TODAY I want to talk about a road running from southern Flushing east to Fresh Meadows, that bears the name of a hospital that doesn’t exist anymore … and was named for that hospital after it was named for a location that it never entered … and before that was named for a creek that now mostly runs in the NYC sewer system. That road, of course, is Booth Memorial Avenue, which goes roughly east-west from College Point Boulevard at Flushing Meadows-Corona Park and the Queens Botanical Garden east to its current east end at the Long Island Expressway and 185th Street. It’s mostly a two-lane road of varying widths. For much of its route, it stands in for 57th Avenue.

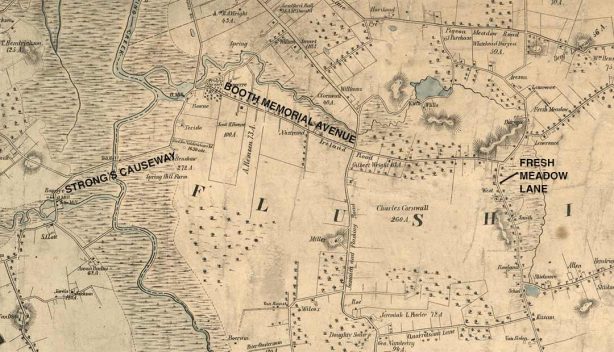

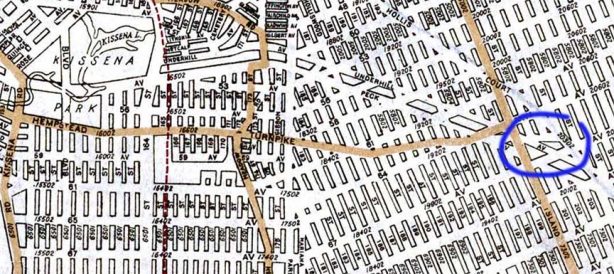

Booth Memorial Avenue has been where it is for a long time. I have marked it on this excerpt from an 1852 Dripps atlas, the Rand McNally or Hagstrom of its era; back then, the only vehicles using it were horses, wagons and carts, as this was a good 25 years before bicycles were invented and a good 40 before automobiles. It was likely a dirt road in the mid-1850s, as only toll roads received wood plank paving at that time. In 1852, the road extended east only as far as Fresh Meadow Lane. Surprisingly enough, most of the old roads in eastern Queens survive in some form today despite the overall numbered street grid that was built in the early to mid-20th Century.

Flushing Meadows-Corona Park is constructed on what were ash heaps (described in F. Scott Fitzgerald’s “The Great Gatsby”) in the north and swampy marshes on the south. Today, crossing the park is possible in only a few spots such as Roosevelt Avenue, the Long Island Expressway, and Jewel Avenue, but before the LIE was constructed in the 1950s, its route was plied by a road called Strong’s Causeway, which crossed Flushing Creek on this iron bridge.

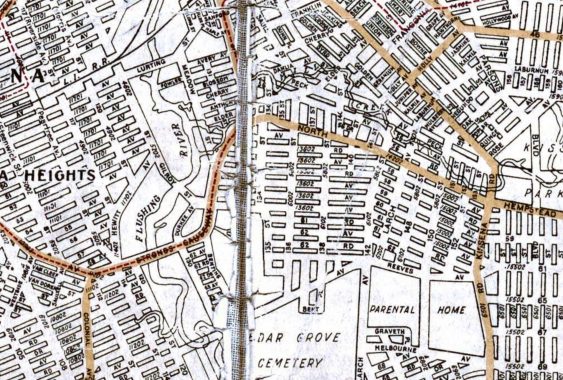

The causeway also supported a trolley line (shown by a dotted line on this 1922 Hagstrom map) that connected Corona (when first developed it was called West Flushing) and Flushing itself. I am unsure precisely when Strong’s Causeway was constructed, but a Flushing Creek crossing, controlled by a tollgate, was in existence as early as 1852 according to the Dripps map. The name could come from Judge Benjamin Woodhull Strong (1781-1847) whose estate, Spring Hill Farm, was located south of the causeway and east of Flushing Creek, where Cedar Grove Cemetery sits today.

