There’s a lot of Forgotten stuff the guidebooks want nothing to do with right under the noses of Wall Street brokers and Statue of Liberty-bound Iowans right down at the tip of Manhattan Island. We hadn’t done a Manhattan Forgottentour south of 34th Street so it was time for a Lower Manhattan march.

A crowd of 60 (I always overbook) was whittled in half with dire forcasts of approaching fronts, and your webmaster saw a large green glob on the Weather Channel radar moving north from Atlantic City, but a little rain never stopped John Lennon* and it didn’t stop 30 Forgotten fans. And aside from a little drizzle, the green glob turned left at Newark.

*it’s supposed to link to “Rain” but it won’t.

The Battery Maritime Building at South and Whitehall (Municipal Ferry Terminal) serves ferries leaving for Governors Island. It was built from 1906 to 1909 and recently enjoyed a multimillion $$ restoration. There was also ferry service to Brooklyn from here until 1938. Photos: Eric Weaver.

Forgotten fans gather outside the rebuilding ferry terminal. The Staten Island Ferry is receiving two new ferry terminal buildings on each end of the trip, and approval has just gone through to lengthen the platforms on the IRT South Ferry station. Its connection to the Lexington Avenue line may be restored as well, and there may also be a transfer constructed to the BMT Whitehall Street station.

The IRT Lexington Avenue line reached Bowling Green in 1908 and subway architects George Heins and Christopher Lafarge constructed “control houses” here and elsewhere along the line. They were so called because they “controlled’ passenger entrance and exit with two dedicated doorways, which people obeyed(!). Photo: Leo Yau

New York Unearthed, at Pearl and State Streets, is run by South Street Seaport and is a repository for all manner of detritus from all the centuries of NYC’s existence (since the 1640s) raised from street excavations; the collection consists of small items like eating utensils, pipes and bottles, though there are several large items, like a Dutch cannon. The museum had over three quarter million items from the infamous Five Points slum stored in an underground office at the World Trade Center until 9/11/01. Only a couple of dozen that were out on loan survived.

The museum also occupies what used to be Herman Melville’s birthplace, 6 Pearl Street. Photo: Mike Epstein. LEFT: Your webmaster ponders Melville’s bust.

One of Manhattan’s oldest man-made artifacts still in its original spot is the iron fence at Bowling Green, built in the early 1770s. It originally featured crowns symbolizing British monarchy, but these were removed and according to legend, melted down and remade as ammunition. The fence was removed for renovation for five years between 1914 and 1919. It also acquired electric lamps somewhere along the way. Photo: Amy Langfield

Where it all begins. Broadway begins at Bowling Green and continues north, eventually as Route 9, almost to the Canadian border. #1 Broadway is the International Merchant Marine Company Building. Once, this was the booking hall for U.S. Steamship Lines, and nautical touches are found all over the exterior. Photo: Leo Yau

The huge Beaux-Arts pile facing Bowling Green is the old U.S. Customs House, a.k.a. The Alexander Hamilton Customs House, a.k.a. the Museum of the Ameerican Indian, built by Cass Gilbert beginning in 1899. Sculptures representing the 4 continents, as well as these cartouches, are found on and outside the building’s exterior. The building harks back to a time before the income tax (pre-1913) when the U.S. government got most of its scratch by slapping duties on incoming goods. This building was the nation’s largest collector of foreign duties. The Museum moved here from its old digs uptown in Audubon Terrace in 1994. Photos: Eric Weaver and Leo Yau

Beaver Street: though the city is installing “retro-crooks” all over town, it takes a trained eye to spot the McCoys, like this “Type 1 BC” which can be recognized by the castiron garland snaking around the shaft, as well as the crossbar ladder rest. Photos: Leo Yau, Amy Langfield

Neon legacy: A. Blank Office furniture sign at Broad and Stone Streets. Photo: Leo Yau

Samuel Fraunces’ Tavern, at Broad and Pearl Streets. The present structure dates to 1904 and is a replica of the tavern where Washington gave a fond farewell to his victorious troops in 1783. He would return to NYC 6 years later to take the oath of office as President. Fraunces was of West Indian descent. Photo: Leo Yau

Forgottoners check the underground remains of the Lovelace Tavern outside 85 Broad Street. Most of NYC’s downtown colonial architecture was lost in a horrendous December 16,1835 fire (a night when the temperature dropped below zero, hindering firefighting), but underground remnants, such as a tavern belonging to Francis Lovelace, New York’s second British governor, have remained. The tavern was discovered in 1980 during excavations for 85 Broad; archeologists had been hoping to find remains of the Staat Huys (State House), the old Dutch city hall, but this was the next best thing. Photo: Amy Langfield.

