Known to most as a throwaway line in a Paul Simon song, or where you go for the Lemon Ice King, Corona, the neighborhood between Elmhurst /Jackson Heights and Flushing Meadows Park, has a well-defined history, as FNY correspondent Christina W. will relate…

GOOGLE MAP: CORONA

Above: sign, 37th Avenue

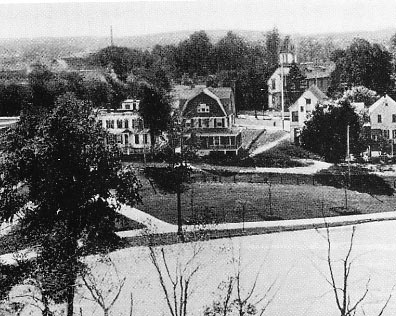

Before the land between Elmhurst and Flushingwas developed in the 1850’s, there were only a dozen families living in the area. From the highest point on a hill 108 feet above sea level, they could take in fantastic views of Long Island Sound and the isle of Manhattan and could even see clear to the Palisades of New Jersey. At the lowest point at Flushing Creek, they would bring their corn and wheat to be ground into flour at a grist mill. Farms here also grew cauliflower, broccoli, cabbage, kale, pumpkins, pears, peaches, apples and grapes, and raised pigs and cows. Hunting for cottontail and grouse, and setting traps in Flushing Bay for tasty tomcods were also ways the settlers varied the food served on their tables.

Before the land between Elmhurst and Flushingwas developed in the 1850’s, there were only a dozen families living in the area. From the highest point on a hill 108 feet above sea level, they could take in fantastic views of Long Island Sound and the isle of Manhattan and could even see clear to the Palisades of New Jersey. At the lowest point at Flushing Creek, they would bring their corn and wheat to be ground into flour at a grist mill. Farms here also grew cauliflower, broccoli, cabbage, kale, pumpkins, pears, peaches, apples and grapes, and raised pigs and cows. Hunting for cottontail and grouse, and setting traps in Flushing Bay for tasty tomcods were also ways the settlers varied the food served on their tables.

Ground was broken for the Flushing Railroad in 1853. This event would spark the transformation of the sleepy settlement into a bustling commercial, industrial and residential center. A real estate company was organized in Manhattan to create “West Flushing,” a name which wouldn’t last long. The West Flushing Land Company engineered the first of two major phases of development by selling houses on small plots carved out of former farmland.

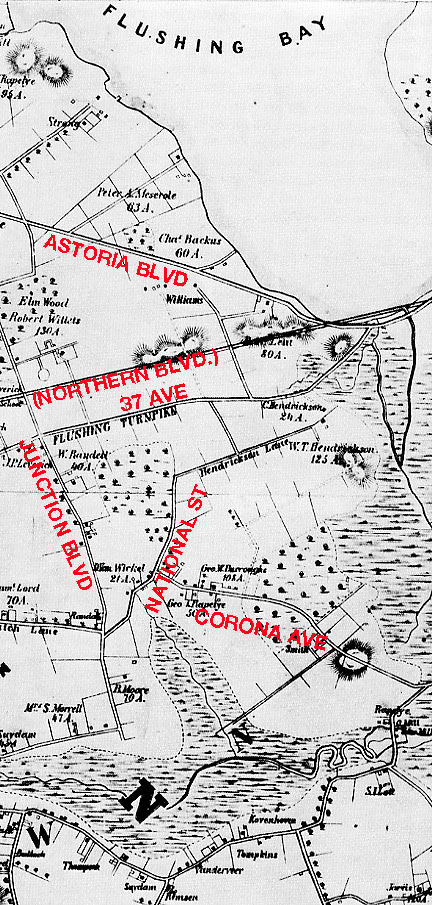

LEFT: 1853 map of Corona, before the railroad arrived. Modern street and road names are marked in red.

