SOMETIMES, walks determine their own endings. I felt like a walk in Prospect Park, where I hadn’t been for awhile (in my young years, things were more dangerous and so, between the occasions when one parent or the other took me on bus rides on the B16 (Fort Hamilton Parkway/13th Avenue) which ended at the park, and the 1980s, when I excused myself on Sundays to skip the end of yet more NY Jets losing efforts, I was rarely in the park, or the nearby Green-wood Cemetery. The park and the cemetery were developed in the mid-1800s very close to each other, so mid-Brooklyn “breathes” with the oxygen emitted by plants more than any other part of the borough, except for the cemetery belt in Cypress Hills. I began at the F train station on 15th Street at the SW end of the park, eventually winding up at the east end of the park on Ocean Avenue, and then decided to continue on, to a subway stop where I had never caught a train before.

I decided to see some more of Windsor Terrace, which I have always admired for its relaxed pace and varied architecture. I didn’t go into the park right away as I wanted to walk some streets I hadn’t walked before which I always strive to do when out with the camera. I know, or knew, at least four people who have walked every street in NYC end to end including Matt Green and Bill Helmreich (RIP) but I just don’t have the patience for it. By my estimation I’ve covered about one third, or 33%, of all NYC streets.

Google Map: Windsor Terrace to Lefferts Gardens

I have lately taken more of an interest in the tiled and mosaic signage in IND stations: I like the bold colors and type fonts, of which I’ve never determined a name but are instantly recognizable as the IND subway fonts. I have been paying attention to the directional signs on the staircases, like this one, painting to the staircase going to Prospect Park West. At 15th Street the main ID signs are gold with brown trim and the directional signs have brown tiling.

The F train trackage is on an IND line built in the 1930s, to its original terminal at Church Avenue. In 1954 a connection was made to the Culver BMT elevated, built in the 1910s and going south to Coney Island.

Here and there, some IND structures can be found aboveground, as on this subway entrance stair, with two Machine Age-styled lamps. Both sport green globes, indicating this stair is open for entrance at all times. In one of the shots, three types of lamps can be seen, the green subway lamp, the Corvington street lamp and the Type B park lamp.

The Nitehawk Cinema reopened as the Pavilion in 1996, after several years of moribundity. Until the mid-1970s, it had been the one-screen Sanders Theatre, opening as the Marathon in 1908 by brothers Harry and Rudolph Sanders and retooling capacity as the renamed Sanders in 1928. I saw “Independence Day” here in 1996.

At Prospect Park’s entrance at Bartel-Pritchard Square (see below) you will find two massive columns. Inspired by the 400 B.C. Acanthus Column of Delphi, they feature granite acanthus leaves snaking around the columns and on the capital, topped by bronze lanterns. They were designed by famed architect Stanford White in 1906.

Prospect Park opened in 1867 and was completed in 1873. Maps show there has always been a traffic circle in this spot since the park opened, and the apartment buildings on Bartel-Pritchard Square were built along the gentle curves of the circle. The “square” was named in 1923 for Emil Bartel and William Pritchard, two young Brooklyn natives who were killed in combat in World War I. Bartel was a Windsor Terrace native while Pritchard was from Bushwick. The polished granite memorial to Windsor Terracers killed in combat was placed here in 1965.

Prospect Park West continues from Bartel-Pritchard Square a few blocks southwest to Green-Wood Cemetery, even though at those blocks there is no Prospect Park for it to be west of. It has been thus for a century or more; the oldest maps I have show a 9th Avenue in Prospect Park West’s place all the way to Grand Army Plaza, but later, the whole kit and caboodle switches to Prospect Park West; there was never a situation that had a 9th Avenue for a few blocks between Bartel-Pritchard and Green-Wood. A NYC quirk.

There are three varieties of pavement in Bartel-Pritchard Square and also at the entrance along the columns: Belgian blocks used in the past as street paving; hexagonal blocks used on sidewalks at NYC parks (which are difficult to walk on); and buff herringbone blocks, reminiscent of the designs employed in tiling invented by Spanish engineer Rafael Guastavino.

The square has two varieties of street signs: regular green and maroon Landmarked district signs.

