As some know, I have “found a home” (as much as I find any workplace “home”) at biographical publisher Marquis Who’s Who, where I format and edit biographies, working at home here in Little Neck, both on salary and pay per piece (I work 7 days a week). You may also know that I wandered in the wilderness for 10 years, 2011-2021, taking work where I found it. My journeys took me to companies big and small that included Tiffany & Co. and Pearson Publishing, where I had lengthy stints. On one of those varied gigs I found myself at a financial publisher, Summit Financial, that by chance happened to be in the very same building, 216 East 45th, where my typographical career started, at the city’s biggest type shop, Photo-Lettering, where I worked from 1982-1988. The type and editing biz is a transitory one and I have never stayed at the same company for more than 7+ years.

Anyway, the Summit gig was a pure overnight shift, from midnight to eight. I had never before done a true third shift, though at Photo Lettering I was second shift, arriving at 5 PM- 7 PM and with no overtime, leaving at 3 AM or 5 AM. Often, though, there were print jobs on tight deadlines and there was plenty of overtime to be had; one Saturday I was finally finished… at 1 PM. I was young and had plenty of stamina.

Unlike my friend Mitch Waxman and his collection of professional cameras he employs for the Newtown Pentacle both day and night, my Lumix has never been suitable for night shots as everything in insufficient light turns out blurry. My IPhone, though, is adept in low light, as long as the zoom is not overused. With that in mind I did some photography both en route to work and going home at night and in low light. These shots have leaked out in dribs and drabs the past 6 years, but I thought I’d just collect them on one page. Now at age 67, I don’t think I’ll take any more overnight jobs, as I didn’t sleep well at all during the day during my two months at Summit.

I will post the photos in chronological order without a theme. Hope they are of interest.

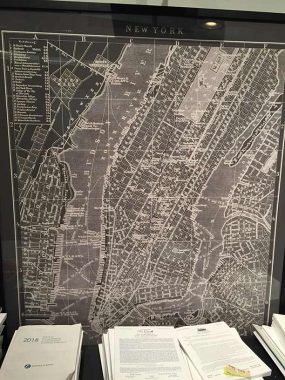

I did not take a lot of shots of the Summit office itself though things were interesting, with a large aquarium and several rooms with plush chairs where the daytime big shots sat. I found this 1890-1900 reproduction of a German map pf Manhattan interesting. You can’t tell from here but the streets were shown in their English spellings but notations for hotels, hospitals, etc. were in German. I wish I could link to something zoomable, but I don’t know the publisher (do you know? Comments are open). You can see sample documents I had to check at the bottom. Financial publishing is the most slumber-inducing material to copy edit and I had to fight off sleep at the very time I should have been sleeping.

I found this item by my desk a convenient place to put my hat.

The same view around 7 AM by dawn’s early light.

Here’s what the big clock at Grand Central Terminal looks like at 11:40 PM. I was happy to walk through this room every day from 1982-1988 and again for a few weeks in 2018.

Vincent Scully (the architecture scholar, not the longtime Dodgers broadcaster) said of Penn Station, “One entered the city like a god. Perhaps it was really too much. One scuttles in now like a rat.” Other than the rats on the nearby Graybar Building awning, there aren’t a lot of rats immediately apparent here, but undoubtedly there are rats in the enormous basement. Grand Central Terminal (railroad buffs get incensed if you say “Station”) has held forth here for over a century. It has occasionally been bowed, but never really broken. After its restoration in the 1990s, it has become a lunchtime attraction for people who never take a train issuing from the station.

Grand Central Terminal once served both The New York Central and New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroads, reaching a large swath of the country. Today, in a somewhat ironic turn of events, Grand Central Terminal serves only commuter railroads while the much more downscale (since 1964) Pennsylvania Station serves nationwide routes. The terminal was in danger of demolition in the 1970s before a group of preservationists led by Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis helped save it. After a lengthy period of neglect, it has been undergoing renovations since then, first the interior in the 1990s, and the exterior in the mid-2000s.