On the 1852 map, note the stream running above Booth Memorial Avenue connecting Flushing Creek and KIssena Lake. The stream is unmarked but was called Ireland Mill Creek or simply Mill Creek. The mill itself was located on the west side of College Point Boulevard where it meets Booth Memorial Avenue.

For a few decades, the section of Booth Memorial Avenue between Strong’s Causeway and Kissena Boulevard (on this 1908 map called Jamaica Road) was called Ireland Mill Road, as it paralleled the creek. Today, the creek is mostly in the NYC sewer system beneath Kissena Corridor Park. The section of Ireland Mill Road just east of the causeway was originally renamed Rodman Street and in 1969, became the south end of College Point Boulevard; in the 1960s, as we’ll see, there were plenty of name changes for roads in eastern Queens. East of Jamaica Road/Kissena Boulevard, the road carried the name that eventually would be applied to its entire length until 1964: North Hempstead Turnpike.

Why was there a North Hempstead Turnpike in Queens? After all, the town of North Hempstead is in Nassau County. Well… not always.

The former Queens County Court House (now home to the Queens Supreme Court) in Court Square in Long Island City has been in this location since 1870, and sparked a political dispute that led to the creation of Nassau County.

Long Island counties, beginning in the late 1600s, were Kings, Queens, and Suffolk. Six towns in Kings consolidated in the late 1800s to create the City of Brooklyn, which was annexed (residents voted to consolidate it) to Greater NYC in 1898. Queens’ history is a bit more complicated. Queens originally comprised western Queens (the towns of Newtown, Flushing, Jamaica and in 1870, Long Island City) and what is now Nassau (Hempstead and Oyster Bay; North Hempstead was created in 1784). The eastern towns began agitating for “independence” from Queens County beginning in the 1830s, when a dilapidated courthouse in the Mineola area was to be replaced. Factions from the western and eastern parts of Queens vied for the new courthouse, which was ultimately built in Long Island City at the present Court Square in 1870. Differences, political and cultural, between the east and west ends of the vast county were accentuated during the debate. In the 1890s, proposals for Greater New York did not include Queens’ eastern towns.

When Greater New York was born on January 1, 1898, Queens’ four western towns were politically dissolved and western Queens became a borough. Queens’ three eastern towns remained extant. For one year, January 1, 1898-January 1, 1899, half of Queens County was in NYC, half was not. The eastern towns finally seceded to become the new Nassau County on January 1, 1899.

The first courthouse in this location burned down in 1904, and was replaced with the current Beaux Arts limestone structure in 1908 by architect Peter Coco. The famed 1925 murder trial of Ruth Synder (the smuggled photo of Snyder in the electric chair was a Daily News sensation in 1925) and the robbery trial of Willie Sutton, who robbed banks because ‘that’s where the money is’ were held here.

In 1910, Coco and 13 others were tried for corruption and grand larceny in the very building Coco had designed. He wound up going to prison for 2 years.

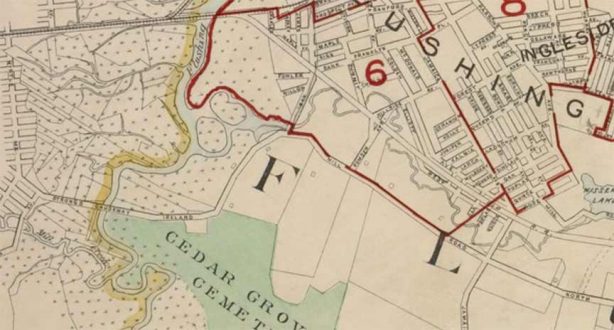

In NYC, it’s been sort of traditional to name streets not where they are, but where they go. When Ireland Mill Road was extended east of Fresh Meadow Road, apparent plans called for it to run as far as Jericho Turnpike/Jamaica Avenue, which indeed went as far east as the town of North Hempstead. However, North Hempstead Turnpike, at its furthest extent east, got as far as Hollis Court Boulevard, amid woods that eventually became Cunningham Park. On this 1922 map, it’s likely that only the streets marked in color existed up to that point. The rest were “paper streets” that NYC and developers later built.