The twelve families in the area used only five roads to get where they needed to go. These were Junction Avenue (Boulevard, today), Newtown Avenue or Spring Hill Road (Corona Avenue, today), Grand Avenue (National Street, today), Shell Road (37th Avenue, today) and Hendrickson’s Lane (totally gone from maps since the mid-1800’s). Strong’s Causeway, which was a bridged passage over Flushing Creek, was absorbed into the Long Island Expressway.

(LEFT: Strong’s Causeway crossing the Flushing River in 1905)

National Racetrack clubhouse, 1850s

In 1854, the National Racing Association, a group of Southern horse owners, purchased a farm and erected a track to which they sent their racing horses to compete. On June 26, 1854, the first race was run at the National Racetrack, coinciding with the official opening of the main line of the Flushing Railroad, which created a stop for the track. In 1856, the track opened for the season as the “Fashion Pleasure Ground,” named after the champion horse, Fashion. In 1858, the track hosted the first baseball game for which an admission fee was charged. In 1861, the owners transported their horses back down South to help the Confederacy during the Civil War, so northern horses took their place. In 1867, the racehorse, Dexter, broke the world’s trotting record for the 1-mile course at the Corona track. Ulysses S. Grant attended a race there shortly after becoming President-elect in 1868. In 1869, the track hosted its last race and in 1871, railroad tracks for the Woodside Branch of the Flushing Railroad were laid through it, with a station called Grinnell located right in the center of the racing oval. The track structure and railroad stations are completely gone today; the only remnant of the racetrack is National Street, the route that ran past the park’s entrance.

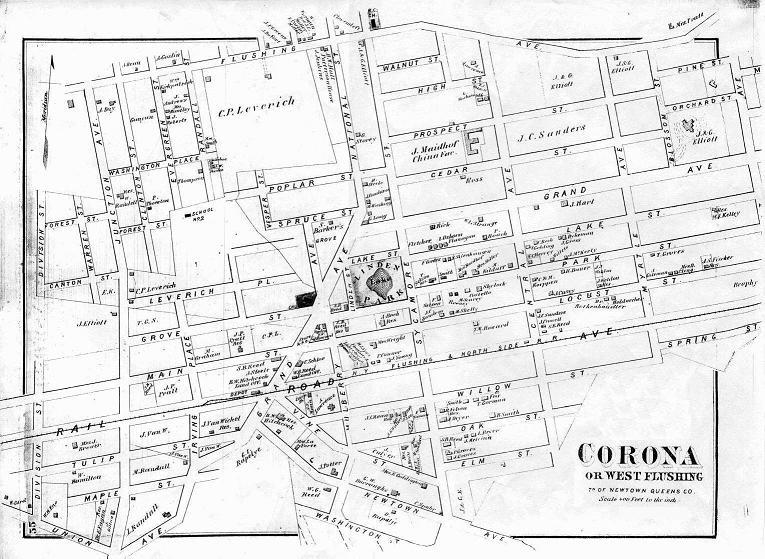

1873 Beers map of Corona. Though most of these streets are on the present-day map, only two have kept their names: Junction Avenue (Boulevard) and Spruce Street. map from Brooklyn Genealogy Information page

West Flushing’s second phase of development was the responsibility of Benjamin Hitchcock, who also developedWoodside at the same time. He bought 1,200 West Flushing lots in 1867 and sold them in 1870. He offered installment payments to his less wealthy customers, which was a novel idea at the time, and one which they found very attractive.

Resident Thomas Waite Howard discovered that his town’s name was confusing to outsiders and even to the post office. In 1868, he petitioned the post office to change West Flushing’s name to ‘Corona’ as he felt that his neighborhood was the “crown jewel” of Long Island. The post office granted his request in 1872.