In April, this is what #622 3rd Avenue at East 40th Street looks like at 8:34 AM.

3rd Avenue and East 36th, 8:15 AM. The building on the left was demolished in 2023.

Occasionally I would walk back to Penn Station for the LIRR instead of getting the #7 at Grand Central. Here, I made sure to pass Sniffen Court. Nestled in prosperous Murray Hill on East 36th Street between 3rd and Lexington is one of the few alleys of the midtown area. Sniffen Court was constructed between 1850 and 1860 and consists of ten handsome brick carriage houses protected behind a locked iron gate. The carriage houses were built by architect John Sniffen and were originally used as stables until the 1920s, when they were converted into living spaces.

The rear wall features plaques of horsemen created by artist Malvina Hoffman, who lived in Sniffen Court for over forty years. The album cover of the Doors’ Strange Days in 1967 features the alley. Sniffen Court was formerly the home of The Sniffen Court Dramatic Society, an amateur theater group that performed plays in a theater located in the court.

I’m reminded of some photos of Sniffen Court taken by Andrew Cusack, which are no longer online, but his website is, and he’s an infrastructure guy as I am.

I have not yet done a FNY Crosstown series on 31st Street, which I’ll have to see about. On this day en route to Penn Station I found this building, Hotel 31, at #120 East 31st, constructed as The Dunsbro apartment house by Charles Grimmer in 1902. Tom Miller, the Daytonian in Manhattan, has the story:

Completed in 1902 at a cost of $90,000 (nearly $2.7 million today), The Dunsbro was a reserved take on the Beaux Arts style that often appeared in hotels and apartments with overblown decorations like festoons, wreaths and cartouches. The two-story stone base had none of these, the architects focusing instead on a stately portico with paired polished granite columns that supported a balcony and announced the building’s name. Four stories of beige brick included angled metal bays. The seventh floor echoed the rusticated stone base and its paired openings were fronted by handsome iron railings. Above the bracketed cornice a copper clad mansard featured prominent dormers.

Also refer the article for Grimmer’s later troubles, and some interior shots.

I was attracted to Railway Station Cafe, #119 West 31st between 6th and 7th Avenues, as it employed subway sign “bullets” in the sign design. Of course, all the fonts and colors are wrong.

I’ve never heard, “meet me at Pershing Square.” As a rule when I’m meeting up with people in this part of town, we usually meet at the iconic clock in the center of the vast marble floor at the center of Grand Central Terminal. Nonetheless the section of E. 42nd St. that’s overshadowed by the Park Ave. Viaduct, and formerly intersected by Park Ave. itself is officially known as Pershing Square, the name emblazoned on the iron bridge that crosses E. 42nd.

General John Joseph Pershing (1860-1948) was the leader of the American Expeditionary Force in Europe when America entered WWI in 1917. Previously he’d served in the so-called Indian Wars, fighting the Apache and the Sioux from 1886-1890; the Spanish-American War in Cuba in 1898 and later in the Philippines in 1903 after which President Roosevelt elevated him to brigadier general; he fought revolutionary Pancho Villa when he raided the American Southwest in 1916; and the Germans in WWI. It can perhaps be said that he led troops on more continents and against a greater array of opponents than any other previous American commander.

When the Park Ave. Viaduct was constructed in 1919, the name of the still-relatively young Pershing was bestowed on its crossing over E. 42nd St.

About a decade ago as of 2024, GCT decided to restore some of the original post-top lamps that were installed on the wraparound traffic ramps connecting Park Avenue north and south of the building.

I discovered this illuminated subway sign quite serendipitously when wandering around the Grand Central Terminal area prior to checking into Summit for the night. It’s just inside the cavernous entrance to Cipriani on East 42nd just east of Park Avenue and consists of gilded wrought metal. The MTA has vouchsafed its preservation, and could just as well removed it and installed a standard sign, so I’m glad they decided to make an exception to the rule here. Also check out that gorgeous lamp sconce next to it.