In Brooklyn, note the example of Flushing Avenue, whose east end is in Maspeth, miles from Flushing. However, it connected to a network of roads that crossed Flushing Creek on the toll bridge that eventually became Strong’s Causeway; all trace of the causeway was eliminated by the construction of Horace Harding Boulevard and later, the Long Island Expressway.

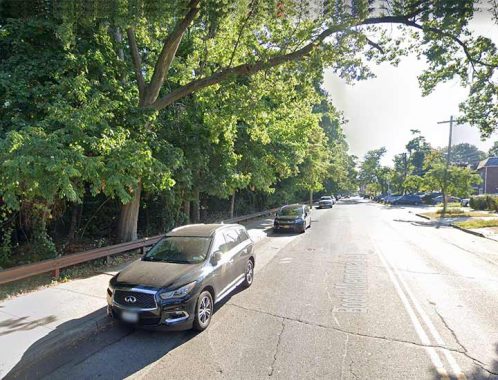

I am unable to walk the entire length of Booth Memorial Avenue at present, so I depended on Google Street View for the images in today’s post. Here we see the west end of Booth Memorial Avenue, where it meets College Point Boulevard.

For a block, between College Point Boulevard and 133rd Street, Booth Memorial Avenue serves as the south end of the Queens Botanical Garden.

It may be smaller than the New York Botanical Garden in the Bronx or Brooklyn’s Botanic Gardens at Prospect Park (Brooklyn, just to be different, loses the -al) but it is no less beautiful. QBG evolved from the “Gardens of Paradise” exhibit at the 1939-1940 World’s Fair, continued after World War II as the Queens Botanical Garden Society. It opened in its current location in 1961. Among the original plantings from the 1939 site are two blue atlas cedars framing a tree gate sculpture at the park’s entrance. Today the park is a 39-acre oasis in one of New York City’s busiest neighborhoods.

Lawrence Street runs for 7 blocks from Booth Memorial Avenue south to the LIE, and there’s another dead-end stub on the south service road. However, Lawrence Street was formerly much longer, as it comprised College Point Boulevard’s entire length from the Whitestone Expressway to Booth Memorial Avenue. It was renamed College Point Boulevard in 1969, for reasons that mystify.

The Lawrence family was prominent in Queens. Captain James Lawrence, raised in Woodbury, then in Queens County, was the captain of the USS Chesapeake when it was sunk in battle by the HMS Shannon in 1813, during the War of 1812. He urged, “Don’t give up the ship. Fight her till she sinks.” Cornelius Lawrence, born in Flushing, was mayor of NYC from 1833-1834, the first popularly elected NYC mayor. He is interred in the Lawrence family cemetery in Bayside, one of two extant Lawrence family cemeteries in Queens, with the other one in Astoria.

Between College Point Boulevard and 164th Street, Booth Memorial Avenue is lined with freestanding and attached dwellings, such as these. Most people who live along the avenue and its side streets have private cars; no subways have penetrated this stretch of Flushing, and the Long Island Rail Road is a couple of miles to the north, making walking to it inconvenient. The nearest east-west bus routes are the Q17 and Q88, both running along the LIE service roads.

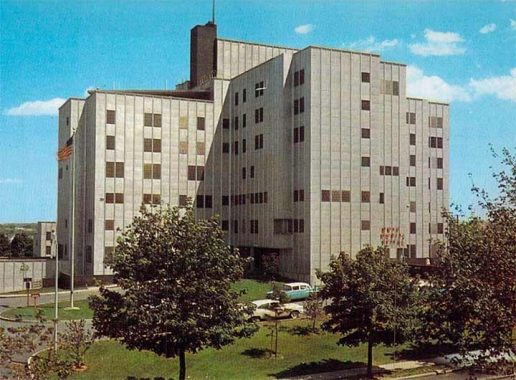

The reason Booth Memorial Avenue has its present name is the present New York-Presbyterian Queens on Main Street. This branch was actually founded in Manhattan by the Salvation Army, as Rescue Home for Women on East 123rd Street. When it expanded its operations to care for injured military personnel and their families, it became Booth Memorial Hospital and moved to 316 East 15th Street in 1919. William Booth (1829–1912), was an English-born, impressively-bearded Methodist preacher who, with his wife Catherine, co-founded the Salvation Army in 1865.