I always pay attention to sidewalk signage, which has become more imaginative in recent years. 209 Station, sporting what looks like a handcut wooden sign is a beer and liquor distributor, while on the corner of 16th and Prospect Park West, Betty is a popular bakery.

In addition to the pavements in Bartel-Pritchard Square, Prospect Park West has its own dark red brick paving, installed during a renovation several years ago. Cambridge, MA and other cities also have sidewalk red brick paving (but better).

Some say that Windsor Terrace begins at Farrell’s, the venerable (1933) institution at Prospect Park West and 16th Street, where, despite the neon sign, there hasn’t been a grill for years, though you can get corned beef sandwiches on St. Patrick’s Day. There’s no table service at all – you drink at the bar. If you were female, you didn’t drink at the bar until 1972, when Shirley MacLaine swept in with her then-boyfriend, Park Slope’s Pete Hamill, and demanded service, ending the outdated tradition.

At first I was mystified by the metal object in the street, but I was later informed it was a cooker built for smoking meats. The cooker belongs to Babysmoker, which sets up at Farrell’s on Fridays.

I have often remarked in FNY that liquor stores maintain some very old signs, even keeping them when letters fall off or the neon quits. If the word liquor can be made out, there’s no need to replace the signs. the same is also true of laundromats, or in this case, “Laundercenter” in which the letters are made of cut wood.

Krupa Grocery is actually a full service restaurant; according to locals, there was once a grocery in this space. According to the Krupa website, neither of the founders are named Krupa; however, the shingle sign is shaped like a drumhead, so perhaps the place is named for famed mid-20th Century Big Band and jazz drummer Gene Krupa.

Update: new info on both Krupa Grocery and Prospect Park West. See Comments.

Before going east on Windsor Place, I noticed the stoplights and lampposts are painted very light brown. Standard aluminum poles are generally painted gray, but you see green, black or dark brown in some neighborhood economic alliance districts; but light brown, seen here, is unique.

Windsor Terrace, the narrow neighborhood between Prospect Park and Green-Wood Cemetery, and Windsor Place are generally accepted to have been named by some long ago developer for Windsor, England as well as the surname of the royal family. In the early 20th Century developers imparted a “touch of class” by applying British place names to streets and neighborhoods. See the neighborhoods and streets south of Prospect Park for the full flower of this trend.

East on Windsor Place, I found some well-kept, 3-story brick walkup buildings that I call “the bread and butter of Brooklyn residential buidlings.” How convenient it must be to emerge from the 15th Street station and head right in.

In the Park Slope area, one-block streets are found in pairs almost exclusively. Fuller and Howard Places first appear on maps in the 1880s or so; property records show that the residences on both sides of Fuller, and the south side of Howard, were built in 1915.

The pair run between Prospect Avenue and Windsor Place between Prospect Park West and 10th Avenue. Both places are populated with two-family brick buildings, with porches on the ground floor. With abundant street trees, those porches are the perfect place to hang out on an August afternoon with a beer or a lemonade.

Well-reviewed thrift shop True Love Always, specializing in household goods and LPs, likely took a cue from another famed shop in the same genre, the former Love Saves The Day in the East Village (1966-2009)

10th Avenue is subtitled John P. Devaney Boulevard, after a hero firefighter who perished in 1989. Previously the Department of Transportation made the unfortunate decision to place both names on the same sign, making both rather illegible: but it’s got nothing on Fresh Meadows, where Jewel Avenue and Harry Von Arsdale, Jr. Avenue appear on the same sign (though newer signs place the names on separate signs).

Attached houses on Windsor Place between 10th and 11th. It appears a single developer built this side of the street in an era when esthetics and style were given more emphasis. There are a variety of roofline treatments, and each house has either an indoor or outdoor porch. I’d have a hard choice if I had to decide between an indoor or outdoor porch. I suppose I would go with outdoor to feel a cool breeze in the summer. There would of course be an overhead fan.

Update: This block, and others in Windsor Terrace, were developed by U.S. Congressman William M. Calder, as discussed in these Brooklyn Eagle items from the 1910s supplied by Edward Fitzgerald. In fact the area was briefly known as “Calderville.” A short street connecting 17th St. and Prospect Avenue was constructed at the same time as Prospect Expressway and was named for him.

