THIS is the second of a two-part post describing my walk from Washington Heights into The Bronx High Bridge neighborhood and then back to Harlem. The next day, I walked East Tremont Avenue from Westchester Square to Throg(g)s Neck. Only one walk was in full sun, and it wasn’t the one shown on this page. This spring has been the least sunniest in memory with gun metal gray skies and rain on 13 consecutive weekends. It is now mid-May and has been sunny on exactly three days. I do not prefer cloudy weather for my shoots because the colors are washed out and things look fairly lifeless. Since I work at home all week, until I take a vacation, the weekends have to be when I operate. In Part One, I crossed High Bridge and explored neighborhoods called High Bridge and Highbridge Heights, leaving off at Yankee Stadium.

(Lately the weather has improved somewhat — May 25)

GOOGLE MAP: WASHINGTON HEIGHTS – HIGH BRIDGE – HARLEM

The Macombs Dam Bridge connects Jerome Avenue at Yankee Stadium to West 155th Street, which is carried on a viaduct over Coogan’s Bluff to Edgecombe Avenue. It was repainted and renovated with new lighting about 20 years ago, but the pale yellow paint is now wearing off in several spots, leaving rust to poke through. It’s a movable span and can revolve to allow tall masted ships to pass, though I have never seen this feature in action. Pedestrians have the opportunity via a crosswalkn and stoplight to exit the bridge just west of Harlem River Drive rather than walk all the way to Edgecombe Avenue, but beware, pedal-to-the metal bridge traffic including trucks and buses is especially devilish there.

The Macombs Dam Bridge is the third bridge on today’s tour that was designed by Alfred Pancoast Boller. Like the 145th Street Bridge it offers no direct connection with the Harlem River Drive, which must be accessed via a ramp at West 155th Street and Edgecombe Avenue. Manhattan’s peculiar topography here, a high cliff known as Coogan’s Bluff, necessitates an elevated ramp that takes West 155th above Powell Boulevard and Bradhurst Avenue to an intersection with Edgecombe Avenue and the Harlem River Driveway at Maher Circle. This elevated roadway was alos designed by Boller and closely resembles his other bridges in the area.

The bridge is named for a dam and bridge built by Alexander Macomb, who ran a grist mill in the area in the early 19th Century. He constructed a dam and bridge across the Harlem River that was finsihed by 1814, with a toll charged for passage: it became controversial in later years as the toll was forcibly disputed. The original Macomb’s Dam was demolished and a new drawbridge built in 1858, known as the Central Bridge because of its central location on the Harlem River. Macomb is remembered by the bridge, Macombs Place in Hamilton Heights and by Macombs Road in Morris Heights, Bronx.

The second bridge was deemed as irreparable by 1890, and yet another bridge was planned. The 412-foot Macomb’s Dam Bridge, also known by the previous title Central Bridge, opened in 1895. It is the most architecturally ornamented of the Boller Harlem River spans. On NYCRoads, Steve Anderson quotes bridge historian Sharon Reier:

The bridge has been humorously likened to a raffish tiara. Following the precedent of the currently novel Tower Bridge in London, which had used Tudor-style architecture in its abutments, Boller had designed Gothic-revival structures to abut the Macombs swing span. This choice of architectural style makes some sense, as drawbridges did originate with the moats surrounding medieval castles. It is the only movable bridge over the Harlem that warrants a walking tour. The others, also completed around the turn of the century, are less interesting, or are downright blights on the river.

The Colonel Charles Young Triangle, wedged between Macombs Place, the pedestrian West 153rd and Powell Boulevard, gave me a chance to sit and rest for 10 minutes (at 66, resting midway through a walk is becoming more necessary). The triangle’s namesake, Col. Young (1864-1922) had a colorful military career that is Hollywood-worthy. He was just the 9th African American graduate of West Point in 1884 and commanded the 9th Ohio Volunteer Infantry on the home front during the Spanish-American War in 1898, and later served during a Philippine insurrection between 1901 and 1903. Trained as a cartographer, Col. Young made military maps and in 1912 published a book, Military Morale of Nations and Races.

