In June 2022 I felt like a walk in southwest Manhattan (I know Manhattan is not often spoken of in terms of “southeast” or “northwest” but…that’s where I happened to be). Desiring a peek at Little Island, which was rather restricted at the height of the Pandemic, I scuttled from the Meatpacking District then down Hudson River Park and would up in Tribeca in the City Hall area. What I look for is a little different from what tourists invading this area are seeking out, so I hope you’ll find something here that’s not what you’ll see in the guidebooks.

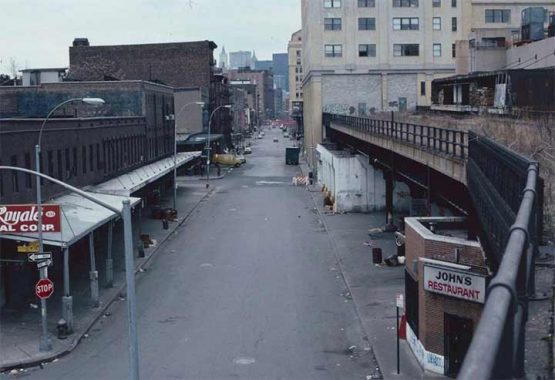

I have been in “The Meatpacking” often since beginning Forgotten NY in 1999. Then, there were more meat wholesalers around but it was beginning its transition into the tourist/shopping mecca it is today. Here’s a fascinating shot I found in the Facebook group New York’s Railroads, Subways & Trolleys Past & Present.

I’ve told this story before about my first encounter with the Meatpacking District. I was working nights at Photo-Lettering in 1983 (a long-defunct typesetting shop boasting the world’s biggest type library). I went into town early one frigid, cloudy December afternoon before work to check out a sci-fi bookstore on 8th Avenue at about Horatio, and something, I don’t know what, led me to head toward the river. I discovered this slumbering metallic railroad behemoth, now High Line Park, then beginning its big sleep following the end of its freight service, and its revival now as an art playground. The neighborhood looked like the photo you see above.

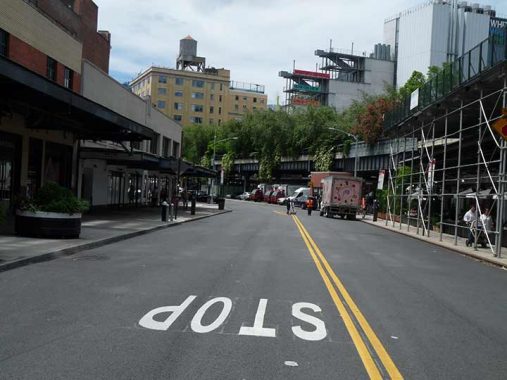

The buildings are still there; the elevated structure is still there; and even John’s Restaurant, now Hector’s Cafe (which I keep meaning to patronize), is still there: but nothing else is the same.

I kicked things off at #29-35 9th Avenue at West 13th Street, a stolid loft building developed in 1903 on land previously owned by the Astor family (along with most of what is now the Meatpacking District). The original tenant was Steinhardt Brothers liquor importers and dealers, but there have been many tenants, including glazed fruits and jellies packers, the Interborough Rapid Transit Co. (the subway’s IRT), electricity generators, binderies, meat packing (naturally).Perhaps the most noticeable former tenant is David Bogen Sound Systems, whose painted ad is still visible on the corner. Bogen was in the building only from 1954 to 1955. The ad is better seen in my 2005 photo that appeared on the cover of the NY Daily News.

In the 2000s, the ground floor was home to the famed Spice Market restaurant, whose space is now occupied by a Rolex Watch showroom.

There were more businesses in what is officially called Gansevoort Market (named for a cross street) than meat wholesalers. Peter F. Collier was a Catholic seminarian who, instead of joining the priesthood, became a salesman for a Catholic book company headed by a P.J. Kennedy, who turned him down on his idea to offer books on a subscription service. Collier went own to form his own company in 1875 and built it into the largest subscription publishing house in America. A magazine, Collier’s Weekly, appeared in 1888 (renamed from Once a Week in 1895) and published continuously until December 1956.

