I last traipsed around Inwood back in 2019, the same year FNY did a very successful tour of Inwood and its neighbor across the Harlem River, Marble Hill. Inwood was the last part of Manhattan to develop along the lines of neighborhoods to the south. During the Revolutionary War, colonials erected Fort Cox, or Fort Cocks, overlooking the Hudson River. After independence was attained, for the next century and a half, Inwood Hill Park was occupied by a variety of country mansions including the home of department store magnate Isidor Straus and his wife Ida, who lost their lives in the Titanic disaster. Inwood’s original name was Tubby Hook, which is preserved in a Broadway bar.

A system of winding roads traversed the hilly ground in this northernmost Manhattan Island enclave. Some of them now describe park paths in the vast Inwood Hill Park. The City took title to this territory in 1916 and gradually, for the next 25 years, Inwood Hill Park as we know it was developed. The park includes a salt marsh and ‘virgin’ forest left over from the pre-colonial period. Except for some historic farm remnants, Inwood was mostly developed in the first 2 decades of the 20th Century. While some areas around town are stingy with parks, Inwood has three: Inwood Hill Park, Isham Park and on its southwest end, Fort Tryon Park.

Inwood’s easternmost section bordering the elevated #1 train is given over to auto body shops and car washes, while apartment buildings, some Deco, are found further west. And, there are some freestanding homes, a rarity in Manhattan, which have their own Landmarks Preservation Commission designation, as we’ll see.

Alighting at the #1 207th Street station, the northernmost on Manhattan Island, which affords a view of the 207th Street Subway Yard. It not only services Broadway/7th Avenue IRT trains, but also the IND 8th Avenue line (A train), which has an underground track connection.

As you can see by the staircase, the IRT el stations have unique railings and covered staircase exits. Out of the picture is the Swiss chalet-type stationhouse.

I was glad to see Famous Jimbo’s Hamburger Palace at 10th Avenue and West 207th is still in business. Years ago I was pleasantly surprised at the quality of the fare and on one of these Inwood forays, I’ll stop by when I don’t already have dinner planned. This is one of a few Jimbo’s scattered around town.

Floridita, 3856 10th Avenue, offering fusion Cuban/Dominican fare, opened in 1995 but that classic sidewalk sign seems like it’s from a previous age.

The el turns away from 10th Avenue and onto Nagle Avenue at West 205th. This unusual entrance at #278 Nagle opens up into an inner courtyard.

A classic curved mast with bracket streetlamp is preserved at Nagle and Academy Street. It has supported incandescent, sodium and LED lamps during its over 70 year career. When “octagonal pole” lamps first appeared in 1950, they were all curved masts, but they were quickly overtaken by straight masts and then by “cobra necks.” I’d say there are a few dozen surviving curved masts scattered around town, many surviving underneath elevated trains.

I had never walked Academy and Cooper Streets, so that was my quest today. Academy Street is one of the few streets named for a public school, the original PS 52, which I will discuss a bit later.

Apologies, as the sun’s lower position in the sky from October-February can play havoc with photography from some angles. Street artist Snoeman‘s celebration of Dyckman Street can be found nevertheless on Academy Street. The mysterious Snoeman has been brightening up local bodegas beginning at the outset of the pandemic in 2020.

With exceptions which will be noted, Inwood is a territory of large multifamily buildings. It was City of Yes decades before the concept was considered. This grouping of Tudor-style buildings lines all of the north side of Academy Street between Nagle and Post Avenues.

Early versions of FDNY fire alarms had shafts at the top, to which were attached incandescent bulbs in red glass casing. Later, the red glass casing was switched to orange plastic. The other shot has the NYC tradition of sneakers tossed onto a wire.

More apartment building stylings at Sherman Avenue. The new facade belongs to the Equity Project Charter School. Sherman Avenue is not named for Civil War General William Tecumseh Sherman, but for a prominent local family in Tubby Hook’s early days.

The imposing Intermediate School 54 (The Harold O. Levy School) was built in the 1920s on Academy Street between Vermilyea Avenue and Broadway, but it wasn’t the academy Academy Street was named for. That honor was for the very first public school in Inwood, built on Broadway and Academy Street in 1858 as Ward School 52, when the area was sparsely settled. The two schools stood side by side until 1956, when the original was torn down two years before its centennial.

