In late August 2024 I wandered around Green-Wood Cemetery for the first time in a few years; I have become reluctant to walk in areas without an opportunity to sit, such as park benches, due to back strain (indeed, toward the end of this walk in Industry City I had to squelch a back spasm). I have been in physical training this year, with varying amounts of satisfaction. Part of being 68 years old now, I suppose.

Green-Wood Cemetery, south of Park Slope in Brooklyn, has always been one of my favorite parts of town, as the stillness and quiet are intoxicating. I have given 5 or 6 live tours there, as well as two or three in Uptown Trinity in Manhattan, one in downtown Trinity, and one in the cemeteries in central Queens.

A little background: Green-Wood Cemetery (not “Greenwood”) was founded in 1838 on 478 acres of rolling acreage in what was to be the neighborhoods of Park Slope and Sunset Park. Its first landscape architect was David Bates Douglass, who rode on horseback all over northern Brooklyn with Henry Pierrepont, one of the founders of Brooklyn’s parks system in order to select the optimum area to build Green-Wood.

It was among the first “rural” cemeteries in New York; most burial grounds in the city prior to this had been associated with churches, with the better-off buried under churches in vaults, the rest in churchyards. As the city marched inexorably northward on Manhattan Island, small burial grounds were displaced and no provision was made for the placement of new cemeteries. The solution was to place them in “outer” localities like Brooklyn and Queens. Their wide open spaces made the cemetery-as-park concept possible. In the latter days of the 19th Century and early 20th, cemeteries became parks, with Sunday outings and picnics. Horsecar and railroad routes and schedules became tied to cemeteries’ visiting hours.

Deciding to enter Green-Wood from the south and walk along its south and west sides to its exit on 4th Avenue, I took the F train to Church Avenue and walked north along Dahill Road. Here’s its intersction with Albemarle Road, the first in an alphabetical series of roads with British names. When the Town of Flatbush street grid was conceived and laid out, east west avenues had a simple themeL the alphabet from A to Z: Avenue A, Avenue B and so on. However, when the regions south of Prospect Park were developed, such as the prosaically-named Prospect Park South by Dean Alvord, it was decided to give the streets British names, a time tested method of adding a sophisticated aura. thus, Albemarle Road, Beverly, Clarendon, Dorchester and so on.

The Deco entrance of #70 Dahill Road at 12th Avenue. My father’s companion for the last 20 years of his life, Anna Orlando, resided in this building.

Attached houses on the opposite side of Dahill Road. Though I lived in Bay Ridge, I was quite familiar with this stretch of Dahill Road as a boy, since one parent or the other would take me for weekend rides on the many bus routes emanating from Bay Ridge including the B16, which ran here amid its route along Fort Hamilton Parkway, 13th Avenue and Caton Avenue.

The entrance to Green-Wood on the north side on Fort Hamilton Parkway is flanked by two extraordinary Victorian-era buildings. Richard Upjohn’s massive arch at 5th Avenue and 25th Street gets most of the press, deservedly, but the buildings here, on what can be considered the Cemetery’s rear entrance, are almost as impressive. On the left side of the FHP entrance is the cemetery caretakers’ residence…

… and on the right side is the Visitor’s Lounge. According to the cemetery’s website, “the cottages offered a welcome place to rest after one’s often-long journey to the cemetery, and recall the front parlor of a contemporary brownstone rowhouse.” Both buildings were designed by Richard Upjohn’s son, Richard Mitchell Upjohn, and reflect architectural sensibilities completely lost in the modern era of minimalism.