The 1921 Italian Romanesque Revival Bowery Bank Building was converted years ago to the Cipriani restaurant and grand event space. The interior is 65 feet high, 80 feet wide and 197.5 feet long and is built from marble, limestone, sandstone and bronze. Both the original Bowery bank building downtown at 130 Bowery and here are considered two of the great event spaces in NYC. Years ago, I took a look, but was shooed out by a guard, a natural response to a lone figure scuttling about with a camera!

The IRT subway has served Grand Central Terminal with 4, 5, 6 and 7 train service since the late 1910s. There’s another grand private subway entrance further south on Park Avenue–and it’s almost too good to be believed.

Next door, the 1929 Chanin Building, at 122 East 42nd Street, features a gilt bas-relief designed by Edward Trumbull running around the facade, and distinctive signage including this font.

Back on the block where I worked, East 45th between 2nd and 3rd. One of the more famed of the restaurants of what was once known as “Steak Row” was the Pen & Pencil, where Hunsecker/Winchell-esque columnist (though nicer and more journalistic) Earl Wilson once held court. His New York Post columns were punctuated by a daily photo of a busty film or Broadway diva and his tagline, “That’s Earl, brother.”

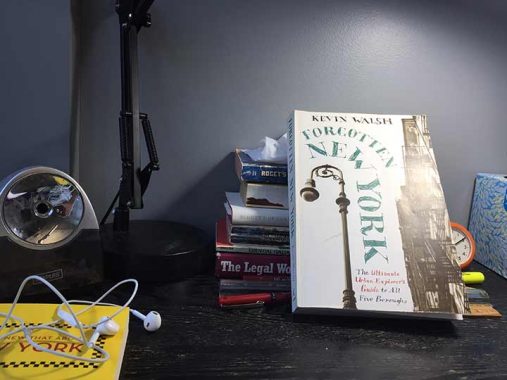

A look at my work desk at Summit. I brought in FNY The Book for the day guy, who came in at 8 AM when I was leaving; I had gotten him interested in Forgotten NY The Concept.

In the 1980s, when heading to work, I noted this large, handsome building on the south side of E. 45th at #132. Then as now, it’s home to the NY Health and Racquet Club (though I never went in; I have not seen the inside of a gym since high school). In 1915 it was built as The Central Club for Nurses and YMCA, and by 1962 it was the Morgan Hall YMCA. The Y sold the building in 1974.

A pair of “holdout” buildings at 3rd Avenue and East 45th. Late at night when there isn’t much traffic and it’s quiet for a few minutes, close your eyes and perhaps, you can hear the faint hoofbeats and shouts of the farmers and workmen who once ran their carts and wagons up and down the Eastern Post Road, which ran right through here some 200 years ago.

This was the deli where I got a Diet Coke and yogurt around 3 AM when I worked on the block from 1982-88 and again in 2018.

Here’s a pair of holdover brick buildings on the north side of East 45th, at #137 and #139. Both buildings have Asian restaurants on the ground floor, while #139 has a piano bar, Uncle Charlie’s, on the 2nd floor. But as I passed the building at about midnight I couldn’t help wonder what was going on in those dimly lit rooms on the upper floors, behind those tattered awnings of #137.

#139 was once home to the Press Box Steak House, one of a number of steakhouses in the area that catered to both the news industry and the showbiz crowd; the vanished #151, next door, was another, Danny’s Hideaway. East 45th came to be known as Steak Row in its heyday beginning in the 1920s.

I found an unusual installation in the window at #222 East 46th, a townhouse called the Blue Building, which comprises three “holdout” buildings constructed in the 1860s and combined in 1924. The exhibit commemorated the 1930 death of a milk dealer who lived in the building. It is an art gallery and event space.

Although there’s no surface Park Avenue between East 45th and 46th Streets, pedestrian traffic to and from Park Avenue can proceed via two passageways beneath the Helmsley Building, constructed as the New York Central Building [Warren and Wetmore, arch.] in 1929. Just two years later it was the site of a mob hit as Lucky Luciano and Vito Genovese-hired assassins rubbed out “boss of all bosses” Salvatore Maranzano. It acquired the Helmsley name after Helmsley-Spear, owned by Harry Helmsley and his wife “Queen of Mean” Leona, bought the building in the 1980s.