Covers from 1901, 1941. 1948, 1955

From Preservation Ohio:

Collier’s was the main challenger to the dominance of the Saturday Evening Post as America’s favorite household magazine of the era. The name of the magazine was shortened in the first years of the 20th century when the word “weekly” was dropped from the masthead. In the age before electronic media Collier’s was a mix of news, features, tame humor and short stories– a format that is virtually non-existent today. The magazine was also recognized for its art work and illustrations. Among the famous who contributed to Collier’s was Maxfield Parrish – recognized in the early 20th century as the most popular illustrator of the day….

In 1925 the editor of Collier’s sent three reporters on a nationwide tour to look at the effects of Prohibition. They found wide spread corruption and graft within law enforcement and as a result, Collier’sbecame the first national publication to call for repeal of the 18th Amendment. Collier’s lost 3,000 readers but overall circulation shot up by an additional 400,000 new readers.

Circulation of the magazine declined steadily after 1950 as radio, television and the rise of a new generation of national news weeklies – including Time, Life and Newsweek – adapted to the changing national tastes. Compounding Collier’s problems was the television industry which provided less expensive advertising then the magazine could afford. While the Saturday Evening Post exists today in monthly format, Collier’s ceased publication on December 16, 1956.

Collier’s main office was here on the far west side of Manhattan at 416 West 13th Street (though it also had a large operation in Springfield, Ohio after the company was acquired by Crowell Publishing in the 1920s). The company’s symbol, a world globe accompanied by two wings and a torch, still blazes brightly above the door on the shoppers and tourists who frequent this part of town. e.e. cummings worked at Collier’s in 1917 for three months, answering mail. Thousands of books and magazines were produced in the building.

Collier’s was produced here from 1902 (when it was built) to 1929. It’s quite large, and runs all the way through to Little West 12th Street, at an identical facade with a loading dock. After Collier’s moved out, the building was tenanted by General Electric, which had a factory distribution branch here. Handbag and textile firms also occupied the handsome neoclassical building. Today, it’s largely residential with offices and fine goods showrooms, with the restaurant Fig & Olive on the ground floor on West 13th.

In 2016, tech giant Samsung opened Samsung 837 at #837 Washington Street at West 13th, which it calls a ” living lab and digital playground featuring numerous installations and touchpoints,” the better, of course, to pitch its phones and other devices. The company constructed a new tower above an existing former meat wholesaler and, as a nod to the past, actually restored the wholesaler’s sign above the side entrance.

I learned from the Facebook group “Letters of New York” that “Dave’s Quality Veal, 425 West 13th Street, deep in the heart of the meatpacking district [was f]ormerly a butchers and then a sneaker store called Dave’s Quality Meat! Who kept the original sign when they took over in 2003. Founded by Dave Ortiz and Chris Keefe, it was described as the first ever concept store, it was designed to look like a butcher shop, all merchandise was packaged and displayed like meat. They closed in 2008, though the sign is still there.”

Only one small sign on the West 13th Street side of 857 Washington Street marks the place where legendary dive bar Hogs & Heifers, serving both the Meatpacking and biker crowds between 1992 and 2015. A rent hike to $60,000 per month forced out the popular joint. The bartenders and female patrons, who were encouraged to remove their bras and donate them to the rafters, danced on the bar and drink orders were yelled through bullhorns. Sedate retailers now occupy the corner of the venerable century-old brick building, itself once home to meat wholesalers.

Looking south on Washington Street from West 13th. The tower on the right is the new Whitney Museum of American Art, which relocated here in 2015. I haven’t been in yet but plan on attending the Edward Hopper’s New York exhibit scheduled from October 2022-March 2023.

Five meat wholesalers still operate from the Meatpacking District, arranged along West 13th between Washington and West Streets and under the High Line on Washington between Little West 12th and West 13th.

Newsday has provided a handy Meatpacking area chronology:

1851: The city acquires Astor family property, underwater and off Gansevoort Street, to consolidate downtown markets.

1884: Market opens between Gansevoort and Little West 12th streets.

1887: Meat and poultry are added to the district with the West Washington Market.

1900: About 250 meat plants and slaughterhouses thrive in the area.

