In March 2022, when FNY presented the baseball streets of Commack in Suffolk County, several streets in NYC also named for baseball players were pointed out to me. Frankly I have always wondered why there haven’t been more of them, as baseball has been an important part of NYC psyche over the years; it’s sometimes thought that when NYC’s baseball teams are doing well, the city itself is doing well. Perception can be different from reality because when the Yankees were on their streak of postseason appearances and two World Series championships from 1976 to 1981, the city was arguably at its lowest ebb and Howard Cosell told the cameraman to shoot toward a conflagration and said, “Ladies and gentlemen, the Bronx is burning.” The Yankees’ last run of championships from 1996-2000 with another one in 2009 came at a time when the city was indeed on an upswing.

I was born in Brooklyn in August 1957 and thus, the Brooklyn Dodgers and I coexisted for approximately one month. I was not athletically inclined as a youth; I could play a little basketball in high school but that’s the end of it. I paid no attention to baseball whatsoever until the light bulb went on in early 1969, when I was 11 years old, and I began watching New York Mets games and got deeply invested, dropping into brief periods of, let’s say, ill humor when the Mets lost. The Mets, as you know, won the whole darn thing in 1969. When I met Art Shamsky a couple of years ago, I remarked to him I thought that’s what would happen every year! With the Mets, how wrong I was.

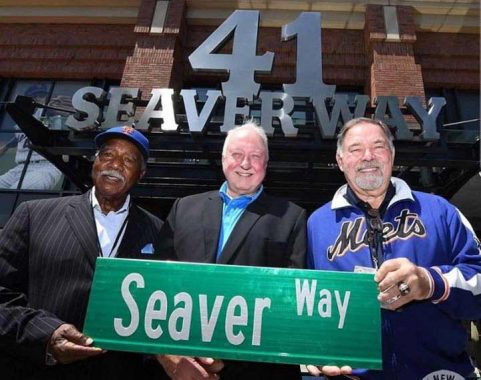

1969 Met teammates Cleon Jones, Jerry Koosman and Ron Swoboda stand in front of the newly christened Citifield entrance, now 41 Seaver Way, and hold a NYC Department of Transportation street sign that is now affixed to a lamppost on 126th Street between Northern Blvd. and Roosevelt Ave. on the east side of the stadium.

The signs honor Fresno, California native, U.S. Marine and Hall of Fame pitcher Tom Seaver, the greatest player the star-crossed New York Mets have ever produced. Playing before the pitch-count era, he amassed 311 victories and 231 complete games, wining the Cy Young Award three times and winning 20 games in a season five times over a 20-year career with the Mets, Cincinnati Reds, Chicago White Sox and Boston Red Sox. His arrival to the Mets in 1967 marked a change in the team’s outlook—formerly an aggregation of other teams’ castoffs, the Seaver-era Mets were renowned for pitching and defense, though making only two World Series and winning one, in 1969.

Yet the Mets haven’t served Seaver’s efforts particularly well. He was traded in 1977, still at the peak of his career, during a contract dispute. After the Mets brought him back for the 1983 season, he was inexplicably left off the Mets’ free-agent draft protected list and was promptly claimed by the White Sox. After the Mets’ new park, Citifield, opened in 2009, former Mets owners Fred and Jeff Wilpon made the grand entrance to the stadium a shrine to Jackie Robinson—a historic major leaguer, but a Brooklyn Dodger. Seaver and other Mets standouts settled for pennants on lampposts outside the park.

Finally the Wilpons decided to set Seaver’s legacy aright in 2019 by commissioning a statue depicting him in action, renaming the stadium address for him as well as petitioning the city to rename 126th Street as Seaver Way. Tom Seaver died of complications of Lyme Disease in 2020, and did not live to see his statue installed on April 15, 2022, at a game I plan to attend. He will have to share the spotlight with Robinson, as all teams celebrate his birthday on that date.

