FOLLOWING my revisit of upper 5th Avenue in Park Slope in early 2024 I decided to stalk south on 19th Street into the heart of Windsor Terrace, as I had never been on parts of that particular street. I think I’ve “undercovered” Windsor Tterrace over the years (in fact Forgotten New York the Book overlooks it!). If you look for it on a Brooklyn map, it occupies an odd wedge of territory between two vast, yet quite different areas of green: Green-Wood Cemetery and Prospect Park, each among my favorite areas in Brooklyn to walk around in. I wound up walking 19th Street along the Prospect Expressway before tiring and heading into the Ft. Hamilton Parkway F train.

The neighborhood, named for Windsor, England, was first built up by developer William Bell between 1849 and 1851 between Vanderbilt Street and Greenwood Avenue, and row houses sprang up on 16th Street and Prospect Park Southwest by 1905. Windsor Terrace was heavily Irish in the early 20th Century, and remains a quiet, relatively undiscovered neighborhood despite the construction of the Prospect Expressway from 1953-60; thankfully, a proposal to extend the expressway south along Ocean Parkway — which would have become a 6-lane expressway–was never acted upon.

In case you missed it, I’ll reprise my comments on the impressive Hutwelker Building at the corner of 5th Avenue and 19th Street, which still retains its name on the pediment, as well as its flagpole. Here’s what the corner looked like in 1940. As you can see, the 5th Avenue El was shrouding the avenue in its final year of service, as it had done since it was extended past 19th Street in 1889. At the time, spotting that “Hutwelker Building” sign on the pediment would have been tough… unless you could do it from a station platform. As it happened, the el had a stop at 20th Street, so that may have been the case.

Frederick Hutwelker operated a pork packing enterprise with his two brothers beginning in 1896 (the business was physically located on the Hudson River waterfront in the West 40s in Hell’s Kitchen, which had its own stockyards district in the late 19th-early 20th Century).

Though I am not religious, I enjoy finding small midblock churches, such as the St. Nicholas Ukrainian Catholic Church on 19th Street between 5th and 6th Avenues. I cannot find much information but the parish was established in 1911 and the church built in the 1920s. It has three small modest onion domes typical of Eastern Catholic churches.

I liked the treatment on the relatively new #288 19th Street, which replaced this frame house seen here in the 1940s. On the left, #290 has kept some of its old detail (unlike most buildings on the block) but is in need of major exterior repair.

These attached 3-story brick walkups on the south side of 19th between 6th and 7th Avenues looks much the same as they always have for most of their-century-old existence. Even most of the decorative pediment treatments have been kept; these are usually removed when the begin to come loose and owners remove them instead of seeking out similar replacements, which would be expensive.

At least in the city, you don’t see a lot of car washes that have an outdoor sitting area where you can have lunch, but there’s enough space here at 19th Street and 7th Avenue to allow it. Which gives me an idea. How bout a combined car wash/restaurant franchise? Light meals while your car is scrubbed? Call me.

The east side of 7th Avenue between 19th and 20th Street was formerly occupied by a car barn operated by Brooklyn Rapid Transit (BRT) to service its streetcars.

This shot of the Prospect Expressway is obtainable at 7th and 19th. Traffic czar Robert Moses constructed the roadway through the north-south Windsor Terrace axis from 1953-1962 to connect the Brooklyn Battery Tunnel to Ocean Parkway, and wished to extend it further south along Ocean Parkway to Coney Island and perhaps even further to the Marine Parkway Bridge via Flatbush Avenue, but fortunately those projects lost steam in the 1970s, and Ocean Parkway remains a pedal to the metal roadway, but with parkland on both sides.

Like most of Moses’ city projects, middle class and poor people had to be moved out of the way, and houses and factories along 18th and 19th Streets were demolished to accommodate the Prospect.

Prospect Park flowing traffic into a local access road is unusual in NYC. The feat was repeated in Queens in 1962, with the Clearview Expressway’s abrupt southern end at Hillside Avenue.

