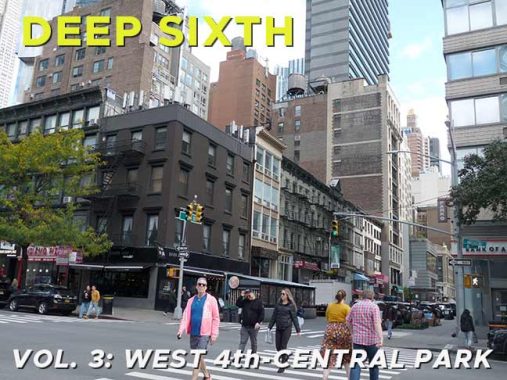

IT’S been two decades since I first walked 6th Avenue for FNY, and things have changed along the avenue in the center of Manhattan (in “The Ferrari in the Bedroom,” humorist Jean Shepherd went so far as to call it the “armpit” of Manhattan). Finally feeling free after months of not being able to walk much prior to hernia surgery, in mid-October I walked from the West 4th Street subway all the way up 6th Avenue to Central Park. I gathered 113 photos; in the previous page, I was able to recount my trip as far as 24th Street before tiring.

“Nothing But Flowers.” Manhattan’s dwindling Flower District is one of a number of subneighborhoods in Manhattan I refer to as “fiefdoms.” Walk down West 28th Street between 6th and 7th, and on Sixth between 27th and 28th. The sidewalks on both sides of the street are full of billowing fragrance and you’re greeted with flowers in every color of the spectrum; trees, bonsai, bamboo and grass.

The Flower District had its beginnings as far back as the 1870s, when flower dealers congregated near the East 34th Street Ferry. In those days the Long Island Rail Road had its western terminus in Long Island City and many goods, including those from the flower farms of Long Island, were shipped across the East River. In the 1890s, though, the flower wholesalers moved here, in an area concentrated on 6th Avenue between West 26th and West 29th, to serve the theater and entertainment area, which was here at the time, as well as nearby Ladies’ Mile (between 14th and 23rd) 5th Avenue hotels…and the brothels of the Tenderloin District, of which 6th and 28th was the epicenter.

Imagine my wonderment in the spring of a year almost comically remote (1981) when I staggered uptown from a publishing job at 5th Avenue and 20th Street and suddenly found this block. During that time, there were more tons of flowers changing hands in these two spare blocks than anywhere else but Amsterdam, Holland. I recall the George Rallis storefront from when I worked on West 29th Street between 6th and 7th from 1988-1991.

I shot the NE corner of West 28th with 6th Avenue from two slightly different angles, so I could get the King of All Buildings in one of them. The corner building shown here appears new, but it iscatually a century or so old and had all its external ornament stripped away to match current bland conventions. The tall building at the rear is the new Ritz-Carlton NoMad a block away on Broadway, which used to be a boisterous, swirling maelstrom of import-export shops and printers between Madison and Greeley Squares. It is mostly closed to auto traffic now so trucks cannot unload goods, and the wholesalers are disappearing. But that’s a story for another page.

This is also the west end of Tin Pan Alley, a maelstrom of a different kind, the epicenter of songwriting in NYC in the early 20th Century; George Gershwin sold Fred Astaire songs here when Fred and sister Adele were a fledgling song and dance act, and the William Morris Agency was located here in its early days. Music and showbiz history was made at 45 West 28th, now the home of a nondescript wholesaler. Here George Gershwin worked from 1914-1917, with Fred and Adele among his music customers. adjoining No. 43 was the home of the William Morris Agency beginning in 1903.

Tin Pan Alley is marked by a DOT street sign on Broadway, as well as a brass plaque on the sidewalk at the SE corner of Broadway, now, er, forgotten by all. The Tin Pan alley link above will give you a glimpse of what 6th Avenue looked like in 2008, and there have been some changes made since.

6th Avenue’s west side between West 28th and 29th. These buildings from the turn of the 20th Century’s lives are likely numbered. Superior Florist, and its neon sign, where there when I worked in the area between 1988 and 1991.

