By PATRICK O’CONNOR

Guest post

I’ve always been fascinated by the inaccessible islands of the New York City archipelago. I purposefully use the term inaccessible rather than abandoned. Many of the smaller islands around the City, had some development, and their facilities were abandoned to the forces of nature. Hart Island certainly has its share of remnant structures but there is still continuing important activity and thus not abandoned.

Hart Island’s name is questioned. Some say the Island resembled the shape of the human heart. Another interpretation is that hart is the Middle English word for deer which populated the island. Its most notable use is as a potter’s field, for unclaimed decedents and those whose family cannot afford a burial. NYC Human Resources Administration handles about a thousand cases per year in an orderly manner to track locations of burials for those who may wish to find their loved ones. Over one million have been interred since its inception.

Hart Island’s past and present are brought to life by tours offered by the Parks Department Urban Park Rangers who have been offering free tours with admittance by lottery since 2023. The tours not only shed light on the burial process but also provide insights into the vast array of other uses of Hart Island since the 1840s.

Those hoping to visit, apart from those who have loved ones interred there, can apply for the Parks Department lottery at https://www.nycgovparks.org/events/hart-island. DOT operates the ferry at the foot of Fordham Street on City Island, steps away from the City Island Nautical Museum. This tour focused on the north end of the Island and Parks Department alternates tours that focus on the north and south ends of the Island every two weeks.

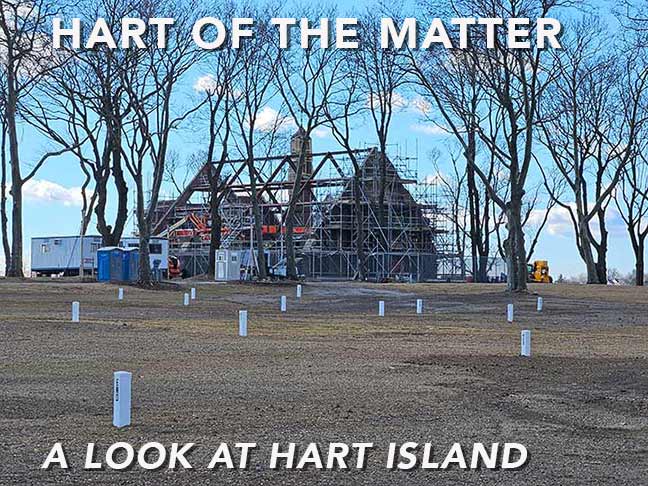

Disembarking, we see the remnants of the Interfaith Chapel, constructed in 1935 by Catholic Charities during the time when prison inmates performed the burials, and its use ended in 1966 when the prison workhouse was closed. As you can see, there is a much-needed reconstruction is underway. White markers indicate the various sections of the grid for ease of locating specific burials.

Walking to the east, we crossed a field of graves without boundary markers that date to the 1860s. Undulations in the surface indicate the decomposition that has occurred over 160 years. Softness in the ground due to recent snow melt created an uneasy feeling while passing.

The Union Army set up a training base for recruits in 1860 and also a camp for confederate POWs, in addition to burials. Union Soldiers originally interred there were reinterred. A monument stands to honor the fallen and the inscription on the back reads: “The remains of these veteran union soldiers and sailors were disinterred on June 9, 1941 and reinterred in the Cypress Hills National Cemetery.”

From a distance, we can see the remnants of a former prison sited on the Island. A warning sign is painted on the outside to deter unwanted visitors approaching from Long Island Sound.

Walking toward the north end of the Island, we come to an ironic pairing of features. First, we see a structure known as the Peace Monument, erected in 1948, as a remembrance of World War II. U.S. Naval presence on Hart Island precipitated its placement and construction was performed by inmates. Credits, at the base, are given to, then Mayor William O’Dwyer 1946-1950 and Department of Corrections Commissioner Albert Williams 1947-1953.