Around 8 AM after work one day in April, I got three shots of one of the last Twin Deskey 5th Avenue specials, first installed in 1965. This one is hiding in plain sight at 5th and 42nd street.

GCT’s track indicators are still blissfully “flippy boards” and not the computerized anodyne variety installed at Penn Station years ago. In fact, they still have reminders of an even older method of indicating station stops. Note the drawers toward the bottom of the stanchion: they were used to hold the various plaques on which the station names were printed before the track indicators became video boards or flippy boards. There was once a chain-and-curtain system inside the track indicator, and when the plaques with the names of the stops were placed in correct order, the trainmen (they were almost always men) rolled them into place by yanking on pulleys. The system was manufactured by the long-gone National Indicator Company in Long Island City.

Depew Place, off East 45th west of Lexington, a service alley under the Park Avenue viaduct. I covered it in depth on this FNY page.

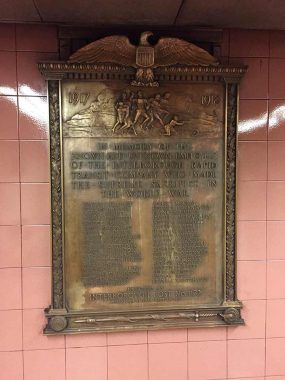

This plaque commemorated IRT workers who were WWI casualties. It could formerly be found by the escalator connecting the IRT Grand Central station to the #7 Flushing Line platform, but with recent station innovations, I don’t know its current situation.

The Oyster Bar is GCT’s most famed restaurant and has been here since the present incarnation of the grand train hall opened in 1913. From colonial times, NYC’s surfeit of oysters and shellfish made them a popular delicacy and oysters were consumed here at the same rate as other popular NYC treats like knishes or Nathan’s hot dogs. By the early 20th century the waters surrounding NYC had been “fished out” of the largest species, and the harbor was increasingly polluted. Nonetheless the Oyster Bar has persisted, importing the shellfish from other states. The Oyster Bar’s fortunes waned as the Terminal’s and NYC’s did from deferred maintenance in the mid-20th century, and wasn’t considered a prime dining destination. In fact, it didn’t really specialize in seafood and was in severe decline until Jerome Brody, who also operated the Four Seasons, took command in 1974 and brought back the old glory, which also included an architectural restoration that highlighted the primacy of its interlocking roof tiles, a trademark of the father and son Guastavino firm.

I’m not really a shellfish guy, but there other things on the menu and I hope to wind up in the Oyster Bar sometime.

I rode the #7 train to Woodside to get the LIRR after work between 8 and 9 AM. This allowed a good shot of LIC’s Silvercup Studio sign in full illumination.

Most people who ride the #7 train get a good look at the Silvercup Studios sign as the train inches past it before arriving at the Queensboro Plaza station. Currently it’s a TV production studio where many popular shows were filmed, like Person of Interest, Elementary and formerly, The Sopranos.

Before all that, though, Silvercup baked bread in this location between 22nd and 23rd north of 43rd Avenue. “When you came across this bridge, you could smell bread, twenty-four hours a day.” These words were spoken by Astoria’s own Christopher Walken. The bridge is the Queensboro Bridge, and the smell… well, it emanated from the old Silvercup Bakery at 42-25 21st Street in Long Island City. [boromag]

Walken would know — his family operated Walken’s Bakery on Astoria’s Broadway for many years. Gordon Bakeries sold bread under the Silvercup moniker and built this building which originally had 4 grain silos in the 1920s. Silvercup was sold until a 1975 strike forced the company to fold. The sound stages moved in in 1983, while Silvercup joined Bond, Taystee and other names in the NYC bread graveyard.

There are a variety of ways to get from the subway into the GCT to the streets outside, and I often chose the Graybar Passage, which is a corridor from the Great Hall through the Graybar Building to Lexington Avenue. I have recently written about the Graybar Rats, which are on a Lexington sidewalk canopy, but there are other quirks as well, such as this ceiling mural by Edward Trumbull, whose work also graces the lobby of the Chrysler Building across the street.