I had thought this lengthy peak-roofed brick building at 8th Avenue and 19th Street had been a trolley car barn. Instead, it’s the former Cohen Brothers Furniture Warehouse. Today, it’s a Jewish girls’ high school, Mesilas Bais Yaakov.

A pair of unusual cylindrical pedestrian crossings span the Prospect Expressway at 8th and 10th Avenues. They seem to be unique designs in NYC. When the expressway was built, two one-block sections of 8th and 10th Avenues between 19th and 20th Streets were “orphaned” from the roads’ main sections.

Despite the loss of nearby Bishop Ford High School (see below), the Catholic Church remains a prominent presence in Windsor Terrace, with the Brooklyn Diocese offices located in this large headquarters at #310 Prospect Park West (despite the front door on 19th Street).

I had been unaware that the former Bishop Ford High School, on 19th Street between 10th Avenue and Prospect Park West on the Park Slope-Windsor Terrace border, boasted a distinctive Asian cast in its architecture and signage, but there was a reason for that.

Born in Brooklyn, New York, in 1892 [Francis Xavier] Ford became the first student to apply to the seminary of the recently established Catholic Foreign Mission Society, also known as Maryknoll. Ordained in 1918, he was one of the first four Maryknoll missioners to leave for China. In 1925 he was appointed head of the newly created mission territory of Kaying, or Meihsien (Meizhou), in the northeastern corner of Kwangtung (Guangdong) Province…. In December 1950 he was arrested by the Communists for alleged spying activities. Four months later, he was pronounced guilty and sentenced to the provincial prison in Canton. He died in jail of exhaustion and illness in February 1952. [BDCC Online]

The Chinese mission of Francis X. Ford is strikingly reflected in the design of the school. The cross which surmounts the pagoda on the roof is a landmark visible for miles. Red and black, the colors symbolic of the Chinese artistic tradition and the Maryknoll Fathers, permeate the school. These colors in the chapel, the main lobby, the auditorium, throughout the classrooms, are constant reminders of Bishop Ford and his contributions and good works. [Bishop Ford High School]

Even the lamps by the entrance have an Asian motif, with pagoda-like ornamentation.

Now known as the MS 442, Brooklyn Urban Garden Charter School, and PS 281, the building was constructed in 1962 on the site of BRT car barns. Falling enrollment prompted the Brooklyn Diocese to close the Catholic boys’ high school in 2014.

When the Prospect Expressway was built in the late 1950s, there was some leftover spaces along the right of way and in many cases, these have been turned into parks. This one, across 19th Street from the former Bishop Ford, was oddly naver given a name even by quirky Parks boss Henry Stern in the 1990s, and is still signed merely “Park.” Its original 1950s moldings and railings have to be considered vintage.

When I am out walking I make mental or photographic notes of diners or coffee shops where I can refuel. One is the Terrace Coffee Shop, 19th Street and Terrace Place, where 11th Avenue is bridged across the Prospect Expressway.

Some of NYC’s narrowest parks can be found on either side of the Prospect Expressway, which runs in an open cut through Windsor Terrace, that narrow strip of territory between Green-Wood Cemetery and Prospect Park in Brooklyn. One of these is Thomas Cuite Park at 11th Avenue, pronounced “cute.”

How do I remember the pronunciation? Cuite (1913-1987), a veteran politician, was a big deal in Brooklyn in the 1960s and 1970s and his name was often on the evening newscasts. a Saint Francis College alumnus (like me), he served in WWII and subsequently entered politics, in the NY State Senate from 1953-1958. A Democrat, he served in the NY City Council between 1969 and 1985, succeeded by Peter Vallone, Senior. He was a conservative Democrat allied with the Catholic Church and worked closely with Cardinals Spellman, Cooke and O’Connor. He passed away in 1987 after suffering a heart attack.

