — but on a great resource I use now, Open Street Map, it has the dotted red line that indicates a step street. Decades ago when these streets were built, the incline was considered too great to carry vehicles.

The only other step street I am aware of in Queens carries 53rd Avenue down a steep incline between 64th and 65th Place in Maspeth. Queens certainly has opportunities for other ones especially in its hilly middle section in Jamaica Estates and Richmond Hill, but I haven’t found others.

Rising real estate costs and an ever-expanding urban frontier led NYC to pass a law prohibiting any more burials in Manhattan in 1852. Churches and synagogues, which had begun to make a profit running cemeteries, looked east to Queens County, then a vast forest containing farms and the occasional small town like Flushing and Jamaica. St. Patrick’s Cathedral opened Calvary Cemetery in 1848, a couple of years before its big 5th Avenue cathedral opened.

Mount Zion, a Jewish cemetery, occupies about 80 acres in Maspeth near New Calvary Cemetery and the BQE. It was opened in the early 1890s under the auspices of Chevra Bani Sholom and later by the Elmwier Cemetery Association (Elmwier Avenue is a former name of 54th Avenue, where the present-day main cemetery entrance is today; there is also an entrance on the cemetery’s north side on Tyler Avenue).

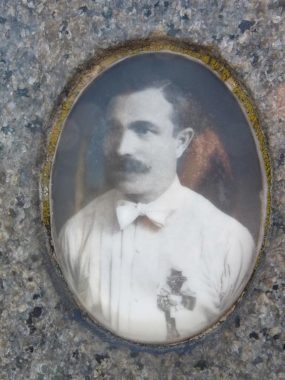

A walk in Mount Zion will produce a surprising and poignant reminder of burial practices long forgotten… the faces of the dead are preserved on some of the tombstones.

In a process known as ‘enameling,’ photographs of the deceased are burned into porcelain (in a process described in detail in John Yang’s book, “Mount Zion: Sepulchral Photographs.”) This was a custom brought to the USA by Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe. A look at newer gravesites in NYC will reveal that placing photos of the deceased on gravestones is returning. In the Mt. Zion stones, the tablets are mostly oval and some are gilt-edged. Some are heavily retouched, so they look vaguely unreal, as if they were drawn, not shot with a camera. Some are formally posed while some are candid. Many of them capture people in their prime. Most of the men are attired in suits, while the women sport the big hats so popular in the 1920s and 30s.

Mt. Zion Cemetery is also where many of the victims of the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire of 1911 are buried. On Saturday, March 25 of that year, as quitting time approached, a fire broke out on the eighth floor of the Asch Building near Washington Square, and spread rapidly on the top three floors of the building.

Fire hoses were woefully inadequate to battle the flames, the lone fire escape was rickety and rusted, and the doors to the exits were locked to insure that the mostly immigrant women working the sewing tables would not wander or steal anything. There was little escape from the flames and in a scenario that foreshadowed the 9/11 terrorist attack, the women were forced to jump out of windows or burn to death, and many chose the former.

While some were able to escape by an open staircase and an elevator, 145 employees would perish. In less than a half hour, the fire was brought under control. Triangle owners Isaac Harris and Max Blanck were charged with manslaughter; after a two-week trial they were found innocent. Three years after the fire, on March 11, 1914, twenty-three civil suits against the owner of the Asch Building were settled. The average recovery was $75 per life lost.

Some very old gravestones, going back to the 18th Century, can be found in the southwest corner of Mt. Zion Cemetery at 54th Avenue and 58th Street. This is the Betts family burial grounds; the Betts were the descendants of Captain Richard Betts, an early settler who built a home on the Road to Newtown (now Borden Avenue) in 1656. Betts, a native of Herefordshire, England, arrived in Maspeth by way of Ipswich, Massachusetts, in 1648. The Betts family was prominent in Maspeth and Woodside for over 250 years.

