BY SERGEY KADINSKY

Forgotten NY correspondent

SINCE the demolition of Shea Stadium in early 2009, Forgotten-NY has been documenting hidden train station signs that directed travelers to this former ballpark. With Citibank paying $20 million annually for the Citi Field name, there are a handful of honors for lawyer William Shea. Having campaigned to create a National League team in this city following the departure of the Dodgers and Giants, the Mets organization regards Shea as its founder.

The road bordering on the western side of Citi Field’s parking lot is Shea Road, an honor bestowed after the demolition of Shea Stadium. The city’s multiple agencies recognized that since its construction for the 1939 World’s Fair, this road did not have a name on the map and it needed one to direct motorists and report accidents. Having been informally known as Shea Road, the city made this name official.

The road runs from 126th Street, which is co-named for Tom Seaver, around Citi Field, to its southern end at the Billie Jean King National Tennis Center. There, Shea Road meets Meridian Road, which circles the central core of Flushing Meadows-Corona Park. A few yards before this intersection, it passes underneath the LIRR Port Washington Branch, next to which is the Shea Substation that provides electricity to this train line. The MTA worked hard to erase Shea’s name from its stations; the 7 train and LIRR stations are known as Mets-Willets Point, but this hidden substation continues to honor Bill Shea. It is sandwiched between the tracks and the Olmsted Center, where Parks Department administrators, architects and engineers have their offices.

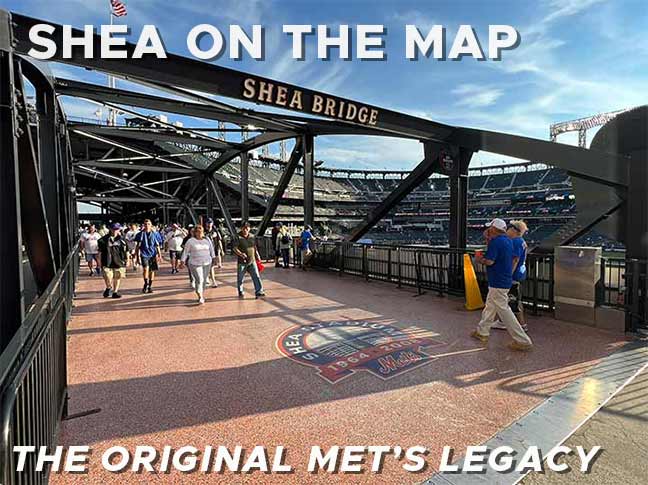

Citi Field is certainly not forgotten, but for a post-millennial stadium, it has its architectural quirks. Numerous fan websites have documented elements that commemorate Ebbets Field, Polo Grounds, the old Shea Stadium, the Home Run Apple, among other things. My favorite item at Citi Field is Shea Bridge, a miniature replica of Hell Gate Bridge behind the bleachers that has a plaque honoring Mr. Shea. The ballpark also has Shea’s name in a medallion on the outfield wall next to the retired numbers of notable Mets players.

Near the Shea Substation is the New Amsterdam Gate to Flushing Meadows. A stele next to this underpass lists heads of state who attended the World’s Fairs of 1939-1940 and 1939-1964. As the world was preoccupied with a global was in 1939, the only foreign leaders who traveled to this park for that fair were King George VI of Great Britain and Anastasio Somoza, founder of a political dynasty in Nicaragua. Among the attendees of the second fair here were three monarchs who later lost their crowns: Mohammed Reza Shah Pahlavi of Iran, Mwabutsa IV of Burundi, and Palden Thondup Namgyal of Sikkim. The last one had a personal connection to this city: his wife Hope Cooke lived in Manhattan before meeting the prince on a trip to India. Following the abolition of the monarchy and Sikkim’s annexation by India in 1975, Cooke returned to New York. She worked as a tour guide, wrote articles about the city’s history, and a book on her experience as a queen. I’m sure she’s familiar with Forgotten-NY.

This city doesn’t have a lot of traffic circles. Kevin documented some of them in 2019. Olmsted Circle honors the landscape architect of Central Park and Prospect Park, among numerous other parks. The building behind it is the Olmsted Center, the only building on Shea Road, but its address is listed as Roosevelt Avenue, as it has been since it was built in 1963 as a temporary office for the World’s Fair administration. In the past decade, the building was expanded and upgraded with sustainability and flood protection in mind.

We usually think that the only remaining structures from the 1939 World’s Fair are the Queens Museum and the Coney Island Parachute Jump. Behind the Olmsted Center is its garage, which was also built for this event. It is used by the Parks Department, unseen by the public. Behind the garage is the world’s largest tennis stadium.

The parking lot for Citifield is one of the largest in the city, bigger than the mega lots of Riis Park and Orchard Beach. Every couple of years we read of plans to build a casino, shopping center, or housing here. But this parking lot is public parkland leased to the Mets. In the off-season it is used for concerts and festivals. If it were to be developed, state law requires compensation by developing new parkland nearby.

