By SERGEY KADINSKY

Forgotten NY correspondent

ONE of the greatest art museums in the world is hardly “forgotten” and nearly every inch inside and around this structure has been documented in detail. If one knows where to look, there are hidden elements in the Metropolitan Museum of Art that are known only to the consummate New York historian.

The Fifth Avenue sidewalk in front of The Met was redesigned in 2014 and named for trustee David H. Koch, who donated $65 million to this project. It reduced the fountains on either side of the entrance stairs and planted rows of little leaf linden trees to make the museum’s front side pedestrian-friendly, park-like, and environmentally sustainable.

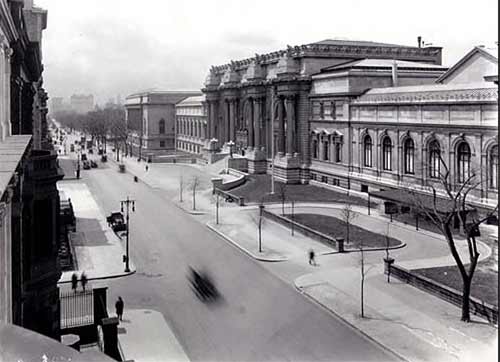

Prior to the Koch redesign, the plaza was mostly concrete and bricks with a long fountain row. It appeared cold and uninviting. That modernist look dated to the 1970s. Going back further to 1925, we see driveways at this plaza and a much smaller staircase at the entrance.

|

|

|

|

|

|

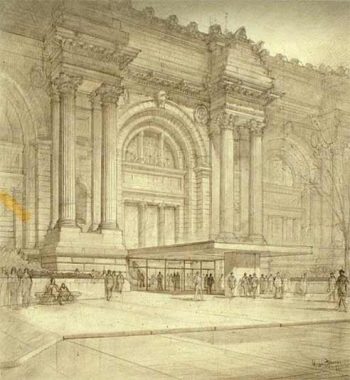

Automobiles have done a lot of damage to the city’s fabric with highways tearing through neighborhoods and parking lots occupying open spaces. In the 1940s the museum’s trustees expected more visitors to arrive by car and commissioned architectural illustrator Hugh Ferriss to design a ramp in place of the grand staircase. At the time, its sister institution, the Brooklyn Museum, had removed its front stairs in favor of a street-level driveway. The American Museum of Natural History has its driveway hidden beneath the entrance staircase.

A decade later the trustees had another idea, to remove the stairs entirely in favor of a street-level entrance featuring a glass lobby and tongue-like ceiling. Escalators inside would have brought visitors to the Great Hall. Fortunately this Ferriss design also did not go beyond the pencil sketch. In 1967 museum president Thomas P.F. Hoving had the opposite idea, hiring architects Kevin Roche John Dinkeloo & Associates to expand the grand staircase, giving New Yorkers their biggest stoop.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Stylistically, it fits with the beaux-arts facade and I cannot imagine the museum without it. In contrast to European museums, many of which are former palaces, The Met does not face a giant plaza or boulevard. Calvert Vaux proposed a widening of Fifth Avenue in front of the museum, but this plan did not proceed beyond the drawing.

Looking east from these steps is East 82nd Street and the landmarked Benjamin N. Duke mansion. Atop the double columns are pyramidal set-ups of rough hewn stones. They’re placeholders for statues that never arrived. To see examples of completed statues atop beaux-arts columns, visit the New York Public Library in Midtown.

Looking up from the steps at The Met’s facade are roundels of six masters: Raphael, Michelangelo, Durer, Rembrandt, Bramante, and Velazquez. The beaux arts design by Richard Morris Hunt is a contemporary of the New York Stock Exchange, Grand Central Terminal, and the General Post Office, civic monuments of the early 20th century that evoked the glory of classical civilizations.

Hunt’s facade is an expansion wing completed in 1902 that hides the original museum building from 1880. Its Ruskinian Gothic design echoed other buildings in Central Park and its entrance was inside the park rather than on Fifth Avenue. There are two places where visitors can see the walls of this building enveloped by galleries of the expanded museum. Since its opening in 1875, its footprint has expanded 20 times.

The lobby separating the original building from the Robert H. Lehman wing provides views of the exposed striped arches from the Victorian period. As for the Lehman wing, it was built in 1975 to accommodate its namesake’s sizable collection that was donated to The Met, resulting in the expansion of its footprint into Central Park. Topped by a pyramidal atrium, its appearance reminds me of the Museum of Jewish Heritage at Battery Park. A second spot where the pointed arches are exposed is on the second floor hallway in the Drawings and Prints section.

In this museum, even a staircase can be a work of art. Deep inside its oldest wing is an original staircase with multifoil roundels designed by Jacob Wrey Mould. In architectural jargon, circles with five lobes are cinquefoil, four are quatrefoil, three are trefoil. Six and above are collectively known as multifoil.