1934: High Line is completed, originally going as far south as Canal Street.

1949: City builds Gansevoort Meat Market co-op, which survives.

1970s: Club goers mix with meatpackers overnight as a dance, drug and sex scene emerges in the neighborhood.

Late 1970s: Manhattan Storage Warehouse converted to West Coast apartments.

1985: Renowned gay club Mineshaft is shuttered.

1985: Florent restaurant opens, popular with club kids.

Late 1990s: Jeffrey New York leads the way for the arrival of high-end clothing boutiques.

1997: Chelsea Market, built in a former Oreo cookie factory, opens.

1999: Restaurateur Keith McNally opens Pastis restaurant.

2001: About 36 meatpackers remain in the area.

2003: Part of neighborhood is landmarked.

2004: New York magazine declares it the city’s “most fashionable neighborhood.”

2007: Apple’s MePa [yikes — ed.] store opens.

2008: Whitney Museum announces plans for a MePa annex. Florent closes.

2009: First part of High Line park opens.

I have fond memories of Florent on Gansevoort, which had a split personality, catering to club kids by night and as a regular, family-oriented restaurant by day. (I patronized it during the day).

This gate, at the head of what was Pier 54, is the last remnant of a terminal building for White Star ocean liners. Having been preserved by serendipity, it’s now part of Hudson River Park. One of the spectacular ocean liners that used this gate in their heyday would have been the Titanic, though he great liner was due to arrive at nearby Pier 58 — if fate had not intervened. It was there that passengers from the doomed vessel debarked after they were picked up in the icy North Atlantic Ocean by the Carpathia, operated by Cunard.

This is where the RMS Lusitania, the fastest, one of the most luxurious, and second largest liner in the world departed on its final voyage. On May 1st 1915, 1900 people departed Pier 54 for a voyage that would be implanted in the memory of folks for years to come. On the 7th of May, the Lusitania was torpedoed by a German U-boat, sinking in 18 minutes, and taking 1200 victims down with it.

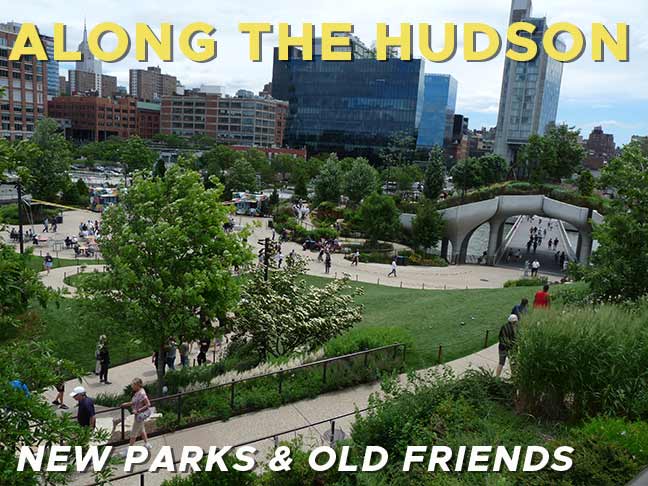

The reason I went to the Meatpacking was that I wanted to get a peek at Little Island, a new park privately funded and built by media mogul Barry Diller and his wife, fashion designer Diane Von Furstenberg. The park is constructed on 132 golf tee-shaped pylons sunk into the Hudson River bed. The park features nature trails, hills, and a 700-seat amphitheater. The park’s design is by Thomas Heatherwick, who also designed “The Vessel,” the climbing structure in Hudson Yards further north.

Perhaps it was because of my mood this particular day, but my feeling about it is a resounding “meh.” The views are good, once you get to the summit of its artificially built hill, but you’re pretty much contained in a pack of people on a narrow trail until you get there. Of interest: I did get a look at Gansevoort Peninsula, a new park under construction at the old waterside Gansevoort Market. The market had its own street system, featuring Bloomfield street and NYC’s 13th Avenue.