According to legend, Richard Betts dug his own grave at age 100 in anticipation of his impending death. That’s the most Irish thing I’ve ever heard,” exclaimed filmmaker Heather Quinlan (If These Knishes Could Talk) when I told her the story. Betts was English, though.

Via Street View, here’s an overhead view of Betts Cemetery within Mt. Zion.

Mt. Zion is open 6 days a week, and while Yang’s book is hard to find on area bookshelves, it is available for purchase at Mt. Zion’s office, which is modern and has a friendly staff. Enameled portraits from the same era can also be seen at nearby Mt. Olivet Cemetery.

Looking west on 54th Avenue towers in western Queens and Manhattan seem to mix together, though the East River separates them.

In 1928, much of Queens was still largely unpopulated and unbuilt-upon. Ridgewood, however, was an exception to the rule, due to its proximity to Brooklyn, and real estate developers hoped to capitalize on the cachet of the neighborhood. By then, Ridgewood was dominated by attached brick and brownstone houses, as well as blocks of handsome, yellow-bricked apartments constructed by developer Gustave X. Mathews. He built from materials created in the Staten Island kilns of Balthazar Kreischer.

In that year, the developers Realty Associates purchased 70 acres in a neighborhood then labeled as “North Ridgewood” but now a part of northern Maspeth roughly defined by Maurice Avenue, 64th Street, Grand Avenue and 74th Street. Builder John Aylmer set to work constructing two and six-family homes in the newly-named Ridgewood Plateau, so named for its location atop one of Queens’ higher hills.

To identify the development, Realty Associates placed brick posts emblazoned with the words “Ridgewood Plateau” carved into the concrete, as well as a quartet of iron arches at 65th Place, Maurice Avenue and Jay Avenue, marking the northern and southern ends of the development. The words “Ridgewood Plateau” were painted in gold leaf on a plaque attached to the iron arches’ apices.

Over time, the iron arches became rusted and the gold leaf was worn off. Occasionally, an iron arch would be painted, staving off further rust, but no real ongoing maintenance would be performed until just recently when the Juniper Park Civic Association, the Newtown Historical Society, Maspeth Federal Savings, the Communities of Maspeth and Elmhurst Together and Maspeth’s O’Neill’s Restaurant arranged for the restoration of the arches by Woodside artisan Larry Madine. The first fruits of the restoration work were revealed a few years ago at Jay Avenue.

As part of the 1928 development, 65th Place was paved and graded from Roosevelt to Grand Avenues. Along with 69th Street, once called Fisk Avenue, 65th Place provides a direct vehicular route from Woodside to what was once Ridgewood Plateau.

The brickwork on the arches at Jay Avenue preserve 65th Place’s former name, Hyatt Avenue.

A Swiveling Corvington, Grand Avenue in Maspeth. (Not a bad band name.) A stiff wind will often spin around the top halves of Corvington lamps (and even some bishop crooks) around town, as the top half of the shaft is insufficiently fastened to the bottom half.

Garlinge Triangle, where 57th Avenue diverges from Grand at 72nd Place, named for a local soldier Private Walter Garlinge, killed in World War 1. 57th Avenue is the former Hempstead Plank Road, which reached eastern Queens by crossing the old Strong’s Causeway (now replaced by the Long Island expressway) across the Flushing River. Many original old roads in Queens have their identities hidden by the modern street numbering system.

Maspeth was never a town (instead, it was part of Newtown, which encompassed much of western Queens, until the towns system was abolished when Queens consolidated with Greater New York in 1898). Maspeth Town Hall on 72nd Street did serve in a municipal capacity before becoming a police stationhouse and later, a public school. It went up in 1897, not 1802, as its sign says. Currently it functions as a community center.

Maspeth is located atop a rather high hill, Ridgewood Plateau (see above). Here’s a view of 72nd Street looking north with Woodside in clear view.

Someday, I’d like to take a walk with someone from Verizon and they can tell me what, exactly, all the wires are for and where they go.