Sun angle and foliage prevented me from getting the best shot of PS 154, the Windsor terrace School. It’s a classic from 1908 designed by prolific schools architect C.B.J. Snyder. When water damage was repaired, the construction company’s website got a better shot, and here is the school on Street View.

I entered the park, finally, at Vanderbilt Playground, Prospect Park southwest at Seeley street, and hiked by the man-made Prospect Park Lake, which is 55 acres but only seven feet deep. Nonetheless, it’s stocked with multiple species of fish including largemouth bass, black crappie, yellow perch, chain pickerel, bluegill, pumpkinseed, common carp, and golden shiner; fishing is permitted with the proper license.

Wellhouse

On the drive past the lake, unmarked but shown on maps as Wellhouse Drive, note the small stone-and brick structure on your left as you walk east. It is the Prospect Park Well House, built in 1869, that once housed engines and machinery that once pumped 750,000 gallons of water a day into a reservoir that fed the park’s gullies, springs and lakes. The water source was a well some 70 feet deep and 50 feet in diameter directly under where you are standing, if you are facing the wellhouse. A smokestack 60 feet tall was affixed to the back of the building. After city water entered the park, the reservoir and smokestack were torn down in the 1930s, and the well was covered over, though it’s still down there. Until recently the wellhouse was probably the most ignored of Prospect Park’s older structures; it didn’t share in the various reconstructions and reappointments many of the park’s other buildings enjoyed in the 1990s and early 2000s. Fortunately in the late 2010s the situation was rectified as the Wellhouse received a welcome $2.5M renovation that features NYC’s first public non-flush compost toilet.

In the 1880s in the vicinity of the Wellhouse and nearby Terrace Bridge (see below) was a kiosk containing a camera obscura, a dark chamber on which an image reflected from a revolving mirror in the roof was projected on a flat white table. The camera obscura lasted only a few years, however.

Be careful not to miss the Maryland Fighters Memorial, as it’s set way back on the hill looking west from Wellhouse Drive. The monument, a simple granite Corinthian shaft with a sphere at its apex designed by Stanford White, is at the foot of Lookout Hill at the bottom of a staircase along Wellhouse Drive in a relatively inconspicuous area. It is a tribute to the Maryland regiment under Lord Stirling who occupied the British long enough to allow colonial forces to slip past them at the Old Stone House (which can still be seen in reconstructed form at J.J. Byrne (Washington) Park between 4th and 5th Avenues and 3rd Street a few blocks away from Prospect Park).

The memorial was erected August 17, 1895, the 119th anniversary of the battle. Like many monuments, it fell into neglect and disrepair, but was restored with assistance from the state of Maryland in 1991. On the base, you can read George Washington’s purported quote as he watched the battle (and dispatched orders by courier) with his spyglass from what is now Cobble Hill: “Good God, what brave fellows I must this day lose.”

Terrace Bridge takes Wellhouse Drive over the Lullwater, the northern arm of the Lake. Unfortunately the bridge walkway itself has been uglified by port a potties and construction vehicles, so I’ll show you the brownstone railing. The present Terrace Bridge replaced a wooden bridge in 1890. Most of Prospect Park’s bridges are picturesque, though, and I’ll quote from my Prospect Park Bridges page from 2001:

Terrace Bridge is the residue of much more grandiose plans and dreams that went unfulfilled.

Clay Lancaster in Prospect Park Handbook:

A terraced platform adjacent was to be provided with seats and awnings, and a small building ‘for the special accommodation of women and children, at which they may obtain some simple refreshment.’ An elaborate Eclectic stone tower was to have been built here, too, affording an even better vista of the bays and surrounding lands to the west…Midway between here and the Lookout, at the head of the inlet…was to have been built the Refectory, with broad arched terraces overlooking the water. The name of Terrace Bridge nearby recalls the project which, like the proposed structures on Lookout Hill, expired before realization. The Refectory was to have been ‘the principal architectural feature in the park’, like a well-appointed inn in the country.

The Refectory was one of Frederick L. Olmsted and Calvert Vaux’ ideas that never left the drawing board, however, due to a financial ‘panic’ in 1873.