West 29th Street and 6th Avenue is pretty much the southeast end of the Garment District, a much larger “fiefdom” than the Flower District, and it’s here that on the older buildings you see painted ads advertising the garment wholesalers once ensconced inside. In many cases, they weren’t ensconced for long; however, the ads used a high grade of paint and so are still readable over a century after being painted.

As always, we turn to the Indispensable Walter Grutchfield:

The Maid-Rite Dress Co. was formed in 1920. As described in Women’s Wear, 13 May 1920, pg. 16, “The Maid-Rite Dress Co. is a new firm located at 162 West 21st street, manufacturing a line of tricotine and serge dresses. All designing is done by Joseph S. Zanfini, a member of the firm, who was formerly designer for the International Dress & Skirt Co. The other members of the firm are Herman S. Kohn and Jacob Adelman. For the past three years Mr. Adelman has been conducting his own dress factory. The fall line is ready and the following salesmen will soon leave for their respective territories: Julius Bearnheimer, South; Al Engler, the Middle West, Adolph H. Kulka, Washington city and the States of Pennsylvania and Maryland, and Julius M. Wile, New York and the New England States.”

Maid-Rite moved from 21st St. to 29th St. a short while after formation: “The Maid-Rite Dress Co. has moved from 162 West 21st street to the new building at 40 [sic] West 29th Street, where the firm has leased the entire fourth floor, and fitted up a showroom as well as modern stock and shipping rooms. All manufacturing will be done in the spacious new quarters. The initial showing of the Maid-Rite fall line, consisting of dresses in tricotines, satins and serges, designed by Joseph S. Zanfini, will commence tomorrow morning” (Women’s Wear, 12 July 1920, pg. 16).

The Maid-Rite Dress Co. was located at 45 W. 29th St. from 1920 to 1921. An inaugural ad for Maid-Rite ran in Women’s Wear, 13 July 1920. This one, July, 1921.

Regarding the Harris Suspender Co.:

The Harris Suspender Co. derived from the Wire Buckle Suspender Co. consisting of William Silverman, Charles R. Harris, Joseph E. Austrian, and William Freeman in Williamsport, Penn. in the 1890s. Harris was also involved in the Cygnet Cycle Co. manufacturing bicycles in Williamsport around the same time…

This new version of the company moved to 50 W. 29th St. in 1938 and stayed until 1942. Like the earlier version, they then moved to two Broadway locations, with remarkably similiar addresses: 644 Broadway (1942) and 1239 Broadway (1946). This second version of Harris Suspender went out of business around 1948.

I have some pangs of nostalgia for most places I have worked, even where I was mistreated such as Macy’s (2000-2004). With that in mind here’s a look at West 29th at 6th Avenue. I reviewed this block in depth in 2011, and also noted it in 2017.

Greeley Square is the wedge of territory between Broadway and 6th Avenue north of West 32nd Street. It was named for the famed 19th Century newspaper editor, Horace Greeley, who according to popular legend advised young people seeking their fortunes to “go west, young man.”

The reality is more complicated.

Horace Greeley, the son of a New England farmer and day laborer, was born in Amherst, New Hampshire in February 1811. The economic struggles of his family meant that Greeley received only irregular schooling, which ended when he was fourteen. He then apprenticed to a newspaper editor in Vermont, and found employment as a printer in New York and Pennsylvania. Seeking to improve his prospects, he gathered his possessions and a small amount of money, and in 1831, set out for New York City. The twenty-year-old Greeley found various jobs, which provided some capital, and in 1834, he founded a weekly literary and news journal, the New Yorker (not the modern-day weekly).

Greeley founded the NY Tribune (the paper later absorbed the Herald) in 1842 and edited it until his death in 1872. He was an ardent abolitionist and an advocate for women’s rights (though he did not advocate women getting the vote), and workers’ rights. In so many words he told those afflicted by the Panic of 1837 to “go west, young man, and grow with the country.”