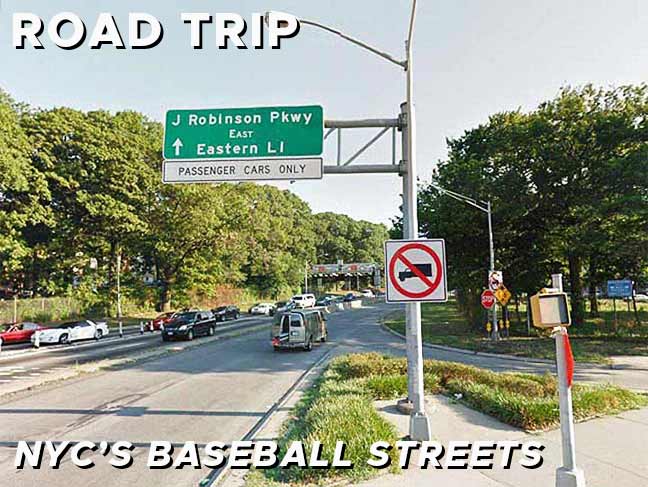

In many ways Jackie Robinson was the most compelling player in major league baseball history. He was selected by Brooklyn Dodgers owner Branch Rickey to break the MLB color barrier in 1947 (no African-American had been employed by a major league team since at least 1901, the beginning of the “modern era” of major league ball) after a sterling athletic record at UCLA, where he had lettered in track, football, baseball and basketball. Rickey needed a can’t-miss prospect, as well as a person who’d be able to endure the inevitable racism that would arise in a sport where many players were from the deep South.

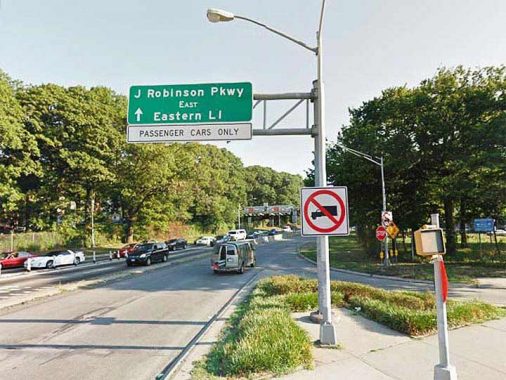

Robinson was a five-tool player who hit for average and power (averaging 16 home runs per year), possessed above-average speed, and was excellent on defense (second base for his early years). Advancing age and diabetes slowed him down in 1956 and 1957; the Dodgers traded him to the Giants, who like the Dodgers were moving to California, but Robinson chose to retire. Robinson passed away in 1972, shortly after addressing a World Series crowd in Cincinnati. He’s interred in Cypress Hills Cemetery, through which passes the parkway later named for him. In 1997 his uniform number, 42, was retired by every major league team, except for players already wearing it; the last one, legendary Yankee reliever Mariano Rivera (see below), retired in 2013.

No borough-wide memorial had been named for him until 1997, when upon the 50th anniversary of his ascension to the Dodgers, New York State designated the entire route of the Interboro Parkway in his name.

For 18 years, playing for the Brooklyn and Los Angeles Dodgers and the New York Mets, native Indianan and first baseman Gil Hodges was the epitome of silent strength, compiling 370 home runs and over 1200 runs batted in, playing impeccable defense for a Brooklyn Dodgers team that repeatedly made the World Series but only captured the ring once, in 1955. Breaking in as a catcher in 1943, Hodges saw combat in World War II, losing two seasons to the war, but hit his stride once he switched to first base. Hodges made the All-Star team eight times, received Most Valuable Player votes nine times and was finally elected by the MLB Veterans’ Committee to the Hall of Fame in 2021, some 49 years after his death.

After his playing career ended in 1963, Hodges turned to coaching and managing, helming the Washington Senators from 1964 to 1967 and the New York Mets from 1968 until his death in April 1972 at 47, overseeing the Mets’ unlikely run to a World Series victory in 1969. Always a heavy smoker, Hodges succumbed on the golf course to a heart attack.