This post on My Inwood gives not only the hsiory of the school but also the general area.

One of these is not like the others. #4857 Broadway, known as The Stack, was built in 2013. Surprisingly behind the FedEx truck is an empty lot which has been empty as far back as Street View goes, 2007. “It holds the distinction of being Manhattan’s first Pre-Fabricated Modular building. Designed by Gluck+” Rentals in Inwood are still in the $2000/m range, cheap for Manhattan.

The historical centerpiece of Inwood is the Dyckman Farmhouse at Broadway and West 204th Street, which has been here since about 1785 and is Manhattan’s last remaining Colonial farmhouse. It was built by William Dyckman, grandson of Jan Dyckman, who first arrived in the area from Holland in the 1600s. During the Revolutionary War the British took over the original Jan Dyckman farmhouse; when they withdrew at the war’s end in 1783 they burned it down, perhaps out of spite.

The farmhouse was rebuilt the next year, and the front and back porches were added about 1825; the Dyckman family sold the house in the 1870s and it served a number of purposes, among them roadside lodging. The house was again threatened with demolition in 1915, but it was purchased by Dyckman descendants and appointed with period objects and heirlooms. It is currently run by New York City Parks Department and the Historic House Trust as a museum. A copy of one of the occupying Hessian soldiers’ log huts, with a log roof, can be found at the back of the house.

FNY’s Inwood tour swung by in July 2019.

According to both Henry Moscow’s The Street Book and Sanna Feirsein’s Naming New York, Cooper Street was named for author James Fenimore Cooper of Leatherstocking Tales fame. I question this, as Cooper wasn’t a northern Manhattan resident. In any case it’s lined with apartments, some of which are exquisite Deco examples.

A large schist rock outcropping can be found on Cooper Street that serves as the foundation for a group of attached residences on the corner of West 207th Street. The schist was dragged there by a glacier in prehistoric times, and surveyors decided to leave most of them in place rather than dynamiting them when laying out streets.

I liked some of the signage at West 207th and Cooper, some of which uses the Souvenir font that screams “1970s”.

What could be one of the two last gaslight posts on public Manhattan streets can be found here, at Broadway and West 211th Street. The other one is on Patchin Place in Greenwich Village. However, old photos reveal that these posts, in addition to holding gaslight fixtures, could also carry street signs and mailboxes. The only older photos I have reveal street signs on this post. However, gaslamps have not been commonly used on NYC streets since the early 1910s, so this pole may have originally carried a gaslamp and later, street signage. I always check on this artifact when in the area, as it can easily be toppled by an errant vehicle.

I liked the sign for Grandpa’s Brick Oven Pizza, Broadway east of Isham Street, which features Clarendon Bold Condensed.

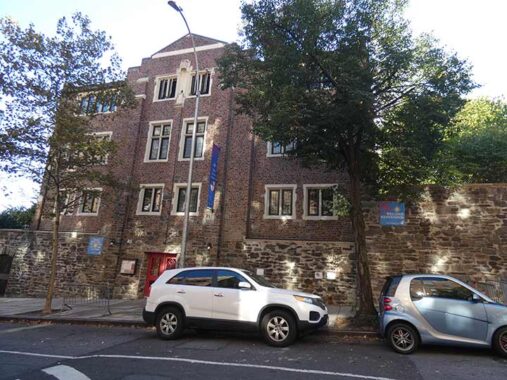

The first Good Shepherd Catholic church, Broadway and Isham Street, was a wood frame building that was moved across Cooper Street around 1930 and later razed to make way for an addition to the elementary school.

When the IND subway reached Inwood in the early 1930s, the population increased, necessitating a bigger church, and the present Romanesque church was built on Broadway and Isham Street in 1935 from Fordham gneiss mined in Manhattan and Bronx quarries. Originally established to minister to Inwood’s Irish community, the Church of the Good Shepherd of today with the aid of the Capuchin Franciscan Friars, Province of St. Mary serves a largely Hispanic congregation.

On the Isham Street side of the church you will find a 9/11/01 memorial garden featuring iron beams salvaged from the site of the terrorist attack, and a display of the names and photographs of Inwood residents killed tat day and its aftermath.