Stone Street (left) and Pearl Street between Broad Street and Coenties Alley each preserve buildings that went up in the post-1835 conflagration era. Photos: Leo Yau (l), Amy Langfield

Coenties Alley is now a pedestrian-only, faux-aged passage. According to legend it takes its name from Conraet Ten Eyck and his wife Antje, who owned the property where the alley stands now in the1600s. In English, their names would be Conrad and Ann Of The Oaks.

While Hanover Street and Square recall British royalty, Dutch NY governor and goldsmith Abraham DePeyster can be found in the square. His statue was brought here from Bowling Green in 1986. The square was where William Bradford set up the colonies’ first printing press in 1693. The big building ion the background is 7 Hanover Square, which was supposed to be reminiscent of Frank Lloyd Wright; I don’t see it, but…

Corner triangle buildings, like this one and the Flatiron Building, seem to be sailing down the street especially when viewed at a distance. Photo: Leo Yau

Lower Manhattan’s street pattern was built to conform to the curving shoreline. South William Street, on the left, was built parallel to Stone and Water, which was the waterfront at the time. Beaver Street comes in to meet it at right. Crazy-quilt intersections make for interesting architecure. Delmonico’s Restuarant, beloved by generations of Wall Streeters, moved into this space in 1891. The two columns in front were brought to the USA by the Delmonico Brothers from Pompeii and also stood at the restaurant’s previous location which burned in 1835. Photo: Leo Yau

The Canadian Imperial Bank of Commerce, originally the City Bank Farmers’ Trust Company (1930-31) has some fanciful metalwork and its giant limestone coins (below) are not to be missed. Photos: Amy Langfield (above left) Leo Yau (above right, lower left)

On September 16, 1920, person or persons unknown exploded a bomb in front of 23 Wall Street, then as now the offices of J.P. Morgan Inc., causing 400 injuries, some of them horrific, and 33 deaths. Morgan has never repaired the pockmarks in the building caused by the flying debris.

George Dubya, Washington, that is, watches over Forgottoners assembling for the now-traditional group photo. Washington took his oath of office as first US President at this spot at then-Federal Hall (the present structure dates to 1833); the US Capitol would remain in NYC until decamping to Philly in 1790. John Q. Adams’ statue was installed in 1883. Photo: Amy.

Another guy with Q as a middle initial

Your webmaster explains why there’s a plaque featuring the State of Ohio at Federal Hall:

The Ohio Company of Associates, a cadre of American Revolutionary officers led by Manasseh Cutler, most from New England, was formed to settle lands along the Ohio River in 1786, and soon afterwarrd the Northwest Ordinance of 1787 was passed by Congress in NYC (Congress was meeting here at the time) and led to the settlement of nearly 2 million acres in what would become the state of Ohio in 1803. The Ordinance provided a temporary government for the territory with the provision that, as soon as the population was sufficient, the representative system should be adopted and later that states should be formed and admitted into the Union. The Ohio Company formed Marietta in 1788, Ohio’s oldest permanant settlement.

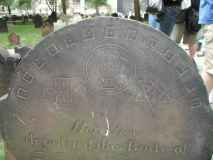

Tales from the cryptic: Trinity Church dates to the mid-1840s, but its burying-ground dates to the earliest Dutch colonial days in the mid-1600s. One of the more intriguing stones is that of James Leeson, who died in 1792. For decades, the box-and-dot code at the top of the stone remained a mystery, but as Meyer Berger explained in his NY Times column in the 1950s, experts finally figured it out. It says…

“Remember death”

Other cryptic Masonic symbols are also on the stone. Also note the “long s” on the stone in Leeson. S’s occurring in the middle of words were written like this until about 1800.