Hodges embraced his status as a Brooklyn transplant and maintained a residence with his family on Bedford Ave. from his Dodgers days until his death. A short stretch of Bedford Ave. between Aves. M and N in Midwood is co-named for him, as was the Marine Parkway Bridge connecting Flatbush Avenue with the Rockaway peninsula.

It’s indeed unusual that so many great Red Sox players later came to the New York Yankees. Baltimorean Babe Ruth was one of the greatest pitchers of his era with the Red Sox from 1914-1919, winning 89 games and leading the Sox to three World Series victories (1915, 1916, 1918). Ruth’s nine shutouts in 1916 set a league record for left-handers that would remain unmatched until Ron Guidry tied it in 1978. He set the World Series record for consecutive scoreless innings, also since surpassed. With their roster depleted due to several players serving in WWI in 1918, the Sox had some holes in the lineup and put Ruth at first base and in the outfield when he wasn’t pitching, and he responded by leading the league in home runs in the so-called dead ball era with 11 in 1918 and 29 in 1919.

When Red Sox owner Harry Frazee balked at Ruth’s salary demands he sold Ruth to the Yankees, who chose to play him in the outfield exclusively (he pitched a handful of games, going 5-0) and throughout the 1920s he and the Yankees led baseball into the modern era with a power and scoring explosion unmatched until the steroid era in the 1990s. At first, Ruth stood alone, outhomering many teams at the time en route to ten home run crowns with the Yankees between 1920 and 1931. He was joined by some of the greatest offensive stars of the era that included Lou Gehrig (see below), Tony Lazzeri and later, Bill Dickey. Ruth consistently had an OPS (on-base percentage plus slugging percentage) of over one, a high mark for any player, never struck out more than 93 times (though leading the league in that category often) and even captured a batting title the year after he lost one in a year he hit .393.

Ruth’s fast lifestyle, poor diet and smoking cut his life short at age 53 in 1948. Though he had won numerous World Series with the Sox and the Yankees, one of his greatest desires, to become a major league manager, was never fulfilled. He has been played repeatedly in the movies by the likes of William Bendix, John Goodman, and in the “Pride of the Yankees” Lou Gehrig biopic, he played himself.

Today, Babe Ruth Plaza can be found on East 161st Street at the New Yankee Stadium west of River Avenue, relocated from the Grand Concourse at East 161st alongside Lou Gehrig Plaza; its beautiful bronze sign was also moved.

Motorists traveling on E. 161st Street wishing to avoid the intersection with the Grand Concourse can travel under a tunnel running between Gerard and Sheridan Avenues. Meanwhile, the area above the tunnel between the Concourse and Walton Avenue is occupied by the newly landscaped Lou Gehrig Plaza, named for the Yankees’ legend.

Born in Yorkville, Gehrig attended Columbia University for two years until signing a contract with the Yankees in 1923. He began his famed consecutive games played streak in 1925, the year incumbent Yankees first baseman Wally Pipp supposedly had a headache one day and Yankees manager Miller Huggins put Gehrig in and he never relinquished the job. The true story is that in 1925 the Yankees were playing poorly—Babe Ruth sat out much of the year with various problems—and Huggins wanted to give the team a spark. Gehrig had come off the bench for parts of two years and was doing quite well in that role until Huggins decided to shake things up halfway into 1925.

Gehrig performed well, but didn’t find his power until 1927, the year of the Yankees’ “Murderers’ Row”; that year he hit .373/47/173/.474/.765, a year that looks superhuman today. He kept this up year after year until 1939, when his ALS, a disease that paralyzes and then kills its victims, manifested itself. Another famed Yankee, Catfish Hunter, was also victimized by the same malady several decades later.

Lou Gehrig Plaza for many years has been marked by a marvelous bronze sign showing Larrupin’ Lou taking a cut. An adjacent plaza had been named for Ruth, with a similar bronze signpost. Babe Ruth Plaza was moved to 161st St. west of Jerome Ave. when the new Yankee Stadium opened in 2009.