Seeley Street is among the handful of streets that run only through Windsor Terrace and no other neighborhood, though as mentioned, the neighborhood is wedged between Green-Wood Cemetery and Prospect Park. Historians seem stumped as to the name’s origin, as Parks can’t pin it down and Benardo/Weiss don’t cover it in Brooklyn By Name.

Seeley Street runs over two overpasses: a bridge across the Prospect Expressway, and over Prospect Avenue, which is in a valley when it encounters the street.

Seeley Playground is another of the Prospect Park’s “pocket parks” between Seeley and Vanderbilt Streets.

Shown here is the intersection of Vanderbilt Street and East 5th Street. Vanderbilt Street runs from McDonald Avenue at Green-Wood Cemetery east to Prospect Park Southwest but since the 1950s has been cut into two parts by Prospect Expressway. You’d be excused for thinking that it was named for Vanderbilt Avenue, named for Cornelius Vanderbilt, the original ferry operator between Manhattan and Staten Island and later, a steamship and railroad magnate (and great-great-great grandfather of TV newsman Anderson Cooper). However, in Brooklyn By Name, Leonard Benardo and Jennifer Weiss say it was named instead for the progenitor of the Vanderbilt family in America, Jan Aertsen Vanderbilt, who settled in Flatbush when he arrived in the New Netherland area in the 1650s. The name means simply “from the town of Bilt, (Netherlands.)

If you look at a Brooklyn map, you can see why I consider Vanderbilt Street important as far as Brooklyn street girds go, since like Dahill Road further south, it’s the dividing line between two street numbering systems: the simple numbered system employed by the City of Brooklyn (which begins in Park Slope and ends in Bay Ridge/Bath Beach, with 1st through 101st Streets and 1st through 28th Avenues, and the Flatbush town numbering system, with two sets of numbered streets, East and West (which actually run north to south and are divided to be east and west of McDonald Avenue); cross streets are lettered, Avenue A to Z. Brooklyn has sets of North, South, East and west numbered streets, which has been repeated in other cities countrywide but not quite the same way as Brooklyn.

{see comments for another possible origin for the street name]

Another of the Expressway’s “pocket parks” is found at Vanderbilt and East 5th Streets, Captain John McKenna IV Park, named for a local soldier killed during Operation Iraqi Freedom. The park may have gone unnamed like the one shown above prior to the current name bestowed in 2006. The park has three different signage methods, including the red frame which seems to be used only in Windsor Terrace at present.

Here, East 5th Street takes over as the Prospect Expressway’s west “service road.”

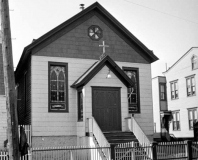

Just north of McKenna Park is the nondenominational Boro Church, established by local residents in 2019. The building, described only as “Lutheran Church” on a 1929 atlas, has had much of its ornamentation stripped off since it was photographed in 1940.

Then, out of nowhere, comes a row of Victorian-style jewel box houses and cottages on East 5th, any of which I’d gladly live in based on the exteriors alone. At one time you would see similar buildings out the front window, until the expressway was built in the 1950s. These buildings have probably been altered too much over the years to rate Landmarks Preservation Commission note, but I notice them every time I am here.

At Greenwood Avenue there is a handy pedestrian (and bicycle) bridge spanning the expressway. From the 1890s through the mid-1950s this was the location of the formidable-looking Windsor Terrace Methodist Church.

Just as formidable is sculptor Charles Keck’s bronze memorial to Windsor Terrace WWI casualties next to the bridge. It was originally located at Fort Hamilton and Ocean Parkways, but no doubt expressway construction caused its move to this location.

Any botanists reading this? I have an idea. Breed cherry trees so the blossoms stay on the tree all summer. You have to get to cherry trees in a two-week window in March and April to see them in full glory.

The Fort Hamilton Parkway F/G train station is hidden on a ramp at the south end of Prospect Expressway’s last “pocket park,” Greenwood Playground.