He was later feted by the NAACP for his contributions in organizing Liberia’s National Military Constabulary from 1912 to 1915. The next year he led the 10th Cavalry Regiment against incursions in the American southwest by Mexico’s Pancho Villa and established a school for African-American soldiers at Fort Huachuca, Arizona. He was pronounced physically unfit for service in World War I, but was promoted to full Colonel at the war’s outset. He passed in Lagos, Nigeria in 1922 and was laid to rest in Arlington National Cemetery. This park was named for him in 1937.

Before the 1990s, this park featured a flock of now-rare Type F lampposts, but they were torn down when the park was renovated in 1997. However; all isn’t lost for fans of ancient lampposts here.

Adam Clayton Powell Boulevard (7th Avenue) is shunted to the Harlem River Driveway via a ramp under West 153rd Street. For decades the ramp, on which traffic was light, was illuminated by a set of ancient, rusted iron posts with a unique design, employing SLECO 1950s-era “cuplights.” In the early 2000s the posts were granted a paint job (especially rusty ones were removed and replaced by Triborough-style poles) and the cuplights were replaced with post-tops.

7th Avenue above Central Park was renamed in 1974 for Adam Clayton Powell Jr., the flamboyant and charismatic politician (1908-1972) who served 11 terms in the House of Representatives; in 1945 he became the first African-American from NYS elected to the House) and was the first black member of the City Council. After losing his seat and winning it back, Powell chose to retire to the island of Bimini, where he died in 1972.

During his congressional service, Powell served on a number of committees and continued to agitate for African-American human rights, calling for an end to lynching in the South and Jim Crow laws. He angered Southern segregationists, including those within his own party, by integrating congressional restaurants, recreational facilities and press stations; critiquing anti-Semitism; and advocating for independence for African and Asian nations. In 1956, Powell went against party lines to support Republican Dwight D. Eisenhower‘s presidential campaign, though he later critiqued Eisenhower for his conservatism on civil rights issues.

In 1961, Powell became chair of the House Committee on Education and Labor. The special group was able to create an unprecedented array of legislative reforms, including a minimum-wage increase, educational resources for the deaf, funding for student loans, library aid, work-hour regulations and job training. Biography

It occurred to me that I had never walked ACP Boulevard along this stretch, though I had visited it, so I continued downtown.

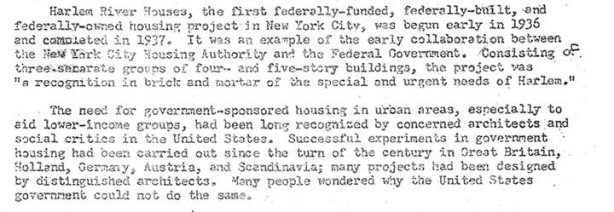

When you walk south on ACP Blvd. from the Macombs Dam Bridge, you’re met right away by a landmark, the Harlem River Houses, which is plain brick architecture that I like and built in the same era as my place, Westmoreland Gardens, and were designed by Archibald Manning Brown. The Houses were deemed worthy of landmarking fairly early on in 1975. Here is a clip from the Landmarks Preservation report:

Harlem luminaries such as A. Philip Randolph, Paul Robeson and Bill “Bojangles” Robinson lived here in the past.

Crossing West 145th Street I spotted a figure across the street at a Fine Fare supermarket and thought, “I know that guy” — it turned out to be Teddy Roosevelt. The building likely went up during his years in the White House between 1901 and 1909. Roosevelt Avenue in western Queens is also named for him.

[This was apparently a theater: see Comments]

On streets west of ACP Blvd. I encountered a pair of historic districts with handsome attached brick apartments. The St. Nicholas Historic District, despite is name, ic not located on that avenue, but from West 138th-140th Streets between ACP Blvd. and Frederick Douglass Boulevard (8th Avenue). The St. Nicholas district was conceived by developer David H. King in 1891 and built by three architects, James Brown Lord, Bruce Price and Stanford White. When African Americans purchased and moved into the buildings in the 1920 the blocks became known as “Strivers’ Row.” Famed musicians Eubie Blake, Fletcher Henderson and W. C. Handy lived in the district, along with architect Vertner Tandy and boxer Harry Willis.

The modern apartment building at ACP Blvd. and West 138th Street replaced a major mecca of Harlem nightlife in the 1930s in its incarnation as the Renaissance Ballroom. The “Renny” offered dancing, cabaret acts and the finest bands of the era, including those of Vernon Andrade, Fletcher Henderson and Chick Webb. Its builders were William Roach and James Sweeney, from Antigua and Montserrat in the Caribbean Sea.