In 1907, Michael Degnon, builder of the Williamsburgh Bridge, the Cape Cod Canal, part of the IRT subway and the Steinway Tunnels, and owner of the Degnon Terminal in Sunnyside, began buying up every tract of salt meadow along Flushing Creek. He thought that he would be able to build a port facing Flushing Bay, and that the federal government would pay for his plan to dig out the Creek from the Bay down to its headwaters at Kew Gardens to make it passable for large ships. He began buying ashes and refuse and dumping these onto the salt meadows to lay a foundation. Unfortunately all this did for Corona was to make the town stink like garbage. When residents looked east, all they saw were ugly gray mounds on the horizon. F. Scott Fitzgerald immortalized this ‘valley of ashes‘ in The Great Gatsby.

The feds initially approved of the plan, and dredged part of the creek near its mouth. However, in 1917, the government’s focus turned to WWI and the port plan was abandoned. The dumps remained an eyesore until 1937, when Robert Moses cleaned them up in anticipation of the 1939-1940 World’s Fair at what would later be known as Flushing Meadows–Corona Park. The site was used again for the 1964-1965 World’s Fair, remnants of which are featured on FNY’s No Fair At All page.

After WWII, most Corona residents could trace their roots back to Italy, Germany, Ireland, or other parts of Europe. By the 1970’s, a new wave of immigrants of Hispanic and Asian origin had discovered the area and moved into the community in large numbers. These constitute the predominant ethnic groups living in Corona today. Paul Simon, who grew up in neighboring Forest Hills, alluded to the transition in one of his popular 1972 songs:

“Goodbye Rosie, Queen of Corona. See you, me and Julio down by the schoolyard.”

Redevelopment of this neighborhood has been slower than in surrounding areas of Queens, leaving some relics of Corona’s past untouched for more than a century.

According to NYC’s Landmark Preservation Commission, “This small two-story house (c. 1871) is one of the last intact 19th century frame houses in Queens. Designed in a vernacular Italianate style, the house is notable for its decorative porch, gable and fence.” The house is on 47th Avenue between 102nd and 104th Streets and was home to poet, essayist and political writer, Edward E. Sanford (1805-1876). He was the son of U.S. Senator Nathan Sanford (1777 – 1838), who owned most of the land in the Waldheim section of Flushing, which is described on FNY’s Flushing Remnants page. Sanford Avenue in Flushing is named after the family.

National Street

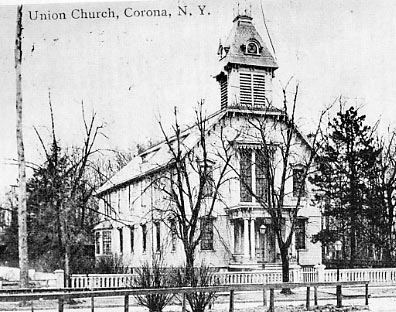

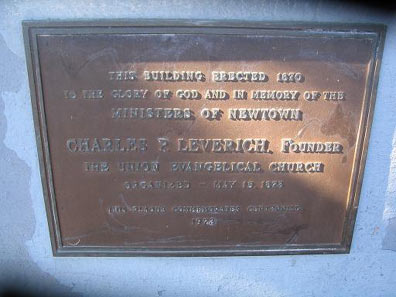

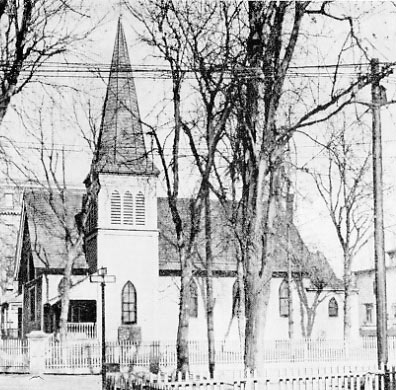

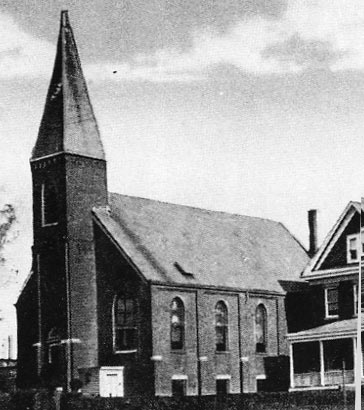

The Union Evangelical Church at National and 102nd Streets was built in 1870 and was the first church in Corona. The land for the church was donated by Charles Leverich, a wealthy area landowner, who also became instrumental in the church’s success.

