![]()

SOME years ago, Kevin Walsh visited Haight Street in Flushing, comparing the sights of this obscure two-block road in an industrial corner of the neighborhood, with the scenic Haight Street of San Francisco. Not much has changed architecturally on either of these Haights since 2008. On my visit to the Haight of Flushing, I wanted to know the history of the Home Depot near this street. Such sizable commercial parcels are usually the domains of wholesalers, storage warehouses, and Amazon distribution centers. They have a history that speaks of the city’s past as a manufacturing hub, when things were made here by people who lived here.

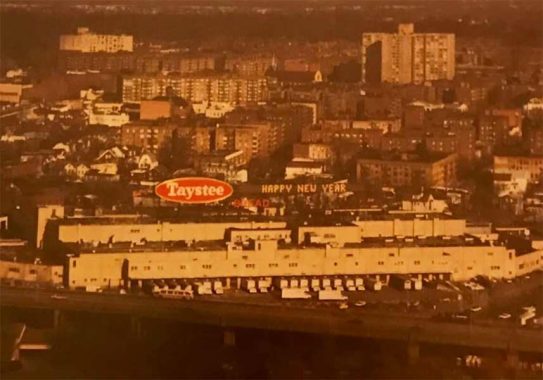

Prior to the Home Depot’s first store in Flushing, this eight-acre property was the Taystee Bakery, with 500 unionized workers making dough for the popular bread maker. When the last rolls rolled off the production line in 1992, the workers tried to buy the bakery and launch their own baked goods brand. But Stroehmann, the Pennsylvania-based company that acquired Taystee, instead sold the site to Home Depot. Financial incentives offered by the city were not enticing enough to prevent the outsourcing and layoffs as Taystee went the way of Silvercup, Wonder, and other Queens-based bakeries that departed the borough. Eventually, Stroehmann was devoured by the Bimbo Bakeries, which also owns Thomas, Entenmann’s, Arnold, and other recognizable names. The photo above is from the company’s promotional literature.

For a generation of drivers on the Van Wyck Expressway and passengers on airplanes bound for LaGuardia, the Taystee sign was a familiar part of the skyline along with the fragrance of baked goods. Drivers in this century can rely on the Home Depot sign and the big blue Cube smart Storage building as their references on this stretch of the elevated highway.

Prior to Taystee, this bakery was owned by A&P, a company better known for its chain of supermarkets which all closed in 2015. When it was built in 1962, it was the largest baking facility of its kind, with a weekly capacity of two million pounds of baked goods. With cheaper competition from other states, its long decline began a decade later until its closing in 1992.

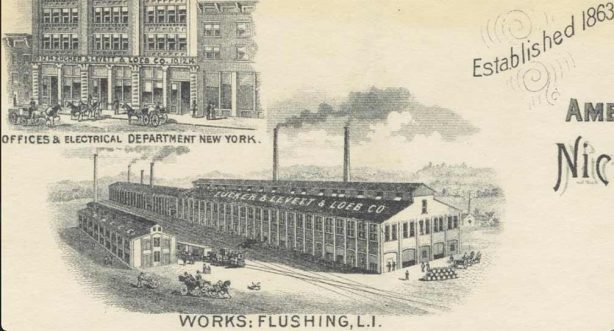

A map of Flushing in 1891 shows that this site has a long history of manufacturing. Zucker & Levett & Loeb had its factory here, producing chemicals, electric plates, and motors. A letter written by the company in 1894 shows its factory and Manhattan headquarters on the letterhead.

[Speaking of letterheads and billheads, see Inconspicuous Consumption’s Paul Lukas’ recent entry. You may have to pay admission to see the whole thing — Ed.]

Further back in 1873, before the first factory was built here, a block to the south of the Home Depot site had homes on Fowler Avenue. Its namesake was Thomas Fowler, a blacksmith who owned land here prior to development. Nicknamed Fowlerville, its location next to the marsh made it less desirable. Most of its homeowners had names such as Kelly, Kehoe, Higgins, and Reidy, which could explain why the nearby stream had the name Ireland Mill Creek. The last single-family home on this block, seen here in 2013, bit the dust in favor of an eight-story apartment building. Prior to the rezoning of Fowler Avenue, an archeological study was conducted in 2010, describing in detail the block’s history.

The 1873 F. W. Beers map shows Fowlerville on the edge of Flushing Meadows with the newly-built Central Line running past it. Haight Street was mapped here as First Street on land owned by Alfred Poppenhusen, son of the famous College Point industrialist. Another track seen here is a thin line indicating the White Line that operated from 1873 to 1876, abandoned as redundant because it ran parallel to the Port Washington Branch.

The most prominent address on Fowler Avenue today is the Al Oerter Recreation Center, built in 2009 as part of the Flushing Bay SCO project, that built a massive stormwater retention tank under the fields on the eastern panhandle of Flushing Meadows. The rec center is named for a four-time gold medal Olympic discus throw champ who was born in Queens. Where houses and small industries stood, Fowler Avenue is now almost entirely lined with post-millennial apartments.