The Cemetery curates exhibits in the Visitors Lounge. On a previous visit with one of my tours, the Morbid Anatomy Museum, then located on 3rd Avenue in the Gowanus area, had an exhibit that was quite entertaining. In 2024, the exhibit was Adam Tendler’s “Exit Strategy”:

Exit Strategy is a site specific installation in Green-Wood’s Fort Hamilton Gatehouse created by the Cemetery’s 2023-2024 artist in residence, Adam Tendler. Interrogating the complex relationship between grief and personal identity, Tendler creates an immersive environment that meditates on the ways we attach ourselves to memories and physical objects, and the possibilities for letting them go. Layering music, text, visuals, and found objects, this semi-autobiographical work includes notes, voice memos, and personal objects sourced from the local Green-Wood community. At the conclusion of the installation, the accumulated items will be ritualistically discarded as part of a closing ceremony. [Green-Wood Cemetery]

It’s an interesting concept in theory but frankly I was appalled at the presentation, which looked like some of the neighborhood youth had tagged the walls with spray paint. It was incongruous combined with the exquisite stained glass windows.

Meanwhile here are two of the four sculptures depicting the “Ages of Man” by British sculptor John M. Moffitt (1837-1887) carved in brownstone on the lounge exterior walls.

A mature weeping willow tree (appropriate for a cemetery?) greets the visitor at the entrance. In the past, the guard at the front gate gave me some guff for aiming the camera toward the cemetery, but I met with no problems today.

Cemeteries (at least the garden cemetery variety) are built much more for the living than the dead. Green-Wood was conceived of as a restful respite where you would take the family and stroll around, before there were more parks than there are today. Green-Wood has returned to that original premise and even added to it with music performances the last few decades and there are even nighttime tours illuminated by nothing more than the moon and IPhone flashlights. One of the Cemetery’s premier tourguides, Marge Raymond, is a professional singer.

Wealthier “interredees” purchased large monuments, small buildings in fact, to mark their burial plots. Stroll up to the front door and look inside: you will often be rewarded with a stained-glass rendering of a New Testament scene.

At Vine and Fir Avenues, William Florence, born William Jermyn Conlin, was an actor, producer, songwriter, and playwright. A Freemason, he co-founded the Ancient and Arabic Order of the Nobles of the Mystic Shrine, a fraternal organization known as the Shriners. They are currently famed for their Shriners’ Children’s Hospitals for kids with special needs. A poem about the life of William Florence by Staten Islander William Winter, green with copper, is seen on an adjoining plaque.

At Vine and Sassafras Avenue, James Renwick, Jr. (1818-1895) was a prolific architect who designed several of NYC and America’s most famous structures. He was the mastermind behind Grace Church on Broadway and W. 10th Street, St. Patrick’s Cathedral, St. Ann’s Church in Brooklyn Heights, Smithsonian Institution in Washington, Vassar College in Poughkeepsie, as well as the magnificent ruin of Roosevelt Island, the Smallpox Hospital.

Also in the Green-Wood plot, James Renwick Jr.’s father, James Renwick Sr. (1792-1863) was Professor of Natural and Experimental Philosophy at Columbia College, now Columbia University. Renwick Street near the Holland Tunnel was named for Renwick Senior.

Born in Ireland, Civil War Union Brigadier General Thomas Sweeny (1820-1892) moved to America with his family in 1832 and settled in New York City. He joined the Baxter Blues, militia company in 1843, his unit fought in the Mexican War and his right arm was amputated after being wounded.

After he recuperated, he fought against Native Americans in the Southwest and on the Great Plains. When the Civil War began, he was stationed in St. Louis, Missouri and became Brigadier General of Missouri’s volunteers. While fighting at Wilson’s Creek, he was wounded, carried off the field and returned to action in January of 1863. He led troops at Fort Donelson, was wounded at Shiloh, fought at Corinth and led a division in the Atlanta Campaign. After the war, he remained in the Army and retired a Brigadier General of Regulars in May, 1870. [FindaGrave]

Jean-Michel Basquiat (1960-1988), one of the famed modern artists of his time, was the son of Haitian and Puerto Rican parents. Like many young men he became a graffitist or street artist, as well as a guitar player – on one gig he met and befriended Andy Warhol, who became a patron. By age 24, he was selling paintings for $25,000 to the Whitney Museum, MOMA, and other premier venues. His paintings went for auction in the $100,000 range. Basquiat entertained lavishly, but spent money indiscriminately and got hooked on heroin after Warhol passed in 1987, and addiction claimed his life at age 28.