Known as the Chairman of the Board for his calmness in tight game situations, Edward Charles “Whitey” Ford (1928-2020) spent his entire career as staff ace with the Yankees during the era of their greatest dominance from 1950 to 1967, taking two years off from 1951-52 while serving in the Korean War. led the American League in wins three times and in earned run average twice. He is the Yankees franchise leader in career wins, shutouts, innings pitched and games started by a pitcher, made the All Star Team eight times and won the American League Cy Young Award and World Series MVP in 1961, winning ten postseason games in all. Born in Manhattan, he moved to Astoria at age five and also later spent several years in Little Neck, my current hometown. Besides Whitey Ford field in Astoria Village, 43rd Street between 34th and 35th Street was co-named for him in late 2021.

Edward L. Grant Highway is one of the few streets in NYC designated “Highway” (Kings Highway is the longest and most famous). Formerly Boscobel Avenue, though it’s in the Bronx not far from Yankee Stadium, it was renamed in 1945 for a baseball player, but not a New York Yankee… Edward Leslie “Harvard Eddie” Grant played in the major leagues between 1905 and 1915 for the Phils, Reds and New York Giants, hardly a superstar but a workaday infielder. He was killed at Argonnes, France in October 1918, three years after his baseball career ended. Grant was the first major leaguer or ex-major leaguer killed in WWI action. In 1921, the Giants dedicated a plaque in the centerfield at the Polo Grounds in his memory; the plaque is duplicated at the Giants’ present home, AT&T Park in San Francisco.

Grant Highway runs northwest from Jerome Ave. and 167th St. to University Ave. (Martin Luther King Blvd.) where it meets Washington Bridge. Not the George Washington Bridge—merely the Washington Bridge, which spans the Harlem River, not the Hudson.

The greatest “closer” in major league history, Mariano Rivera piled up 652 saves during a 19-year career from 1995 to 2013. For those unfamiliar with the term, the “closer” is the last pitcher in a game in which his team wins and to be credited with a “save” he must enter a game with the tying run on base, at bat or on deck and with a lead, or pitches at least one complete inning protecting a lead of no more than three runs. Pitching three innings at the end of the game also earns a pitcher a save.

In 1995 the Yankees brought up a RHP hailing from Panama and started him a few games and the results were underwhelming. In 1996, Rivera had much more success as the 8th inning “setup man” for closer John Wetteland, and beginning in 1997 he was promoted to closer after Wetteland left as a free agent. He became about as automatic as possible and the Yankees were nearly certain to win the game when he pitched the ninth inning. Rarely, he would pitch two innings if the game went into extra innings. Rivera was so reliable that his rare failures over the years, such as allowing a game winning HR to Cleveland’s Sandy Alomar Jr. in 1997 playoff loss, a bloop hit to Luis Gonzalez to lose the 2001 Series or allowing runs to the Red Sox during their historic comeback in the 2004 playoffs, are perhaps more remembered than his successes. He did it all by employing one pitch, a “cut fastball” that is designed and gripped to drop out of the strike zone at the last second, forcing the batter to hit a playable ground ball.

In 2014, the Department of Transportation added an “a” to River Avenue and unveiled a co-naming for one block at East 161st Street honoring the perennial All-Star.

In 2002, a new shopping complex called Gateway Center was built east of Spring Creek, and north of the Belt Parkway and the Fountain Avenue Landfill (since turned into Shirley Chisholm State Park) in what was formerly a marshy no man’s land south of East New York. Big box retailers like Best Buy, Home Depot and Old Navy leased space. Unusually in a masss transit city Gateway Center is inaccessible by subway (similar to Ikea in Red Hook).

Housing was constructed along newly built Vandalia and Schroeders Avenues and Egan Street, which had been on hopeful planning maps for years, and several new north-south Streets were constructed, one of which was Erskine Street, a main artery leading to the shopping center as a new exit/entrance to the Belt Parkway connects it. It was named for a second Indianan to star with the Brooklyn and later, Los Angeles Dodgers from 1948 through 1959, Carl Erskine.