The museum’s first expansion was between 1888 and 1894, with a main entrance on its south side entering a red brick building with rounded arches. That old entrance now connects to the European sculpture court, best known for Rodin’s Burghers of Calais. This entrance originally faced a driveway connecting with East Drive in Central Park. By the time it was completed, the expanded museum was already too small as its collection continued to grow. In the following year, renowned architect Richard Morris Hunt produced a beaux arts design that includes the Great Hall and main entrance on Fifth Avenue. His plan was then expanded upon by McKim, Mead & White in the early 20th century. The Renaissance-inspired wall that faces the old entrance suffered delays and was completed in 1990 as the Kravis Wing.

Most New Yorkers do not have great views of the city from their windows. That’s why we walk the bridges, stare out of the windows in elevated trains, and visit observation decks atop skyscrapers. The rooftop deck at the Metropolitan Museum offers views of Central Park, the skyline of Midtown, and during my visit, a LA-inspired sculpture by Lauren Halsey. The Roof Garden is a small portion of the museum’s total roof space. Most of it is occupied by glass panels that filter natural light down to the galleries.

Between the panels and the translucent glass atop gallery rooms are the attic spaces accessible to museum staff. Looking at aerial views of the museum, there is room to expand the public space here, install solar panels, and vegetation. For a comparable experience, the Whitney Museum also has an accessible rooftop.

As mentioned earlier, the staircases at the museum do not receive as much attention as paintings and sculptures. The stairs connecting to the roof are covered in mirrors in the style of the 1970s. This staircase also leads to the fourth floor, which has the Patrons Lounge and dining room.

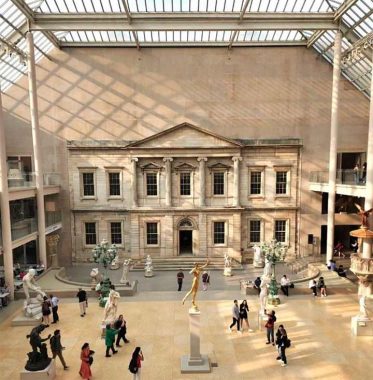

The Met has a number of interiors transported from other locations, and buildings reassembled from half a world away, such as the Temple of Dendur. They’re certainly not forgotten. Less known to visitors is the Federal-style facade in the American Wing which relates to local history. Constructed in 1824 at 32 Wall Street, this building initially served as a branch of the Bank of the United States and later as the Assay Office. Facing demolition in 1915, its facade was saved and reconstructed within The Met.

When it was reconstructed in 1924, this building faced an outdoor garden as envisioned by Hunt and completed by McKim, Mead & White. In 1980, the Charles Engelhard Court was enclosed in glass, sheltering it from the elements with a climate-controlled environment. Described by the New York Times as a “crystal palace” in a nod to an earlier historical structure, it contains other salvaged New York architectural items: a pulpit from an Upper West Side church, a statue from the original Madison Square Garden, lampposts designed by Hunt, and stained glass windows from a Brooklyn church.

One artwork that the museum famously sought after but did not receive were the two Art Deco friezes from Bonwit Teller that Donald Trump promised to The Met in 1980, but then had them quickly destroyed. Surely the museum can commission replicas of these beloved sculptures. I have my own tribute to these friezes here. To see a museum with an outdoor sculpture garden within its walls, visit MoMA.

An example of a replica can be seen in Gallery 305, the Medieval Hall. The Deesis Mosaic was created in the Hagia Sophia by the Byzantines, then covered up by the Ottomans, and partially revealed in the 1930s when that great church-turned-mosque became a museum. Like the mosaic, this painted replica shows only the portion revealed on the original artwork. Two things fascinated me about this gallery: the staff-only platform below this replica, where does it go?

I also know that the Medieval Hall was once a freestanding building- the original museum structure whose Romanesque interior was given a medieval makeover in the 1930s. Opposite of the Deesis Mosaic replica is the choir screen from Valladolid, which serves as the backdrop to the museum’s Christmas tree and in 1963, for the last time that the Mona Lisa was brought to this country.

Because it was the longest lasting successor state to the Roman Empire, there is much public fascination with the Byzantine Empire. Underneath the Great Hall Steps of the museum are exposed brick arches that contrast with the limestone and concrete seen throughout The Met. These bricks provide a sense of authenticity as that empire built many of its churches out of brick to provide a sense of security during the instability of the Middle Ages.

It is common for museums to have a few of their artworks outdoors as a preview of the larger collections inside. The only sculpture in The Met’s collection that is outside of its building is Isamu Moguchi’s 1979 work Unidentified Object, located at the entrance to its public garage. Queens residents know him well. His former studio-turned-museum is in Long Island City. To my surprise, the underground garage has no art on display. Considering its wall space, I can imagine mosaics, replicas of cave paintings, and murals beautifying this space.