In 1996, he was portrayed in the movies by Jeffrey Wright with David Bowie as Warhol.

Hattie Leah French died at age four, and sister Clara before age two, but they were beloved and their family placed this marble shaft in their memory. “God has plucked our tender buds to blossom with Him in heaven.” Before widespread treatments and vaccinations, disease claimed many very young children.

Captain Marco Cetcovich (1815-1860) a.k.a. John Bennis (he may have taken the name after moving to the USA from Dalmatia, now part of the modern states of Croatia and Montenegro on the eastern shore of the Adriatic Sea).

Though Giuseppe Guidicini (1810-1868) is buried in this plot, the star of the show is his wife Julia, who is featured prominently on the shaft and who predeceased him in 1860. Though the marker is labeled “Guiseppe” it may be a misspelling as Giuseppe is the much more common spelling.

Nearby is a more recent burial, Artie Leib, born Arthur Leibowitz (1942-1991) and wife, Marianne Leib (1944-2018). From the marker decoration, we can infer he was an equestrian or horse enthusiast.

Benjamin Conklin (1800-1859) and his daughter, Ella (d. 1891) are interred here. I had thought an anchor symbolizes a person who worked at sea, but an anchor was often used by stonecarvers to symbolize hope.

As we’ve seen, misspellings on tombstones aren’t uncommon. The inscription reads, “A devoted husband, an indulgant father, faithful Christian.”

Nearby, the Jarvis in this plot was a Freemason, one of the largest and longlasting fraternal and service organizations, as the interlocking compass and square on the shaft imply.

Laura Keene (1826-1873) was an actor and theatre manager. After making her debut in 1848, she managed the Metropolitan and Olympic Theatres in NYC, doing everything from painting scenery, writing scripts and playing leads. She became a top-billed performer.

She was the producer and lead actror in the play “Our American Cousin” and on April 14, 1865 she was appearing in the play at Ford’s Theatre in Washington when she witnessed Abraham Lincoln’s assassination by John Wilkes Booth. She kept the audience calm and tended to the wounded Lincoln backstage. When the president was brought across the street to Peterson House, Keene sat with and comforted Mary Todd Lincoln. Physically, Keene bore a resemblance to modern-day actor Catherine Keener.

Depending on who you speak to, there’s a wide opinion on the accomplishments and career of Dr. James Marion Sims.

Dr. James Marion Sims (1813-1883) is often called the father of gynecology; he founded the Women’s Hospital of New York City. To some, he is a respected figure for having advanced medical knowledge; to others, his name is reviled because in his native South Carolina, he performed experimental surgery on African American women slaves without the benefit of anesthesia. This page gives an account of some of that side of Sims’ story.

Dr. Sims’ statue formerly located on 5th Avenue in Manhattan, sculpted by Ferdinand von Miller III in 1893, was originally placed in Reservoir (now Bryant) Park, was removed from the park in 1928 and put in storage under the Williamsburg Bridge until 1934, when it was then taken to 5th Avenue and 103rd Street on the Central Park side and given a stone pedestal.

In the spring of 2018, Dr. Sims was on the move again. In the wake of some communities’ removal of statues and memorials commemorating prominent Confederate figures, New York City’s Public Design Commission took a look at memorials in NYC that might prove ethically questionable, including the many memorials to Christopher Columbus. In the end, only Sims was deemed worthy of removal. The decision was made to pack his statue off to his gravesite at Green-Wood Cemetery in Brooklyn (the repository of Fredrick MacMonnies’ work, Civic Virtue, also controversial because it depicted a Herculean figure (Virtue) trampling a pair of writhing mermaids symbolizing Vice).