I was in a bit of haste and did not have time to fully inspect the Oriental Pavilion, but don’t miss it if you’re in the Park’s east end. The Pavilion was completed in 1874 and consists of eight cast iron posts, painted colorfully in a vague Middle Eastern pattern, supporting a complex roof that flares outward on the edges, creating a large shady area. Don’t forget to glance at the roof when standing under the Pavilion: you will be rewarded with a beautiful stained-glass octagonal skylight. In 1949, NYC’s Parks and highways czar, Robert Moses, gave the order that a snack bar be constructed under the pavilion in a brick enclosure. The snack bar caught fire in 1974, destroying much of the structure, and it remained a ruin until the city found enough funds to restore it in the 1980s. It has since been restored again.

The Pavilion has been renamed the Concert Grove Pavilion (for the nearby park attraction) from Oriental, which simply means “eastern” as it is in the eastern end of the park; but the word has attained a bad racial rep for some.

Washington Irving (1783-1859), who met his namesake George Washington while a young boy, was popular both in the States and in Europe for his essays and fiction, and was the creator of Ichabod Crane, Rip van Winkle, and the tricornered Father Knickerbocker, NYC’s mascot. He is remembered in bronze bust at Washington Irving High School, across the street from a building with a plaque stating that he lived there but never did; a second bronze bust at the Hall of Fame of Great Americans in the Bronx; Irving Place in Manhattan and Irving Avenue in Bushwick; and here in Prospect Park, with a third bust near the Lincoln Road entrance/exit.

The bust was sculpted by James Wilson Alexander MacDonald (1824–1908) in 1871 and restored in 1997.

Exiting the park and heading into Lefferts Gardens, named for a Dutch colonial family whose farmhouse stands nearby in Prospect Park. Ocean Avenue is one of those Brooklyn roads named for where it goes; beginning at Flatbush Avenue and Empire Boulevard, it curves south and runs directly south to Emmons Avenue at Sheepshead Bay, and there’s another short section in Manhattan Beach that goes to the Atlantic Ocean. Not to be confused with Ocean Parkway.

Taking advantage of park views, some incredible residential palaces were built on the uninterrupted stretch of Ocean Avenue between Parkside Avenue and Lincoln Road.

The NYC subway has its share of “station houses” originally built to let people wait for trains, if they didn’t want to do so on the platforms, if they chose. The ones constructed at Bowling Green and 72nd Street in the initial phase of subway construction in the 19-aughts have gotten the most ink and attention from train buffs. They’re fine creations.

But I also like the ones added later on BMT lines built by Brooklyn Rapid Transit (later the Brooklyn-Manhattan Transit) in the initial rollout of the “Dual Contracts,” a large subway initiative in 1911 that saw the majority of IRT and BMT subway lines constructed over the following decade.

I am unsure that these simple, basic “Arts and Crafts” stationhouses were the work of Squire Vickers, who took over as chief subway station designer after Heins & Lafarge passed the baton in 1908 and continued on through the IND era of the 1930s, but no matter who designed them, I’m a big fan of the tiled interiors with subtle coloration differences. This one at Prospect Park, at Parkside and Ocean Avenues, even retains its original lamp sconces.

This station is on the Brighton line (B, Q) but you can also find one at 9th Avenue on the West End (D) and there are quite a number of them on Sea Beach line stations (N) between 8th Avenue and 86th Street.

On the east side of Flatbush Avenue just south of the Prospect Park entrance at Ocean Avenue is the former Bond Bread factory (slogan: Bond Makes Good Bread) whose baking aromas used to suffuse the neighborhood, greeting Brooklyn Dodgers fans en route to Ebbets Field. It was a bakery from 1925, when it was built, to the 1960s. While the ground floor houses a retailer/wholesaler, the rest of the building awaits restoration.

This is the back end, at Bedford WashingtonAvenue and Sterling Street; you can see the front on this page.

The tall tower at Bedford Avenue and Empire Boulevard is part of the central fire communications and telegraph station for the borough of Brooklyn; all fires called in via the red fire alarms located on every other block (for the most part) were routed through here. These days, most fire calls are made via 911.