The Brooklyn accent is nearly extinct, but its hallmark was a dislike of the letter R, so that Erskine came to be affectionately called Oisk in Brooklyn. He won 122 games for the Dodgers and two more in World Series games, winning 20 in 1953 and tossing two no-hitters, in 1952 and 1956. During the first one, he had to wait out a rain delay and came back in the game, a rarity in today’s game. He started the first major league game ever played in Los Angeles.

As for other Boys of Summer, Brooklyn has a Snyder Avenue, but it was named long before Duke Snider became the Dodgers’ primary power source. Frankly I’m surprised there aren’t streets at least co-named for the likes of Pee Wee Reese. Speaking of shortstops, NYC will be co-naming a corner in Glendale for Phil “Scooter” Rizzuto, the Yankees’ All Star and beloved announcer for decades.

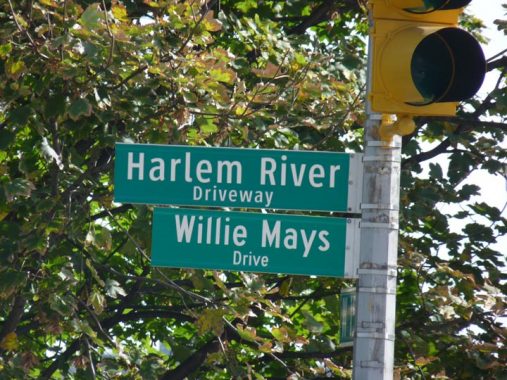

The Harlem River Driveway extends from West 155th Street northeast, funneling traffic to and from the Harlem River Drive proper.

Recognizing the long-standing popularity of horse racing among New Yorkers, the city built a “Harlem River Speedway” along the west bank of the Harlem River in Manhattan. The 95-foot-wide dirt roadway stretched two and one-half miles from West 155th Street north to West 208th Street. Presaging the automobile parkways of the 20th century, the speedway was flanked by trees and pedestrian walkways. When it was not being used as a racetrack, the Harlem River Speedway was used as an exercise track. NYC Roads

When the Harlem River Drive was constructed beginning in the 1930s, it obliterated the old Speedway, except for a short section between what is now the Ralph Rangel Houses (Ralph Rangel, a community worker and tenant association president, was the brother of US Representative Charles Rangel) and West 155th. The extant portion was renamed the Harlem River Driveway.

In 2017 the Driveway was subnamed for New York Giants/San Francisco Giants/New York Mets titan Willie Mays, who played in the Polo Grounds (see below) in 1951, 1952, and 1954-1957, missing the 1953 season during military service. Mays’s son Michael resides in the area and was present at the sign unveiling ceremony.

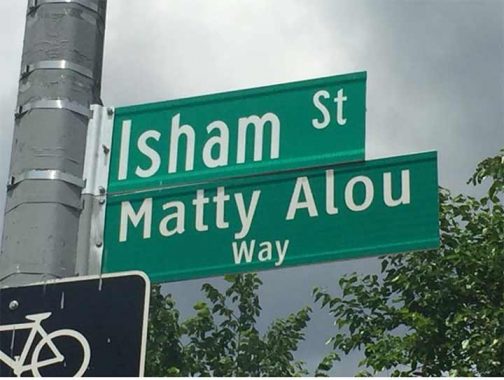

Matty Alou (1938-2011) was a National League batting champion from the Dominican Republic. Though he never resided in New York City, Dominicans in Washington Heights and Inwood point with pride to his accomplishments. He was one of three brothers who had lengthy careers in Major League Baseball, with Felipe and Jesus Alou. All three broke in with the San Francisco Giants and appeared in the outfield together three times.

Matty Alou was a spare outfielder and occasional starter with the Giants until he was traded to the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1966, and he went on to lead the National League in batting with a .342 mark his first season with the team. He played for the New York Yankees in 1973, joining Felipe, who played for the Bombers from 1971-1973. Jesus, meanwhile, was a New York Met in 1975. Felipe went on to become a successful manager with the Montreal Expos, where he had the club in first place in 1994 only to see the season cancelled by a strike.