The Guardian article, linked above, states that Sims’ statue was moved to Green-Wood, but I didn’t see it here. If you know where it is, Comments are open.

The “Freedom Lots” on the Cemetery’s south side is one of the largest burial places for African Americans in Green-Wood, with over 1300 interments. Blacks in the 19th and early 20th Centuries were segregated in life and death, and the Cemetery’s less expensive public lots were the only available plots in that era. However some prominent Blacks such as Dr. Susan Smith McKinney and millionaire Jeremiah Hamilton were able to afford private plots.

Marie Delores Eliza Rosanna Gilbert (1824-1861) was born in Limerick Ireland, but was raised in Scotland, educated in Bath, England and Paris, and gained fame as “Lola Montez, the Spanish dancer.”

She first performed in Munich, Germany in a ballet troupe and enchanted King Ludwig of Bavaria, who built her a palace and anointed her Baroness of Rosenthal and Countess of Landesfeldt and made her one of his chief confidantes. A revolt against her influence forced Ludwig to abdicate and Gilbert to return to England and then travel to Spain, where she developed her famed “spider dance” in which she gyrated wildly around the stage, pretending to shake spiders out of her dress, and performed it onstage in North America and Australia. She was a companion of Walt Whitman and Commodore Vanderbilt and became one of the most well-known entertainers in the world.

Gilbert, still using her Lola Montez stage name, became a lecturer and spiritualist beginning in 1856, touring Europe. She devoted the last years of her life to helping “outcast women.” Never a great money manager, she died in poverty. Her monument at Green-wood uses a condensed version of her actual name and doesn’t mention her career as Lola Montez, the Spanish dancer.

Montez was portrayed in a 1955 movie musical by Martine Carol; the cast also included Peter Ustinov, and by Yvonne DeCarlo in the 1948 movie “Black Bart.” In “Ride to Hangman’s Tree,” a loose adaptation of “Black Bart” in 1967, Melodie Johnson played a Montez-esque dancer, Lily Malone, with considerably more leg. Johnson, now a famed mystery writer, is one of my few celebrity follows on twitter (sorry — x).

Some of the newer occupied plots in Green-Wood are occupied by Asian American interments.

Adlenia M. Mortan Gordon’s tomb is located on a hillside. In the background we can see the gravesite of a famed inventor and painter.

Samuel Finley Breese Morse, the inventor of the telegraph, began his career as a prominent portrait painter (including John Adams and James Monroe) and was elected first president of the National Academy of Design in 1826. But he became more and more interested in science and its practical uses. In 1839 he learned photography from its own inventor, France’s Louis Daguerre, and introduced the process in the United States.

In 1825 Morse was commissioned to paint the portrait of the Marquis de Lafayette in Washington. A messenger delivered a note from his father, notifying him that his wife was quite ill. He immediately left for his home in New Haven but by the time he reached home, his wife had passed away and was already buried. He was inspired to think of methods of immediate long-distance communication.

Consulting with scientists he knew who worked with electromagnetism, including Charles Jackson of Boston, Morse developed an experimental single-wire telegraph by 1835, with the first practical telegraphy system launched in 1844 between Washington and Baltimore along a series of telegraph poles (underground construction was impractical at the time). The first message, sent in the Morse code that he also devised in “dots and dashes” , read: “What hath God wrought!”

In 1845, Morse hired Andrew Jackson’s former postmaster general, Amos Kendall, as his agent in locating potential buyers of the telegraph. Kendall realized the value of the device, and had little trouble convincing others of its potential for profit. By the spring he had attracted a small group of investors. They subscribed $15,000 and formed the Magnetic Telegraph Company. Many new telegraph companies were formed as Morse sold licenses wherever he could. The first commercial telegraph line was completed between Washington, DC, and New York City in the spring of 1846 by the Magnetic Telegraph Company.

On the down side, Morse in his time was known for his anti-Catholic and Nativist sentiments and his support of slavery.