In 1957, Booth Memorial moved to this new campus at North Hempstead Turnpike and Main Street. Additional buildings have appeared since this postcard view appeared the following year. When the Salvation Army discontinued its sponsorship of acute care centers in 1992, Booth Memorial Hospital became an affiliate of the New York Hospital-Cornell Medical Center, and changed its name to New York Hospital Queens, and after New York Hospital and Presbyterian Hospital merged in 2015, it became New York-Presbyterian Queens.

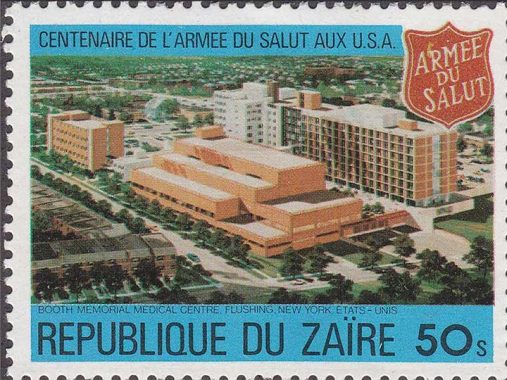

FNY correspondent Sergey Kadinsky: “In 1980, the central African nation of Zaire, now known as Democratic Republic of the Congo, issued a postal stamp on the centennial of the Salvation Army, featuring an aerial photo of the hospital in Flushing. It’s hard to imagine why the authorities in Kinshasa had this Queens hospital in mind. Perhaps a diplomat was treated here.”

In 1964, the city decided to honor the work of Booth Memorial Hospital by renaming the entire length of North Hempstead Turnpike to Booth Memorial Avenue. With the construction of Cunningham Park, Fresh Meadows Houses, and the Clearview Expressway, there was no chance the “turnpike” (I’m unsure if it was ever actually tolled) would ever be extended to Jamaica Avenue to fulfill its “mission” as a connecting route between Flushing and North Hempstead (and by then, the Long Island Expressway was filling that role as best it could, as “the world’s longest parking lot.”)

According to researcher Lawrence Hughes, whose research helped me with this page, in his opinion the name of Booth Memorial Avenue should revert back to Ireland Mill Road. I countered by saying the city wouldn’t change it to a name that sounded so old-fashioned (for me, it’d be cool if we called 73rd Avenue “Blackstump Road” again). Perhaps the name of a recent prominent politician such as the late Queens Borough President Claire Shulman could be honored, but the city would only place additional “honorific” signs adjoining previous Booth Memorial Avenue signs. I believe a more efficacious change would be to simply call it 57th Avenue, as BMA stands in the place of the numbered avenue for its entire length.

Strange Street Names of the Past

I doubt the city would want to disrupt things in eastern Queens, so the situation will stand, with a road honoring a hospital that ceased to exist in 1993.

1938 view of Kissena Boulevard north from North Hempstead Turnpike. Though Kissena Park, on the right, has been cleaned up somewhat in intervening years, and baseball diamonds have replaced the grassland, the southern end of the park still remains wilderness. It was once punctuated by a bridle trail, but the Auburndale stables closed in the early 2000s and have become hiking trails. I should really invade these trails once again; many years ago, I spotted wild pheasant.

A pathway at Booth Memorial Avenue and Parsons Boulevard leads well into Kissena Park, and following it will get you to the Kissena Park Velodrome, the only outdoor bicycle track of its kind in New York City. It was built in 1963 for the Olympic trials held that year. By the 1980s the Flushing velodrome was well past its Olympic trial days in a deteriorated state, and by then was mainly used by kite fliers and toy car racers. In 2003, however, the velodrome was completely rehabilitated, repaved and given a new 400-meter banked asphalt race track and once again is hosting national events. The velodrome can be found by walking or biking a path opposite Parsons Blvd. on Booth Memorial Avenue. The track is named for Siegfried Stern, treasurer for Hartz Mountain pet products and a benefactor for Jewish organizations.