So far, fast food chain Sonic has not made a big push into NYC; in fact this is the first freestanding Sonic I’ve seen, at Empire Boulevard and Bedford.

Originally a walk-up root beer stand outside a log-cabin steakhouse selling soda, hamburgers, and hotdogs, Sonic currently has over 3,400 locations in the United States. Sonic is known for its use of carhops on roller skates, and hosts an annual competition (in most locations) to determine the top skating carhop in the company. The company’s core products include the “Chili Cheese Coney”, “Sonic Cheeseburger Combo”, “Sonic Blasts”, “Master Shakes”, and “Wacky Pack Kids Meals.” [wikipedia]

I don’t know if there are any carhops at its Brooklyn location. Sonic, which has nothing to do with the video game hedgehog, was founded in 1953 as the Top Hat Drive In by Troy Smith in Shawnee, OK, changing its name to Sonic Drive-In in 1959 when faster than sound travel had gotten the public’s attention.

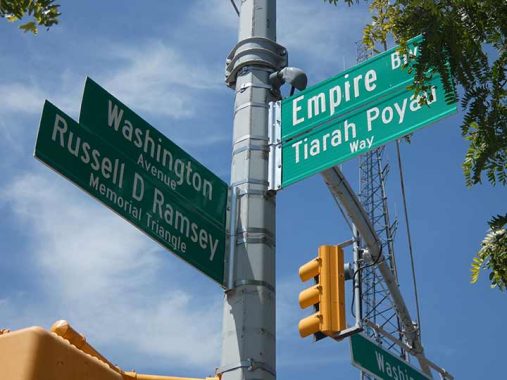

Honorific signs honoring local notables have proliferated in recent years. As a rule, the honoree must be deceased.

According to oldstreets.com:

Russell D. Ramsey (1929-1992) joined the NYFD as a Fire Alarm Dispatcher and was the first African American to be promoted to Chief Dispatcher. He was also an expert on firehouse history and architecture, and served on advisory committees of the New York Fire Museum and the Brooklyn Historical Society.

Meanwhile, Tiarah Poyau was a 22-year-old student shot and killed during J’Ouvert (Caribbean Day Parade held on Labor Day) in 2016.

Though some signs carry them, periods are not used after initials on NYC street signs.

I’m one Brooklyn native not reminiscent about the Brooklyn Dodgers, since the Dodgers were in Brooklyn only just over once month of my life in 1957. The Dodgers, also known as the Robins for a few years, played at the stadium owner Charles Ebbets built for them in the block surrounded by Bedford Avenue (the outfield fence), McKeever Place, Sullivan Place and Montgomery Street from the 1913 to 1957 seasons; before the Jackie Robinson era began in 1947, their time at Ebbets was mainly a period of futility marked only by 3 National League pennants in 1916, 1920 and 1941.

During the Robinson era he was joined by Duke Snider, Gil Hodges, Don Newcombe, Carl Furillo and many other stars, and the Dodgers had an enviable run of domination in the National League. For the most part, they were stymied by the New York Yankees, their sole opponents in the World Series in those years, with the exception of 1955 when the unheralded Johnny Podres defeated the Bombers in the 7th game. The Dodgers suffered declining attendance and when plans for a new stadium downtown were thwarted by Robert Moses, Dodgers’ owner Walter O’Malley made the business decision to accept an offer to move the club to Los Angeles — where the Dodgers almost immediately won the World Series, defeating the Chicago White Sox in 1959. They won again in 1963, 1965, 1981, 1988, 2020 and 2024, beating the Yankees in 1981 and 2024.

Both Ebbets Field and the Dodgers’ enemies, the New York Giants’ homes have both been taken over by housing projects, Ebbets Field Houses and Polo Grounds Houses in upper Manhattan. Ebbets Field was razed in 1960 while the Polo Grounds became the temporary home of the New York Mets, surviving till after the 1963 season. A single staircase that took spectators from the Polo Grounds up Coogan’s Bluff remains.

I walked east on Empire Boulevard, as I had rarely done so before, taking note of the large storage facilities and warehouses in its western end in bold colors.