Maurice Connolly (1881-1935) was Queens Borough President from 1911-1928, and made his home in Corona for part of that time. His house, pictured above, left, had to be moved for construction, and now sits behind the Union Church on 42nd Avenue. Connolly was the youngest and longest serving Queens borough president but fell from power due to a major sewer scandal.

1927: Connolly urges Queens businesses to adopt new street numbering system

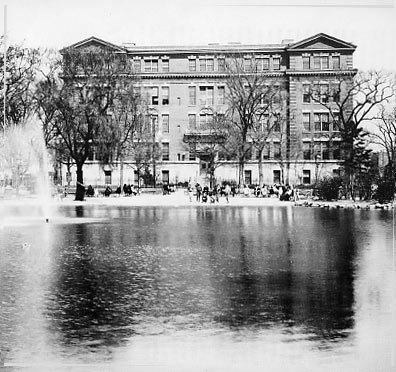

In the picture at right the Connolly house is shown in its original position at Linden Park in the early 1900s. At the time the park contained a large pond, Linden Lake (about which q.v. below).

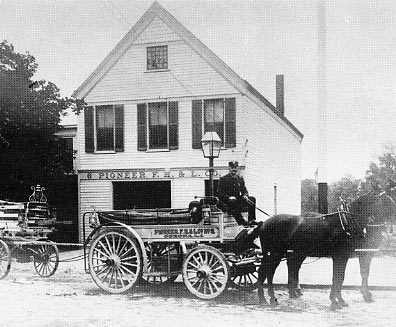

In 1913, the city of New York took over firefighting services in Corona and built a modern firehouse on 43rd Avenue in 1914. The Pioneer Hook and Ladder Company (above, left), the all-volunteer force that had fought Corona’s fires since 1890, was then disbanded. Their firehouse, however, continues on across the street from the Union Church, hidden in plain sight in the form of a gift shop.

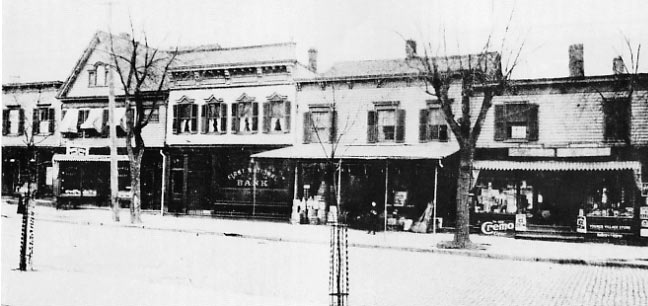

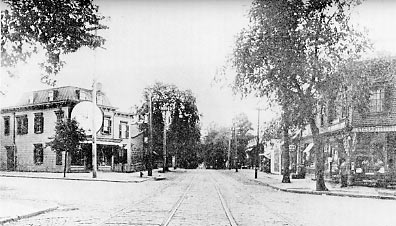

With the railroad station located within walking distance, National Street was the center of town from 1854 to about 1915. The signs out front and the goods inside this strip of stores may have changed over time, but the buildings themselves haven’t been altered much. Photo beneath from 1900.

Site of the Corona rail station is seen in present-day photos at FNY’s Pride In Port, Part 1.

A Mystery

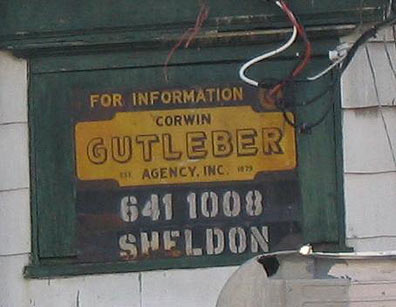

The National Street building with the peaked roof features a sign on the right side of the building in both the 1900 photo and the present-day. The sign, seen at left, is for the Corwin-Gutleber Agency, est. 1879; apparently, only Gutleber is in business these days.