Trumbull’s Graybar mural predates his work in the Chrysler by four years, 1926 vs. 1930. The theme here, as you might expect, was modern travel. Unfortunately time has not been kind to the mural; the ones across the street were restored in 1999.

It’s the only remaining ceiling mural in the Passage. Other vaults featured paintings of blue skies and clouds, but were painted over quite awhile ago. Here, the mural shows scenes like an electric train, a bridge resembling High Bridge, skyscrapers and steel manufacturing, airplanes (including Lucky Lindy’s Spirit of St. Louis) and zeppelins, once thought of as a prime competitor to the airplane for air travel until the Hindenburg disaster.

Either the Graybar ownership group or the MTA should part with a few ducats and restore this Trumbull mural — his works in the Chrysler and Rockefeller Center have enjoyed such treatment.

I’m unsure whether I found this gorgeous gilded letterbox and mail chute at GCT or Summit Financial, but whenever you see one, it was likely manufactured by Cutler.

James G. Cutler, who received patent #284,951 for his design. which stated that the box must “be of metal, distinctly marked ‘U.S. Letter Box,'” and that the “door must open on hinges on one side, with the bottom of the door not less than 2’6″ above the floor.” If a receiving box was to be placed in a building that was more than two stories high, the bottom of the box was required to be outfitted with an elastic cushion to “prevent injury to the mail.” [Smithsonian National Postal Museum]

As paper mail diminishes in importance, I’m getting more and more into its physical aspects, such as envelopes, postmarks, and stamps. I am preparing an upcoming page featuring buildings that manufactured automatic stamping machines. I don’t have the wherewithal, or the time, to become a full blown stamp collector at age 67…but if I were younger…

Occasionally to get to the 7th Avenue subway lines and then to Penn Station I would take the Times Square Shuttle. I’ve written about it ad infinitum, but in recent years it’s undergone a lot of changes that included removing an entire platform, which FNY covered here. I don’t think I remarked that the Shuttle, o

As always, “comment…as you see fit.” I earn a small payment when you click on any ad on the site. Take a look at the new JOBS link in the red toolbar at the top of the page on the desktop version, as I also get a small payment when you view a job via that link. nce part of the original IRT from City Hall to 145th Street, uses cars with most of their seats removed to handle rush hour crowds. Well, it may have been a good idea before the pandemic. I seek out one of the 4 seats in the car anyway.

The walkway connecting the Grand Central Terminal to the GCT shuttle station was once part of the IRT trackbed; you can tell by the columns and girders.

A number of “doors to nowhere” abound at the Times Square shuttle station, one to the old Knickerbocker Hotel, another to the old Times Tower and another for which I can’t identify its destination. I believe the last two have been hidden since the station was renovated.

This may be one of the last photographs of the now-absent center platform. In 2021 the platform and center track were removed to streamline station operations.

Times Square Shuttle has always been one of my favorite station, as its exposed columns and girders give you a glimpse at century-old subway construction.

Most of the years I have been coming to the Times Square station — and I’ve been doing it since I was a little kid with my parents, so it’s over 50 years — there has been a record store in the station, between the stairs going to the BMT platforms handling the N/R/Q/W trains and the Shuttle area. And there was until just recently, till the Covid-19 Pandemic cooked Record Mart’s goose. I’d have to think that since there’s still a market for recordings pressed on vinyl some incarnation of a record store will return when the Pandemic is done.

The large mural at the TSS station was executed by famed Pop artist Roy Lichtenstein in 1994; it’s simply called “Times Square Mural.”

I’m a nostalgist and always find something to miss from long-gone jobs, friends etc. etc. When I worked at Photo-Lettering from 1982 to 1988 it was “second-shift” so I would arrive in midtown during the evening rush, as I began work from 5 to 7 PM. Making my way over to 216 East 45th I would take East 43rd sometimes and would thus pass St. Agnes Church. I noticed the church again on my way home one early morning recently.