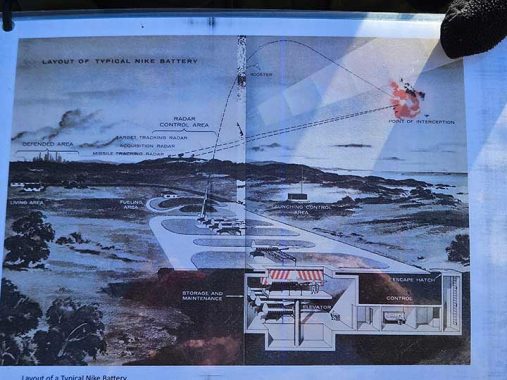

Sitting on the top of a hill, the Peace Monument overlooks sites of two former Nike missile bases constructed in 1955. Products of the cold war, Nike missiles served as a defense system, ready to intercept incoming ballistic missiles. A park ranger held a rendering of the layout of the missile bases. Access to the vaults is prohibited and much rehabilitation is required to make the structures safe for the public.

At the extreme north end of the Island, we encounter a remnant structure that stumps the experts. At one time it was believed that this structure was a Civil War era receiving station for decedents. Testing of the materials of construction revealed that the date of the structure was 20th century, contradicting the previous theory. Search for the use of the structure continues.

There were other uses of the island to be discussed on the tour of the south end of the Island, including an infirmary for those with infectious diseases, the original location of Phoenix House, burial plots for those lost to AIDS and COVID epidemics, bare knuckle boxing matches and the story of real estate mogul Solomon Riley, whose dream, in the 1920s, was to build what he called the “Negro Coney Island” as nearby amusement attractions were segregated. This dream was dashed when the City took over the property by eminent domain.

Views from Hart Island

For more information, see the Hart Island Project

Patrick O’Connor is a lifelong resident of Queens, retired with 40 years of service for City of New York Department of Environmental Protection, a licensed sightseeing guide in New York City and a recent addition to the Board of Trustees with Queens Historical Society.

As always, “comment…as you see fit.” I earn a small payment when you click on any ad on the site.

2/5/25

14 comments

In this video about Hart Island from 1978 you can see a ball field where inmates used to play. The seats at the field are from Ebbet’s field.

I am extremely curious about what happened to those seats.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qrjzKYT6oag

There is a YouTube channel called Two Feet Outdoors where the content creator kayaks to many of these remote isolated places in the NYC region, and Hart Island was one such location– no, he didn’t land, he just paddled by.

Great channel – Matt just won a lottery to tour Hart Island and recently put up a 1-1/2 hour video of the tour, fascinating island.

When I was a Cub Scout, the pack I belonged to visited a Nike base located in Lido Beach, NY. It was an Army installation. A radar technician’s demonstration didn’t include a launch, but he tracked an overflying airliner for us and explained that if it was identified as “hostile,” a Nike would be launched to intercept and destroy it. A few years later (1962), during the Cuban Missile Crisis, I’m guessing that civilians couldn’t get near the base for obvious reasons.

Looking forward to many more interesting articles,hopefully.

I remember a News article back in the ’70s describing life on the island.Theres only so much

room to bury people so sections of land have to be rotated,kind of like crop rotation,When the

remains of one section have been felt to have been sufficiently disintegrated then that section is ready

to accept recent arrivals and the cycle is repeated.The article described one inmate working there who

lost his balance and fell into a grave that was still putrefying and the guy was freaking out going Yaaaaahhh

get this crap off me!!! while the other inmates smirked and laughed

Cemetery “crop rotation” is fairly common in parts of Europe and Asia, where space is at a premium.

During a visit to New Orleans many years ago, I was surprised to learn that the above-ground family mausoleums act in a similar manner. Bodies were placed on a shelf and the high heat and humidity took their toll over a few years, decaying the bodies. When space was needed for additional family members to be interred the dusty remains were pushed to the back of the slab, where they would fall to a pit at the bottom.

I have a stillborn baby sister and baby brother buried there in the early 1960’s. Unfortunately, I don’t know exactly where, as an arson fire in 1977 destroyed the burial records.

I remember going on a Boy Scout hike in the Rockaways. We hiked through Riis Park and then had to pass around Fort Tilden, where Nike missiles were located, to proceed to Breezy Point and Rockaway Point.

I believe the missiles were removed about fifty years ago.

To Tama Harbor: My stillborn baby brother was buried there in 1943. I was able to get a record a couple of years ago from one the government departments. I don’t remember which one, it may have been the Department of Health. If you call them, they can refer you if they’re not the one.

when youre comment gets scrambled and chopped up that means you have incurred

the wrath of the almighty

I feel that this isn’t too much to see on Hart Island especially since most of it is a cemetery to start with.

That’s because many of the decaying buildings were demolished in recent years.