In any case, the sign probably doesn’t date to 1900 but could very well go back to the 30s or 40s.

This building at the corner of 43rd Avenue and National Street has been standing since the late 19th century. The New York and Queens County Railway used to run trolleys along the avenue in front of it. The trolley’s path became the Q23 bus route.

[It’s indistinct but if that circular structure is a clock it’s half the size of the building! –your webmaster]

Linden Lake

These youngsters above are enjoying their recently refurbished ballfield at Linden Park. This site has always been a park, but had the kids been standing in this spot prior to 1947, they’d find themselves waist-deep in water. Linden Lake, seen on the 1873 map pictured previously (and pictured above, right, circa 1930 at P.S. 16), was deemed a health and sanitation concern after WWII. Prior to it becoming polluted and filled in, the lake served as an oasis for the community.

More Houses of Worship

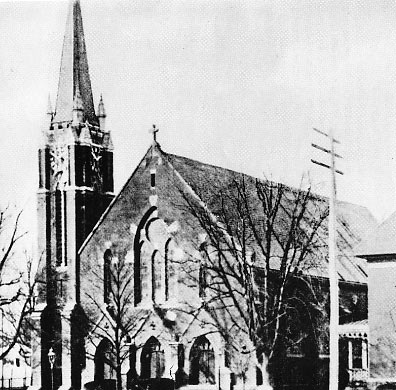

Our Lady of Sorrows was the first Roman Catholic Church to minister to Corona. It opened in 1872. The original wooden structure was replaced with this brick one in 1900. The church is on 37th Avenue at 104th Street.

Methodist Episcopal Church was founded in 1887 (above, left). Original structure has survived, minus the steeple (above, right).

The Emanuel German Lutheran Church was founded in 1887. The new church is pictured above soon after its opening in 1902 (left) and in 2005 (right). Today’s services are performed in Korean and Spanish rather than in German.

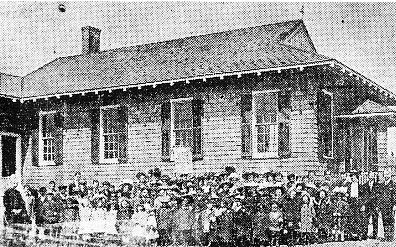

Grace Episcopal Church was founded in 1906 (seen at left as Sunday school was letting out); this parish hall on 98th Street was built as a chapel in 1907. The modern church can be seen here.

Shaw AME Zion Church, on 34th Avenue, has been in existence since 1957. Prior to then, it housed the North Side Hebrew Congregation, which dated back to the early 1900’s.

Congregation Tifereth Israel of Corona, also known as the Home Street Synagogue, was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2002. It was founded in 1911 on what is today 54th Avenue. Tifereth means “Glory of God.”

Before she was known as Estée Lauder, Josephine Esther Mentzer attended this synagogue while growing up above her father’s hardware store on nearby Hillside Avenue (Van Doren Street, today). In a stable behind the house, her uncle, a chemist, mixed experimental face creams which Estée sold in Manhattan beauty salons. Over time, Estée managed to develop her one-woman cosmetics enterprise into a multi-billion dollar empire.

Before she was known as Estée Lauder, Josephine Esther Mentzer attended this synagogue while growing up above her father’s hardware store on nearby Hillside Avenue (Van Doren Street, today). In a stable behind the house, her uncle, a chemist, mixed experimental face creams which Estée sold in Manhattan beauty salons. Over time, Estée managed to develop her one-woman cosmetics enterprise into a multi-billion dollar empire.