Between Kissena Boulevard and Fresh Meadow Lane, Booth Memorial Avenue’s north side is occupied by Kissena Park and the Kissena Park Golf Course.

Meanwhile, the south side of Booth Memorial Avenue between 164th Street and Fresh Meadow Lane is the north end of Mount St. Mary Cemetery, founded in 1862 as an offshoot of St. Michael’s parish, today located on 41st Ave. in downtown Flushing. Eastern Flushing was farmland at the time, far from the town center at Main St. and Broadway (Northern Blvd.). The pastor at St. Michael’s, Father O’Beirne, procured portions of two farms for the cemetery. There were two later expansions, the latest in 1930, which filled out the cemetery to its present proportions. The Long Island (Horace Harding) Expressway was built on its southern border in the 1950s.

Two figures in rock ‘n’ roll lore are buried in Mt. St. Mary’s, John “Johnny Thunders” Genzale (1952-1991) and Jerry Nolan (1946-1992) both from the New York Dolls, a band that never sold well, but were very influential, or “seminal” as the rock critics say. They were a hard-rocking outfit with outrageous frontman David Johansen, a native Staten Islander who later had hits under a different persona as Buster Poindexter. The Dolls took the stage in drag, but besides that gimmick, their talent was undeniable, and they influenced both the glam and punk eras of the mid- and late-1970s.

Other Mount St. Mary’s interments include Congressmen James Roe, Matthew Merritt, William Barry and Denis O’Leary; Emanuele Ronzoni Sr., founder of the pasta company; and Gambino crime family mobster Louie “The Bone” diBono.

The clubhouse for the Kissena Park Golf Course can be seen from Mt. St. Mary’s. The park had reached its present-day size by 1927 and the golf course appears on maps by 1940.

The park lies on the former plant nursery grounds of Samuel Bowne Parsons, and contains the last remnants of the family’s plant businesses. Parsons Boulevard is the road built in the 1870s that connected Parsons’ farm with that of Robert Bowne. A natural body of water fed by springs connecting to the Flushing River was named Kissena by Parsons, and is likely the only Chippewa (a Michigan tribe) place name in New York State. Parsons, a native American enthusiast, used the Chippewa term for “cool water” or simply “it is cold.” After Samuel Parsons died in 1906 the family sold the part of the plant nursery to NYC, which then developed Kissena Park, and the other part to developers Paris-MacDougal, which set about developing the area north of the park.

Where there’s a cemetery, you’ll find monument dealers. This one is on the NE corner of Booth Memorial Avenue and Fresh Meadow Lane. The FL telephone exchange stands for, as you might expect, FLushing and the number is dialed 357-9248.

Booth Memorial Avenue and Utopia Parkway, which parallels Fresh Meadow Lane and can be seen as a lengthened and straightened version of the older road. In 1905, the Utopia Land Company purchased 50 acres east of the Flushing-Jamaica trolley line (now 164th Street) in today’s Fresh Meadows, planning to build cooperative homes for Jewish people then living on the Lower East Side. The streets were named for several in the Manhattan neighborhood, including Houston, Stanton, Rivington and Delancey. Work had begun, but the company went bankrupt before any housing was constructed, and the region remained woods, meadows and farmland until the 1940s, when the neighborhood was built up by the Gross-Morton Park Corporation with Colonial and Cape Cod-style homes.

Now a part of greater Fresh Meadows, the area’s main north-south main drag, Utopia Parkway, was not completed until the late 40s, replacing the previous main artery, Fresh Meadow Lane, which now fills a subsidiary role. NYC-based rock group Fountains Of Wayne were sufficiently inspired by the fanciful-sounding street to name their second album after it in 1999.

Francis Lewis High School can be found on Utopia Parkway and Booth Memorial Avenue. The school was constructed in 1960.