Like other parks in northern Manhattan, the site of Isham Park played a crucial role in the battle of Fort Washington during the American Revolution. The site served as a landing point for Hessian troops coming up the Harlem River to drive the American forces to Westchester and New Jersey.

In 1864 William B. Isham (puzzlingly, pronounced “EYE-sham”), a wealthy leather merchant, purchased twenty-four acres along the Kingsbridge Road, now known as Broadway, from 211th Street to 214th Street, and northwest to Spuyten Duyvil Creek.

The park originally included the old Isham mansion, stables, and green house, with the mansion located at the summit of the hill. The park attained its present size in 1927 after Isham family donations and other land purchases. The mansion was razed in 1940.

The Boston Post Road, which followed an already established Native American trail, was established in 1673 as couriers bringing mail to different locales in the colonies traveled the trail, which was then very rough and interrupted in several locations.

After nearly a century, the road was straightened and improved somewhat between New York and Boston, and from 1753-1769 heavy stone markers were set at one-mile intervals, with the surveying supervised by Benjamin Franklin. Postal rates were set by the distances between one spot and the other. Did “Poor Richard” handle this 12-mile marker, now embedded in the Isham Park wall? Perhaps he did.

Pictured is Park Terrace West, a road that follows a curved path around a hill, cutting through the park itself.

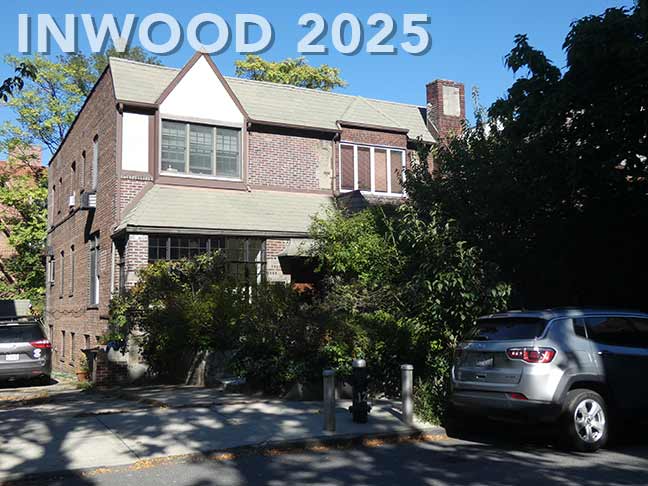

Speaking of Park Terrace West, here at West 217th you’ll find a grouping of standalone private residences, now a rarity in Manhattan except for historic colonial-era buildings such as Morris-Jumel Mansion. They were built by the same developer and in 2018 were given Landmarks Preservation Commission designation:

The Park Terrace West-West 217th Street Historic District is comprised of 15 two-story houses, all either free-standing or semi-detached, with yards and garages, more commonly found in the city’s other boroughs. The small scale of the houses and the suburban quality of the district is due to the later development of this part of Inwood, which was occupied by large estate properties or farms that were not sold until the 20th century.

Designed by architects Moore & Landsiedel, Benjamin Driesler, Louis Kurtz, C. G. de Neergaard, and A. H. Zacharius between 1920 and 1935, the district illustrates the popularity of the eclectic revival styles and the influence of the Arts and Crafts in American residential architecture during the 1920s and 30s. Although six different architects or firms used two distinct revival styles: Tudor and Colonial Revival, the area presents a collection of houses unified by their scale, similar architectural styles, and use of landscaped gardens that accentuate the area’s topography. The houses are remarkably well-preserved and retain most of their original design and materials. [LPC]

I have been more diligent about noting honorific signs. Joseph Kellett was an Inwood resident who perished on 9/11/01.

Seen here are the two stadiums in Columbia University’s Baker Athletics Complex at Manhattan Island’s northern end at West 218th Street, the Rocco Commisso Soccer Stadium and Robert K. Kraft Field at Lawrence A. Wien Stadium (football). (Kraft, a Columbia graduate in 1963, owns the New England Patriots, whom the Giants defeated in the Super Bowl. The Jets? The less said the better.)