Tiffany Glass Works

In 1893, Louis Comfort Tiffany and his business partner, Arthur Nash, founded the Stourbridge Glass Company in Corona next to the railroad tracks. In 1902, the name of the enterprise was changed to Tiffany Furnaces. His patented “favrile” (handmade) glass was created and manufactured here. Tiffany’s works reached the height of their popularity in the years leading up to WWI and the pieces are now much sought after works of art. Business slowly declined after the war, as tastes had changed with the passage of time. In 1928, Tiffany withdrew from the company, leaving Nash’s son to run the business alone under a different name. The Great Depression brought about the end of the company. However, the factory and furnace buildings on 97th Place remain standing* and are actively used today. The Queens Museum, located in nearby Flushing Meadows-Corona Park, has a permanent Tiffany collection on display, as does the Metropolitan Museum of Art in Manhattan.

*The Tiffany glass works was razed in 2013 and a public school built in its place. Glass fragments found at the site were fashioned into an art installation installed in the school.

Corona’s Theatres

The Hyperion Theatre, above, left, opened in 1910 on National Street (now 103rd). Today, the same location at 103rd and 39th Avenue is a pizza place, with offices occupying the upper floor.

[Model T’s to SUV’s! –your webmaster. Yeah, I know they’re not Model T’s. But it rhymes.]

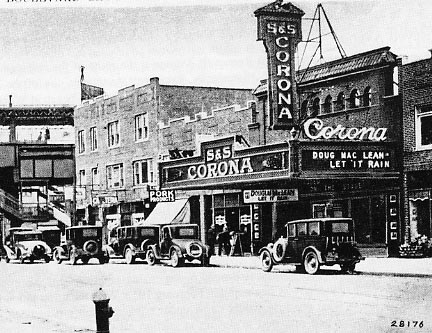

The Corona Theatre was located on Junction Boulevard just north of the Roosevelt Avenue el. [The theater opened in 1927 and survives today as a row of stores on Corona’s busiest retail strip. Let It Rain came out in 1927; it featured one of Boris Karloff‘s first screen appearances–your webmaster]

The Plaza at 103rd Street and Roosevelt Avenue is the only theater left in Corona. It was owned by Loew’s until 1952, when it became an independent movie house. Today, the auditorium floor is occupied by a Walgreen’s and other stores and only the balcony is used for showing films either in Spanish or with Spanish subtitles. A photo of the theater in its heyday can be seen here.

TOP: El Vacilon with Luis Jimenez and Moonshadow Broussard of La Mega, the Latino Opie and Anthony.

BOTTOM: your webmaster shot the Plaza in its last days with English language films in 2002 when Spider-Man Iand J-Lo’s flop of the moment, Enough, was playing.

Trainspotting

[The above shows the Junction Boulevard elevated station under construction in 1915. From the beginning, a third track was constructed to enable express service during rush hours, but the lack of a 4th track makes round-the clock express service impossible.

The origin of the name of Junction Boulevard remains a mystery, but my guess is that the road led to a confluence of other paths or perhaps horsecar lines. Roosevelt Avenue was constructed along with the elevated, and opened for traffic in 1919.–your webmaster]

A trolley line was built from Brooklyn to Flushing during 1893-1894; its route spanned the entirety of Corona Avenue. In 1917, the elevated IRT Flushing line, today’s #7 train, was completed as far east as 104th Street (then called Alburtis Avenue). People no longer relied on the railroad for transportation, as the subway and trolley were less expensive. This gave rise to two main commercial drags: Roosevelt Avenue, under the el, and Corona Avenue, along what is presently the path of the Q58 bus line. The Bridge and Tunnel Club has a nice set of shots of Roosevelt Avenue, in a predominently Hispanic section of the neighborhood. The following scenes can be found along Corona Avenue, which runs through the heart of an Italian enclave. Both collections of photos shed some light on the community’s more recent past as well as its present.

Now That’s Italian!