Lewis (1713-1802) was a Welsh merchant who emigrated to Whitestone, then part of Flushing, in 1734. In the 1750s he entered politics, serving as a member of the New York Provincial Congress, and was later elected as a delegate to the NY Continental Congress in 1775. His mansion was destroyed by the British the following year, aware he supported the patriots’ cause.

In the 1930s, when Cross Island Parkway was under construction, an already-extant road named Cross Island Boulevard renamed Francis Lewis Boulevard. The road was extended south of Jamaica by renaming a number of previously-existing roads.

Morgan Lewis (1754-1844), son of Francis, served in the Revolutionary War and the War of 1812; in between, he was NYDS Attorney General, a State Supreme Court justice, and NYS Governor. Lewis Avenue in Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brooklyn and Lewis Street in Manhattan’s Lower East Side are named for Morgan Lewis.

Today the east end of Booth Memorial Avenue is at the Long Island Expressway just past 185th Street. The road did continue for another mile or so until the mid-20th Century. but construction of the Fresh Meadows Houses and the Clearview Expressway eliminated that eastern section.

What did that now eliminated section of North Hempstead Turnpike look like? These two photographs, taken to chronicle street paving, give some idea. One is of Hollis Court Boulevard looking south from the eastern extent of the turnpike, and the other is of North Hempstead turnpike looking west from the same spot. Neither section of either road exists today, as the intersection is now occupied by the Clearview Expressway within Cunningham Park.

As always, “comment…as you see fit.” I earn a small payment when you click on any ad on the site.

5/7/23

14 comments

Great article. I grew up in Flushing, Queensboro Hill, during the ‘50’s and’60’s To me, the road was North Hempstead Turnpike. Kissena Park our local park.

Another great posting. I lived in Flushing, 1973-78, and have also spent a large part of my life travelling through Queens between residences in Nassau County and a variety of work and non-work locations in Manhattan and Queens. I have driven through these areas countless time, as recently as a week ago. Some additional observations:

1. The trolley line referenced in the initial section about Strong’s Causeway is still an important transit line. It’s now the Q58 bus, which connects Flushing and Ridgewood, using nearly the same route. Despite its Q route prefix, it is part of the Brooklyn bus network, and originates at a garage in Ridgewood on the borough borderline. As a trolley it was part of the privately-owned and huge Brooklyn-based BMT network. It and its sister surface routes passed into the public sector in 1940, when the BMT was swallowed into the NYC Board of Transportation, an MTA predecessor. The route was converted from trolley to bus in 1949, during a period when the Board of Transportation converted every trolley route to diesel buses.

The Q58 is still a busy route today, running 24/7, which service every 8-12 minutes except during the predawn hours.

2. The “Parental Home” on the same map that shows the trolley on Strong’s Causeway is the site of Queens College today.

3. The posting notes how College Point Boulevard was renamed in 1969. Why was this done? Idea was to tie together three different north-south streets that functioned as a through route but changed their names twice because of earlier street networks in the area. Thus, College Point Boulevard was originally College Point Causeway north of Northern Boulevard. South of Northern Boulevard, Lawrence Street continued the journey to Booth Memorial Avenue, where Rodman Street finished up the short stretch to the LIE service roads. All three were re-christened and joined to form College Point Boulevard in 1969. Lawrence Street still runs for 7 blocks from Booth Memorial Avenue south to the LIE.

I had heard that, after it was disassociated with the hospital, the Salvation Army wished to have the name of it’s founder removed from Booth Memorial Avenue, but the request was rejected.

As a reflection of the ever-changing ethnic makeup of New York City, a cricket pitch was installed in place of a softball field a few years ago.

On an another note, the Velodrome was an important part of local social activity back in the 60’s and 70’s. Folks in Brooklyn had the parking areas along the Belt Parkway where young couples could “Watch the submarine races”. In this part of Queens young couples would go to “the bike track” to “watch the bicycle races”.