Assisted by a talented and versatile staff, a number of whom were identified with the Transcendentalist movement, Greeley made the Tribune an enormous success. It merged with the Log Cabin and New Yorker, expanded its staff and circulation throughout the 1840s and 1850s, and by the eve of the Civil War had a total circulation of more than a quarter of a million. This number, however, vastly understated the paper’s influence, as each copy often had more than one reader. The weekly Tribune was the preeminent journal in the rural North.

Greeley served in Congress for 3 months in 1848-1849, but ran unsuccessfully on numerous occasions for the House and the Senate.

His final campaign was for the Presidency in 1872. He was ridiculed for advocating leniency for the south, equal rights for whites and blacks and thrift in government. He was caricatured by Thomas Nast, who was also waging war against Boss Tweed at the time. Greeley lost to Ulysses S. Grant by a wide margin. He lost control of the Tribune to a rival, Whitelaw Reid.

He soon fell deathly ill. When Reid went to see Greeley, the editor exclaimed, “You son of a bitch, you stole my newspaper!” Years later Reid was asked what Greeley’s final words were. He said “I know that my Redeemer liveth.” Sculptor Alexander Doyle’s Greeley memorial is the second of two Greeley statues installed in New York City in a four-year span, 1890-1894. The editor is in repose in Green-Wood Cemetery.

Above is seen the Hotel Martinique, which has been swaddled in construction netting, but we are finally vouchsafed a peek in late 2023. Henry Hardenburgh’s Hotel Martinique was built in 1900 and expanded greatly in 1910. Its own restaurant was modeled after the Apollo Room of the Louvre featuring walnut panels and wainscoting and paintings depicting Louis XIV and his courtiers. The hotel was not named for the Caribbean island but for its original owner, William R. H. Martin. (R.H. were popular initials around here — Rowland Hussey Macy’s giant emporium moved to Herald square in 1902.) After a stint as a homeless shelter, the Martinique was revived as part of the Radisson chain.

Just a block away, on West 33rd, is Greeley Square’s other great hotel, the McAlpin. It was constructed in 1912, the year the Titanic went down, 2 years after Penn Station opened, and it was at the time the world’s largest hotel. It is presently called the Herald Towers and holds condominiums and retail on the ground floor. Its Marine Grill boasted several colorful terra cotta murals of maritime scenes. Thankfully they were saved and placed in the Fulton Street complex of subway stations downtown on Broadway.

Broadway is shown here at Herald Square, where it meets West 34th Street and 6th Avenue, one of the busiest intersections in a city full of them. However, car and truck traffic is now missing from Broadway; the Department of Transportation officials have been putting Broadway on a diet, as far as lanes open to automobiles go, and have even completely closed off certain sections. These movable tables and chairs are placed elsewhere during special events such as the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade.

Herald Square is named for a long-defunct newspaper, founded in 1835 by James Gordon Bennett Senior, who made it the most widely-read and profitable newspaper in the country. He ceded operations to his son James Gordon Bennett Junior in 1867, who continued the paper’s popularity while resorting to fabrication on occasion: the paper falsely reported in 1874 that the inhabitants of the Central Park Zoo had escaped and were causing a ruckus. The paper funded the famed African expedition of Henry Stanley to locate explorer David Livingstone. After Bennett’s death in 1924, the Herald was acquired by the New York Tribune. The Herald Tribune lasted until 1966 when a printers’ strike put it out of business.

There is still plenty of the old Herald building to see in Herald Square. The old building was crowned by a moving vignette of bronze statues sculpted by by Antonin Jean Carles: the Roman goddess Minerva and a bell struck on midday hours by two ringers who have, over the decades, acquired the names “Stuff” and Guff.” When the Herald building was razed in 1921, the vignette, after 19 years in storage, was placed, bells, Minerva, and ringers, in a large 40-foot tall granite stele after the 6th Avenue El had been razed (see below).