A 108th Street mainstay, Peter Benfaremo’s Lemon Ice King of Corona started dispensing lemon-flavored Italian ice in 1944. Today, the establishment serves either 25 or 29 varieties (depending on which of their signs you believe). Famous for their ices containing chunks of real fruit, their selection today also includes exotic flavors such as chocolate chip and peanut butter.

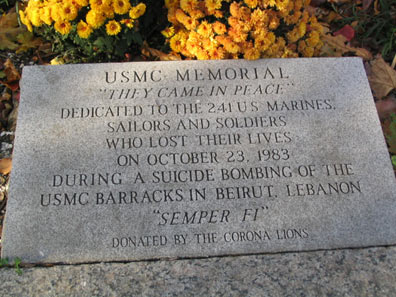

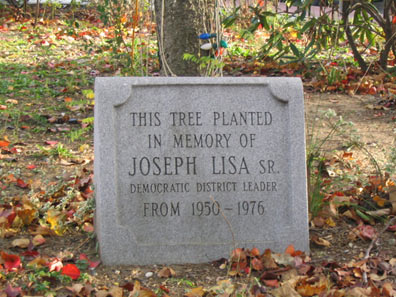

Memorials, birdhouses and bocce

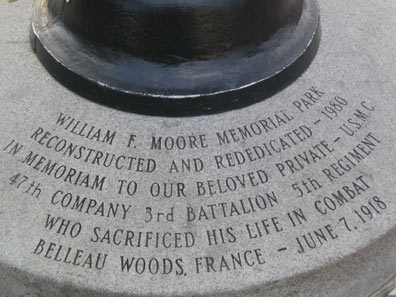

During the summer, many enjoy their ice while watching bocce games in what locals refer to as “Spaghetti Park.” The moniker pays homage to the Italians who remain a small but tight-knit part of the community. The official name of this park is William F. Moore Memorial Park, named after a local resident who lost his life in WWI. Before being dedicated to Moore’s memory, the park had been named the Corona Heights Triangle. Memorials of all kinds have been placed in the park over the years, signifying just how important the intersection of 108th Street and Corona Avenue is to the community.

The park itself is the site of some forgotten history – the Victory Memorial Fountain, aka the Corona Heights War Memorial, by sculptor James Novelli, was installed here in 1927. A description of the memorial can be found in a biography of the artist, Novelli: A Forgotten Sculptor, by author Josephine Murphy – “The fountain consisted of a large circular granite water basin in the center of which stood a ten-foot high cylindrical granite monument supporting bronze panels which were separated by Doric columns.” The bronze panels listed the names of the sons of Corona lost in WWI. Unfortunately, the fountain fell victim to decay and vandalism over the years, and a decision was made to remove it rather than restore it when the park was redesigned.

Salumeria: A store that sells cold cuts, including salami, prosciutto, and other sliced meats. (left)

An old fire pull station repainted in the colors of the Italian flag. (right)

Many of Corona artist Richard J. Finnell’s “Queens Scenes” feature sights along Corona Avenue.

Filmmaker Martin Scorsese is a Corona native. He has been quoted as saying: “I was born in the peace and greenery of Corona, Queens in 1942. And I loved it. I loved Corona, Queens. It was two-family houses. There was a little yard in the back, a little tree.”

Beloved NCAA basketball coach and commentator Jimmy Valvano also grew up in Corona.

Lefrak City

After WWII, affordable housing in Queens was in high demand. The Lefrak Organization stepped up to the plate in 1960 and built a huge complex in the southernmost reaches of Corona, just north of the Long Island Expressway and east of Junction Boulevard. Five thousand apartments make up this “city within a city.” The top of the complex’s office building can be seen for miles.

The Jazzmen of Corona

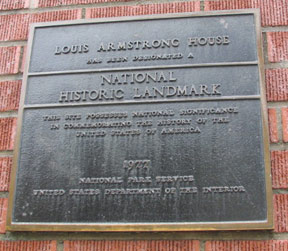

Music legend Louis Armstrong moved into working-class Corona in 1943. He had spent so much time on the road that he never owned a house until his wife, Lucille, found this one. He lived the last three decades of his life here and died here in 1971. His final resting place is in Flushing Cemetery. Satchmo’s house on 107th Street is now a museum. Daily tours are offered of his modest yet fascinating home. Here are some sneak peeks of Pops’ living room and his kitchen.