I have had two very tentative connections with Columbia. In 1978, alma mater St. Francis College had an important playoff game at the Baker complex, which I attended (they won), while in 2010, I gave a Powerpoint chat about Forgotten New York at Fayerweather Hall (or was in Avery? I forget now) on the Columbia campus.

A pair of honorific signs: Inwood resident Brian Patrick Monaghan was a 21 year old carpenter, on his second day on the job, at the World Trade Center on 9/11/01; Homer Young Kennedy was a longtime caretaker of Inwood Hill Park.

Indian Road, which borders Inwood Hill Park and grants the apartment houses lining it a great view of the Hudson, doesn’t show up on maps (at least the ones I have access to) until the 1920s. The road is so named because relics and artifacts by the Rechgawawanc and Weekweskeek Indians, associated with the Lenape, were discovered during excavations in the area, and the road is believed to follow an ancient trail. Rather amazingly, Indian Road is the only thoroughfare on the island of Manhattan named “Road.” Another “Road,” River Road, is on Roosevelt Island.

Inwood Farm, at Indian Road and West 218th, was called Indian Road (the restaurant) on summer 2012 when an FNY tour stopped in around 3 PM. That was our mistake, because in a scenario I have seen repeated around town, we were told it was between meals and the dinner menu wasn’t available till after 4 PM, and we had to settle for what they had left over from brunch. Subsequently, I’ve steered tours into diners after tours when feasible, where food is available around the clock. Typically we are hungry as jackals after marching for 3-4 hours! No food? Jeez….

|

|

|

|

|

The blue and white 60-foot by 60-foot Columbia University “C” has been painted and repainted on the rock facing the Harlem River since 1952. It was originally conceived by Robert Prendergast, a medical student of Columbia University and coxswain on the heavyweight rowing crew team. Prendergast approached the New York Central Railroad for permission (which was given) to have this sign painted on the 100-foot-high wall of Fordham gneiss, which was completed in the fall of 1952 by the rowers of the crew team, which continues to maintain it.

The building above it is the huge “Blue Building,” #2400 Johnson Avenue in Spuyten Duyvil, built in 1969.

Inwood Hill Park, in the area surrounding NYC’s only salt marsh facing the Harlem River, proved irrestistible to the FNY camera. As natural as some parts of Central Park look, every square inch of Central Park was originated on the planning boards of planners Frederick Olmsted and Calvert Vaux. Inwood Hill Park is 196 acres of primordial forest (with the occasional path and rusting park lamppost). It was the site of Native American habitation; deer and raccoon were hunted for food and clothing. After the Civil War, prominent families built large mansions here overlooking the Hudson, among them Isidor Straus, who perished aboard the Titanic in 1912, and the Lord family of Lord & Taylor. The area officially became a park in 1926.

Inwood Hill Park contains the last remnant of the tidal marshes that once surrounded Manhattan Island. The marsh receives a mixture of freshwater flowing from the upper Hudson River and saltwater from the ocean’s tides. The mix of salt and fresh waters, called brackish water, has created an environment unique in the city and the marsh contains wildlife such as fiddler crab and ribbed mussel developed a dependent relationship with the cordgrass that colonized it.

One of these days I may explore the remainder of the park in the “wild” sections, where pak paths follow former roads that connected estates, but the steep-ish hills are a challenge for my lower back. I’m told there are some surprises to be found in addition to the small caves the Native Americans inhabited.

The arched Henry Hudson Bridge, opened in 1936 to bring the Henry Hudson Parkway across the Harlem River, can be seen from the park.

The remainder of the walk was along busy Seaman Avenue, Inwood’s main north-south conduit other than Broadway. Seaman Avenue is anmed for John and Valentine Seaman, who owned an estate in the area in the 1800s. A large masonry arch that was placed at the front gate remains in place at Broadway and West 215th Street.

Isham Avenue is subnamed for major league baseball’s Matty Alou (1938-2011), a National League batting champion from the Dominican Republic. Though he never resided in New York City, Dominicans in Washington Heights and Inwood point with pride to his accomplishments. He was one of three brothers who had lengthy careers in Major League Baseball, with Felipe and Jesus Alou. All three broke in with the San Francisco Giants and appeared in the outfield together three times.