Minerva, the goddess of wisdom in the old Roman pagan beliefs, had a “spirit bird,” the owl, also perceived as a symbol of wisdom over the millennia. Bennett had several bronze owls displayed on the cornice of the Herald building along with Minerva and her bellringers, and two of the owls with outstretched wings appear on the stele. If you go by the monument at night, look for the owl’s eyes to blink green. There are a second pair of owls (one of which is shown here), with folded wings, at the Herald Square entrance north of West 34th.

It’s possible that the least-known corner Herald Square building is the Marbridge Building on the NE corner of Broadway and West 34th, which went up in 1909. For the last 15 years or so the ground floor tenant has been lingerie store Victoria’s Secret, but when I worked at Macy’s from 2000-2004 I could often be found there — when it was a branch of the British music retailer HMV, which had originated in 1921 and had branched out to NYC from its flagship on Oxford Street in London. The rise of MP3s and streaming put a severe dent in CD, cassette and LP retailing in the 2000s and 2010s. HMV went into receivership in 2018.

The sun is finally beginning to fade this painted ad for Weber & Heilbroner, which advertised on this exposed wall on the Marbridge Building facing West 35th Street at 6th Avenue. Frank Jump has the story of how he got a photo of the ad from a photo that has now been torn down. And, here’s a look inside some Weber and Heilbroner locations. The clothier was defunct by the mid-1970s.

This impressive marble-clad building with eight massive Corinthian columns marking the entrance, nine more Corinthian half-columns on West 36th and eight more on Broadway – not quite the spectacle of Colonnade Row on Lafayette Street in NoHo, but close — stands out on the somewhat drab stretch of 6th Avenue between Herald Square and Bryant Park.

The building was constructed as the Greenwich Savings Bank in 1924 [York & Sawyer, architects] as the seventh site of one of New York’s oldest banks, first organized in 1833 and operated until 1981.

The Haier Group, a European electrical appliance company, acquired the building as the headquarters of Haier America in 2002. The company maintains the former bank’s impressive brass entrance doors, oak-panelled executive offices and bronze tellers’ screens decorated with the figures of the Roman gods Minerva and Mercury, and rents the banking room, boardroom and offices for special events such as weddings and private parties. The exterior is illuminated in brilliant blue at night.

Another group of brick walkup buildings from a different era on 6th Avenue, between West 36th and 37th, that likely have a date with the wrecker’s before too long.

A milliner is a manufacturer and/or distributor of women’s hats, and the Garment District featured dozens if not hundreds of hat manufacturers in an era when men wore flat brimmed hats of various shapes and sizes, and women wore various hats of varying styles, one more outrageous than the next, in the early to mid-20th Century after which hats decreased in popularity beginning in the 1960s.

So many Jewish milliners and other clothing manufacturers worked in the area that the Millinery Center Synagoguewas established in 1933; the present synagogue by architect H.I. Feldman went up in a striking Moderne building at 1025 6th Avenue, just north of West 38th, in 1948.

When I passed Bryant Park in October 2023, preparations were already under way for the park’s Winter Village (for me, NYC “winter villages” are problematic as Arctic air doesn’t really incur into NYC in December as a rule any more) and ice skating rink.

I’ll pass here on getting into Bryant Park in depth, since I believe I wrote FNY’s definitive page on it in 2012.

Nikola Tesla (1856-1943) was a Serbian-born inventor, physicist, and mechanical engineer and is widely recognized as the greatest electrical engineer in history. He arrived in NYC in 1884, becoming a citizen in 1891. Tesla developed the basis of modern alternating current (AC) electric systems, pitting him in opposition with Thomas Edison, who championed direct current. Tesla experimented with X-rays and was an early radio pioneer. He founded the Nikola Tesla Company at 8 West 40th Street, on the south side of Bryant Park.

Tesla gained great fame but his last years were not happy ones. He had never married, nor paid much attention to his finances and died destitute at the New Yorker Hotel at 8th Avenue and 34th Street, where a memorial plaque was dedicated to him a few years ago. He loved feeding the pigeons in Bryant Park.