The adjoining Renaissance Casino was the home court of the 1920s Harlem Rennies or Rens, the first all-Black professional basketball team, which racked up a 2588-592 record against other local competition in the pre-NBA era.

The Rangely Apartments, and its impressive entrance portico, were built in 1897 and designed by architect Harry Anderson.

Between West 135th and 138th Street ACP Blvd. encounters the east end of the Dorrance Brooks Square Historic District, a new Landmarked district designated in 2021 in two pieces, one roughly between Powell and Douglas Boulevards and the other between Doulass Boulevard and St. Nicholas Avenue between West 136th and 140th.

The Dorrance Brooks Square Historic District consists of intact streetscapes of a striking variety of 19th and early-20th century row houses, multi-family dwellings, and institutions, designed by prominent New York City architects within two sections on either side of Frederick Douglass Boulevard between West 136th Street and West 140th Street. Anchored by Dorrance Brooks Square, named after an African American war hero whose actions helped to dismantle racist notions about Black Americans in military service, it has rich associations with the Harlem Renaissance and Civil Rights movements.

Among the prominent residents associated with the Harlem Renaissance were the intellectual and essayist W. E. B. Du Bois, stage and motion picture actress Ethel Waters, and celebrated sculptor Augusta Savage. Savage and other artists also had studios in the neighborhood, such as the Harlem Artist Guild and the Uptown Art Laboratory. In their home at 580 St. Nicholas Avenue, Regina Anderson, Luella Tucker and Ethel Ray Nance, fostered the careers of notable Harlem Renaissance artists Countee Cullen, Langston Hughes and many others by hosting “the Harlem West Side Literary Salon,” known simply as “580” to those who attended. Historian Charles Seifert founded the Ethiopian School of Research History on West 137th Street in 1920s, a collection of African art and artifacts and rare historical which later became the Charles C. Seifert Library.

Additional info: Dorrance Brooks Property Owners and Residents Association

The Hotel Fane, now a women’s shelter on West 135th Street between ACP Blvd and Douglass Blvd., is among a handful of businesses remaining that were listed in the Green Book, a directory of businesses, restaurants and hotels that were welcoming to African Americans in segregated America published from 1936 to 1966. The directory was devised by mail carrier Victor Green, whose Green Book offices were located further east on West 135th Street.

West 135th is a bit unusual: there is perpendicular parking on the north side, lilkely because of the midblock police precinct, and both sides of the street have exposed Belgian blocks (probably a product of recent renovations). The sidewalk features a Harlem walk of fame with numerous diamond-shaped plaques featuring area luminaries.

In honor of his centennial, a giant mural of great jazz trumpeter John Birks “Dizzy” Gillespie (1917-1993) was painted by Brandon Odums and Marthalicia Matarrita for the organization Education Is Not a Crime in 2017, on a wall surface facing an NYPD parking lot.

Ready for a rest after about 4-5 hours, I wound up pretty much as I started, at an IND subway, this one for the C local at 135th. This station is notable for being the only NYC subway station with a six-track spread instead of the usual two or four.

Kevin Walsh is the webmaster of the award-winning website Forgotten NY, and the author of the books Forgotten New York (HarperCollins, 2006) and also, with the Greater Astoria Historical Society, Forgotten Queens (Arcadia, 2013)

5/26/24

9 comments

I so enjoy and appreciate your detailed documenting of the City’s history … and I love the book!! Thank you.

An interesting stop in Harlem is the 369th Inf. Regiment Armory-home of the Harlem Hellfighters.

I scrathced the surface, will return soon

The building with Teddy Roosevelt on it was a movie theater.

The building with Teddy Roosevelt on it was a movie theater. Opened in 1920. Fats Waller won an amateur contest. RKO took over in !937, but it converted back to an African-American movie theater in the 1940’s and it closed in 1978.

You can look it up on Cinematic Treasures.

This is fabulous, Kevin! I miss going on Forgotten NY walks.

Fascinating and very informative. Thank you for sharing this.

I always thought with a name like that for a bridge there probably had to be a dam there at one point, otherwise that name would just sound random.