Matty Alou was a spare outfielder and occasional starter with the Giants until he was traded to the Pittsburgh Pirates in 1966, and he went on to lead the National League in batting with a .342 mark his first season with the team. He played for the New York Yankees in 1973, joining Felipe, who played for the Bombers from 1971-1973. Jesus, meanwhile, was a New York Met in 1975. Felipe went on to become a successful manager with the Montreal Expos, where he had the club in first place in 1994 only to see the season cancelled by a strike.

Matty Alou was rewarded with an honorary street renaming at Isham Street and Seaman Avenue in 2015, four years after his death.

If you’re looking for a successful major league player from northern Manhattan, look no further than Manny Ramirez, who immigrated from the Dominican with his family at age 13. It’s possible that his success with the Boston Red Sox precludes him from being honored on a New York City street sign. Also: see Comments

A sampler of some of Seaman Avenue’s residential architecture, some of it prime Art Deco.

One-block Cumming Street runs between seaman Avenue and Broadway north of Dyckman and named, presumably, for a local property owner. For such a short street, there’s plenty of interesting architecture including the apartment complex #25 Cumming and at the east end of the street at Broadway, the Joseph and Sheila Rosenblatt Building, which contains Inwood’s public library and affordable housing.

Can a church blend in with its surroundings? Inwood’s branch of Holy Trinity Episcopal Church seems to try. It was constructed in the 1930s, with only the lower portion completed as the Depression cancelled grander plans.

Wherever I go, I get “supermarket envy.” Little Neck had the world’s smallest Stop ‘N Shop, which gave way to a J Mart. I don’t prefer Asian food, so I use Amazon Fresh for my groceries since the pandemic.

Plenty of jokes have been heard about the intersection of Seaman Avenue nd Cumming Street. Forgive me, but I get more of a chuckle from the name of the Broadyke Apartments at Broadway and Dyckman (get it?). The IND A train reached these parts in the 1930s, and the building looks older than that: thus, the subway entrance must have been built after it had already been open for a few years.

With that, I’d better get on the train before I get myself in any more trouble.

Check out the ForgottenBook, take a look at the gift shop. As always, “comment…as you see fit.” I earn a small payment when you click on any ad on the site.

10/26/25

16 comments

Great posting, but needs some minor fixes. The #1 station at 207th Street is not Manhattan’s northernmost subway station; that honor is two stations to the north, at 225th and Broadway, just north of the bridge the spans the Harlem River Ship Canal. Although the station appears to be in The Bronx, it is still in Manhattan, And that allows me to segue to a much older FNY posting, about how the blocks around that #1 at 225th and Broadway are called Marble Hill and are politically part of Manhattan, even though the land has been physically tied to the Bronx for over a century. Here’s a link to that posting, which goes into the full history of how Marble Hill was “sawed off” from Manhattan. https://forgotten-ny.com/2011/10/marble-hill/

Finally, on the subject of baseball, there are at least two other major league ballplayers from northern Manhattan. One is Lou Gehrig, born in Yorkville near 2nd Avenue and 94th Street and raised in Washington Heights. The second one is Rod Carew, born in Panama and immigrated to Washington Heights as a teenager. Both Gehrig and Carew are, of course, Hall of Famers.

You are absolutely correct about the 225th Street 1 train stop being the northernmost Manhattan (Borough of New York) station, given its being located south of the now filled in Spuyten Duyvil Creek. .Nevertheless, I do want to give the station at 215th Street its due as the furthest north on the ISLAND of Manhattan. Prior to the recent frenzy of building taller and bigger apartment buildings, one was able to stand on the southbound platform and see the Empire State Building off in the distance while you waited for the train.

Kevin, this link to Cole Thompson’s Myinwwod.net discusses all the named streets in Inwood. It looks like you may have consulted it for this post. I only bring it up since it mentions that 204th Street was originally named Hawthorne Street, which gives some weight to Cooper Street being named for James Fennimore and not some local figure. Interestingly, W. 207th Street was once named Emerson Street, but it was not a literary reference. It was “named for the Reverend Brown Emerson of the Mount Washington Presbyterian Church” according to the same post by Thompson.

The old hand drawn Hagstrom had a dead end Emerson Street at Seaman and West 207. However the playground there is named Emerson.