When Bryant Park’s renovations began in the 1980s, West 40th and 42nd Streets and 6th Avenue got a set of retro Twinlamp poles, including this one with a guywired stoplight attached, a combo never seen during the Twins’ original run beginning in the 1890s.

A geologist, poet, statesman and scholar, José Bonifacio de Andrada e Silva (1763-1828)was a leading contributor to the Brazilian Constitution of 1824. Brazil achieved its independence from Portugal–mostly peacefully–in 1822. Andrada became Brazil’s interior as well as foreign minister. He fell out of favor, however, the next year for opposing Brazilian emperor Don Pedro I’s policies and was exiled to France. Brazil’s constitution, featuring many of his ideas, was drawn up the following year.

José Lima’s sculpture of Andrada was presented to the USA as a gift by Brazil in 1954, the same year it took its place on The Avenue of The Americas. It was the winner of an open competition in Brazil.

Formerly at 6th Avenue and 42nd Street, Andrada’s statue, a 1954 work by José Otava Correia Lima, was moved to 6th Avenue and West 40th Street (Nikola Tesla Square) during Bryant Park’s 1990s renovations.

Five-term Mexican president Benito Juarez’s likeness is also in Bryant Park; 6th Avenue features numerous South American and Caribbean leaders along its length from Canal Street north to Central Park.

Speaking of lampposts, I have always been fascinated by these large bronze posts (made green with verdigris) unique to Bryant Park, paired up at the park’s entrances. It would probably take some digging to find out what year they appeared and who designed them. Ephemeral New York took note in 2013 but did not provide any history.

The Bank of America Tower, pretty much an immense glass wall as seen from the street, is in the top ten tallest buildings in the USA at 1,200 feet, but that will probably not last. It was opened in 2009 and took 5 years to build. The subway entrance outside the building received a glassy kiosk to complement it.

Before the Bank of America was built a low-rise building occupied the corner, with this City Walls mural by Alan Loving as a backdrop.

The Steinway family, master piano builders, transit magnates, and resort developers, put a personal stamp on the neighborhoods in which they resided that is visible even today. Henry Steinweg, a German piano manufacturer, immigrated to New York City from Seesen, Germany, in 1853. His sons Henry Jr. and Theodore set about making the finest pianos ever made, renowned the world over.

Henry Jr.’s and Theodore’s younger brother, William, continued the family tradition (advertising their instruments as “the standard piano of the world”) and moved the operations of Steinway Pianos to Astoria, Queens. Between 1870 and 1873, Steinway purchased 400 acres of land in northern Astoria and not only built the spacious Steinway piano factory, which still cuts an imposing figure, but a small town with a library, a church, a kindergarten, housing for factory workers, and a public trolley line. From 1877 and 1879, Steinway constructed a group of handsome row houses on Winthrop Avenue (today’s 20th Avenue) and on Albert and Theodore (41st and 42nd) Streets. Even the street names bore witness to the Steinway family, since Albert and Theodore were sons of Henry Steinway.

Meanwhile, here’s a Steinway Piano showroom at 6th Avenue and West 43rd. Obviously, Steinway doesn’t adhere to Henry Ford’s old rule, “You can have any color you like as long as it’s black.”

I think I may begin to pay more attention to lamppost designs on public plazas, like these specimens at #1155 6th Avenue at West 44th Street.

These luminaires have been illuminating sidewalks on 6th Avenue and side streets west of Radio City since the 1970s (though they have been relamped with LEDs). They are unique to the Radio City area.

Radio City Music Hall is the piece de resistance, along with Sunken Plaza, of Rockefeller Center, the great Midtown high rise urban project of the 1930s. When you frequent the Rock Center area, keep in mind that an 1880s-era elevated train rattled past as late as 1938.