There are only two public entrances to this museum, atop its front steps, and on the ground level through its Center for Education. Likely for security reasons, the exit facing Central Park is kept closed. The only item of beauty here is the reflection of the Obelisk on its glass facade. Although the oldest sculpture in the city belongs to the Parks Department, there is a sense of connection between it and the museum. I can imagine this space beautified with sculptures on the lawn and reliefs on the wall here.

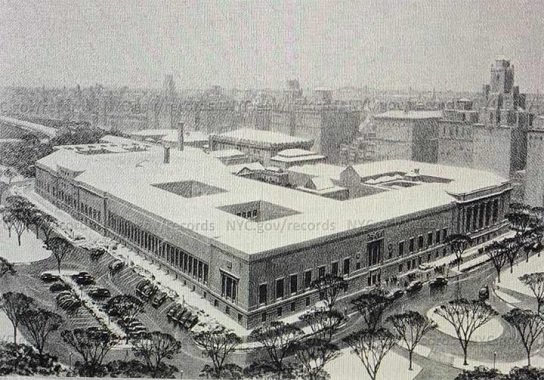

The mix of architectural styles in the museum’s wings could have been simplified with this proposal from 1944, which envisioned a facade of columns facing the park. But it also included a parking lot on parkland that fortunately did not become reality.

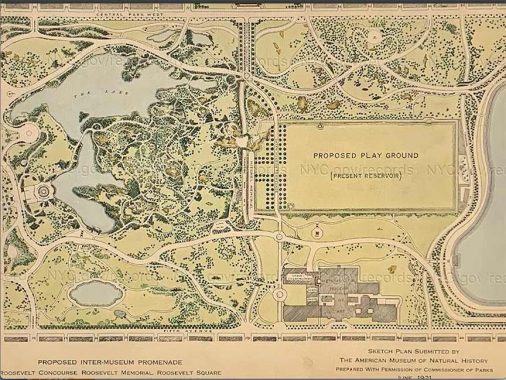

This parking lot was a modest intrusion into the park in comparison to 1921, when the American Museum of Natural History proposed a promenade through Central Park connecting it with The Met. Underneath Vista Rock and Belvedere Castle it included a memorial to Mayor John Purroy Mitchel, which was instead built further north near East 91st Street. Concerning the museum on the other side of Central Park, I have a detailed essay on its expansion too.

My familiarity with the Metropolitan Museum of Art comes from my work as a tour guide and art history professor at Touro University.

Sergey Kadinsky is the author of Hidden Waters of New York City: A History and Guide to 101 Forgotten Lakes, Ponds, Creeks, and Streams in the Five Boroughs (2016, Countryman Press), adjunct history professor at Touro University and the webmaster of Hidden Waters Blog.

As always, “comment…as you see fit.” I earn a small payment when you click on any ad on the site.

7/30/23

8 comments

The Obelisk did have actual hieroglyphics on it, but because it wasn’t used to the temperatures of NYC when it was first brought over, they faded away, though there are attempts to restore them.

Thats just not like Trump to do something like that

Chris: I agree. I wasn’t aware of this slanderous accusation, but if it involves Bonwit Teller & our favorite former president, I suspect that a certain demented former magazine editor may be the source of further treachery.

https://rashmanly.files.wordpress.com/2019/06/fullsizeoutput_33ae.jpeg?w=768&h=499

The oddity is that either the driveway proposal or the ground-floor entrance proposal would have made the Fifth Avenue entrance more “accessible” than the stairs are as a main entrance, though I’m sure that neither proposal had this consideration foremost in mind.

When I was 6 I got it into. my head to go see the obelisk in Central Park(also called

Cleopatra’s Needle)It was a overcast day in the late afternoon in the Fall and there

was no one else around.The thing creeped me out.I think it was those crabs at the base

of it that did it.They looked like monsters.Remember in “2001” when the chimps go

ape-shit over that big black monolith?Exactly.

It really happened and the link you posted has nothing to do with the Bonwit Teller friezes.

Oh, there you go again. Stop getting stuck on stupid. “It really happened…” Show us the evidence. As for the link I posted: I’m not surprised by your reaction to it because you are humorless. Wake up: Urban America is

dying. What will you do when MOMA becomes another shelter for the illegals your mayor can’t cope with & your governor ignores? Here’s something else to consider if you’re willing:

https://nypost.com/2023/08/01/mayor-eric-adams-has-messed-up-the-migrant-crisis-in-nyc/

Your comment has absolutely nothing to do with my essay on the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Also, you’re hiding behind anonymity. Show yourself!