William Magear “Boss” Tweed (1823-1878) was born at #1 Cherry Street in lower Manhattan (an address that is no longer there) and left home at age 11. He worked in a variety of occupations until joining state assemblyman John J. Reilly in founding volunteer fire brigade Engine Company #6 in 1848. He was elected to the House of Representatives in 1852 and rose to the executive committee of Tammany Hall in 1858, and became “Boss” Tweed when he was named Grand Sachem of the political organization in 1863. He became a master at skimming large sums of money off city projects for personal use. He had amassed a fortune of $12 million by 1870.

Tweed actually accounted for many good works in the city – he built hospitals and orphanages and widened and straightened Broadway in the Upper West Side. He secured land from Central Park upon which was built the Metropolitan Museum of Art. However, the “Tweed ring” stole $200 million from the city during his career and the city deficit ballooned from $36M to $130M by 1870. The Tweed Courthouse standing near City Hall cost taxpayers in excess of $200M in today’s money. Expenses were way overbilled, and the overage went into the accounts of Tweed ring members. Tweed and his cronies stole what amounts to today’s $3.5 billion.

After he was arrested and held for trial, he was released to spend time with his family in 1874. He fled to Spain, but was arrested by a Spanish customs official who recognized him from Thomas Nast’s caricatures that had appeared in the newspapers. He was returned to the USA and died in the Ludlow Street Jail in 1878.

There’s a new addition adjacent to the Tweed plot: Park Sloper and journalist Pete Hamill (1935-2020), who knew NYC, and especially Brooklyn, inside and out. Hamill seems to be eyeing Tweed warily, from beyond the grave.

“Pete is buried in Green-Wood Cemetery, a place he loved, which he always called “the Green-Wood,” as if it were a Bay Ridge bar. As a kid, in the twilight, Pete and his pals would climb the Green-Wood fence at the end of 7th Avenue, eight blocks away from his railroad flat on Pete Hamill Way. Inevitably they would cower in the darkness wondering what specters might emerge beyond the next tombstone. Pete always claimed those imaginings set him on the course to becoming a writer.

70 years later he and Fukiko bought a family plot there after a tour revealed a vacancy near the gaudy gravestone for Boss Tweed. Hamill thought the famously corrupt politician would make for a terrific after-life companion. And good copy. For Pete, it was always about the stories he could tell.” [Joe Enright]

I never met Pete Hamill, but I did meet his brother, Denis, who interviewed me when the Forgotten Book came out in 2006.

I happened upon the marker for DeWitt Clinton Falls (1828-1892). His namesake, DeWitt Clinton, was a founding father who served as NY State Assemblyman, NYS Senator, NYS Governor, US Senator and NYC Mayor during an illustrious career capped by his indefatigable support for the Erie Canal. Several streets around town were named for him, as well as a scattering of forts, schools and other structures. After Green-Wood Cemetery opened in 1838 his remains were exhumed from the original burial plot in Albany, NY and moved to Brooklyn in 1850. Three years later, Henry Kirke Browne’s monumental bronze statue of Clinton was placed at his burial site. It appears on the cover of New York Illustrated number for June of that year.

General DeWitt Clinton Falls, Jr. (1864-1937), also interred in Green-Wood, was a renowned military historian.

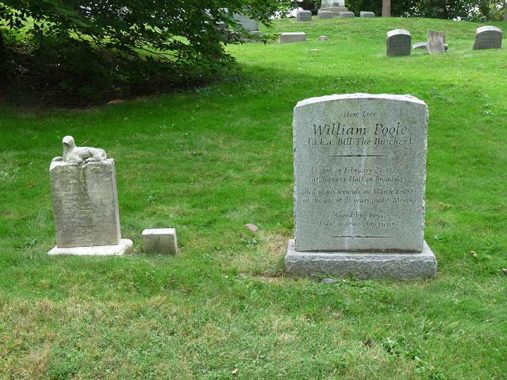

When my Green-Wood tours have passed the burial place of “Bill the Butcher” William Poole, I have always had to edit my remarks rather than take up too much time, but I’ll present them in full here:

A small, unobtrusive granite headstone containing the name William Poole (1821-1855) was placed in Green-Wood on February 13th, 2003. A butcher by trade, Poole’s true profession was as an enforcer for the Know-Nothing Party. He grew up as a member of the Bowery Boys, a violent street gang. Poole, effective with fists, knives or firearms, would routinely bite off opponent’s ears or cut out opponents’ eyes, testicles and other body parts in fights. He was deadly knife fighter; his nickname “The Butcher” was not bestowed primarily for his legitimate profession.

Poole fell in with the Know-Nothings since their philosophy matched his own: they were ineluctably opposed to Irish Catholic immigration, as the newcomers were in competition for “native-born” Americans’ jobs and they were opposed to those political parties vying for immigrants’ votes. The Nativist movement became a political force in mid-1800s America. Poole joined Captain Isaiah Rynders’ political organization, the Americus Club.

On February 24, 1855 Poole lost his last fight. Tammany regular John Morrissey was at Stanwix Hall, a Broadway billiards establishment, with some friends. Poole walked in. Immediately, Morrissey strode up to Poole, pointed his revolver at his temple and squeezed the trigger. The gun misfired, whereupon Poole pulled his own pistol. One of Morrissey’s friends noted that it might be dishonorable for Poole to shoot an unarmed man. Poole picked up two carving knives and challenged Morrissey to a fight, but policemen broke up the conflict before it could get started. Morrissey went home for the night but his companions, Lew Baker and Pawdeen McLaughlin, armed themselves and returned to Stanwix to find Poole, similarly armed.

Accounts vary about who fired first, but Poole wound up getting hit in the leg; when he went down, Baker drilled him in the heart and abdomen. Poole, amazingly, was able to fire a knife at Baker as he fled the Stanwix. Poole was able to survive with his wounds for two weeks, which gave him time to rehearse his supposed final words: “Good-bye boys, I die a true American.”

The Nativists gave Poole a lavish funeral, as thousands lined Broadway and over 5000 gang members marched in solemn procession behind his flag-draped coffin. He was entombed in a family plot in Green-Wood. Morrissey went on to get elected to two terms in the House of Representatives after he had amassed a fortune of nearly a million dollars from extortion rackets and gambling dens.

Martin Scorsese’s 2002 epic, “Gangs of New York,” takes artistic license in depicting Daniel Day Lewis’ Butcher, renamed William Cutting, as participating in the 1863 New York City Draft Riots (he had died 8 years before), but seems to have nailed Poole’s violent and corrupt temperament accurately. His stone in Green-Wood, erected, one would think, to take advantage of the film’s popularity, quotes Poole’s alleged final pronouncement.

[Poole biographical info from William Bryk’s “Old Smoke” column in NY Press]

This view from the Cemetery of Brooklyn’s Industry City and the Manhattan skyline beyond reminds me of the final montage in “Gangs of New York” of the skyline evolving through the decades.

While an achor can represent the abstract concept of hope, Captain William Parsons (1813-1867) was a seaman who died on duty in Hamburg, Germany. His shaft is decorated with an anchor, capstan and ropes.

William Augustus Spencer (1855-1912) was born into a large, fabulously wealthy family. He had two brothers and four sisters. One of his sisters famously married into Italian royalty, becoming Princess di Vicovaro Cenci. His brother Lorillard was a publisher who founded the well-known Illustrated American Magazine. The family split their time between houses in Switzerland, Paris, and New York.

By the way, one of the houses their family owned was Halidon Hall, in Newport, Rhode Island. This is not only an interesting example of Gothic Revival architecture, but it was later home to “The Cowsills” [sic] –a corny singing family act that had a string of #1 hits in the 1960s. They were the original inspiration for the also-corny TV show, The Patridge Family. They often featured Halidon Hall on their record covers. [Lost to Sight]

Tragically, Spencer was one of the many who went down with the Titanic in April 1912.