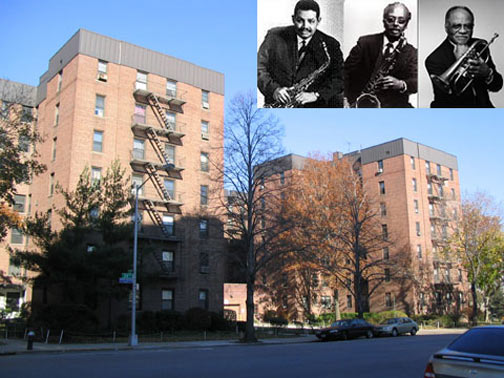

Armstrong participated in frequent jam sessions with his friend and neighbor, trumpet legend Dizzy Gillespie, who lived around the corner on 37th Avenue (above, left) from 1952-1966. Dizzy passed away in 1993 and his grave is also in Flushing Cemetery, however, his family’s plot is unmarked.

The Dorie Miller Houses co-op (above, right) is where saxophonists Cannonball Adderly and Jimmy Heath and trumpetistClark Terry resided; Heath still lives there. The street is also named after Pearl Harbor and WWII hero Dorie Miller.

Pianist Cecil Taylor was born in Corona, and the title of one of his more recent albums contains the town’s name.

More Jazzmen (and women) of Queens

Coda

Your webmaster here. Before we leave Corona I thought I’d stick in my two cents, from a walk I did here in the summer of 2005…

This Victorian-era relic on 37th Avenue and 104th, across the street from Our Lady of Sorrows (see above) was sacrificed in 2005 to the clutches of greedy development, which moved swiftly to erect multi-family dwelings. Much more stringent landmarking and preservation laws are necessary to stop the demolition of our heritage. Increasingly, this is the face Corona presents to the world:

37th Avenue. The one on the left is almost presentable, but the one on the right is drab, functional, and almost prison-like.

We get the architecture we deserve, said a NYTimes editorial when Penn Station came down. Perhaps, this is all we deserve…

Special thanks to: Charles Witek of the Coastal Conservation Association of New York, Judith Ackerman, Antonette Ancona, and Kevin Burgess for their assistance with this page.

SOURCES:

Corona: From Farmland to City Suburb (1650-1935) aka The Story of Corona (Queens Community Series), Vincent Seyfried, Edgian Press, Inc. 1986

[available from Greater Astoria Historical Society]

all pictures of old Corona on this page are from this book

Novelli: A Forgotten Sculptor, Josephine Murphy, Branden Publishing Company, 2003

BUY this book at Amazon.COM

All About Jazz

Cinema Treasures

National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum

New York Newsday

New York Times

Orthodox Research Institute

Queens Chronicle

Queens Tribune

Special Broadcasting Service

V Foundation

These photos were taken on November 13th, 20th and 28th, 2005, and this page was completed on snowy December 4th, 2005, by Forgotten NY correspondent, Christina Wilkinson.

4 comments

[…] Corona Crown of Queens – Kevin Walsh […]

[…] on the site of the former Tiffany Glassworks building in Corona, Queens. Scroll down some… https://forgotten-ny.com/2005/12/corona-crown-of-queens Looks to be that giant red brick warehouse building. SOM told me that they’ve made provisions […]

[…] examples of reputed works executed by Louis Comfort Tiffany in his Queens studio located in Corona from 1893 to 1924. Over the altar (not shown on these exterior shots) is the triptych window […]

[…] 21 years after this article was published, a group of residents from Corona, Queens, got together in December 1911 to devise a way to get rich off of stray cats. Recognizing that cat […]

Comments are closed.