When the theater first opened, it was the child of many fathers: the Rockefellers, RCA honcho David Sarnoff, and the Roxy Theater’s Samuel “Roxy” Rothafel. Originally it was conceived as a vehicle to bring “serious” entertainment back to NYC as a rebuff to honky-tonks, vaudeveille and burlesque. Opening night featured Ray Bolger and the Martha Graham dance company. The ‘high-class’ concept flopped and the next year, RCMH converted to the format that would serve it well for many years: a feature film combined with a stage show starring the leggy Rockettes, originallly known as the Roxyettes since they got their start at the Roxy. The Christmas Show, as well, has been a staple ever since the earliest days. The RCMH’s Wurlitzer organ was the largest ever built for a movie theater; the “Great Stage” ‘s elevators were so advanced that the US Navy copied its hydraulics while constructing aircraft carriers during World War II.

I have been within exactly twice: with my parents in spring of 1969 to see “The Love Bug”, you remember, the sentient Volkswagen, with Dean Jones and Michele Lee. I came back in 2008 to see its innermost secrets in an Open House NY tour.

The CBS Building at West 53rd, nicknamed Black Rock, was built by famed Finnish architect Eero Saarinen in 1965. It is really dark gray, not black. This is CBS’ legal and monetary headquarters: creative decisions are made elsewhere.

Buildings change names every few years. 1301 6th Avenue, at West 53rd, is currently called the Calyon Building, after the corporate and investment banking arm of the French Bank Credit Agricole (Credit Lyonnais)). Three sculptures by Jim Dine, under the collective name “Looking Toward The Avenue” and reminiscent of the Venus de Milo, grace the exterior plaza.

West 52nd Street is celebrated as the mid-20th Century center of jazz clubs in midtown Manhattan — it is subtitled both Swing Street and W.C. Handy‘s Place, after the so-called “father of the blues” (1873-1958). This was among NYC’s first “honorific” street names. Meanwhile, Cousin Brucie, honored in a now-rare blue street sign formerly used for honorifics, is NYC’s longest-serving disk jockey, heard on WABC, WNBC, WCBS-FM and radio streaming since the early 1960s. Now in his 80s, Bruce Morrow appears Saturday nights 6 PM-10 PM on WABC (as of December 2023).

The Warwick Hotel was constructed with funding by William Randolph Hearst in 1927 at 6th Avenue and West 54th Street. His mistress, Hollywood actress Marion Davies, had her own custom-accommodated floor in the building. Cary Grant lived at the Warwick for 12 years and it has hosted both Elvis Presley and the Beatles, when the latter played a block away at the Ed Sullivan Theater at Broadway and West 53rd in February 1964.

The Medical Arts Building, #57 West 57th at the NW corner of 6th Avenue, is an extraordinarily good-looking building, its Moderne outline embellished with Beaux Arts touches and plenty of gilding. It was designed by Warren & Wetmore for Alain E. White and had immediate occupation by doctors, dentists, psychologists and other medical professionals. Tom Miller describes some odd goings-on in the place.

The 57th Street IND station at 6th Avenue has served as the terminal for a number of subway lines. In December 2023, it was the northern terminus of the M train (6th Avenue/Bushwick/Middle Village) until trackwork is completed in 2024, whereupon the terminal will revert to Continental Avenue. In the late 2010s, the entrance was selected for an esthetic redesign and it resembles some stations in Brooklyn and Bronx which were given similar revamps.

José Martí (1853-1895), a journalist and political activist who worked for Cuba’s independence from Spain and freedom from domination by the US, is one of three Latin-American leaders honored along Central Park South. Marti founded the Cuban Revolutionary Party. Assisting in the Cuban revolution in 1895, he was mortally wounded and his statue, sculpted by Anna Huntington, depicts him at the moment of his death. “Guantanamera”, a popular folksong in the 1960s, was based on his poetry.

As always, “comment…as you see fit.” I earn a small payment when you click on any ad on the site. Take a look at the new JOBS link in the red toolbar at the top of the page on the desktop version, as I also get a small payment when you view a job via that link.

12/10/23