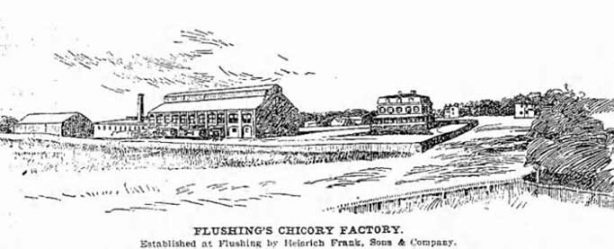

The 1917 Sanborn property survey shows Heinrich Frank Sons & Company having a chicory and substitute coffee operation at this site. The German company established its Flushing facility in 1894, producing two million pounds of this vegetable by 1900. During World War One, it was confiscated by the government and later returned to the company. Frank sold its Flushing factory in 1946 and it later became the Taystee bakery.

The factory had a dedicated freight spur connecting to the nearby Port Washington branch that served its needs. Its presence connected to Flushing’s past when it hosted a famous plant nursery, and its 20th century manufacturing period. These tracks were a stub of the Central Railroad of Long Island, constructed in 1873 by department store magnate Alexander T. Stewart. It ran from Flushing to Garden City through present-day Kissena Corridor Park. Art Huneke’s refreshingly old-school ARRts ARRchives Long Island Railroad site, has a detailed section on the CRRLI. The last passenger train ran here in 1879, as one of the shortest-lived railroads in the city.

Looking at the junction of the Central Line and the Port Washington branch in 1929, we see Frank’s factory to the side, where Home Depot stands today. The houses in this photo are on Haight Street, virtually unchanged a century later but surrounded by urban density. Had this train line been revived, it would have meant a direct ride from Floral Park to Flushing, across a swatch of Queens that is dependent on cars and buses for commuting.

The bakery was demolished in favor of Home Depot but next to it, the Gamco glass factory is doing well with so many of the city’s post-millennial towers sheathed in full-length windows. The driveway behind the factory runs on the path of the Central Line and one can imagine boxcars lining up to this building in the early part of the last century.

In 1929, the Queens Borough President’s Office surveyed the route of the Central Line, perhaps for a revival that never happened. Looking east from Frank’s factory, the trench appeared without tracks. It shows a tunnel fit for one track underneath College Point Boulevard, known then as Lawrence Street. It was buried entirely in the coming decade.

Looking west from the same spot, we see the Roosevelt Avenue Bridge, which was completed in 1927. A lone freight car stood at the end of the spur track, facing towards a route unused in a half century.

There is a different “tunnel” on this spot, where trucks drive inside the glass factory on the driveway where Stewart’s trains once ran.

The food history of this block continued after Taystee’s departure with a sizable Western Beef supermarket that recently became Fei Long, preserving the colors of its predecessor’s logo in a feeling of continuity.

On the east side of College Point Boulevard, the track ran along Ireland Mill Creek, on the site of Queens Botanical Garden. Robert Moses turned the former train line into a set of corridor parks that connected Flushing Meadows with Kissena and Cunningham parks, a precursor to the rail-trails of the late 20th century. After the tunnel was buried, the portal site became parkland, sandwiched today between apartments and a pumping station. On the map, it lines up with the route of the Central Line.

On the border between the Home Depot parking lot and the Gamco factory, one can imagine tracks on this driveway, a phantom rail line that operated for only six years.

In total, there are 20 Home Depots in the Five Boroughs, as of early 2025. They appear identical but each site has a unique history. This one involved a short-lived railroad, imitation coffee, and baked goods.

You can learn more about the history of this neighborhood by visiting each of the hyperlinks posted in the essay above.

Sergey Kadinsky is the author of Hidden Waters of New York City: A History and Guide to 101 Forgotten Lakes, Ponds, Creeks, and Streams in the Five Boroughs (2016, Countryman Press), adjunct history professor at Touro University and the webmaster of Hidden Waters Blog.

As always, “comment…as you see fit.” I earn a small payment when you click on any ad on the site. Take a look at the new JOBS link in the red toolbar at the top of the page on the desktop version, as I also get a small payment when you view a job via that link.

1/11/25

9 comments

A famous taystee story occurred near the beginning of the 64 fair

Taystee bordered on fair property and they took

Advantage by placing advertisements in plain sight of

Fairgoers. Robert Moses was angered by the ads and had his fair workers erect multiple fair banners to block the

ads.

Great history lesson, Bravo!

Hi. The facility was an A & P bakery during the ’64-’65 world’s fair. The rooftop signage was the beautiful old-school A & P logo neon with the tagline ‘Jane Parker baked goods’. Robert Moses requested that the signage be turned off while the fair was in season, claiming that it distracted from some of the exhibits. A & P did not oblige.

Interestingly enough, I pass by this whenever I go to and from Mets games, but I never the knew the story about such a place.

That’s why we have Forgotten-NY, to share these stories.

Nighttime aromas from the bakery are ingrained in my memory.

My grandfather used to be the head of HR and then in plant management at the A&P bakery. Heard some interesting stories of interaction between him and the teamsters, specifically Jimmy Hoffa.

Interestingly, Democrats always talk about “good union jobs” but fail to recognize that 60-75% of jobs are not unionized.

I do remember the Taystee factory growing up as a kid in Flushing in the 1980’s, passing it on the Van Wyck Expressway with memories of the bakery smell as you mentioned. In addition, as seen in the top photo where it says “HAPPY NEW YEAR” this was a scrolling lights message board that gave information like news headlines, community events, or the weather.