[image missing]

Barthman’s Jewelers’ clock has been embedded in the sidewalk at Broadway and Maiden Lane since 1899. It has been attacked by vandals, been walked on and suffered the risk of canine ejecta for years but it keeps on ticking (with the help of an electric motor.)

As far as I know, it is the only clock embedded in a sidewalk in the USA, athough there is another in London. Photo: Amy

It can’t be proven but this building on Nassau Street between Maiden and John may have been James Bogardus‘ first cast-iron building front. Most are further uptown in Soho. Note the two Ben Franklin bas-reliefs: two of washington have been mysteriously removed. Photo: Amy.

Fulton Street is a fascinating repository of architecture styles past and present. 1930s utilitarian (concrete ‘subway’ sign), 1890s Beaux Arts with odd modular 1970s crap, complete with old ‘facsimile’ and ‘typewriter’ signs. Remember typewriters? These buildings are endangered by a new ‘transit hub’ to be erected by the late 2000s. Photos: Amy.

The 1893 Keuffel & Esser Building at 127 Fulton housed the 20th Century’s leading manufacturer of slide rules, another outdated technology. Note the sculpted drafting instruments. K&E had a much bigger building in Hoboken. Photos: Leo.

Gold Street is another of lower Manhattan’s incredibly narrow ways, and off Fulton Street are two hidden treasures, the 1888 Excelsior Power Company Building, with its fancifully lettered sign, and Edens Alley, which recently had its old name restored after 157 years. Photos: Amy.

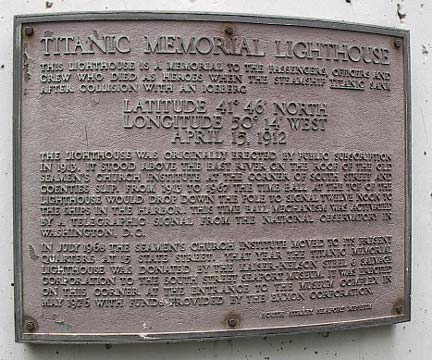

The Titanic Memorial Lighthouse stands at Water and Fulton was moved to the Seaport in 1968 after urban renewal displaced it from its old spot on the Seamen’s Church Institute at South Street and Coenties Slip. It was built in 1915 as a tribute to those who died in the Titanic disaster in April 1912. Photo: Eric Weaver

The Second Shearith Israel Cemetery, St. James Place near Chatham Square. It is NYC’s oldest extant cemetery. From sephardicstudies.org:

Shearith Israel was the only Jewish congregation in New York City from 1654 until 1825. During this entire span of history, all of the Jews of New York belonged to the congregation. Shearith Israel was founded by 23 Jews, mostly of Spanish and Portuguese origin. The earliest Jewish cemetery in the U.S. was recorded in 1656 in New Amsterdam where authorities granted the Shearith Israel Congregation “a little hook of land situated outside of this city for a burial place.” Its exact location is now unknown. The Congregation’s “second” cemetery, which is today known as the FIRST cemetery because it is the oldest surviving one, was purchased in 1683.

The other two Shearith Israel Cemeteries are on West 11th Street east of 6th Avenue and West 21st Street, west of 6th. Photo: Eric Weaver

First there is a Bowery, then there is no Bowery, then there is. Chiseled sign at St. James Place and Madison Street shows a former name. The road, part of the Post Road going to Boston, was also called New Bowery for a few decades. Photo: Leo

From the 1820s through the 1840s, Five Points, the intersection formed by Anthony (Worth) Orange (Baxter) and Cross (Mosco) Streets, was a horribly squalid slum featuring nearly inhuman living conditions, giving rise to vicious gangs such as the Dead Rabbits and Bowery Boys, as recounted in Herbert Asbury’s book and later, Martin Scorsese’s film Gangs of New York. At left is a lithograph of Five points and the Old Brewery building; at right is the Old Brewery site today at Columbus Park. Photo right: Amy.

I discussed Five Points on my Lower Manhattan Street Necrology page:

From Kenneth Dunshee’s 1952 account in “As You Pass By”:

The Old Brewery was a five-story building, old and dilapidated. Along one wall an alley led to a single large room in which more than seventy-five men and women of assorted nationalities and races lived together. This was the Den Of Thieves. The name was appropriate. Along the other wall ran another filthy lane called Murderer’s Alley worse than the first.