I headed down Hudson River Park for my first visit since late 2020. Across the river in Jersey City, south of Christopher StreetI spotted a sculpture of a huge woman’s head and hand making a “shushing” sign. Newport Green Park is a relatively new waterside park created in 2012 along the waterfront. Open to the public, it was built as an amenity for a new apartment complex. The 80-foot-tall sculpture, “Water’s Soul,” was created by Spanish artist Jaume Plensa:

A large majority of Plensa’s work includes sculptures in public spaces. Plensa’s public art installations can be found in Spain, France, Japan, England, Korea, Germany, and Canada. The sculptures are usually over-sized heads, torsos, or spheres. [Jersey City Upfront]

The Holland Tunnel runs beneath the Hudson River at Spring Street and its Ventilation Shaft 2 can be seen just offshore. Two bridges connect it to the mainland, and both feature lighting not seen elsewhere around town. This one is for official vehicles only and is lit by davit-style poles with LED fixtures I can’t identify (help me in comments.) the thin devices at the top of the lamp are meant to prevent birds from landing there and doing what they do.

A public walkway bridge, the remains of former Pier 34, also goes to the shaft, though I presume access to it is locked. It also has davit posts and what appears to be sodium lamps that shine yellow light. Pier 34 formerly served the Clyde-Mallory shipping line, a product of the merger of the Clyde and Mallory lines. If you’re curious, more on these former shipping lines can be found here.

Another lighting hallmark of Hudson River Park is the presence of these retro short versions of Triborough lamps, which first appeared on the bridge in the 1930s. Full size knockoffs can be found on major Queens and Bronx routes such as Broadway, Ditmars Boulevard, Jamaica Avenue and Hunts Point Avenue, though they were originally found on the bridge exclusively and never lit regular grid streets.

Pier 25, at North Moore street, is the largest recreational pier at Hudson River Park and features an 18-hole miniature golf course, sand volleyball courts, a children’s playground with water features and climbing structures, a flexible turf field and a snack bar. There are also the steam powered lighthouse tender Lilac, restaurant ship Grand Banks, and fireboat McKean. When this was a working waterfront, Pier 25 was home to Eastern Steamship Co.

Finding myself in Tribeca at the south end of Hudson River Park, I ducked inland on Warren Street to check on this very special Bishops Crook lamppost, the only one in current action with a Type 6 base (it has a regulation Type 24BC “crook” fixture).

The Crook used to stand on the corner of Warren and Washington Streets; however, Washington Street was mostly obliterated south of Hubert Street in the 1970s-1980s by construction of the first World Trade Center and by PS 234 and Independence Plaza. A short, Belgian blocked stub of Washington Street that led to a parking lot and illuminated by the Bishop Crook remained until the early 2000s. By 2008, construction began on two buildings that would fill the south side of Warren Street: 270 Greenwich and 101 Warren. This left the post at Warren and Washington in jeopardy. It hung tough for a time, but was finally removed.

It had NYC Landmarks Commission protection, though, and thankfully it was restored and placed on the north side of Warren between West and Greenwich Streets. FNY has the complete story, and vintage photographs here.

That’ll wrap it up: as I’ve been saying, I’m trying to keep the Sunday pages shorter. Easier on me, and saves time for you!

As always, “comment…as you see fit.” I earn a small payment when you click on any ad on the site.

9/26/22

5 comments

Southwest Manhattan, right? Not southeast.

What some don’t know that the building that now has the Chelsea Market still has the original name for Nabisco, which was the National Biscuit Company before it abbreviated to what it’s known as now.

The Catholic publisher who didn’t share Mr. Collier’s vision spelled his name “P..J. Kenedy,” one N. Not to be confused with liquor importer, Boston politician and investor P.J. Kennedy, grandfather of JFK. No idea whether One-N or Two-N’s knew each other or ever had any dealings. Two-N’s would have been a youth in the 70’s anyway.

The death toll on the Lusitania would have been even higher if there hadn’t been a number of fishing boats in the area.

That the Lusitania sank in only 18 minutes was the cause for so many fatalities. There was simply no time to launch life boats and move people. The explosion from the torpedo hit was followed by another major explosion, often claimed to be caused by a secret munitions cargo which was detonated by the torpedo strike. This was vehemently denied at the time and for a long time thereafter. Dives to the wreck have not provided further information or clues and the wreck is now collapsing on itself, which will eventually make further investigation unlikely.