Empire Boulevard was named in 1918 after New York’s nickname, the “Empire State.” Prior to that, it was named Malbone Street; most of Malbone Street was renamed Empire Boulevard in the aftermath of a disastrous train crash on November 1, 1918 that happened under a Malbone Street overpass. The street was named for Ralph Malbone, a grocer who lived on Fulton St in the early 19th Century. He built a popular inn on Clove Road for passenger coaches going from Bedford to Flatbush and beyond around Montgomery St and developed that rustic neighborhood-which was then called Malboneville for at least 25 years or so.

Malbone Street was not always perfectly straight. After it was straightened, a small piece was left over west of New York Avenue,and that piece is still there. I discuss that, as well as Clove Road, a leftover from before the street grid was laid out.

Seeking a bit of shade, I detoured on Rogers Avenue to Sterling Street. I have overlooked Rogers Avenue over the years, but there’s some interesting architecture I should check out. Rogers Avenue begins at Bedford Avenue and Pacific Street, where you will find a monumental statue of President Ulysses S; Grant on horseback, and runs south through Lefferts Gardens to Flatbush Avenue. Though the photos are missing after 15 years, Montrose Morris (Suzanne Spellen) discusses the attached apartments at 405-425 Rogers, shown in the above Gallery, in this Brownstoner post.

Rogers Avenue from Farragut Road to Eastern Parkway was co-named Jean-Jacques Dessalines Boulevard in 2018 for the first leader of the independent Haiti (1758-1806).

The descendants of Lord Stirling can’t say he’s underrepresented in Brooklyn. As I have noted earlier at the Maryland Fighters Monument, General William Alexander, also known as Lord Stirling, led a company of 400 Maryland troops that engaged British General Charles Cornwallis’ force of 2000 grenadiers and cannoneers at the Old Stone House (the site of today’s J.J. Byrne Park in Park Slope) to cover the retreat and, while many of the Americans were able to escape, Stirling was captured and 259 of the Maryland troops were killed.

Somehow, the “i” in Stirling’s name became an “e” and both Sterling Street and Sterling Place, several blocks to the north, were given his name when streets were laid out in central Brooklyn in the early 1800s.

Portions of Sterling Street fall within the Prospect-Lefferts Gardens Historic District, designated by the Landmarks Preservation Commission, for its notable residential architecture.

I had never boarded a train at the Sterling Street station before; with the exception at the end of the line at Flatbush Avenue, I had never gotten on or off at any of the #2 train stations east and south of Grand Army Plaza before, amazingly enough. This leg of the line goes south from Eastern Parkway along Nostrand Avenue and are among the final underground IRT trains that would open, in 1920. At the same time, an elevated was built along Livonia Avenue to New Lots Avenue in East New York. If you were a subway buff then, you had new subway lines to check out every few years from 1904 to 1940! After that, construction has slowed to a crawl as costs and maintenance of existing lines have skyrocketed. However, it does appear now that a second leg of the Second Avenue Line from 96th to 125th Streets on the Q train will open sometime in the 2030s.

By 1920, the general mosaics and letterforms used in station signage on IRT and BMT lines had become more or less standardized, with earth tones in brown, green and dark blue employed most often, though Squire Vickers was expanding his palette for several lines on the L and #7 lines.

That kicks things in the head for this walk, but others are upcoming.

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop. As always, “comment…as you see fit.” I earn a small payment when you click on any ad on the site.

8/17/25

16 comments

Shirley MaClaine wouldnt have had a problem with that place if

it had only served women

Krupa Grocery got its name because if is located in what used to be the Krupa Grocery stationery store/newsstand. https://www.yelp.com/biz/krupa-grocery-news-stand-school-supplies-brooklyn When the restaurant took over, it used the same name. There was an article in one of the local papers or a post on an Windsor Terrace Facebook group that said the Krupa family, which ran the newsstand got nothing for the use of their name, not even a discount at the restaurant, though I don’t know if that’s true. It was an old-time luncheonette when I was growing up in the 70s, though I don’t think the counter and rotating padded stools were used for the last 30 years it was open.