Since late 1972, I have lived on Seaman Ave, about a block and a half south of Emerson playground. Born in 1995, my daughter played there once she was big enough to enjoy being taken to a playground. It was very old school with most of the now forbidden equipment. It got a total make-over maybe 25 years ago and rubber mats and a sprinkler fountain made their appearance. By then we had moved on to a newly constructed playground near the intersection of W 214th Street and Indian Road.

I had lived here for decades, seeing reference to Hawthorne, Cooper and Emerson on streets and buildings, until the light bulb went on regarding the potential literary connection.

Sneakers hanging from a wire can be seen in many cities. They signify that narcotics are for sale in the area.

Urban legend, as a retired cop, sneakers hanging from a wire don’t signify the availability of narcotics, its just the result of kids having stupid fun.

Urban Myth. I take a daily 10 mile ride on my bicycle and see this in areas where there are no buildings or places for narcotic sales. Some kids and young adults find it challenging to get the sneakers, boots etc. over the wires.

WRONG, it was something we kids did to celebrate the last day of (elementary) school. Drugs had nothing to do with it.

Great overview! Sorry we missed you. We live on Seaman, and you hit so many of our usual haunts.

Great article Kevin, as usual. One small note, the schist at 207th Street was not “dragged there by a glacier.” It was formed in place by intense heat and pressure as a result of two tectonic plates colliding about 450 million years ago. A metamorphic rock, the Manhattan schist provides the sturdy foundation layer for the tall skyscrapers in lower and midtown Manhattan. It can also famously be found in Isham and Central Park. The furrowed and smooth surfaces of Umpire Rock adjacent to Heckscher Playground are an outstanding example of glacially polished Manhattan schist.

I was with you for the 2012 Forgotten tour of Inwood. I remember us all having a nice meal at the Indian Road Cafe. I didn’t realize we were in between servings. A few of us stayed late into the evening. Wonderful time!

Likely everyone reading this column knows that part of Manhattan (i.e., Marble Hill) is presently attached the mainland. Fewer know that part of the Bronx is presently attached to Manhattan Island and is part of Inwood. That small peninsula upon which the Inwood Hill Nature Center is sited had been part of the mainland. When the Harlem River Ship Canal was built, it not only cut off the tip of Manhattan Island but it also cut off a tip of the Bronx. The original path of Spuyten Duyvil Creek includes the present-day lagoon just south of the nature center. It is not entirely clear if the legislation was legally adequate to remove this remnant point from both the borough of the Bronx and Bronx County and annex it to the borough of Manhattan and New York County (the necessity for clarity is minimal because, unlike Marble Hill, no one lives here). But what is generally now considered to be part of Inwood was clearly once part of the Bronx and connected to the mainland.

Yes. I have looked at many photographs and maps from before the Corps of Engineers created the present channel and have seen what you describe. I have been trying to determine exactly where the Johnson Iron Works was located. It was definitely somewhere on ground that was severed from the Bronx, but I can’t tell if it was as far south as where the current picnic area and nature center are located.

This list of street lighting types appeared in “ Transactions of the New York Electrical Society” article “ The Street Lighting of the City Of New York: It’s Development and Present Condition” , March 1913.

19,180 Enclosed Arc Lamps

17,991 Incandescent Lamps

44,653 Single Mantle Gas Lamps

1816 Naptha Vapor (Gasolene) Lamps (used in “frontier areas” where neither electricity or gas was available).

The end of the article states that” By far the greater territory in our City will be covered for a long time to come with our old standbys: the standard enclosed carbon arc lamp and the mantle gas lamp”.

It was ironic that 1913 was the year that saw one of the most significant improvements in the tungsten lamp, the use of an inert gas fill rather than a vacuum. This increased both the light output and doubled the life of the lamp.

Less than 16 years later, an article appeared in the Times entitled” New York’s Lights Now Robotized”. It mentioned that the last two ( out of group that used to number over 500 ) gas lamplighters had been let go. Almost all of the street lights in Manhattan were now turned on and off via a “pilot” wire from the local New York Edison substation. The exceptions were Central Park, where the lights were controlled by individual time switches that were wound up once a week, and lights on the lower east side turned on and off individually by “youthful keymen”.

Seeing those houses almost made me think you took a quick detour into Marble Hill, which was the only Manhattan neighborhood I know that has these.