Matty Alou was rewarded with an honorary street renaming at Isham Street and Seaman Avenue in 2015, four years after his death.

If you’re looking for a successful major league player from northern Manhattan, look no further than Manny Ramirez, who immigrated from the Dominican with his family at age 13. It’s possible that his success with the Boston Red Sox precludes him from being honored on a New York City street sign.

I’ll give honorable mention to the Joe DiMaggio Highway, a name very few people use for what is now the grade-level West Side Highway consisting of West Street and 11th and 12th Avenues between Battery Park and the Henry Hudson Parkway north of West 59th Street. Yankees fan Rudy Giuliani bestowed the name in 1999, but it has only appeared on one or two signs that I can’t locate (let me know if you know where they are).

I’m likely forgetting a dozen “baseball streets” so the Comments are open. I may do a second page later on.

As always, “comment…as you see fit.” I earn a small payment when you click on any ad on the site.

4/10/22

15 comments

Carl Erskine is still around at age 95.

Couple of additional points:

Lou Gehrig, though he was born in Yorkville as indicated, grew up in Washington Heights, where he graduated from PS 132 at Wadsworth Avenue and 183rd Street. Afterward he went to High School of Commerce on 65th Street where his baseball prowess first attracted attention.

In The Bronx, the Mosholu Baseball Field on Webster Avenue between East 201st Street and Mosholu Parkway, is named for Frank Frisch (1898-1973), a Bronx native who was a star athlete at Fordham University. (Source: https://livingnewdeal.org/projects/frank-frisch-field-bronx-ny/). Known as “The Fordham Flash” due to his running speed, Frisch went from the Rose Hill campus directly to the New York Giants at the Polo Grounds. One of the first great switch hitters, Frisch was a Giants infielder from 1919 until 1926. After a dispute with dictatorial Giants manager John McGraw, Frisch was traded to the St. Louis Cardinals, where he continued to star on the field until 1937; he became the Cardinals playing manager beginning in 1934. Between the Giants and Cardinals, he appeared in eight World Series, winning as both player and manager in 1934. Frisch also served as New York Giants radio and TV broadcaster in the late 1940s and early 1950s. His signature phrase was, “Oh those bases on balls,” lamenting pitchers who allowed walks. He was elected to Baseball’s Hall of Fame in 1947.

Frisch died in 1973, due to injuries from a car accident in Maryland, and is buried in Woodlawn Cemetery in the Bronx. His alma mater’s campus is a ten minute walk from his namesake field.

He holds the MLB record for the most hits in the World Series games (58) by a player who never played for the Yankees.

Whitey Ford grew up around that corner, and his father owned a saloon down 34th Avenue between Crescent St. and 24th St. He went to Aviation HS when it was located in Manhattan, but as fate would have it the school moved to Queens Boulevard and 36th St. in the 1950’s, a lot closer to where he lived.

The bar’s name was the Ivy Room

You forgot about Hall of Famer, Rod Carew who was born in Panama, but grew up in Washington Heights, went to George Washington H.S. Manny Ramirez is the second

greatest player to come out Washington Heights.

He isn’t on a street sign.

He darn well SHOULD be, wouldn’t you say? 😉

How about the Firearms related street names by Creedmore?

Creedmoor was once the site of the NRA’s main shooting range that hosted many major shooting competitions. It’s long gone but the street names are evidence of it. More recently an extremely popular rifle cartridge carries on the Creedmoor name.

I don’t know about Whitey in Little Neck, but he lived for years on School House Lane in Lake Success. Willie Mays lived in the 20 story building in Fresh Meadows; he drove a Caddy with Say Hey plates.

I too was always bored senseless by sports except for women’s roller derby on channel 11.

There is a sign for Joe Dimaggio Highway at approximately 64th st on the West Side Highway, along with a sign for the Shipping Terminal.

Ironically, Jackie Robinson has absolutely nothing to do with the New York Mets. His last game was on 10/10/1956 for the Brooklyn Dodgers, and the Mets played their first game on 4/11/1962.

isnt there a street named for thurman munson near yankee stadium