Upstairs there were about 75 other chambers, housing more than 1,000 people…men, women and children. The section was a warren, with underground passages and murderous cul-de-sacs, into which the police dared venture only in large numbers, for the Old Brewery for a period of more than fifteen years averaged a murder a night.

Five Points was too tough, too unlawful, too unsavory to last, even in the New York of a century ago. The Old Brewery was razed, the last of the gangs destroyed. Today it bears little resemblace to the bull-baiting, rip-roaring hell it was in 1850.

And from Charles Dickens in America: Notes For General Circulation (1842):

What place is this, to which the squalid street conducts us? A kind of square of leprous houses, some of which are attainable only by crazy wooden stairs without. What lies behind this tottering flight of steps? Let us go on again, and plunge into the Five Points. This is the place; these narrow ways diverging to the right and left, and reeking everywhere with dirt and filth. Such lives as are led here, bear the same fruit as elsewhere. The coarse and bloated faces at the doors have counterparts at home and all the world over. Debauchery has made the very houses prematurely old. See how the rotten beams are tumbling down, and how the patched and broken windows seem to scowl dimly, like eyes that have been hurt in drunken forays. Many of these pigs live here. Do they ever wonder why their masters walk upright instead of going on all fours, and why they talk instead of grunting?

—————————————————

By the 1920s, most of the vestiges of the old Five Points had been replaced by court houses, and by the 60s, high rise apartments had obliterated the last of its little wood frame and brick buildings; Columbus Park stands on its old intersection. It’s a shame, though, that some of the buildings of this notorious slum couldn’t have been preserved in some way.

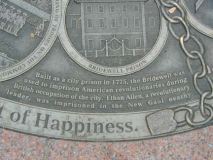

Forgottoners, tired after 3 hours of marching, elected to end things shortly after passing Five Points, but the more indefatigable of us pressed on to Foley Square, where we saw a relatively new instalation in the sidewalk recounting the history of the place; among other things, there was a large freshwater pond nearby called Collect Pond (and another one uptown named Sunfish Pond). After decades of NYers depositing garbage and offal into the pond, it was decided to drain it into the Hudson River. The duct is still there, in a sewer under Canal Street. This is really worth a visit…it includes a detailed 1820s street map of the area!

Photo: Eric Weaver

Sugar refineries, called sugar houses, were built in lower Manhattan during the mid to late 1700s to alleviate the need to import refined sugar from Europe. The sugar houses, with their small windows and low ceilings, were considered ideal by the British as prisons, and as on the prison ships in Wallabout Bay, conditions were notoriously inhumane, and may patriots died in captivity.

This sugar house stood at what is now Avenue of the Finest and Madison Street; its window was later incorporated in the Rhinelander Building, itself torn down in 1968. The window now stands in the pedestrian plaza behind the Municipal Building.

As many as 800 Americans were crammed in a typical sugar house,

suffering a tremendous amount of abuse and left with the choice of either starving or freezing to death. Conditions were so bad that many inmates carved messages and their names on the beams and walls. For years afterward these ‘last wills’ remained.

–Kenneth Dunshee in As You Pass By

According to sources such as Richard McDermott of The New York Chronicle and Steve Redlauer and Ellen Williams of “The Historic Shops & Restaurants of New York”, the Bridge Cafe, at Water and Dover Streets, is the oldest establishment in NYC that has continuously been run as a tavern. In a number of different guises and many different owners, it has been here, in this building since 1794.

It was built on the water’s edge, as Water Street marked the original shoreline. The Brooklyn Bridge behind it went up in 1883. It was originally listed as a “grocery and wine and porter bottler”; in that era, groceries sold wines and spirits and were issued liquor licenses. It doubled as a brothel in the 1870s when it was run by Tom Norton. It has been known as the Bridge Cafe since 1979.

And that’s -30- for another Forgotten Tour…

1 comment

[…] the road maintained some of its historical integrity–some of the underground remains of the Lovelace Tavern can be viewed through glass onsite at the Goldman Sachs […]

Comments are closed.