I remember when Kevin published an essay on short roads that appeared as boulevards or highways. Shea Road has this look with its median separating the two directions. It is the most visible reminder of William Shea on the map.

Sergey Kadinsky is the author of Hidden Waters of New York City: A History and Guide to 101 Forgotten Lakes, Ponds, Creeks, and Streams in the Five Boroughs (2016, Countryman Press), adjunct history professor at Touro University and the webmaster of Hidden Waters Blog.

As always, “comment…as you see fit.” I earn a small payment when you click on any ad on the site.

7/24/23

12 comments

Supposedly, Citi didn’t want to pony up the money to the MTA to get their name on the stations. whereas Barclays Bank did, and that’s why the subway station at Atlantic Terminal is named “Atlantic Avenue-Barclays Center” (curiously, the LIRR terminal is not so named). It would be a helluva thing if the corporate sponsor for the soccer stadium being built in the Iron Triangle next to the baseball stadium DOES pay the money, and the stop becomes “[Corporate Name] Stadium-Willets Point.”

It’s interesting that there are a lot of places in around the stadium that honor this person. However, I sort of wish that the rotunda was named for someone who really did have a history with the Mets, because Jackie Robinson didn’t, and I’m not saying this out of racism. As for the parking, I have always found it too much to park there, which makes me continue on Roosevelt Avenue to one of the nearby streets even if I walk about a quarter of a mile just avoid those parking prices, and the same goes for Yankee Stadium, Barclays Center, and even MSG, so it’s not just Citifield.

Would I pay $30 to park at Citi Field? Nah. I’d rather park a couple of stations away, than take the 7 Train to the game.

Lucky for me I’m able to find a space just after the GCP overpass, though there were some times I parked around 103rd St-Corona Plaza station and took the 7 to the stadium when that wasn’t the case, plus the parking there is now $40.

Expanding the parking lot size sweepstakes to the suburbs, it would be interesting to see how the Citifield parking lot compares to the southside lot at LIRR Ronkonkoma station. Hard to tell.

When Citi Field first opened it could easily have been mistaken for a Dodgers facility. Wilpon grew up a Dodger fan, and the stadium looked more like a love letter to them than a park for the Mets. It took a good number of years for them to finally celebrate the Mets and their history.

The original home plate sits in said

Parking lot, exactly where it was in shea’s old footprint.

Actually, the story of how Bill Shea got the NL to accept an expansion team in New York is very interesting. When the Giants Board of Directors held a vote on whether to follow the Dodgers to California, there were only two “no” votes – they belonged to Joan W. Payson and M. Donald Grant. After the Giants and the Dodgers left, Payson contacted her good friend and attorney, Bill Shea, to see if they could get another NL team to move to NY. He contacted the owners of the Phillies, the Cubs and the Pirates to see if they wanted to move to NY. No go, When the AL announced that it would be expanding by two teams for the 1961 season, Shea petitioned the NL to also expand into NY for the 1962 season. The NL refused, saying that with the Yankees being as successful as they were, there was no market for an NL team in NY. So Shea concocted a scheme – he announced that he was going to create a new third major league,

called the “Continental League”. This league would be populated by teams in cities that had no presence in the NL, like Dallas-Fort Worth, Phoenix and

Denver. New York would be the flagship franchise. He made no secret of the new league’s intention to raid the NL of its best players. The NL grew concerned that Shea would actually make a go of the new league and capitulated – they told Shea that if he dropped the Continental League, the NL would

expand into NY for 1962. Irony is, Shea never really intended to form the Continental League – it only existed on paper. But he got the results he wanted.

Regarding the honoring of Jackie Robinson in the rotunda, it can be said by this Mets fan since 1967 that old Brooklyn Dodgers players were nearly always present for Old Timers Games and other events at old Shea. While the Wilpons (rightfully in my view) get criticised for the initial lack of Mets historical references back when CitiField first opened, they recognized and made up for it subsequently. Also, Major League Baseball has honored JR by retiring his uniform number 42 for all times, and sets aside a day when all players wear 42 to honor him and what he representing by Branch Rickey selecting him so the Dodgers became the first team to field a Black man. Back in the 1960s and into the 70s and beyond, plenty of Mets fans remembered their old favorite players and NL teams that left New York. Regularly those Mets-Dodgers and Mets-Giants games would approach sell-out attendance at 55,000+ Shea. Now that Seaver, Koosman, and other Mets have been honored by numbers being retired and statuary being dedicated, I feel that the various Mets ownerships — past and present — can look back and feel that they did alright by the fans. It’s just an opinion, but feel free to comment.

For those who may not know, the bus depot nearby was renamed in honor of Casey Stengal, who was the first manager of the Mets.

The LIRR has an interlocking (which controls switches and signals) just west of the station and it is still named “Shea.”

Really enjoyed reading about the hidden layers of history around Shea Road and Citi Field. It’s fascinating how places we pass by every day hold stories waiting to be discovered. For anyone who loves exploring lesser-known spots with rich history, offbeat travel experiences like a Bhutan tour can offer similar surprises: https://northbengaltourism.com/bhutan-tour-packages/.