[No Cowsills song went to #1, though “The Rain, the Park and Other Things” hit #2 Billboard and #1 in Canada.]

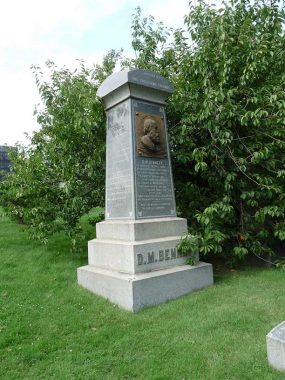

DeRobigne Bennett (1818-1882), preceded Richard Dawkins and Madalyn Murray O’Hair as perhaps the most prominent anti-religionist in the public imagination, publishing The Truthseeker as well as several books describing his anti-church leanings. After his death, the Pittsburgh Daily Post, learning that several of his writings were to appear on the shaft marking his plot in Green-Wood, mounted a public campaign against it, to no avail. The monument also is decorated with a quill pen laying atop a sword.

Instead of exiting via the Upjohn main gate at 25th Street, I instead followed the 4th Avenue exit under a handsome masonry bridge at 5th Avenue. The path follows a colonial-era road called Martense Lane, after an early Dutch Kings County family.

Before getting on the train I noted this interesting building, formerly the Rugge Construction Co. on 36th Street between 3rd and 4th Avenue. If the area ever gentrifies, it’ll likely take on a different appearance.

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop. As always, “comment…as you see fit.” I earn a small payment when you click on any ad on the site.

9/14/25

7 comments

Your excellent post prompted me to educate myself that Boss Tweed was not William “Marcy” Tweed. Perhaps I should not rely on Dustin Hoffman in “Marathon Man” for my NYC history facts.

Basquiat died at age 27. Yes, he was a member of the 27 Club.

“Poole, amazingly, was able to fire a knife at Baker as he fled the Stanwix.”

I find it amazing that a knife could fire…unless it was a knife pistol or a gun knife… 🙂

Nitpickers will pick nits. “Fire” means to quickly throw.

See definition 3B in Marriam-Webster:

fire

2 of 3

verb

fired; firing

transitive verb

1

a

: to set on fire : kindle

also : ignite

fire a rocket engine

b

(1)

: to give life or spirit to : inspire

the description fired his imagination

(2)

: to fill with passion or enthusiasm —often used with up

c

: to light up as if by fire

d

: to cause to start operating —usually used with up

fired up the engine

2

a

: to drive out or away by or as if by fire

b

: to dismiss from a position

3

a

(1)

: to cause to explode : detonate

(2)

: to propel from or as if from a gun : discharge, launch

fire a rocket

(3)

: shoot sense 1b

fire a gun

(4)

: to score (a number) in a game or contest

b

: to throw with speed or force

fired the ball to first base

fire a left jab

c

: to utter with force and rapidity

4

: to apply fire or fuel to: such as

a

: to process by applying heat

fire pottery

b

: to feed or serve the fire of

fire a boiler

Such wonderful history in Green-Wood! And I knew exactly what you meant by firing a knife…

Love this pictorial essay. Thank you for posting. It takes me back to 2010 when Open House NY

(are they still around? I hope so!) hosted the event, “Angels and Accordions” at Green-Wood Cemetery –

a truly ethereal affair: dancers dressed… well, angelically, accompanied by accordionists, posing and

performing on gravesites and memorials as our tour group ambled by on that crisp, clear Autumn afternoon.

I can’t remember what I had for breakfast this morning but I’ll never forget that entire day.

Unfortunately it’s no longer performed; not since 2010 🙁

https://www.green-wood.com/2009/angels-and-accordions-2/

https://www.flickr.com/photos/ennuipoet/5066710944/in/photostream/

I used to be an enthusiastic open Houser, but the crowds got too big, the waits too long, and too much admission charges.