As always, “comment…as you see fit.” I earn a small payment when you click on any ad on the site. Take a look at the new JOBS link in the red toolbar at the top of the page on the desktop version, as I also get a small payment when you view a job via that link.

10/6/24

9 comments

Wow, two of my family homes made the post.

#50 and #52 East 5th St. ( The cottage and the blue house next door)..

These are still occupied by family. The cottage was built ca. 1860 based on records we’ve found over the years. We also found an d piece of paper behind a base board in a closet years ago. It said in part , that the owners of the “cottage” had permission to use the well near the cemetery on Mr. Murphy’s land, wherever that was.

The little church on East 5th St, according to IHM church records was the original meeting place of parishioners of IHM before they bought the land on Ft. Hamilton.

Don’t know if any of the first part of my comments

were received before I accidentally sent it off, but

here’s the rest of it.

I grew up in Windsor Terrace in the 1940’s and 1950’s.

Some of this is my first recollection. Other of it was

from my maternal grandmother, Louise (a) Judge, of German descent (Grossman) whose family emigrated from Bavaria, a largely Catholic region.

The house in which I was raised, 215 Vanderbilt

Street, between East 2nd and East 3rd Streets,

was one of the first homes in the neighborhood

[1880]. It was built on Murphys farm, most likely

on hilly pasture land at one time.

Sadly, Windsor Terrace was cut in half for the

Prospect Expressway. So, here’s the collective

memory of the Judge family. Although Prospect

Avenue [formerly Main Street] represented a modest

shopping district, running from Vanderbilt Street to

Greenwood Avenue. Besides an A & P, there was a

cleaners, two bars, one or two drug stores, a dry

goods store, a “candy store,” a funeral home, dentist,a movie theater, the Venus, and the Ft. Hamilton

station of the subway. There were no stores between Prospect Avenue and Prospect Park.

Running east, along Vanderbilt Street, beginning at

East 2nd Street, were two bars, a grocery store, a

delicatessen, a drug store, a butcher shop, two candy stores, a fish store, a fruit and vegetable market,

and a store front which served as a meeting place for the Hiberians. On East 3rd, just below Vanderbilt

Street, was another store front which served as

political club, and a meeting place for the Windsor

Terrace Royals, a little league team which played at

the Parade Grounds. Lastly, so I’ve been told, was a

large lot at the corner of East 3rd and Greenwood

Avenue which was the place of a traveling circus

which set up its tents every summer.

Oh, incidentally, isn’t Bishop Ford High School the

former location of the old trolley barn.

Yes, Prospect Avenue was “Main Street, USA”. Some things, like The Venus were before my time, but my mom spoke of it. I believe it became an American Legion Hall. I remember the A & P, Bohack’s “up the hill”, there was Garfinkel’s Luncheonette, Mr. Quartana had the drugstore on the corner of Reeve Place (there was another drugstore at the corner of Greenwood), Mr. Von Seggern had the delicatessen, there was a butcher shop with sawdust on the floor, I think the dry goods store may have been Selinger’s, H. G. Yick’s Hand Laundry, E. F. Higgins was the undertaker. Many of these businesses were converted to ground floor apartments circa the early 70s.

No stores between Prospect Avenue and the park on Terrace, Seeley, Vanderbilt or Greenwood; on Reeve there was Baldo’s (grocery) at the corner of Sherman Street, and earlier Fleck’s Bakery (before my time, torn down) between Sherman and the park.

Whenever I walked through Windsor Terrace I had trouble finding my way back out and wondered if it was like Brigadoon, frozen in time and sometimes disappearing and reappearing.Sometimes Seely St is there, and sometimes it ain’t. This neighborhood appears to have been cut into a big hill with multiple levels, and at least one street that seems to tunnel under the others, so what is the deal? Is the area a natural formation or was it built by some real estate developer who cut actual terraces into a hillside to build houses for sale on various levels with streets at different levels fronting them? I think it is built into a high point of the Terminal Moraine that runs from Bay Ridge (it is the ridge!) east to Bushwick, just about the whole west to east cross dimension of Brooklyn. I think there are three spots in the area where you can see to Manhattan one way and then turn back and see to Coney Island. One is in Greenwood, one is in Prospect Park and I think the third is in Windsor Terrace. And there is a spot in Ocean Hill where you can see Manhattan one way and turn to see Jamaica Bay.