This excursion across Booth Memorial Avenue resonates. Kissena Park was always a nice place to spend an afternoon. When our daughter was young we’d often go there on Sundays when the Urban Park Rangers led nature hikes (they’d caution us to beware of the legendary snapping turtle). The last time we visited was in 2007 after my father’s funeral; he wasn’t interred at Mt. St. Mary’s, though.We visited our former tenant who had moved to a two-story house on the edge of the park. She seemed to be happy enough but told us she missed us because she’d never have “reasonable” landlords like us again. On our last day before our return to AZ, we visited Mt. Mary’s cemetery where my wife’s side of the family is interred. It would be our final farewell to all our now now-deceased relatives on both sides of the family; I remember buying flowers not too far from

Meriden Monuments. I’ll close with a song lyric:

“Que sera, sera,

Whatever will be, will be,

The future’s not ours to see,

Que sera, sera”

And with things, as they’ve been in the USA for the last three years, perhaps it’s just as well.

I was delighted to be alerted to this post by a friend, since I have long enjoyed this blog, but Kevin has never before come this “close to home.” I have lived on Booth Memorial Avenue since 1957, when my parents brought me here at the age of 5 after I’d graduated from kindergarten in Hollis. I’ve enjoyed living here ever since except for the two unwieldy and paradoxical street names we’ve been struck with.

My preferred solution would be to revert to a shortened version of the original name and make it simply MILL ROAD. Alas, after 66 years here, I am now forced to move, so I can’t lead a local campaign for the name change. But I’d be delighted to see some younger and more energetic person take up this noble cause. The people of Queensboro Hill should not be forced to put up with a street name that is both too long and nonsensical.

Thank you, Kevin, for doing your usual excellent job when you got to my neck of the woods.

I lived in the Mitchell Gardens coop development in North Flushing and in tge mid-sixties went to Francis Lewis HS, don’t ask why. It was a two bus trip, but on nice days I would occasionally bike to school. The most pleasant section of my ride were the parts closest to the school, on 164th St between the cemetery and east on Booth Memorial coasting down past the golf course to the school.

Very interesting! I lived on the corner of BM avenue( I remember when it was North Hempstead Tpke) and Kissena Blvd. I went to Francis Lewis HS. I was told he was a signer of the Declaration of Independence.

I lived on Booth Memorial Avenue and 160th Street from 1961 to 1981, Went to Francis Lewis HS. Have many good memories of Kissena Park.

Kevin, As a lifelong Brooklyn boy, Queens has always been a place where I got lost. My son moved to a numbered street where Long Island City becomes Astoria or vice-versa, with cross-streets that have the same number but are “Places” or “Courts” or “Avenues” or whatever. This sort of grid must have been developed by a masochist. Anyway, as always, thanks for a wonderful visit to a strange land!

A masochist named Charles U. Powell

Great article. I grew up in Fresh Meadows and have always been interested in the local history. Now in Georgia, but it’s fun to learn new facts. The BBC series on the history of art opened one segment with a film of Utopia Parkway when they profiled artist Joseph Cornell. It was strange to see that, say the least.

Not “forgotten “ in the least. Thanks for the trip down memory lane. Great place & time to grow up.

Started on 192nd st and Hollis Court blvd from 61 – 69 then 70 -95 ( with a 6 yr gap ) spent my early thru late teens in and around Kissena /Bowne/ Flushing meadow Corona / Peck / croschron and Cunningham parks . Biking , kegging and the like , You know all the dumb stuff kids did in the 70s . spent time at the Velodrome , Back then it was in a bit of disrepair – Damaged asphalt no seats or guardrails and the surrounding tall reeds served as the local lovers lane . used to bike everywhere ( before my car ) on Booth / The trail from Bishop Reilly HS ( now St Francis ) through Riley woods and along the bike and horse trails all the way to Alley Pond park and Creedmoor Playgrounds . Growing up in Flushing in the 60s and 70s was a great time to be a kid ( then a teen ) . .

The bike paths that you rode were once the Vanderbilt Motor Parkway. It originated at current day Horace Harding Boulevard (the South Service Road) slightly west of the old Bishop Reilly (my alma mater) and continued out to Creedmoor. The overpasses at 73rd Avenue, Hollis Court Boulevard and Bell Boulevard are all original from that toll road.