I looked up the story in the Brooklyn Public Library’s Brooklyn Newsstand of how Ninth Avenue was renamed “Prospect Park West.” In 1895, residents along the park petitioned for the City of Brooklyn for the renaming they were frustrated that 9th Avenue got confused other 9th Streets and Avenues in Brooklyn and New York, leading to mail being delayed. an ex-alderman and son of a former Brooklyn mayor suggested that it be renamed Talmage Avenue for his father, given that there were already streets named “Prospect Avenue,” a “Prospect Place,” and “Prospect Street” As for the reason why the part beyond the park was renamed, one article said that Father O’Reilly, the rector of Holy Name, said at hearing that residents had no objection to keeping or changing the name as long as it was for the full length from Union Street/Flatbush Avenue to the cemetery. “Prospect Park West” for the full length from Union Street to the cemetery prevailed.

Odd because Park Slope is full of numbered avenues and streets that meet: 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8

The last photo of the Sterling Street station platform shows the new guard railings that the MTA is slowing installing throughout the system. They rare often found at locations where crowding happens, such as at the bottom of the staircase on the #7 platform at the Grand Central stop.

I don’t see these being much help. Still plenty of space for miscreants to push people onto the tracks. You need a wall at the track edge with doors that open when train doors open.

Brooklynites looked over to Manhattan and saw that Manhattanites had a “Central Park West” instead of an “8th Avenue,” so they figured, “WE’LL have ‘Prospect Park West’– we don’t want to look like some backwater town here!”

That’s what I would have guessed.

During the summer you can go to the Smorgasbord in the Breeze Hill section in Prospect Park on Sundays.

https://www.smorgasburg.com/

I lived on PPSW for years. This brought back memories. Thanks! FYI, Tge movies Dog Day Afternoon and Smoke were both shot in PPW stores. (Smoke in its entirety. )

In 1957 our Cub Scout Pack went to a Dodgers game at Ebbets Field. We took the “D” train (now “F”) to 15th Street, and walked through Prospect Park. We were thrilled to meet Johnny Podres strolling with his girlfriend before the game. Brooklyn was a small town in those days!

In the late ’80s I lived near 7th Ave. and 11th St., close to Windsor Terrace. Very little gentrification then, but just starting. The landlord of my building once told me that teenaged Pete Hammill and his brother broke some windows in the front of his building once.

No mention of the now closed Bishop Ford High School which was located in Windsor Terrace..

Use the handy search function, marked by a magnifying glass icon at top of page

https://forgotten-ny.com/2023/02/ex-bishop-ford-windsor-terrace/

The section of Windsor Terrace depicted in the article was developed between 1905 and 1920, largely by developer William M. Calder, who appears to have been sort of the Frederick Trump of his day. Calder was a US Congressman and later a US Senator from NY. He developed the area between Prospect Park and Green-Wood Cemetery from PPW to Terrace Place; this community came to be known as Calderville, but the name seems to have faded from use during the Depression and WWII. (I’ll send info)

Windsor Place was originally known as Braxton Street; paired with Sherman Street they commemorated two signers of the Declaration of Independence whose names city planners just couldn’t fit into Bed-Stuy or Williamsburg. (Carter Braxton and Roger Sherman) Braxton Street became Windsor Place in 1888.

Howard and Fuller Places take their names from William Howard and Junius A. Fuller, partners in the Brooklyn brewing concern, Howard & Fuller.

I grew up at Flatbush and Lincoln Road. You have a picture of my building I think in this post. Prospect Park was my playground, as well as the Brooklyn Botanic Gardens. I remember the Bond bakery and was astounded to learn that my subway stop, which was the D train for most of my life, was the site of the Malbone St wreck. My dad was a big Dodgers fan, and was heartbroken when they left for LA. I remember the derelict houses surrounding it after it closed. We called them the haunted houses. Of course now its all gone and the Ebbets Field houses are there. I remember seeing the Washington Irving bust as a kid and wondering who Irving was. Great memories.

Interesting post, just two minor corrections: I highly doubt that Tiarah Poyau was shot and killed during J’Ouvert (Caribbean Day Parade held on Labor Day) in 1916. I don’t believe that the Caribbean Day Parade goes back quite that far. And, the back of the Bond Bread factory is not at Bedford Avenue and Sterling Street, but at Washington Ave and Sterling St. Carry on!

OK, my error. 2016, thx