Who dreams up these pretentious names – Brooklyn Urban Garden Charter School? No self-respecting kid growing up in Brooklyn in the 50’s-60’s would have been caught dead wearing a school jacket with “Brooklyn Urban Garden Charter School” on the back. On the other hand, New Utrecht High School jackets sold for a premium…

Except that most people call it “BUGS” – not too pretentious! Also, sadly, I doubt there are any school jackets being minted these days.

A note on some Windsor Terrace streets:

Terrace Place roughly follows the old boundary between the City of Brooklyn and Flatbush Township.

Seel(e)y Street: I too have researched this and have come up emptyhanded. It’s like Beverl(e)y Road, in that the “e” comes and goes. Seeley Street was bridged over Prospect Avenue circa 1903, when the city decided to cut through the steep hillside and connect two sections of Prospect Avenue, creating a straight run from the Hamilton Avenue Ferry through to Coney Island via Ocean Parkway.

Vanderbilt Street: Henry R. Stiles’ 1884 “History of Kings County and the City of Brooklyn” states that Windsor Terrace “was originally the farm of John Vanderbilt, divided at his death between his two sons, John and Jeremiah. The dividing line of these two farms, which were purchased by Robert Bell, is Vanderbilt Street.”

Reeve Place: Originally Adams Street; when Flatbush Twsp. was annexed by the City of Brooklyn the Council changed many duplicated street names. Appears to be named for James F. Reeve (1863-1896), charter member of Windsor Hose Co., No. 3, having served as the company’s Foreman (Captain) and Secretary. The all-volunteer Windsor Hose was absorbed into the Brooklyn Fire Dept. (BFD), and ultimately evolved into today’s Engine 240.

Greenwood Avenue: Obviously named for the nearby Green-Wood Cemetery. BUT another possibility could be that it was named after Judge John Greenwood, a prominent attorney who studied under Aaron Burr. Judge Greenwood was the first City Judge after Brooklyn was granted city status, and later served as Corporation Counsel and in 1843 was appointed to the Kings County Court of Common Pleas. Under this theory the Kings County Town Survey Commission, which between 1869 and 1874 laid out the streets in the Town of Flatbush, may have opted to place a street named after Judge Greenwood near Green Wood Cemetery.

Windsor Terrace is not only where the Brooklyn city street grid and the Flatbush street grid meet, it’s where three grids actually overlap. The third grid is the original 1850s plan of Windsor Terrace, which followed the direction of farm properties and parallels the street grids of Parkville and part of South Greenfield.

Were it not for the IND South Brooklyn Line subway, Greenwood Avenue may have been bridged over the Prospect Expressway. Much of the expressway runs in a depressed cut. Because of the location of the subway the expressway had to be built at grade level in the FHP-Greenwood Avenue area before dipping down again to cross under Caton Avenue.

I forgot to mention that it’s worth a visit to the

Brooklyn Public Library at Grand Army Plaza.

It contains a “Brooklyn Room ” which has a table size book which has various street grids of many (all?)

neighborhoods as of 1890 in gorgeous colors, which puts one in mind of ancient bibles illustrated by

monks. There is a page for Windsor Terrace which

shows every street which existed at the time,

including Vanderbilt Street and Main Street.

While you’re at the library, you might want to ask to

see a section of the hull of the HMS Jersey, the

notorious British prison ship which, was anchored

where the Brooklyn Navy Yard would eventually be

built.

ncluding

I love Windsor Terrace’s mysterious “tucked-away” quality. And even though I grew up in B’klyn and visited Prospect Park many times, I never even knew it existed until my daughter moved nearby.