Crosson Green is a tiny park arranged along 68th Street at the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway, just south of Woodside Avenue. When the BQE was angled through the region in 1955, a series of small open spaces were created that were turned into “vest pocket” parks. This one was named for Father Matthew J. Crosson (1908-1986) who spent part of his youth in Woodside and served in the South Pacific in WWII as a Army chaplain, winning citations for bravery.

Other such small parks along the BQE were interestingly named for aides of traffic czar Robert Moses: Jennings Park, Latham Park, Sherry Park, and Spargo Park.

The Winfield Dutch Reformed Church was built in 1880 by members of the Reformed Church of Newtown. The building was originally closer to Queens Boulevard, but was moved intact to its present location on 67th Street off of Woodside Avenue in 1907. Since the 1960’s, the church’s congregation has been made up mainly of Taiwanese immigrants.

Winfield was a small subset in eastern Woodside that has been mostly absorbed by its parent neighborhood. Speculation exists that it was named for General Winfield Scott, who served in the War of 1812, Mexican, and Civil Wars.

I’d like to solve the puzzle, Pat!

Of late the pages have been a bit shorter, and less have been posted, but the reason for it is a positive one, as I have been working at a freelance job that takes up much of my time — the other part scouting and writing FNY tours, but as soon as things quiet down a bit, FNY posts will become a bit more frequent. I do like a shorter feature page format, though!

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop, and as always, “comment…as you see fit.”

6/24/19

11 comments

I often wonder what the deal was with all those wires hanging on wooden posts. I hope you can find out for us what is the need for them all.

Great article! Thanks for the interesting history lesson.

The Woodside LIRR station project a century-plus ago was more than a grade crossing elimination. It was also a partial relocation of the right of way to eliminate some reverse curves and thus straighten the tracks. The grade crossing elimination included a massive six-track bridge over Queens Boulevard that to this day carries both the four Main Line and two Port Washington Branch tracks. About ¾ mile east the Port Washington tracks have their own smaller bridge over Queens Boulevard. Both replaced at-grade crossings, which even in 1916 were extremely dangerous and fraught with train-motor vehicle conflicts. The arrival of the IRT subway in 1917 was no doubt an impetus to rebuild the LIRR and provide an appropriate transfer station between the two systems.

In between the two LIRR bridges, where the Port Washington and Main Line tracks come together, there was, until 1974, an interlocking (a set of switches, signals, and a control tower adjacent) that allowed trains to move between the Main Line and Port Washington Branch. A fire that year destroyed the tower and the associated interlocking, which were called WIN (for Winfield), no doubt for the subset neighborhood described in this posting.

In Winfield, between the two LIRR Queens Boulevard bridges, is the more impressive New York Connecting Railroad bridge, a large three track that was discussed in an earlier FNY article. It only handles freight trains and doesn’t see the traffic that its LIRR brethren carry.

Congrats on the job!! All posts are welcome. Paraphrasing, “post…as you see fit.”

The same way that Mount Zion Cemetery envelops the tiny Betts Cemetery, nearby Calvary covers the tiny Alsop family cemetery and Mount Hebron Cemetery envelops the Willett family plot.

Is “Crosson Green” a pun? As in “Don’t Crosson Red”?

According to the Mt. Zion Cemetery web site, the gates are open Sunday through Friday 8:30 AM to 4:00 PM, closed on Saturdays and some Jewish holidays..

Your picture of the LIRR Woodside station reminded me of something I had been told when young.

At the east end of the west bound station, there was a holding area, or bin, for coal. It still had the black coal dust stains

And was lined by what looked like Belgian block.

It was removed when the station was re-constructed some dozen tears ago when those gray buildings were installed

Correction: Mt. Zion is not “open seven days a week.” Being a Jewish cemetery, it is closed from sundown Friday to sundown on Saturday–the Jewish sabbath.

Acknowledged

One of my ancestors was Richard Betts – who I believe was the last orginal settler.

Of course my girlfrend thought he might be related to ‘Ramlin’ Man’ Dickey Betts. Sheessh!