However this St. Agnes is not the same building I passed all those years ago; the old building from the 1870s, constructed for workers on the original Grand Central Station, burned down in 1992, and what we have now is a somewhat anodyne building constructed in 1998, although it’s flanked by two of the old church’s remaining towers. I was surprised to learn that the painting behind the altar was done by Sean Delonas, the occasionally controversial editorial cartoonist for the NY Post from 1990-2013.

Archbishop Fulton J. Sheen (1895-1979) was based at St. Agnes and his riveting radio and later television sermons from the 1930s through the 1960s (“The Catholic Hour” and “Life Is Worth Living”) were recorded in a studio at the old church, as well as the Adelphi Theater further uptown.

Mayor Edward Koch subnamed East 43rd for Bishop Sheen between Lexington and 3rd Avenues in 1982.

Speaking of reconfigurations, here’s the old Penn Station LIRR corridor. Again, when I hit the shutter I had no idea of knowing that within 3 years it would be utterly different, with a wider corridor, higher ceilings, and new signage.

At the top you can see an artwork called “Eclipsed Time,” designed by Maya Lin of the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, DC. It was taken down when the station was reconfigured and is apparently seeking a home.

As always, “comment…as you see fit.” I earn a small payment when you click on any ad on the site. Take a look at the new JOBS link in the red toolbar at the top of the page on the desktop version, as I also get a small payment when you view a job via that link.

11/18/24

11 comments

Call me a Philistine, but I have never understood why railroad stations ever needed to be so overbuilt unless it was to gratify the ego of whoever was running the railroad. There is nothing inherent in its being a railroad that calls for its station to be palatial.

There used to be a lot more train traffic especially before the jet age.

In some cities, like Washington D.C., the various railroads that served that city, would create one station that would be used by several railroads. They were often called “Union Station”. That was not to memorialize the North of the then-recent Civil War, or organized labor, but to make it clear that several railroads had grouped into a “union” to build their common station. Such a station would be the grand entrance to that city, as was Union Station in our nation’s capital.

In New York, one of the most important cities in the country, the Pennsylvania Railroad and the New York Central Railroad were in stiff competition. Grand Central Terminal had long been the sole rail entry directly into Manhattan. The Pennsylvania changed all that by tunneling under the Hudson and East Rivers and built the Pennsylvania Station in 1910. Each company was vying for customers from the other, for both long-distance travelers and commuters. The grand designs of each offered facilities to travelers that we do not see there any longer. They included luggage handling (by Red Caps), taxi service that was indoors, hairdressers and barber shops, restaurants and many other services.

In high school we went to a dance at a school that was on the corner of Park ave.

and I think 82nd st.During the dance we got bored and decided to leave but before

we did we did a little exploring around and were down in the basement.There were

rooms down there just like in a regular apartment with furniture,bookcases,etc. and

on the wall facing the Park ave. side were these big windows with their panes painted

over.We opened one and there not 15 ft away were the tunnel and tracks of the then

Penn Central (or maybe Amtrak by then ) that ran under Park Ave.

You found Lex Luthor’s place.

One good thing about a lot of delis and convenient stores in NYC is that they’re open 24-7 so that even late night workers can get something when just about everywhere else is already closed by then.

A likely reason that the Railway Station Cafe had bullets and fonts that were not correct was to protect them from being sued by the MTA for copywrite infringement. What they used was close enough for non-nerds (unlike us real nerds) to associate with the real thing.

Midtown at night in the 21st century looks a hell of a lot safer and better lighted than Tribeca did in the 1960’s! I used to get off work at Western Union on West Broadway and Worth St at 1AM, and have to make my way to the Chambers St station to get home to Brooklyn. The streets were dark, and any other pedestrians were likely to be panhandlers, prostitutes, or muggers!

Can you do more night time pictures?

I’d have to go out at night. Nothing good happens after sunset.

I’m a fourth generation Manhannaite (82 y.o), and I truly appreciate your photos of the old stuff I saw as a kid.